This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Anorexia

Overview

Introduction

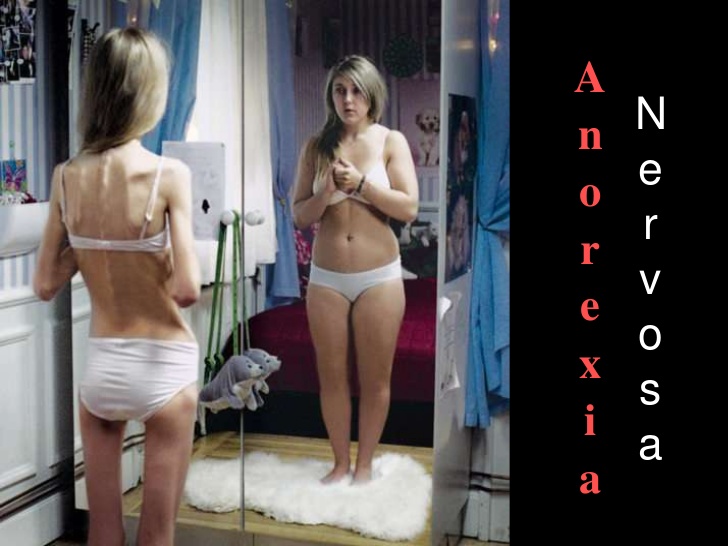

Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a life threatening mental illness that typically begins around puberty but can occur at any age. It is characterized by persistent behaviours that interfere with maintaining an adequate weight for health, a powerful fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, disturbance in how the person experiences their weight and shape and the individual not fully appreciating the seriousness of their condition. If these characteristics are seen over a period of a least three months an individual can be diagnosed with anorexia (Nedic, 2014).

Persistent behaviours that interfere with maintaining an adequate weight for health includes: restricting food, compensating for food intake through intense exercise, and/or purging through self-induced vomiting or misuse of medications like laxatives, diuretics, enemas, or insulin. In the past anorexia used to be specifically associated with weight loss, making it difficult to recognize in children and adolescents. Weight gain is needed in children and adolescents in order to support healthy growth and development. Therefore, failing to gain weight or grow is just as concerning as weight loss (Nedic, 2014).

The powerful fear of gaining weight or becoming fat is common in individuals with anorexia. Individuals may feel this fear ever if they are maintaining a weight that is too low for their health. Often this fear will result in individuals using a variety of techniques to evaluate their body size or weight - behaviour known as body checking. Frequent weighing, obsessive measuring of body parts and the persistent use of mirrors to check for “fat” are common techniques used to body check (Nedic, 2014).

There is a disturbance in how the person experiences their weight and shape meaning that the person overestimates their body size, they usually evaluate it negatively. Individuals feel that their weight and shape matter more than anything else about them (Nedic, 2014).

Typically, an individual with anorexia does not fully appreciate the seriousness of their condition as it has been linked to cardiac arrest, suicidality, and other causes of death. Anorexia was previously associated with the loss of menstrual periods which made it difficult or impossible to identify in males or in pre-pubescent children or teens, however this is no longer necessary for diagnosis (Nedic, 2014).

History

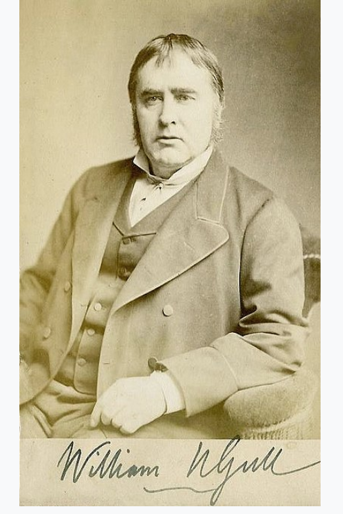

Though not termed as anorexia nervosa at the beginning, this condition has been seen since the Hellenistic era and has continued through the Middle Ages (Pini et al., 2016). During these times, it was focused on religious fasting, spiritual purity and self- sacrifice. The term, anorexia nervosa was first established by Sir William Gull in 1873; Sir William Gull made observations of this condition and presented it to the British Medical Association in Oxford, England (Pini et al., 2016). At the same time, French physician, Ernest- Charles Lasègue also published details of cases the same year that the term was created, his work concentrated more on the psychological symptoms and examined the role of parental and family interactions (Pini et al., 2016). Anorexia nervosa was the first eating disorder to be placed into the first DSM edition and it was not until 1980 that the body image disturbance criteria was a diagnostic criterion (Pini et al., 2016). In the DSM 5, it is now under the “other specified feeding or eating disorder” along with bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), rumination disorder and pica (Pini et al., 2016).

Etiology

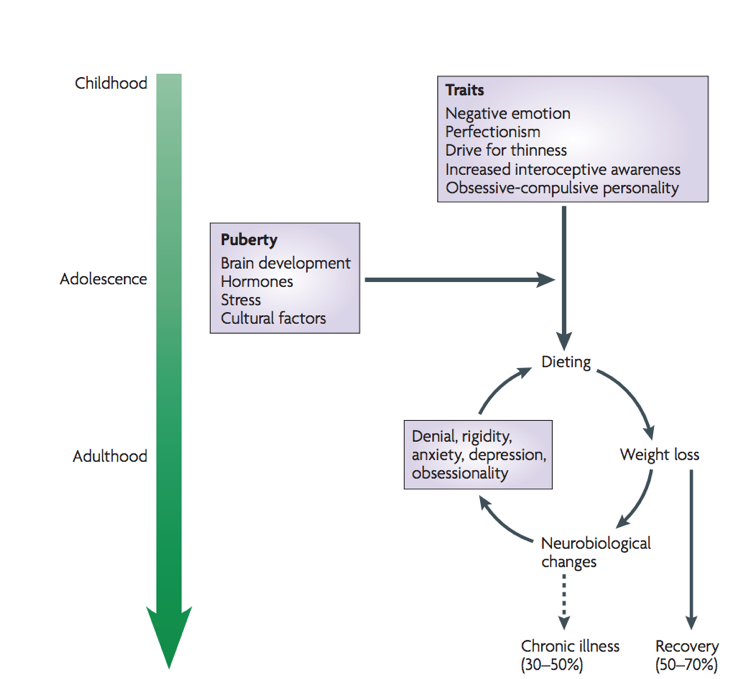

Anorexia nervosa has no specific origin as it is difficult to separate whether the starvation causes the cascade in the body or whether it is the anorexia condition itself. Three major aspects have been highlighted as areas of special interest including the biology, psychology and environmental factors.

Looking at the biology of the condition, it is seen that heritability can have a major influence in its development. The incidence rates of heritability can be influenced by from 50%-75% through various assessments (Bulik, 2010). It should also be noted that there is no direct link of a gene affecting however a cascade if genes have not been identified. The serotonin pathway as described in the pathophysiology has been highlighted as a key factor in the progression of anorexia nervosa (Kaye et al. 2009).

The psychology behind the condition indicated that those with a tendency of obsessive-compulsive personality traits are individuals with an increased probability of developing this. Anorexia nervosa alleviates the propagation of anxious behaviours in lieu of a continuous fear of food and gaining weight (Rothenburg, 1988).

Environmental factors, especially through the influence of western culture, drives the desire to be thin as it represents success and worth. The media often perpetuates a culture of continuous scrutiny over one’s body, idolizing the thin (Mayo Clinic, 2018).

Epidemiology

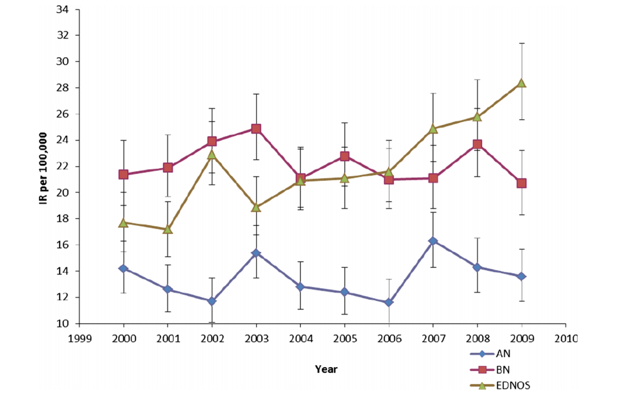

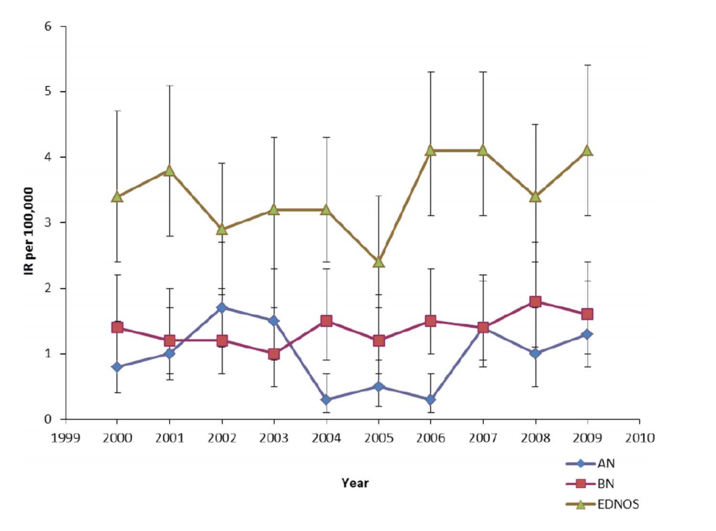

The lifetime prevalence, incidence rates and 5 year recovery rates were calculated from data from 2882 women from 1975-1979 birth cohorts of Finnish twins (Keski-Rahkonen et al., 2007). The incidence in women aged 15 to 19 years was 270 per 100,000 person- years (Keski-Rahkonen et al., 2007). The 5 year clinical recovery rate was 66.8% at which complete or nearly complete psychological recovery was seen (Keski-Rahkonen et al., 2007). Western countries have a higher prevalence than non- Western countries (Keski-Rahkonen et al., 2007).

The average prevalence in Western Europe and North America is 0.3% (National Eating Disorder Information Centre, 2018) . The lifetime prevalence in females is 0.9% and in males is 0.3%; note lifetime prevalence is defined as the proportion of individuals in a population that at some point in their life have experienced the disease (National Eating Disorder Information Centre, 2018). The prevalence of AN in Canada is 0.3% in adolescent and young women (National Eating Disorder Information Centre, 2018).

Risk Factors

It has been found that there are several risk factors for developing anorexia. These include: perfectionism, negative self-evaluation, obesity, family history of anorexia, affective disorder, substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive disorder and a stress/trigger. It was also found that a lot of these risk factors were correlated to being risk factors of other psychological conditions and that they could have been acquired genetically (Fairburn, Cooper, Doll & Welch, 1999). It should also be mentioned that all of the aforementioned risk factors are not known in detail - their significance is unknown at this point. Social determinants, culture and family also play a role, and vary significantly (“Anorexia Nervosa-What Increases Your Risk”, 2018).

Diagnosis / Symptoms

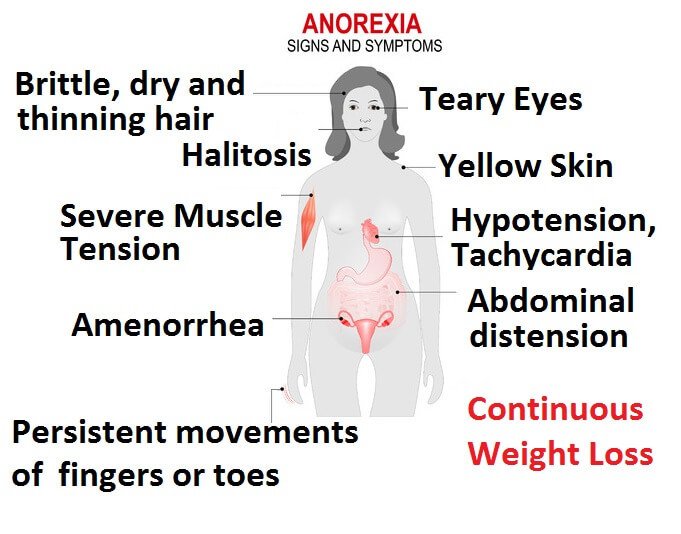

Anorexia is not a straightforward disease to diagnose. It can all be agreed however that a low body weight is the main component for diagnosis. Following such, an individual may also possess fear for gaining weight, as well as have an altered interpretation of healthy weight (Rothenberg, 1988). The first step for diagnosis by the physician is to confirm that the weight loss is not attributed by any other factor. He or she may run several tests to confirm this: a physical exam to determine if the patient’s BMI is under 17.5, and blood tests to measure electrolytes, protein, and thyroid, liver and kidney function. If the tests reveal no abnormalities and the physician believes it is mental, a referral to a mental health professional is commonly seen (“Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa”, 2018). The second step for diagnosis is conducted by a mental health professional, who utilizes the Diagnostic & Statistics of Mental Disorders Manual 5 (DSM-5) as an aid. The professional determines through questionnaires, and evaluations if the patient has fears of gaining weight or has restrictive eating patterns (“Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa”, 2018). Some common symptoms for patients with anorexia are: extreme weight loss, fatigue, insomnia, dizziness or insomnia, constipation and abdominal pain, low blood pressure, and dehydration. Lastly, some patients present with bulimic symptoms - binging and purging (“Anorexia nervosa - Symptoms and causes”, 2018).

Several complications can arise from AN including gastrointestinal, cardiovascular, pulmonary and skeletal system complications (Mitchell & Crow, 2006). Gastric dilation, mucosal necrosis, delayed gastric emptying, gastric motor dysfunction, constipation, pancreatitis, and perforated ulcers (Mitchell & Crow, 2006). Cardiovascular complications include arrhythmias, acrocyanosis, tachycardia, bradycardia, and hypotension (Mitchell & Crow, 2006). Lastly, skeletal complications include decreased bone mineral density, which leads to osteopenia and other bone- related complications (Mitchell & Crow, 2006).

Pathophysiology

Biological Effects

Research demonstrates that women with AN will usually overestimate their own body dimensions whereas healthy women will usually tend to underestimate them. The cognitive-affective component of a disturbed body image comprises of negative-body related attitudes and emotions (Vocks et a, 2010). Although it seems that in Western cultures discontent with one’s shape and weight is common those that have eating disorders seem to exceed those of healthy women in terms of body dissatisfaction.

Although AN is characterized as an eating disorder, it remains unknown whether there is a primary disturbance of appetitive pathways, or whether there could be other causes such as anxiety or obsessive preoccupation with weight gain.

Serotonin Function

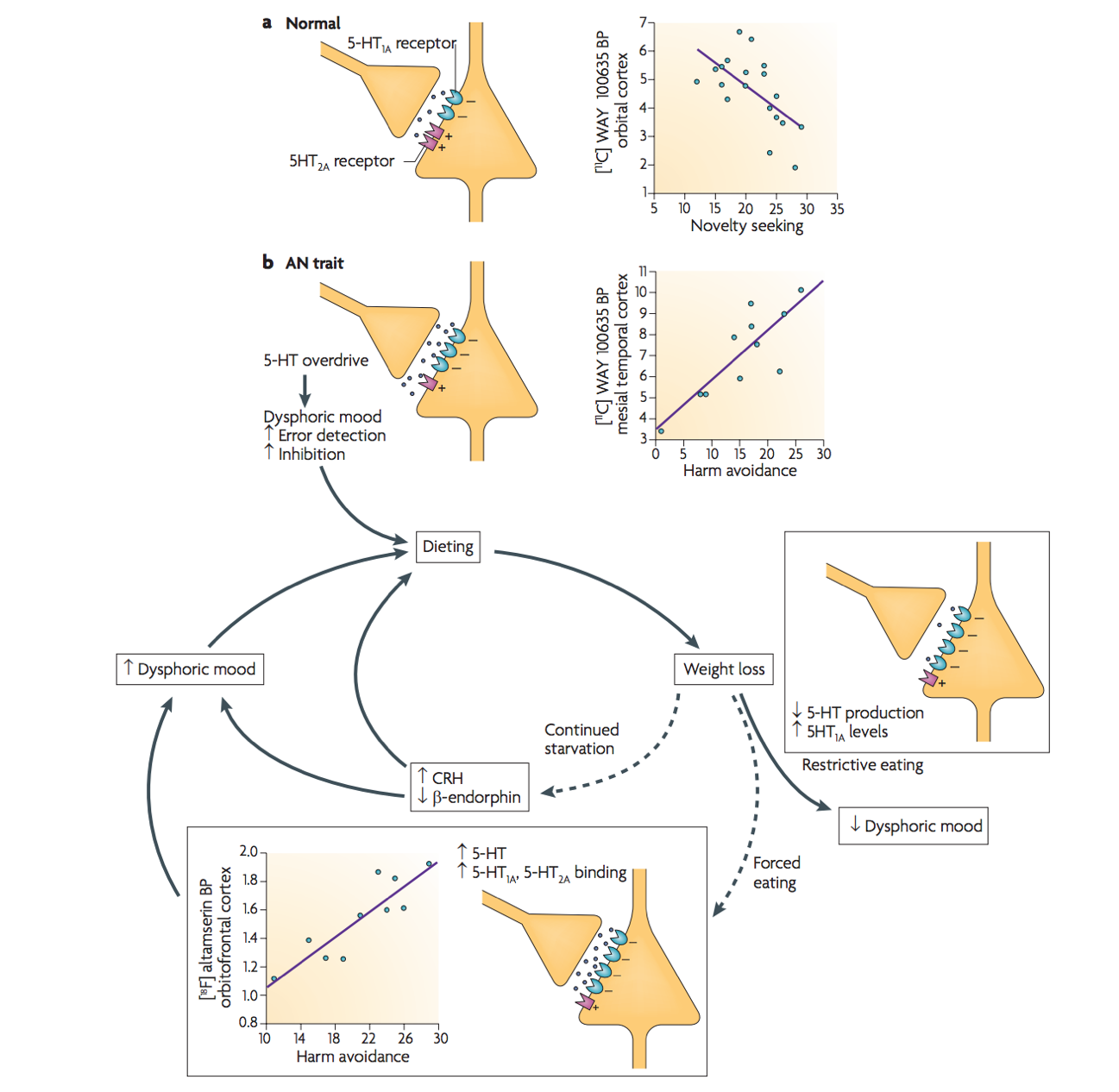

The 5-HT serotonin system has been studied in individuals that have AN, to suggest that it is possible that this neurotransmitter system plays a role in many symptoms of anorexia such as enhanced satiety, impulse control and mood.

It has been said that these might contribute to an increase in satiety and a more anxious harm-avoidant temperament. Individuals with Anorexia are said to have a reduction in dysphoric mood. Starvation is associated with an increase in postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptor binding potential. Additionally the binding of the 5-HT-2A receptor is positively correlated with harm avoidance in individuals that suffer from AN (Kaye et al, 2009). Individuals with AN will usually pursue starvation ass an attempt to avoid the dysphoric mood that comes as a consequence due to this increased stimulation of postsynaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors and therefore makes eating and weight gain aversive (Kaye et al , 2009).

Anterior Insula

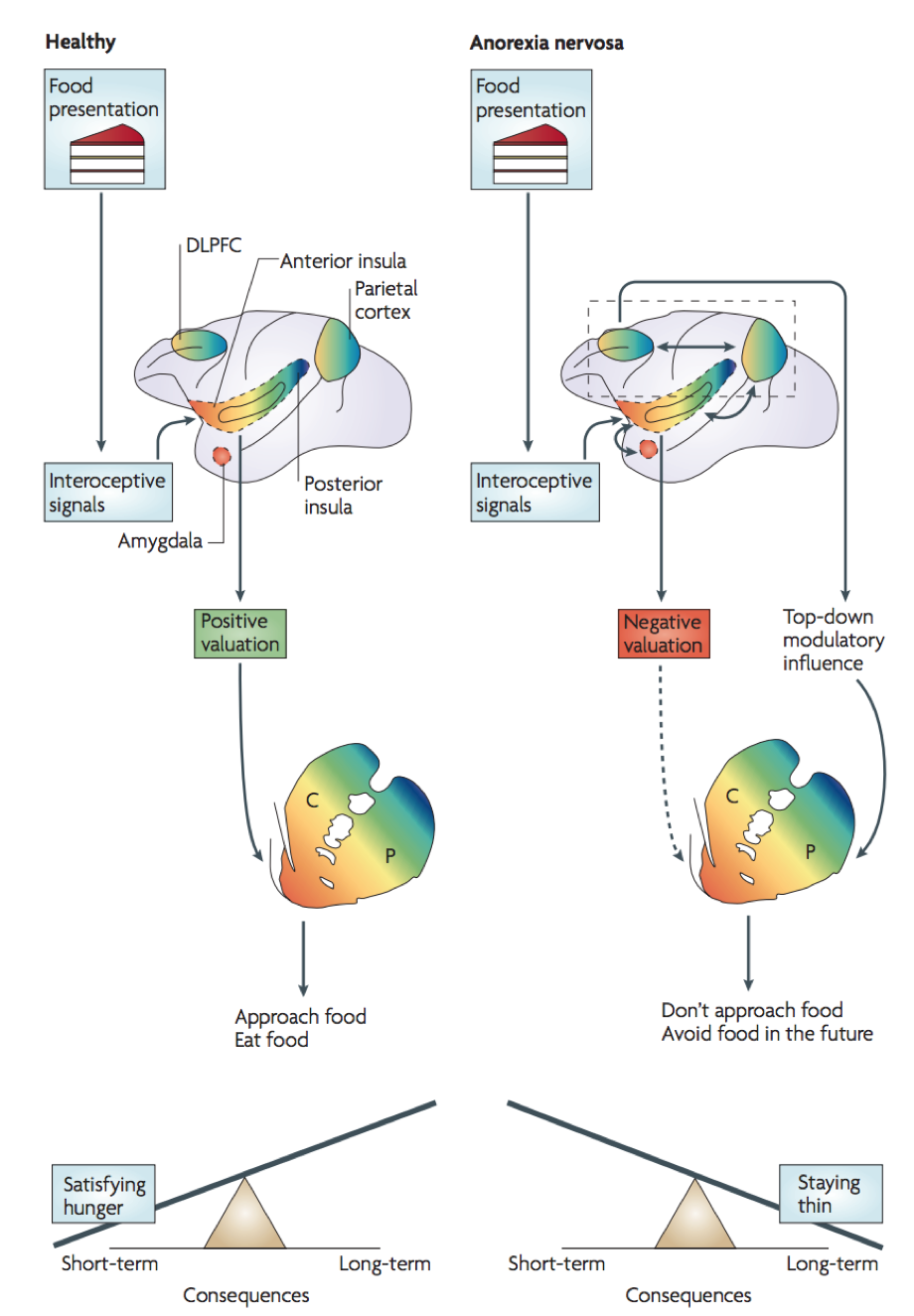

The anterior insula is involved in the idea of interoceptive processing which explores the feelings of pain, temperature itch etc. The integration of these internal feelings allows to gain a sense of the physiological condition of the entire body. Altered insula activity supports the idea that individuals with AN have an altered sense of self. As mentioned those that have anorexia experience a strong conflict between the biological need for food and an acquired aversive association with the food. Individuals do not recognize the symptoms of malnutrition, so they do not respond to hunger and they do not have the motivation to change. This is all due the idea of disturbed interoceptive awareness (Kaye et al, 2009).

Individuals who have AN will usually experience an aversive visceral sensation when they are exposed to food or a form of food-related stimuli. This creates a bias towards the reward-related properties of food and creates a more negative emotion. This minimizes the exposure to food stimuli (Kaye et a, 2009).

Current Treatments

Through research, it is clearly exemplified that anorexia nervosa is merely not an eating disorder but dives into deep-seeded issues an individual may have. The first step includes the acceptance of their disorder and familial assistance prepares individuals for the upcoming services. A psychiatrist is beneficial for the prescription of medications including antidepressants as several individuals experience anxiety in accordance with the eating disorder (Kaye et. al 1999). Enlisting the services of a nutritionist will be of benefit as managing the fear of food will be adequately guided by a professional ensuring the appropriate quality and quantities of food are provided.

The implementation of cognitive behavioural therapy will use psychotherapy as a means to address the underlying thoughts behind the condition. This will recognize those symptoms and assist in a healthy method of alleviating those notions (Kaye et al. 1999). Managing a long term eating disorder will be a difficult challenge however with the enlistment of these services, recovery will be possible.

Conclusion

The causes of anorexia nervosa are not completely understood by medical and psychological professionals, it is acknowledged that an array of biological, social, genetic, and psychological factors play a role in increasing the risk of its onset. The societies we live in have strong beliefs and attitudes toward just about everything. Different groups within a given society adapt these beliefs, attitudes and behaviours altering our beliefs and attitudes toward ourselves and our bodies. Our feelings and behaviour also affect our physical make-up and health. The first step in the recovery process is realizing that our food- and weight-related behaviours are hurting us, rather than helping us. Once an individual is able to realize this, help can be found or offered in a variety of days. Family members and friends may also benefit from information and help. It is possible to prevent the development of food and weight fixation and eating disorders. It is also possible to prevent existing eating disorders from getting worse. It begins with learning and improving our own self-esteem and body image, to working with others and making positive societal changes.

References

Anorexia nervosa - Symptoms and causes. (2018). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 26 March 2018, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anorexia/symptoms-causes/syc-20353591

Anorexia Nervosa-What Increases Your Risk. (2018). WebMD. Retrieved 26 March 2018, from https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/anorexia-nervosa/anorexia-nervosa-what-increases-your-risk

Bulik CM, Thornton LM, Root TL, et al. Understanding the relation between anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa in a Swedish national twin sample. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:71-77.

Dell’Osso, L., Abelli, M., Carpita, B., Pini, S., Castellini, G., Carmassi, C., & Ricca, V. (2016). Historical evolution of the concept of anorexia nervosa and relationships with orthorexia nervosa, autism, and obsessive–compulsive spectrum. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment,12, 1651.

Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. (2018). Healthdirect.gov.au. Retrieved 26 March 2018, from https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/diagnosis-of-anorexia-nervosa

Fairburn, C., Cooper, Z., Doll, H., & Welch, S. (1999). Risk Factors for Anorexia Nervosa. Archives Of General Psychiatry, 56(5), 468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.468

Kaye, W., Strober, M., Stein, D., & Gendall, K. (1999). New directions in treatment research of anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Biological Psychiatry, 45(10), 1285-1292.

Keski-Rahkonen, A., Hoek, H. W., Susser, E. S., Linna, M. S., Sihvola, E., Raevuori, A., … & Rissanen, A. (2007). Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(8), 1259-1265.

Micali, N., Hagberg, K. W., Petersen, I., & Treasure, J. L. (2013). The incidence of eating disorders in the UK in 2000–2009: findings from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ Open, 3(5).

Mitchell, J. E., & Crow, S. (2006). Medical complications of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 19(4), 438-443.

Nedic. (2018). National Eating Disorder Information Center. Nedic.ca. Retrieved 24 March 2018, from http://nedic.ca/know-facts/overview

Rothenberg, A. (1988). Differential diagnosis of anorexia nervosa and depressive illness: A review of 11 studies. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 29(4), 427-432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0010-440x(88)90024-7

Statistics | National Eating Disorder Information Centre (NEDIC). (2018). Nedic.ca. Retrieved 24 March 2018, from http://nedic.ca/node/24