Table of Contents

Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR)

Presentation Slides

What is ASMR?

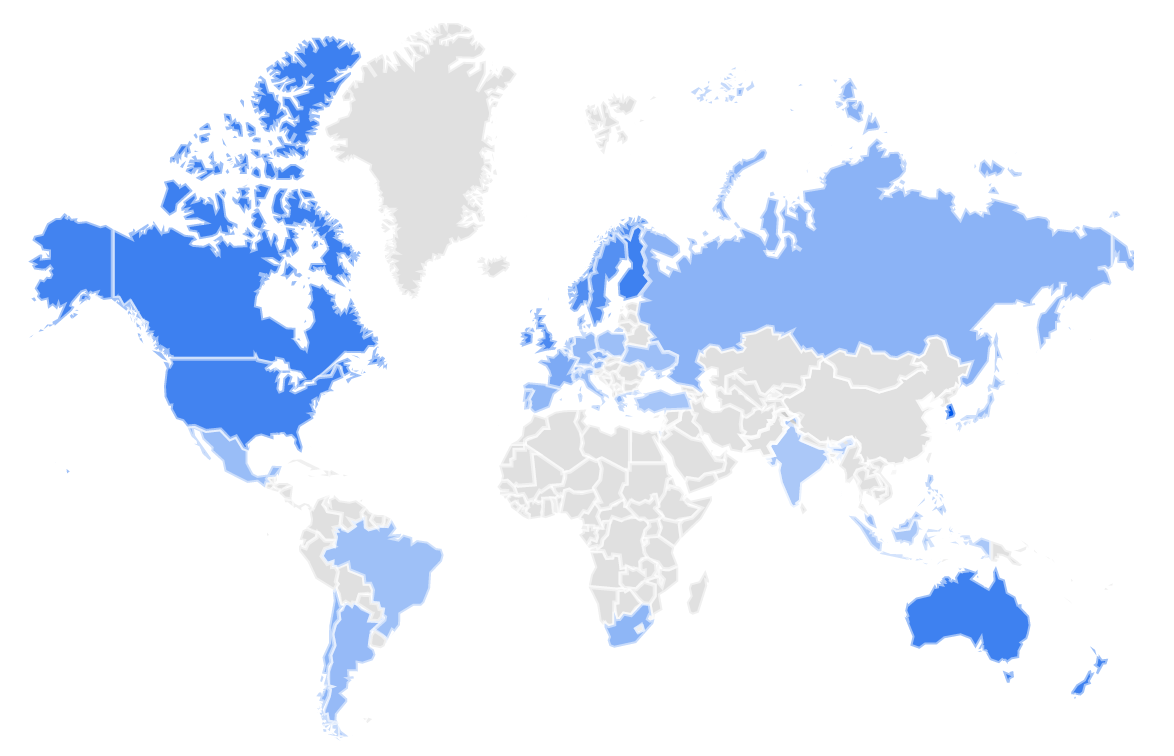

ASMR stands for autonomous sensory meridian response. People around the world usually know it as the tingles, brain tingles or brain orgasms in response to sensory stimuli (Sciencedaily, 2018). Many people are under the impression that ASMR is a type of video. Yet, autonomous sensory meridian response is a type of response from watching certain videos or hearing certain sounds resulting in feelings of euphoric tingling and relaxation (What is ASMR?, n.d). These videos can be about incredibly simple, quiet and calming tasks like folding towels, brushing their teeth, flipping magazine pages (What is ASMR?, n.d).

However, autonomous sensory meridian response is not the same as sexual arousal. Autonomous sensory meridian response is not the regular kind of orgasm that occurs in the brain due to peripheral manifestations (The ASMR, n.d.). Its responses are triggered by a variety of very odd sensations (The ASMR, n.d.). Interestingly, 5% of the male participants said that they watch ASMR media for sexual relaxation (Etchells, 2016).

ASMR doesn’t seem to work for everyone in the population. It can be tough to imagine the sensation if you don’t experience it first-hand (The ASMR, n.d). For the population that does experience ASMR, they get a blissful tingling starting up in the scalp and the making its way through the body (The ASMR, n.d). The public interest in ASMR has risen dramatically over the past couple of years. This also resulted in what they called themselves practicing “ASMRtists” to promote relaxation and sleep (Poerio et al.,2018).

Physiology of ASMR

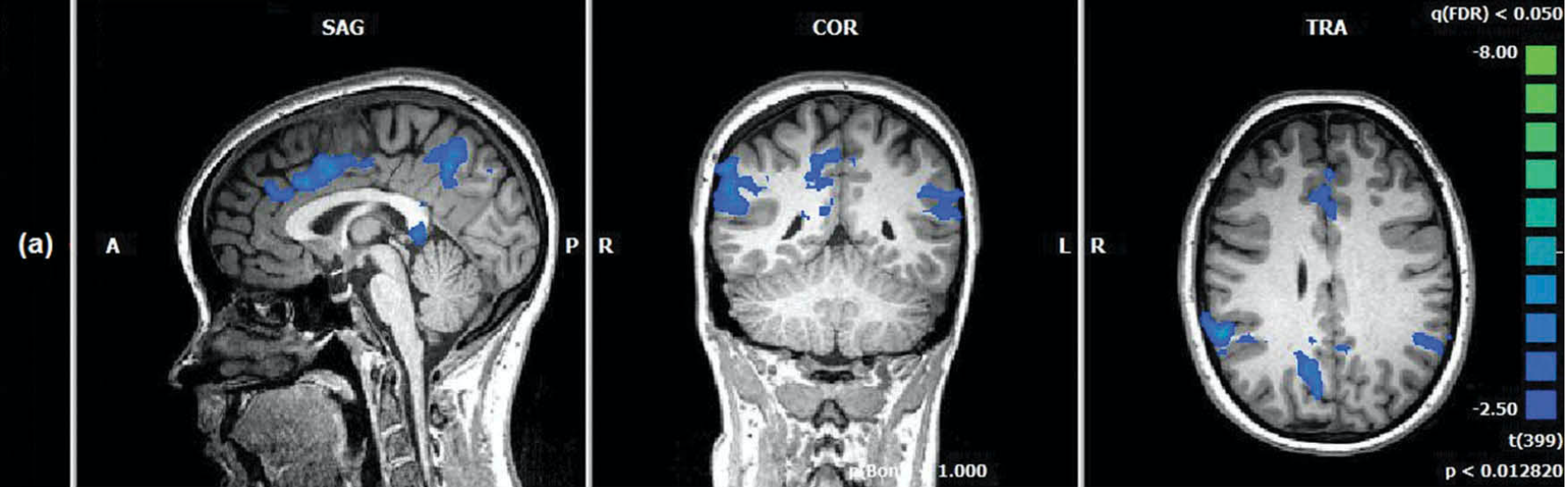

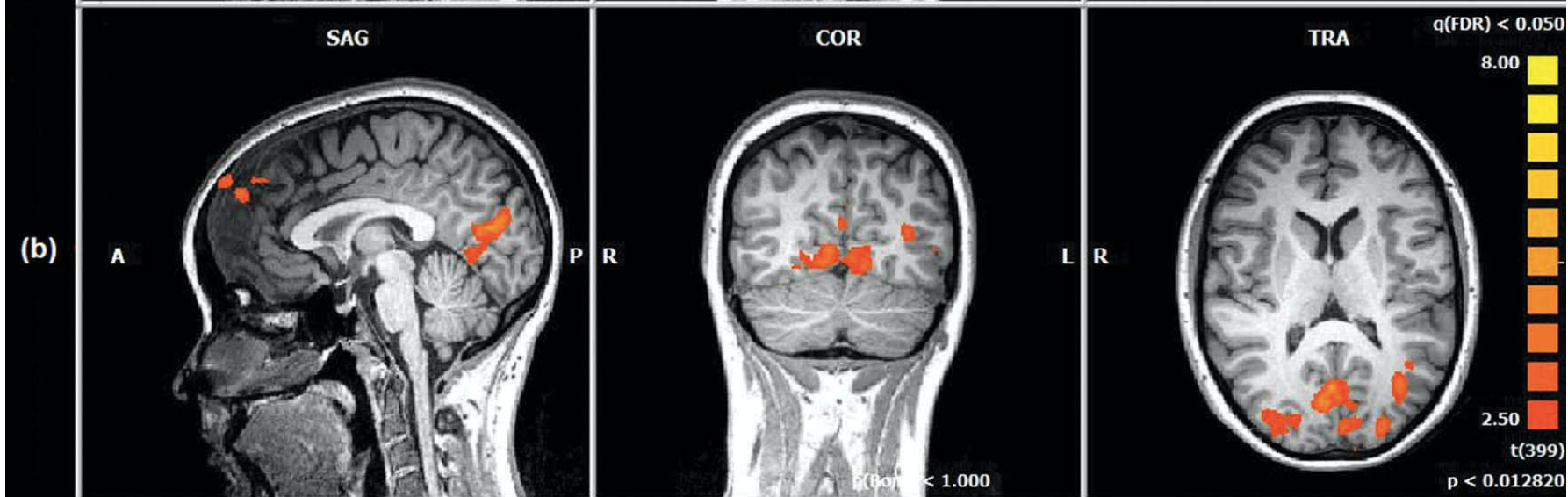

Evidence shows that Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response is a very complex phenomenon that consists of various physiological parameters (Poerio et al.,2018). Neuroimaging research has revealed trait-level differences in resting-state brain activity between people who experience ASMR (Poerio et al.,2018). For the population that experiences ASMR, it has been shown that there is reduced and increased connectivity in a number of areas called Default Mode Network (DMN) (Poerio et al.,2018). Default Mode Network consists of angular gyri, posterior cingulate, medial temporal gyri, bilateral inferior/ parietal cortices and medial prefrontal cortices (Smith et al.,2017). This network around the brain is linked with internal mental activity and self- referential processing (Poerio et al.,2018).

For the population that experiences autonomous sensory meridian response, there is reduced resting-state functional connectivity between frontal, sensory and attentional regions of DMN, such as the sensory cortex and the thalamus (Poerio et al.,2018). With the atypical sensory input, atypical thalamic connectivity may lead to the tingling sensation during ASMR (Smith et al.,2017) Interestingly, some research shows that increased DMN activation around the regions related to observing highly moving and emotional artwork (Poerio et al.,2018). Additionally, DMN activities increased in the regions around the part of executive control and visual resting-state networks.

Even in FMRI, study results coincide with the above results. DMN of individuals with ASMR showed significantly less connectivity and increased connectivity around specific regions of the DMN (Smith et al., 2017).

Decreased connectivity among:

- Right superior and middle temporal gyri

- Precuneus

- Superior frontal gyrus

- Posterior cingulate

- Left superior temporal gyrus

- Medial frontal gyrus

- Medial dorsal thalamus

Increased connectivity among:

- Some regions of the cortex (anterior medial pre-frontal cortex)

- Between the left superior and middle frontal gyri

- Left middle temporal gyrus

- Right precuneus

- Frontal lobe

- Right middle occipital gyrus (Smith et al., 2017)

However, these results are preliminary. They require further research being statistically significant but not necessarily clinically (Smith et al.,2017).

ASMR & Sleep

In research conducted by Barratt and Davis in 2015, through Likert style questions, they concluded that 98% of the participants agree that ASMR helps with relaxation. Moreover, 82% of the participants agree that ASMR helps with sleeping. In addition, research showed that around 81% of the participants reported that the most common time for engagement with ASMR is before going to sleep at night. With these findings, it shows that people prefer to have ASMR before sleep, and it helps them to relax(Barratt & Davis, 2015).

Even though there is currently no research on the science behind how ASMR can induce sleep. However, there is research supporting that relaxing classical music can improve sleep quality. Research conducted by Johnson in 2003 showed that use of music can decrease time to sleep onset and the number of nighttime awakenings. It increased satisfaction with sleep. Considering the similarity between music and ASMR, ASMR might have the potential to induce sleep in people, but further research is required to make this conclusion (Johnson, 2003).

ASMR & Babies

Hushed whispers and repetitive toy sounds all a form of autonomous sensory meridian response, also called ASMR. Although ASMR was originally aimed at adults, it is also used by parents and caretakers to help babies and toddlers fall asleep (“What Is ASMR, and How Can It Benefit Your Kid's Mental Health?”, 2020). Although there is very little research published on babies and their experience with ASMR, some parents still opt to rely on it to help their baby remain calm.

As of June 2018, there are over 10 million ASMR videos available with many of them being kid friendly and featuring unicorns or slimy substances. This huge number of videos shows that more parents are utilizing them to comfort their babies (“ASMR and Kids: What is It, and What are the Pros and Cons? - Detroit and Ann Arbor Metro Parent”, 2020).

ASMR & Synesthesia

Synesthesia is a perceptual condition characterized by consistent sensory associations due to the atypical blending of the senses. Synesthetic individuals often experience unrelated secondary sensations to specific sensory stimuli; for instance, feeling a specific taste in the mouth when hearing a particular sound (Hubbard & Ramachandran, 2005).

Interestingly, 5.9% of people with ASMR also experience synesthesia, suggesting an overlap in their physiological mechanism (Barratt & Davis, 2015). The sensory associations are highly consistent and reliable over time for both synesthesia and ASMR. The same stimulus is able to automatically trigger the same corresponding atypical response, such as ASMR tingles along the back of the neck and upper spine (Fredborg et al., 2017).

However, there are differences that set the two sensory conditions apart. For synesthesia, secondary sensations in response to primary stimuli are automatic and uncontrollable. This contrasts with ASMR, where secondary sensations are autonomous and can be interrupted by voluntarily disengaging from the stimuli (Fredborg et al., 2017).

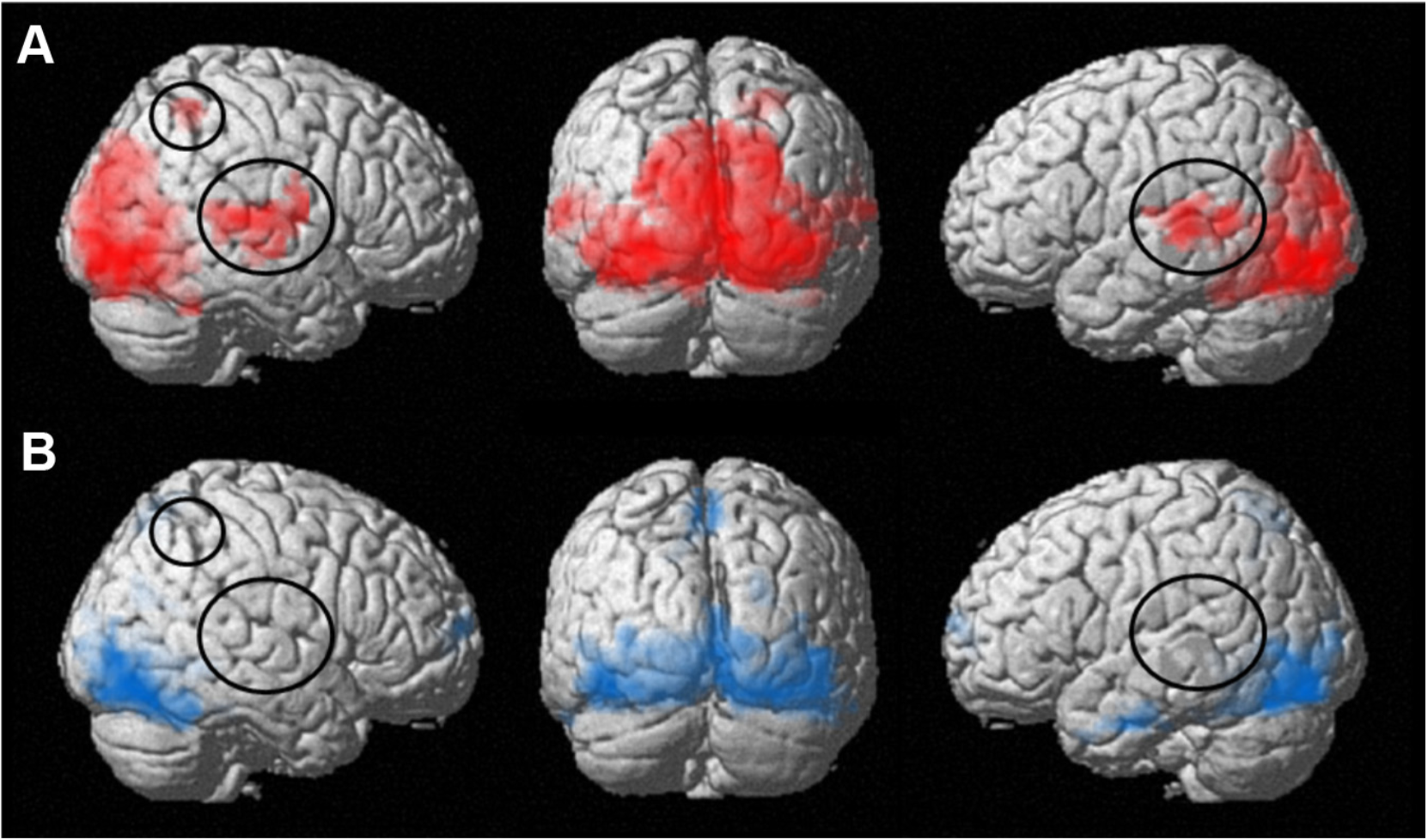

Both conditions are found to be associated with changes in neural impulses that functionally connect the different regions of the brain (Smith et al., 2017). Functional MRI scans taken at rest revealed a noticeable increase in functional connectivity between brain regions that together comprise the default mode network, one of the most prominent resting-state networks studied thus far (Smith et al., 2017).

Grapheme-color synesthesia, a common form of synesthesia, results from not only increased intra-network functional connectivity, but also stronger intrinsic inter-network connectivity within the brain. These signs of hyperconnectivity captured by functional MRI help to explain part of the physiological basis for the consistency and strength of synesthetic experiences (Dovern et al., 2012).

Figure 4: 3-D surface rendering of brain regions functionally connected with bilateral visual area V4 in grapheme-color synesthetes. Panels A and B represent synesthetes and control subjects respectively. The circled areas refer to brain regions functionally connected to V4 in synesthetes, but not in controls. Overall the functional connectivity of V4 with other brain regions, particularly those associated with visual color sensation, is more pronounced in synesthetes (Dovern et al., 2012).

Is ASMR Universal?

Although ASMR is known to help the mind relax, it does not work for every individual (What is ASMR?, n.d.).

For the individuals who do experience the benefits of ASMR, a tingling sensation is felt from the scalp and slowly makes its way through the body. This feeling of relaxation is associated with the release of a brain chemical known as “oxytocin”(Science Is Finding Out Why Some Love ASMR Videos and Others Hate Them, 2019).

Some people, however, may find ASMR annoying or not experience the benefits at all because their brains may fire differently from those who do report the effects of ASMR. Although this is not scientifically confirmed, it is believed that those who are not affected by ASMR have less activity in the areas of the brain associated with reward and emotional arousal (Science Is Finding Out Why Some Love ASMR Videos and Others Hate Them, 2019).

ASRM & Misophonia

In recent years, some researchers suggested that ASMR is related to misophonia, which is a disorder triggered by sound and causes anger and disgust. People with misophonia tend to be extremely sensitive to certain sounds. Studies had shown that many people suffer from misophonia also report experiencing ASMR. They have reported that people who experience misophonia 50% of them also experience ASMR. Interestingly, researchers found that people who experience ASMR also have elevated results on the Misophonia Symptom Scale (Fredborg, Clark, & Smith, 2018).

ASMR and misophonia represent the opposite ends of a spectrum of experience. For a particular sound, someone may feel highly relaxed while listening to it, ASMR response. Other individuals may find it a highly aversive, misophonia response (Fredborg, Clark, & Smith, 2018).

ASMR & Disorder

Rather than a cause of medical attention, ASMR actually offers therapeutic benefits for people who rely on the tingling sensations to seek short-term relief from depression, stress and chronic pain (Barratt & Davis, 2015).

ASMR is mostly subject to the conscious control of individuals, who can elect to disengage from the triggering stimulus to stop undesired ASMR tingles (Fredborg et al., 2017). In contrast to neural disorders that disrupt daily functioning, ASMR is often actively sought out by people to achieve mental relaxation. It might come as a surprise that as much as 82% of survey respondents use ASMR to sleep better, while 70% of them found ASMR useful for dealing with stress (Barratt & Davis, 2015).

People experiencing ASMR are more likely than controls to experience misophonia as an accompanying symptom, which is the heightened sensitivity and aversion to sounds that elicit intense feelings of anger, anxiety, and disgust (Scofield & Hostler, 2019). Despite not being officially recognized as a disorder, misophonia has been shown to interfere with daily functioning as it triggers unpredictable bouts of emotional outbursts (Webber et al., 2014). The tendency for ASMR individuals to also experience misophonia at times suggests that the two sensory conditions may be situated at opposite ends of the auditory sensitivity spectrum; while ASMR produces pleasurable sensations, misophonia does the exact opposite and can be mentally debilitating (Scofield & Hostler, 2019). Hence, precautions must be taken when seeking ASMR as a therapeutic intervention.

ASMR & Anxiety

A lot of people have started adapting to ASMR as a potential new digital therapy for mental health. Viewers use these videos to trigger ASMR which promotes relaxation and sleep. Some viewers believe AMR is an antidote to depression and anxiety. A wide population of people watch ASMR videos to combat stress and anxiety.

There are some primary studies looking at ASMR and it's overall effect on human mental well-being. One study looked at ASMR and how it impacts the mental state of humans (Barratt & Davis, 2015). Data obtained illustrated temporary improvements in symptoms of depression and chronic pain in those who engage in ASMR (Barratt & Davis, 2015). This study involved 475 participants. An online questionnaire was conducted to gather information on the prevalence of ASMR features and why individuals engage in ASMR(Barratt & Davis, 2015). Many participants reported that ASMR contributed to uplifting mood and pain relief (Barratt & Davis, 2015). ASMR is becoming more common and more used by people to help mental health.

Another article looked at changes in affect and the physiology of ASMR. There were 2 studies conducted: one large-scale online experiment and one laboratory study (Poerio, Blakey, Hostler & Veltri, 2018). Both these studies test the emotional and physiological correlates of ASMR response on the human body (Poerio, Blakey, Hostler & Veltri, 2018). Findings suggest that ASMR was associated with reduced heart rate and an increased skin conductance levels as well as ASMR is a reliable experience that may be beneficial to the mental and physical health (Poerio, Blakey, Hostler & Veltri, 2018).

Is ASMR Safe?

Although there are debates that question whether ASMR is actually effective, there are no dangers associated with it. In fact, ASMR is no different than listening to relaxing music or sounds such as rain or wind to help the mind with relaxation (Is ASMR Dangerous? Hearing Is Believing—Hooke Audio, 2018).

ASMR is perfectly safe and have been known to even help individuals with relieving symptoms associated with anxiety, depression or insomnia (If You Love ASMR Videos, It Could Give You A Mental Health Boost, 2018).

Conclusion

Autonomous sensory meridian response has recently become well-known. The science of ASMR is complex as it relates to physiological parameters. ASMR for babies is commonly used with over 10 million ASMR videos available online. Not everyone responds to ASMR, some people have reported a disgusting feeling in association with it. Sometimes ASMR can be mentally debilitating, which is why precautions must be taken when seeking ASMR as a therapeutic intervention. It is also used to help cope with anxiety and stress. Overall, ASMR is perfectly safe and can be potentially effective.

References

ASMR and Kids: What is It, and What are the Pros and Cons? - Detroit and Ann Arbor Metro Parent. (2020). Retrieved 21 March 2020, from https://www.metroparent.com/daily/health-fitness/mental-health-self-care/asmr-and-kids- what-is-it-and-what-are-the-pros-and-cons/

Barratt, E. L., & Davis, N. (2015). Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR): a flow-like mental state. Peerj, 3, e851. doi: 10.7717/peerj.851

Brain tingles: First study of its kind reveals physiological benefits of ASMR. (2018, June 21). Retrieved from https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/06/180621101334.htm

Carson, E., & Dziekan, M. (2019, May 9). Tingle all the way: ASMR videos chill you out one soap curl at a time. Retrieved March 18, 2020, from https://www.cnet.com/news/tingle-all-the-way-asmr-videos-chill-you-out-one-soap-curl-at-a-time/

Dovern, A., Fink, G. R., Fromme, A. C. B., Wohlschläger, A. M., Weiss, P. H., & Riedl, V. (2012). Intrinsic network connectivity reflects consistency of synesthetic experiences. Journal of Neuroscience, 32(22), 7614-7621.

Etchells, P. (2016, January 8). ASMR and 'head orgasms': what's the science behind it? | Pete Etchells. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/science/head-quarters/2016/jan/08/asmr-and-head-orgasms-whats-the-science-behind-it

Fredborg, B., Clark, J., & Smith, S. D. (2017). An examination of personality traits associated with autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR).

Fredborg, B. K., Clark, J. M., & Smith, S. D. (2018). Mindfulness and autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR). PeerJ, 6. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5414

Frontiers in psychology, 8, 247. Hubbard, E. M., & Ramachandran, V. S. (2005). Neurocognitive mechanisms of synesthesia. Neuron, 48(3), 509-520.

Is ASMR Dangerous? Hearing Is Believing—Hooke Audio. (2018). Retrieved March 19, 2020, from https://hookeaudio.com/blog/asmr/is-asmr-dangerous-hearing-is-believing/

If You Love ASMR Videos, It Could Give You A Mental Health Boost. (2018). Bustle. Retrieved March 19, 2020, from https://www.bustle.com/p/is-asmr-good-for-you-a-new-study-shows-it-could-have-mental-health-benefits-9689870

Johnson, J. E. (2003). The Use of Music to Promote Sleep in Older Women. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 20(1), 27–35. doi: 10.1207/s15327655jchn2001_03

Mooney, A., & Klein, J. (2016, September). ASMR Videos Are the Biggest YouTube Trend You've Never Heard Of. Retrieved March 18, 2020, from https://www.thinkwithgoogle.com/consumer-insights/asmr-videos-youtube-trend/

Poerio, G., Blakey, E., Hostler, T., & Veltri, T. (2018). More than a feeling: Autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) is characterized by reliable changes in affect and physiology. PLOS ONE, 13(6), e0196645. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196645

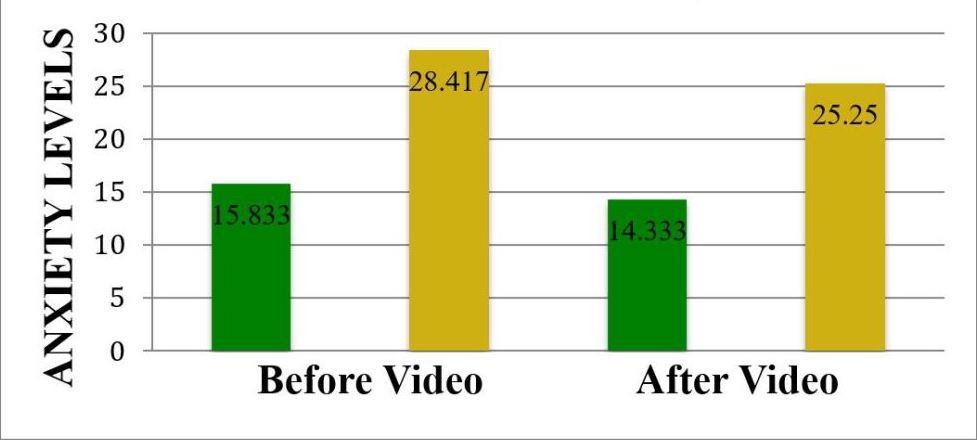

Richard, C. (2017, July 1). Undergraduate student shares results of research project about ASMR and anxiety. Retrieved March 18, 2020, from https://asmruniversity.com/2017/07/01/stacey-watkins-asmr-research-anxiety/

Science Is Finding Out Why Some Love ASMR Videos and Others Hate Them. (2019, February 12). HowStuffWorks. https://science.howstuffworks.com/life/inside-the-mind/human-brain/science-is-finding-out-why-some-love-asmr-videos-and-others-hate-them.htm

Smith, S. D., Katherine Fredborg, B., & Kornelsen, J. (2017, August). An examination of the default mode network in individuals with autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27196787

Scofield, E., Hostler, T. (2019). A Quantitative Study Investigating the Relationship between Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR), Misophonia and Mindfulness.

The Science Behind ASMR – The ASMR. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.theasmr.com/the-science-behind-asmr/

What Is ASMR, and How Can It Benefit Your Kid's Mental Health?. (2020). Retrieved 21 March 2020, from https://www.parent.com/what-is-asmr-and-how-can-it-benefit-your-kids-mental-health/

What is ASMR? (n.d.). Sleep.Org. Retrieved March 19, 2020, from https://www.sleep.org/articles/what-is-asmr/

Webber, T. A., Johnson, P. L., & Storch, E. A. (2014). Pediatric misophonia with comorbid obsessive–compulsive spectrum disorders. General hospital psychiatry, 36(2), 231-e1.