Table of Contents

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Origin & Background

The concept of post-traumatic stress is not a new one. War veterans returning from battle have been reporting symptoms of flashbacks, hyper-arousal, anxiety and depression, for hundreds of years (Malia, 2014). When Civil war veterans were first diagnosed, physicians referred to their symptoms as “Soldier’s Heart”, “Shell Shock” or “Combat Fatigue”. It wasn’t until 1980, that the American Psychiatric Association (APA) added Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III).

PTSD is broadly characterized by an extreme reaction to trauma that changes how a person thinks, feels and behaves (Malia, 2014). This can present in a variety of different ways, of varying severity, and causes considerable distress to the individual, usually affecting their ability to function normally. An individual who develops PTSD hasn't necessarily gone through a traumatic event, but may experience symptoms of traumatic stress indirectly from a trauma affecting close friends or family (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, 2016). The proximity, duration and severity of trauma exposure can affect whether or not you develop symptoms. For example, you are more likely to develop symptoms if you personally experience chronic, severe trauma such as childhood abuse, rather than an individual who witnesses one-time experience, such as a robbery (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

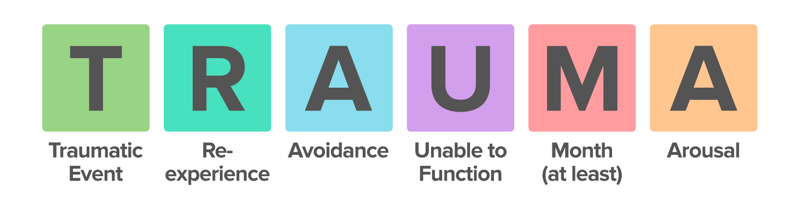

Figure 1: This image depicts the six main components of post-traumatic stress disorder (Sadock & Ruiz, 2015).

Normal Stress Reaction

Normally, when an individual is exposed to a threat, their sympathetic nervous system (fight or flight response) will be activated (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The sympathetic nervous system will release epinephrine & norepinephrine; pupils dilate, mouth dries, adrenal glands release norepinephrine, liver releases glucose, bladder inhibits urination and skin increases sweat production. The brain will release ACTH, cortisol and adrenaline, and heart rate will increase (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). When you are no longer exposed to the threat, the parasympathetic nervous system will kick in and all of these processes will reverse.

Post-Traumatic Stress Reaction

In a chronic stress situation, the brain has a tendency to over-estimate how much danger you are in. In this case, your stress system malfunctions and your body remain on high alert with your sympathetic nervous system activated. With constant activation, your brain will continue to release stress hormones such as ACTH, cortisol, and adrenaline (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

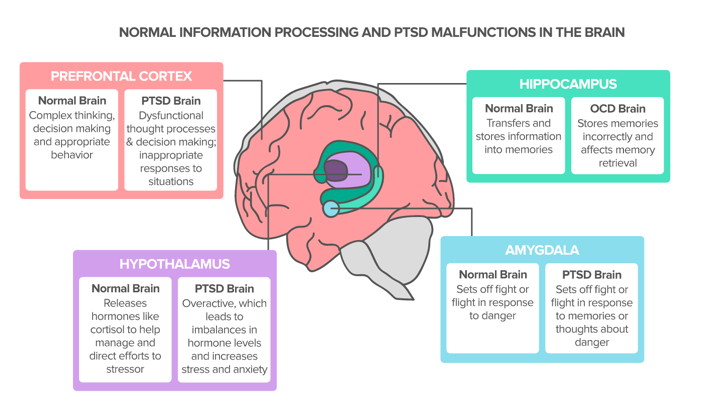

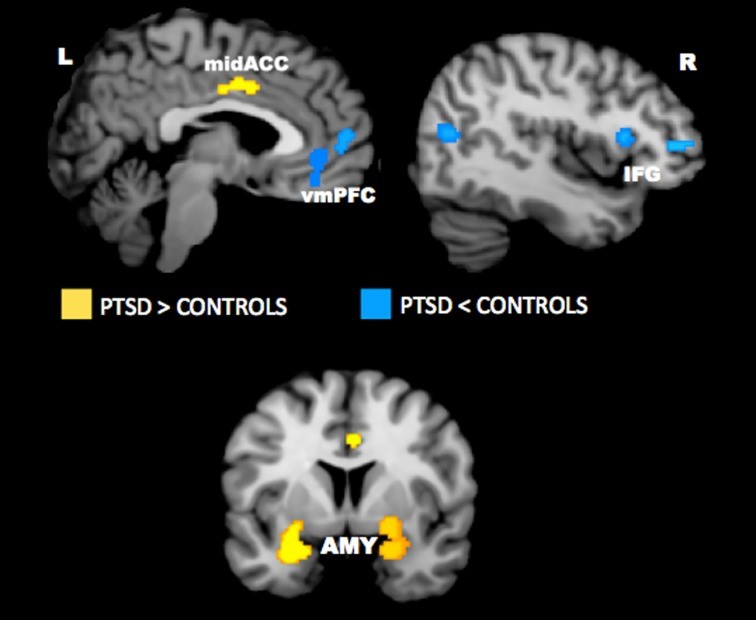

With continual hormone release, your brain will make mistakes interpreting the environment around you, and different structures will begin to respond differently (See Figure 2).

The symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder are often debilitating and interfere with an individual’s ability to work, go to school, and have meaningful relationships. If left untreated, they can become so severe that an individual may attempt suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Figure 2: This image shows how brain structures respond differently in an individual experience post-traumatic stress disorder (Sadock & Ruiz, 2015).

Symptoms

Post-traumatic stress disorder is characterized by four main types of symptoms: reliving the trauma through intrusive memories, experiencing emotional numbness and avoidance behaviour, portraying negative changes in thinking and mood as well as changes in physical and emotional reactions (PTSD Mayo Clinic, 2017).

The first set of symptoms are displayed as recurrent, unpleasant and distressing memories of the traumatic event. These could occur through reliving the traumatic event as if it were happening again. Intrusive memories could take a form of distressing dreams or nightmares about the traumatic event. The individual could also experience severe emotional distress or physical reactions to something that recalls the traumatic event. Individuals suffering with PTSD could also display avoidance behaviour. This behaviour is displayed through avoidance of talking about the traumatic event as well as avoidance of activities or people that recall the traumatic event. The third set of symptoms are characterized by negative changes in thinking and mood. These symptoms might include having negative thoughts about oneself, other people or the world as well as being hopeless about the future. Individuals could also experience memory problems, including not remembering important aspects of the traumatic event. It might also be difficult to maintain close relationships and feeling detached from family and friends. PTSD patients may also lack interest in activities once enjoyed and have difficulty experiencing positive emotions. This is often described as being emotionally numb. The last set of symptoms often displayed are changes in physical and emotional reactions. Changes in physical reactions might include being easily startled or frightened, being on guard or feeling in danger most of the time as well as displaying self-destructive behaviour (e.g., excess drinking, driving too fast). Changes in emotional reactions could display as being unable to concentrate or focus, being easily irritable, displaying angry outburst or aggressive behaviour as well as displaying overwhelming guilt or shame. Children of six years of age and older could display PTSD by re-enacting the traumatic event or aspects of the traumatic event through play. They could also experience frightening dreams that may or may not include aspects of the traumatic event (PTSD Mayo Clinic, 2017).

Diagnosis

DSM5 is the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). It is used by clinicians and researchers to diagnose and classify mental disorders. The aim of this diagnostic tool is to provide concise and explicit criteria to facilitate objective assessments of symptom presentations in a variety of clinical settings. The settings may include inpatient, outpatient, consultation, clinical, private practice and primary care (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The diagnostic criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, as listed in the DSM-5, is provided below:

DSM5 is the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). It is used by clinicians and researchers to diagnose and classify mental disorders. The aim of this diagnostic tool is to provide concise and explicit criteria to facilitate objective assessments of symptom presentations in a variety of clinical settings. The settings may include inpatient, outpatient, consultation, clinical, private practice and primary care (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The diagnostic criteria for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, as listed in the DSM-5, is provided below:

Figure 2: An image of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Criterion A (one required): The person was exposed to: death, threatened death, actual or threatened serious injury, or actual or threatened sexual violence, in the following way(s):

- Direct exposure

- Witnessing the trauma

- Learning that a relative or close friend was exposed to a trauma

- Indirect exposure to aversive details of the trauma, usually in professional duties (e.g., first responders, medics)

Criterion B (one required): The traumatic event is persistently re-experienced, in the following way(s):

- Intrusive thoughts

- Nightmares

- Flashbacks

- Emotional distress after exposure to traumatic reminders

- Physical reactivity after exposure to traumatic reminders

Criterion C (one required): Avoidance of trauma-related stimuli after the trauma, in the following way(s):

- Trauma-related thoughts or feelings

- Trauma-related reminders

Criterion D (two required): Negative thoughts or feelings that began or worsened after the trauma, in the following way(s):

- Inability to recall key features of the trauma

- Overly negative thoughts and assumptions about oneself or the world

- Exaggerated blame of self or others for causing the trauma

- Negative affect

- Decreased interest in activities

- Feeling isolated

- Difficulty experiencing positive affect

Criterion E (two required): Trauma-related arousal and reactivity that began or worsened after the trauma, in the following way(s):

- Irritability or aggression

- Risky or destructive behavior

- Hypervigilance

- Heightened startle reaction

- Difficulty concentrating

- Difficulty sleeping

Criterion F (required): Symptoms last for more than 1 month.

Criterion G (required): Symptoms create distress or functional impairment (e.g., social, occupational).

Criterion H (required): Symptoms are not due to medication, substance use, or other illness.

Specializations of PTSD:

- Dissociative Specification: in addition to meeting criteria for diagnosis, an individual experiences high levels of either of the following in reaction to trauma-related stimuli:

- Depersonalization: experience of being an outside observer of or detached from oneself (e.g., feeling as if “this is not happening to me” or one were in a dream).

- Derealization: experience of unreality, distance, or distortion (e.g., “things are not real”).

- Delayed Specification: full diagnostic criteria are not met until at least six months after the trauma(s), although onset of symptoms may occur immediately.

Etiology

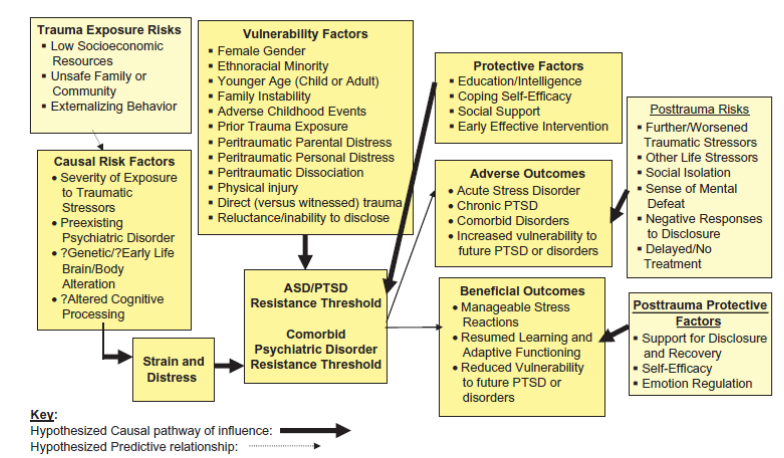

PTSD can develop in war veterans, children, and victims of natural disasters, sexual or physical abuse, family violence, and torture (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016). If a person directly experiences the traumatic event and there is bodily harm involved, the risk of PTSD is significantly higher (Ford et al., 2015). If a person witnesses the traumatic event taking place, and the event is on a large scale like instances of war and genocide, this can lead to a greater likelihood of developing PTSD. Repeated exposure to traumatic stressors, known as “retraumatization”, has proven to increase PTSD risk in individuals. This is still being debated as the criteria for what should be considered retraumatization has not been defined. PTSD is not triggered exclusively by traumatic experiences. Approximately 80-90% of people exposed to traumatic events do not develop PTSD. If the traumatic event occurs during one’s developmental years, the risk of developing PTSD is greater by 75% or more (Ford et al., 2015).

PTSD can develop at any age however, adolescents and young to midlife adults have a greater risk compared to children and elderly populations(Ford et al., 2015). Females and ethnic-racial minorities are also more susceptible to developing PTSD, the latter being a result of social and economic factors like racial stigma, discrimination, and poverty (Ford et al., 2015). Additional determinants that increase one’s likelihood of developing PTSD are childhood trauma, poverty, living through dangerous events, dealing with physical injuries and having a history of mental illness or substance abuse (National Institute of Mental Health, 2016). The type of response that follow these traumatic events are also risk factors, known as “peritraumatic” risk factors (Ford et al., 2015). Some of the main peritraumatic risk factors include high levels of initial distress characterized by increases in blood pressure, as well as dissociation and disorientation (Ford et al., 2015).

Figure 3. Risk Factors contributing to PTSD following traumatic events (Ford et al., 2015).

Genetics

Few research studies have been conducted on the genetics of PTSD and findings have generally produced inconclusive results (Sareen, 2017). A study analyzing the stress-related gene FKBP5 found that the presence of one of four polymorphisms on the gene was linked to an increased risk of PTSD in patients who had suffered child abuse. Patients without a history of child abuse did not show an increased risk (Sareen, 2017). Additionally, the FKBP5 genotype was found to be linked with peritraumatic dissociation a strong determinant for PTSD development (Wilker et al., 2014).

Pathophysiology

Neuroanatomy

The amygdala is responsible for stimulating the hippocampus to allow the brain to learn and create memories pertaining to specific threats (Vieweg, 2006). The initial reaction to a traumatic stressor is triggered by the amygdala. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for maintaining a cognitive understanding of the stimulus, including the event itself and the biopsychosocial responses of the traumatic event in the short and long-term (Vieweg, 2006). A study comparing a PTSD population and a control population found that individuals with PTSD showed reduced volume of the hippocampus, left amygdala, and anterior cingulate cortex compared to matched controls (Sareen, 2017). Other research has shown decreased functioning of the left hemisphere, which may explain the confusion experience in PTSD individuals when recalling the timeline of traumatic events. Some findings have shown increased central norepinephrine levels with down-regulation of central adrenergic receptors. Reduced glucocorticoid levels and up-regulation of receptors have also been observed in PTSD groups (Sareen, 2017).

Provocation studies

Provocation studies have shown anterior limbic-related areas involved with PTSD (Taber and Hurley, 2009). These include regions in the medial prefrontal, anterior cingulate, orbitofrontal, insular, and medial temporal cortices along with the amygdala (Taber and Hurley, 2009).

Cognitive activation studies

Cognitive activation studies have shown increased amygdalar activity and decreased medial prefrontal cortical responses to threat in PTSD groups (Taber and Hurley, 2009). Reduced responses in the rostral anterior cingulate cortex to emotional stimuli have also been observed (Taber and Hurley, 2009).

Morphometric studies

Morphometric studies have demonstrated reduced volume in several limbic areas,including the hippocampus, rostral anterior cingulate, dorsal anterior cingulate, and subcallosal cortices linked to PTSD (Taber and Hurley, 2009).

Research

A meta-analysis of imaging studies in PTSD was conducted. The observations found that the amygdala and mid-anterior cingulate cortex(ACC) was hyperactive, and the lateral and medial prefrontal cortex was hypoactive in PTSD for negative stimuli as opposed to neutral and positive stimuli (Hayes et al., 2012). A neurocircuitry model of PTSD suggests that abnormality in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) causes overactivation of the amygdala. This progresses to an inflated fear response and weakened fear extinction learning. The dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC), anterior insula, and amygdala contain a salience network that manages information of personal significance and is hyperresponsive in persons with anxiety (Hayes et al., 2012).

Figure 4. Analysis of functional neuroimaging studies where regions of hyperactivation in PTSD are indicated in yellow and regions of hypoactivation in PTSD are indicated in blue (Hayes et al., 2012).

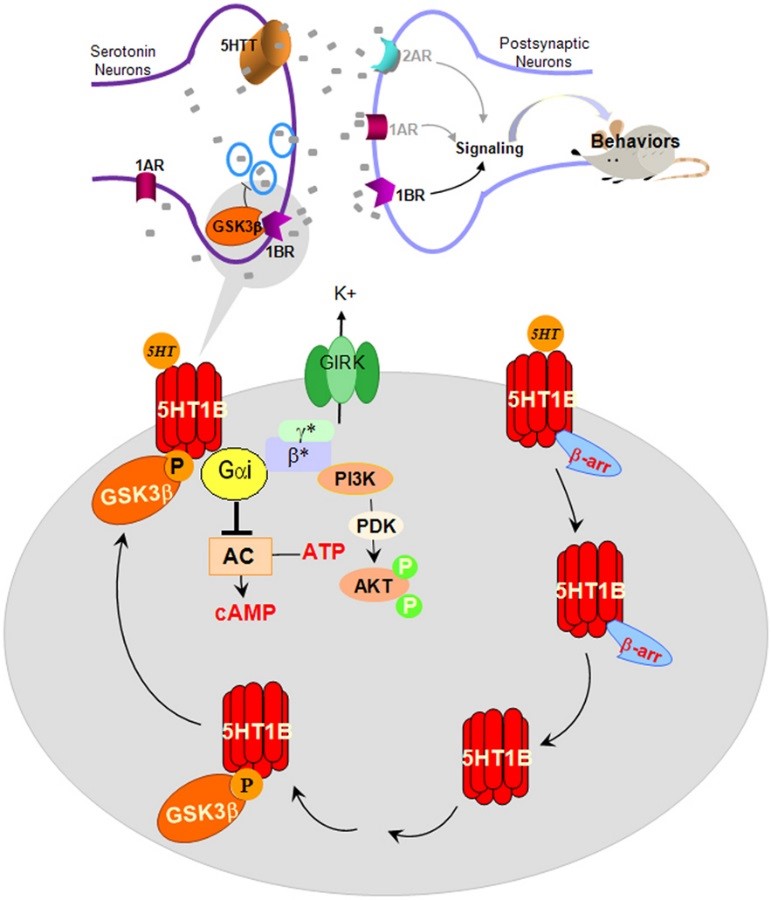

Neurobiology of Serotonin

In the brain, specifically in the brainstem medical and dorsal raphe nuclei, serotonin cell bodies (5-HT) regulate important functions (Kelmendi et al., 2016). Some vital roles that the 5-HT regulates include sleep, motor function, cognition and aggression (Sherin & Nemeroff, 2011). Previous research indicated that 5-HT is involved in stress response in patients with PTSD since the 5-HT neurons mediate anxiety producing effects on individuals through the 5-HT2 receptors (Sherin & Nemeroff, 2011). On the other hand, the 5-HT1A receptors regulate anti-anxiety producing effects from the median raphe. The 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors have been associated with disorders including PTSD (Bailey et al., 2013). Any changes in the functional 5-HT pathway may contribute to intrusive memories and impulsivity that is associated with PTSD symptoms(Bailey et al., 2013). Furthermore, Sari identified that the 5-HT1B receptor to be associated with PTSD, when there was a reduced amount of 5-HT1B receptor, the animals showed anxiety like behaviour (Sari, 2004).

Figure 5: The image represents the pathway of 5-HT1B receptors on Serotonin neurons and how it can affect behaviour in animals (Melatonin, 2017).

Treatments

Psychological Therapy

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

The goal is to teach patients with PTSD how to reduce their PTSD symptoms through managing their problems through how the patient thinks and act (“Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Treatment of PTSD”, 2017). Steps in the cognitive behaviour therapy include a therapist how goes through an interview to better understand the problem that the patients is facing (flashbacks, memories etc. (Shubina, 2015). Often, the patient is asked about their symptoms and asked to re-call their traumatic experience. Afterwards, the therapist will ask the patients to go through a series of sessions where their traumatic event is described and imagine again. The patient will focus on the negative effect which will increase their arousal. The patient is aided with relaxation exercise and reassurance that they can move past the experience. At the end of the session, the patient is asked to try to use the techniques outside of the session and confront triggers that produces anxiety (Shubina, 2015).

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing

In Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR), the goal of the treatment is to help reduce the symptoms of PTSD. The new treatment for PTSD involves hand motion by the therapist, similar to a pendulum swing that guides the patients’ eyes to move side to side (“Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) ”, 2015). There are eight phases in EMDR therapy. In the first step, the therapist will review the patients’ history and create a treatment plan (“Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy”, 2017). Then the therapist and patients will establish a relationship built on trust which includes the therapist fully disclosing the treatment in full detail. The patient goes through the assessment phase where the negative memories and feelings are brought to surface (“Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy”, 2017). The desensitization step involved the eye movement techniques where the patient is asked to focus on the therapists’ movement (“Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy”, 2017). The installation phase involves strength the positive reinforcement. The therapist will examine how the patients deals with the memories of trauma. The process may be repeated until the patients no longer experience negative feelings when traumatic memories re-surfaces. Then the closure phase, where the therapist debriefs the patients with support and ends the session. The re-evaluation phase occurs at the beginning of the next session and is when the therapist reviews the previous session (“Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy”, 2017).

Equine Therapy

Another type of therapy that some patients with PTSD often find helpful is alternative therapies including, Equine therapy. Equine therapy uses a horse to help patients with PTSD learn how to interact with others and learn more about themselves. There are three key components that must be in each session to be an Equine Therapy (“Equine Therapy for (PTSD) Post Traumatic Stress Disorder”, 2017)

- Conducted by a licensed medical professional

- Equine personal has at least 8, 000 hours of hands on experience with horses

- Usually, have two professional presents for the session (dual role or two people there)

The medical professional ensures that the patients received proper medical treatment and the Equine personal ensure for safely of the horse and patient. Some reasons why horses are used in equine therapy is because horses are patient, very cooperative and sociable towards human (Wilson, 2012; Masters, 2010). When patients interact with horses they often will feel encouraged because the size of the horses allow them to feel that they have physically overcome an obstacle. Also, even though horses are big, they are naturally vulnerable creatures which allows for the patient to connect with the animal on an emotional level. Horses are herd animals and depend on communication and relationship for survival (Wilson, 2012; Masters, 2010).

Pharmacotherapy

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRIs) are a common medication prescribed to patients with PTSD. SSRIs function to help ease symptoms such as depression and anxiety by increasing the level of serotonin uptake in the brain (Sangkuhl, Klein & Altman, 2009). Serotonin is a neurotransmitter involved in activities such as motor activity and hormone regulation (Sangkuhl, Klein & Altman, 2009). Previous research suggested that there is a deficiency in serotonin transport in the amygdala in patients with PTSD (Asnis, Kohn, Henderson & Brown, 2004). SSRIS function by blocking the pre-synaptic receptors that uptake serotonin into the neurons. SSRIS will block the uptake into neurons thus allowing an increase in serotonin into the synaptic cleft. The are only two types of SSRI medication approved by FDA for PTSD is Sertraline and Paroxetine (Asnis, Kohn, Henderson & Brown, 2004). Previous clinical studies on SSRI have mixed conclusions on the effectiveness of the drugs on patient with PTSD. However, a study conducted by Brady et al., conducted that patients who were treated with Sertaline had a decreased in PTSD symptoms by 43% compared to participants who received a placebo at 31% (Brady et al., 2000). In a more recent study by, Davidson et al., 2003, the researcher revealed a similar trend that Sertaline helped improved PTSD symptoms and decrease relapse in patients (Davidson et al., 2003).

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) function to suppress monoamine neurotransmitters including epinephrine and serotonin (“Three Types of Medications Used to Treat PTSD”, 2011) Therefore, there should be a higher level of monoanime neurotransmitters in the brain. MAOIs help PTSD patients in reducing the flashbacks, startled reaction and night terrors (“PTSD Medications - Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)”, 2015). In a study by Southwick et al., conducted a literature review on MAOIs treatment for PTSD. Researchers found that MAOIs helped patients by decrease the nightmares, PTSD flashbacks and re-experience their traumatic (Southwick et al., 1994).

Resources (Within Canada)

There are a lot of mental health resources that are related to people struggling with PTSD. Although some of these organizations don’t specialize specifically in PTSD, there are treatments or programs that they may provide. A lot of these organizations work together as opposed to separate and different organizations may handle different illnesses depending on the community that they are located in. If some can’t find what they are looking for at one of these organizations they will have connections to others that do. These five organizations are not the only five that deal with PTSD. There are a variety of them out there, the common ones were selected that were located in Canada.

Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Association of Canada (PTSDAC)

This is a not for profit organization that provides general information to aid individuals with PTSD, that may be susceptible to PTSD, caretakers, families, friends and co-workers. They provide you with a self-assessment tool that may help you understand the level of PTSD the individual has and if they should seek professional advice. Many of the symptoms of PTSD overlap with other illnesses and this checklist can help doctors create a more accurate diagnosis (PTSDAC, 2016).

Veterans Transition Network (VTN)

Veterans Transition Network looks to help people in the military with PTSD when they come back home from war torn countries around the world. VTN wants to help bridge the gap to let the individuals with PTSD know that there are others going through similar experiences that can help them through what they are dealing with. They also help them acquire the tools needed to transition back into society in a way that is healthy for them and their families. This way the military vets can maintain themselves when they attempt a different career once they leave the military (VTN, 2017).

Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA)

CMHA wants to help people of all ages that are dealing with a mental illness. Each province in Canada has a provincial branch along with others in many cities. Each branch provides mental health services and programs that are most beneficial to community that it is located in. Among all of the programs and services, there are counselling sessions and groups that are provided to people struggling with PTSD (CMHA, 2017).

Centre for Addictions and Mental Health (CAMH)

CAMH like CMHA has a wide variety of mental health services. What makes them different from CMHA is they also provide services for people with addictions related to drugs, alcohol, gambling, etc. They have treatment for people with PTSD as long as they have proper medical documentation. Also CAMH gives people connection to various helplines that people with PTSD can call and have someone listen/talk to them. Not only does CAMH have support for people with PTSD, but also for the families of the individuals struggling with the illness. At CAMH they can they can better understand what their loved one is going through and find the resources that they may need (CAMH, 2012).

Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention (CASP)

It has been said that people with PTSD may be at risk of suicide. Fortunately, CASP is an organization that looks to reduce the number of suicides in Canada along with the unfortunate consequences that come about them. If you need help they can connect you with resources like 24/7 help lines and crisis centres that may be located near the individual with PTSD. They also have support for the families that have lost loved ones to suicide. It is in these support groups that the loved ones try to understand that it is not how their loved one left this world that is to be remembered, but how they lived. CASP also gives resources to anyone in Canada, so that people can be more aware of people at risk of suicide so we can get them help (CASP, 2016).

PTSD Powerpoint Presentation

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.

2. Asnis, G., Kohn, S., Henderson, M., & Brown, N. (2004). SSRIs versus Non-SSRIs in Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. Drugs, 64(4), 383-404. http://dx.doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200464040-00004

3. Bailey, C. R., Cordell, E., Sobin, S. M., & Neumeister, A. (2013). Recent progress in understanding the pathophysiology of post-traumatic stress disorder. CNS drugs, 27(3), 221-232.

4. Brady, K., Pearlstein, T., Asnis, G., Baker, D., Rothbaum, B., Sikes, C., & Farfel, G. (2000). Efficacy and Safety of Sertraline Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. JAMA, 283(14), 1837. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.14.1837

5. Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention. (2016). Need Help?: CASP . Retrieved September 22, 2017, from CASP Web site: https://suicideprevention.ca/need-help/

6. Canadian Mental Health Association. (2017). Mental Health: CMHA Ontario. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from CMHA Ontario Web site: http://ontario.cmha.ca/

7. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2012). Who We Are: CAMH. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from CAMH Web site: http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/about_camh/who_we_are/Pages/who_we_are.aspx

8. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) for Treatment of PTSD. (2017). http://www.apa.org. Retrieved 16 September 2017, from http://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/treatments/cognitive-behavioral-therapy.aspx

9. Davidson, J., Pearlstein, T., Londborg, P., Brady, K., Rothbaum, B., & Bell, J. et al. (2003). Efficacy of Sertraline in Preventing Relapse of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. FOCUS, 1(3), 273-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/foc.1.3.273

10. Dryden-Edwards, M. R. (n.d.). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: Read Up on PTSD Symptoms. Retrieved September 27, 2017, from http://www.medicinenet.com/posttraumatic_stress_disorder/article.htm

11. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy | Psychology Today. (2017). Psychologytoday.com. Retrieved 27 September 2017, from https://www.psychologytoday.com/therapy-types/eye-movement-desensitization-and-reprocessing-therapy

12. Equine Therapy for (PTSD) Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. (2017). Calico Junction New Beginnings Ranch, Inc. Retrieved 26 September 2017, from http://www.calicojunctionnewbeginningsranch.org/ptsd.html

13. Ford, J. D., Grasso, D. J., Elhai, J. D., & Courtois, C. A. (2015). Posttraumatic stress disorder: scientific and professional dimensions. Amsterdam: Academic Press. Retrieved September 23, 2017, from http://scitechconnect.elsevier.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/PTSD.pdf

14. Friedman, M. J. (2007, January 31). PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Retrieved September 27, 2017, from https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/ptsd-overview/ptsd-overview.asp

15. Hayes, J. P., VanElzakker, M. B., & Shin, L. M. (2012). Emotion and cognition interactions in PTSD: a review of neurocognitive and neuroimaging studies. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience. Retrieved September 27, 2017, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3466464/

16. Kelmendi, B., Adams, T., Yarnell, S., Southwick, S., Abdallah, C., & Krystal, J. (2016). PTSD: from neurobiology to pharmacological treatments. European Journal Of Psychotraumatology, 7(1), 31858. http://dx.doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v7.31858

17. Malia, S. The Chemistry of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). (n.d.). Retrieved September 27, 2017, from http://www.chemistryislife.com/the-chemistry-of-post-traumatic-stress-disorder

18. Masters, N. (2010). Equine Assisted Psychotherapy for Combat Veterans with PTSD (Masters of Nursing). WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY.

19. National Institute of Mental Health. (2016). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Retrieved September 24, 2017, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml#part_145372

20. Pharmacogenetics And Genomics, 19(11), 907-909. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/fpc.0b013e32833132cb

21. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. (n.d.). Retrieved September 27, 2017, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml

22. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) - Symptoms and causes. (2017). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 23 September 2017, from http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/symptoms-causes/dxc-20308550

23. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) - Treatment - NHS Choices. (2015). Nhs.uk. Retrieved 26 September 2017, from http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Post-traumatic-stress-disorder/Pages/Treatment.aspx

24. PTSD Association of Canada. (2016). Home: PTSD Association of Canada. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from PTSD Association of Canada Website: http://www.ptsdassociation.com/

25. Sadock, B.J., Sadock, V.A., & Ruiz, P. (2015). Kaplan & Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry: Behavioral sciences/clinical psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer.

26. PTSD Medications - Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) - HealthCommunities.com. (2015). Healthcommunities.com. Retrieved 24 September 2017, from http://www.healthcommunities.com/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/medications-ptsd-treatment.shtml

27. Sareen J. (2017) Posttraumatic stress disorder in adults: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. Retrieved September 23, 2017, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-in-adults-epidemiology-pathophysiology-clinical-manifestations-course-assessment-and-diagnosis#H9

28. Sari, Y. (2004). Serotonin 1B receptors: from protein to physiological function and behavior. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 28(6), 565-582.

29. Schuster, S. (2017, January 28). 19 People Describe What It's Like To Have PTSD. Retrieved September 28, 2017, from The Mighty Web site: https://themighty.com/ (Schuster, 2017) - this is for the slide with quotes at the beginning

30. Sherin, J. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: the neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 13(3), 263.

31. Shubina, I. (2015). Cognitive-behavioral Therapy of Patients with Ptsd: Literature Review. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 165, 208-216. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.624

32. Southwick, S. M., Yehuda, R., Giller Jr, E. L., & Charney, D. S. (1994). Use of tricyclics and monoamine oxidase inhibitors in the treatment of PTSD: a quantitative review. Catecholamine function in post-traumatic stress disorder: Emerging concepts, 293-305.)

33. Taber, K., & Hurley. R., (2009) PTSD and combat-related injuries: functional neuroanatomy. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. Retrieved September 27, 2017, from http://neuro.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/jnp.2009.21.1.iv

34. Three Types of Medications Used to Treat PTSD – DH Information. (2011). Dhinfo.org. Retrieved 25 September 2017, from https://www.dhinfo.org/2011/02/three-types-of-medications-used-to-treat-ptsd/

35. Veterans Transition Network. (2017). About Us: VTN Canada. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from VTN Canada Web sit: https://vtncanada.org/

36. Vieweg, W., Julius, D., Fernandez, A., Brooks, M., Hettema, J., & Pandurangi, A. (2006). Posttraumatic stress disorder: clinical features, pathophysiology, and treatment. The American Journal of Medicine. Retrieved September 22, 2017, from http://www.amjmed.com/article/S0002-9343(05)00871-5/fulltext#section.0050

37. Wilker, S., Pfeiffer, A., Kolassa, S., Elbert, T., Lingenfelder, B., Ovuga, E., Papassotiropoulos, A., de Quervain, D., Kolassa, I. (2014). The role of FKBP5 genotype in moderating long-term effectiveness of exposure-based psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Translational Psychiatry. Retrieved September 30, 2017, from http://www.nature.com/tp/journal/v4/n6/full/tp201449a.html

38. Wilson, K. (2012). Equine- Assisted Psychotherapy as an Effective Therapy in Comparison to or in Conjunction with Traditional Therapies (Undergraduate). University of Central Florida.