This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Powerpoint: asthma.pptx

Breast Cancer

INTRODUCTION

The breast is an organ that is primarily composed of adipose tissue that is found on the chest region, situated right in front of the pectoralis major muscle. The organ is found in both males and females, but have no functional purpose in males. The breast in females has a specialized function which is the production of milk for lactation. The breast anatomy is composed of 2 components the epithelial component, the lobules where milk is made, and the duct component, which connects the lobules to the external area of the nipple. In male breast anatomy, the ductal component is shunted creating blind ducts, which differentiates them from female breasts.

Breast cancer is the result of the abnormal division of breast cells within the organ. Breast cancer can be an inherited or sporadic cancer, but the most common type of genes involved are the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. The cells within the breast can create a tumor at the primary site in the breast. Breast cancer normally develops from the ductal tissues which is known as ductal carcinomas or lobular tissues which is known as lobular carcinomas. Breast cancer has a high potency of metastasizing to other nearby tissues.

Within Canada, 24,400 women and 210 men are diagnosed per year, with over 5,000 women and 60 men dying of disease. Globally, breast cancer in women accounts to 25% of all cancer cases, making it one of the largest sector of cancer in women (Boyle & Levin, 2008). Moreover, breast cancer is more common in developed countries compared to developing countries. Most cases of breast cancer are not reported because males or females refuse to report it to doctors, feminizing syndrome, or it could be simply caught too late (da Silva, 2015).

Signs & Symptoms

The five most common signs of breast cancer are as follows;

1. A new lump

-A new lump or thickening in the breast or armpit area

2. Nipple Change

-A newly inverted [pulled in] or retracted nipple

3. Skin Change

- A change in the skin of the breast, areola or nipple e.g. color, dimpling, puckering, or reddening

4. Shape Change

-A change in the breast shape or size

5. Nipple Discharge

-A discharge from the nipple that occurs without squeezing

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Blah

RISK FACTORS

SIGNS & SYMPTOMS

Blah

DIAGNOSIS

Blah

PATHOGENESIS

Blah

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Blah

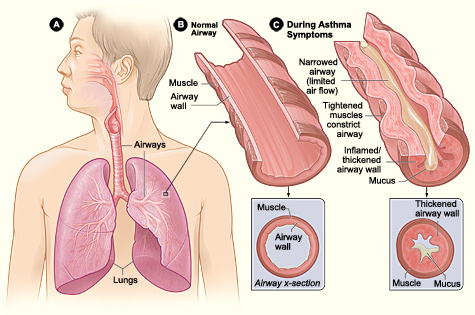

Figure 2: Difference between normal and pathophysiological bronchiole. Shows tightened muscles which constrict airway, mucus accumulation, thickened airway wall. As a result, there’s a narrow airway and limited airflow.

The Normal Physiological Response

Blah

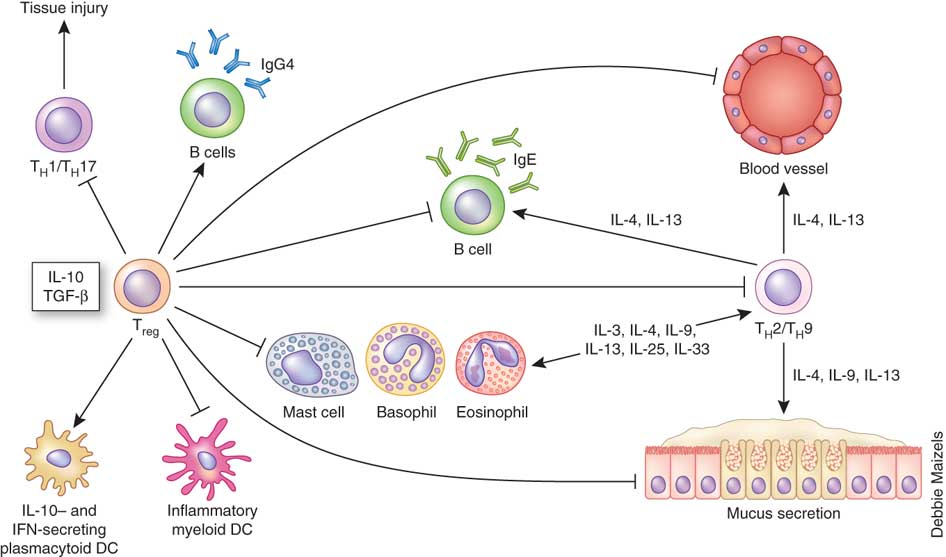

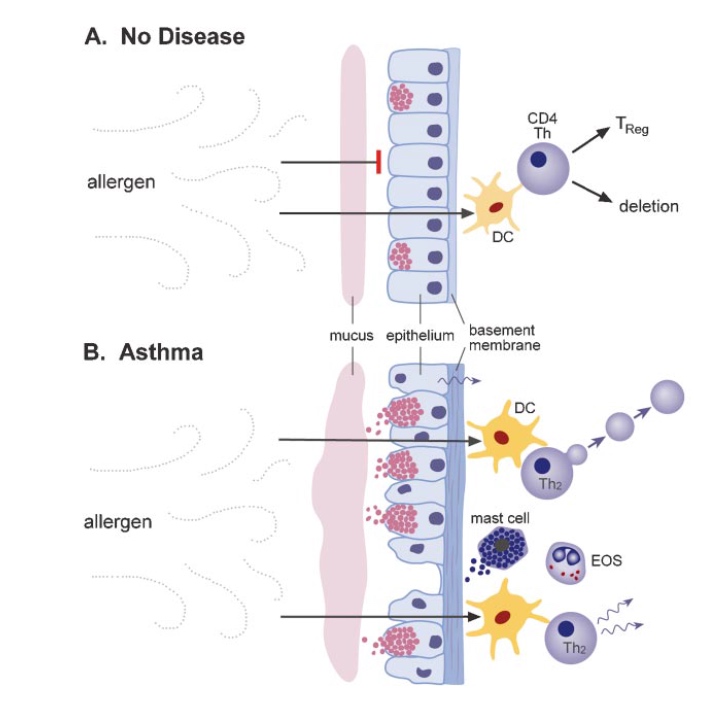

Figure 3: Flat-end arrows show the inhibitory effect of T-reg cells on B cells, dendritic cells, mast cells, basophils, eosinophils and mucus secretion during the normal response to allergens.

The Pathophysiological Asthmatic Response

Blah

The Role of Inflammatory Cells

blah

The Role of Inflammatory Mediators

1. Chemokines: important in the recruitment of inflammatory cells into airways, expressed mainly in airway epithelial cells. Eotaxin is selective for eosinophils. Thymus and activation-regulated chemokine (TARCs) and macrophage derived chemokine (MDCs) recruit T helper 2 cells (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2007).

2. Cytokines: direct, modify and determine the severity of the inflammatory response in asthma. Th2 derived cytokines include interleukin 5 which is needed for eosinophil differentiation and survival, interleukin 4 which is important for Th2 cell differentiation and interleukin 13 which is important for IgE formation. Other key cytokines include IL-1-beta and tumour necrosis factor-alpha which increase the inflammatory response, and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) which prolongs the survival of eosinophils in airways.

3. Cysteinyl-leukotrienes: potent bronchoconstrictors that are derived from mast cells. Inhibition of this mediator has been linked with an improvement in lung function and asthma symptomology (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2007). Also, studies have shown leukotriene B4 to contribute to the inflammatory response by recruiting neutrophils (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2007). IgE: important for allergic diseases and the development and persistence of inflammation. It attaches to a cell surface via a high affinity receptor. The mast cell has large numbers of IgE receptors and when activated after interacting with an antigen, there’s a release of mediators to initiate acute bronchospasm and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines to induce airway inflammation (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2007). Other cells such as basophils, dendritic cells and lymphocytes also have high affinity IgE receptors. The development of antibodies against IgE has proved that reducing IgE is effective in treating asthma (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2007).

4. IgE: important for allergic diseases and the development and persistence of inflammation. It attaches to a cell surface via a high affinity receptor. The mast cell has large numbers of IgE receptors and when activated after interacting with an antigen, there’s a release of mediators to initiate acute bronchospasm and the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines to induce airway inflammation (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2007). Other cells such as basophils, dendritic cells and lymphocytes also have high affinity IgE receptors. The development of antibodies against IgE has proved that reducing IgE is effective in treating asthma (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute 2007).

Figure 4: Difference between no disease condition. In particular, there is no mucociliary clearance and increase of T helper 2 cells in asthmatic conditions.

TREATMENTS

At its current state, there has yet to be an established permanent cure to individuals suffering from asthma. Fortunately, various management techniques are available and can be implemented in order to help alleviate the various symptoms associated with the disease. The primary suggestion asthmatic patients are recommended to do is to avoid any of the mentioned irritants involved in triggering an inflammatory response of the airway. In addition to avoiding any potential allergens, medication is available for both short-term and long-term relief. While short-term medication can provide immediate relief to counteract the constriction of the airway, long-term medication can be taken in the form of a daily supplement to aid in controlling against any future aggravation (Kuna & Kuprys, 2002).

A common short-term therapeutic can be found in the form of bronchodilators such as Ventolin. Bronchodilators are classified as beta-agonists, which seek target beta-adrenergic G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) of the bronchial smooth muscle (Kuna & Kuprys, 2002). Upon binding to these membrane-bound receptors, surrounding adenyl cyclase and ATP interact, leading to the production of cyclic-AMP (cAMP) and a subsequent cascading release into the cell. With the function of cAMP being a secondary messenger for enzyme-catalyzed processes within the cell, the relaxation of the smooth muscle cells acts further downstream in this reaction pathway (Kuna & Kuprys, 2002). Normally requiring epinephrine to produce smooth muscle relaxation, Ventolin acts as mimic to adrenaline due to both its conformation and structure, allowing it to produce the same intended result when taken by an asthmatic patient (Kuna & Kuprys, 2002). Another alternative to Ventolin is another inhaler known as Formoterol, which is better known for its more long-term viability. Taking advantage of a mechanism similar to Ventolin, the active ingredients in Formoterol allow the drug to remain at the level of the cell-membrane for an extended period of time (Pauwels et al., 1997). In addition to allowing the bronchodilation of the patient, Formoterol is also able to bind to beta2-adrenergic receptors located on the membrane of mast cells. With the binding of Formoterol to beta2-adrenergic receptors, the release of histamine, an inflammatory agent released by cells in response to any allergic response, is negatively inhibited (Pauwels et al., 1997). With the inhalation of Formoterol on a regular basis, individuals suffering from asthma will be able to relieve themselves of both bronchoconstriction and a hypersensitive response due to any irritants over a long term period.

Figure 5: Ventolin, a bronchodilator used in providing short-term relief from symptoms of asthma

A different type of medication used to treat asthma is anti-inflammatory medication. These anti-inflammatory drugs are corticosteroids such as Budesonide and alike bronchodilators, this form of drug is taken by inhalation. Budesonide reaches the target cells within one minute of inhalation and closes vascular micro leaks via vasoconstriction of the bronchi. Relaxation of the bronchial smooth muscles is experienced after 2-3 hours due to the activation of transcription factors, which increases the number of accessible beta-2 receptors (Pauwels et al., 1997). A new type of therapeutic being tested is a combination therapy involving both bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory pathways. Symbicort is a prime example of this combination medication and its use displayed that the two mechanisms have synergistic effects. Since budesonide leads to an increased number of expressed beta-2 adrenergic receptors, there are more total receptors for formoterol to bind to. In addition to this, the binding of formoterol to these beta-2 receptors increases the activity of budesonide, leading to an increased amount of anti-inflammation (Bryan et al., 2000).

Figure 6: Symbicort, used in combination drug therapy, is efficient due to the synergistic effects provided when using both bronchodilators and anti-inflammatory medication in tandem.

References

Bacharier, L. B., Boner, A., Carlsen, K. H., Eigenmann, P. A., Frischer, T., Götz, M., … & Platts‐Mills, T. (2008). Diagnosis and treatment of asthma in childhood: a PRACTALL consensus report. Allergy, 63(1), 5-34.

Bryan, S. A., Leckie, M. J., Hansel, T. T., & Barnes, P. J. (2000). Novel therapy for asthma. Expert opinion on investigational drugs, 9(1), 25-42.

Chiang, L. C., Ma, W. F., Huang, J. L., Tseng, L. F., & Hsueh, K. C. (2009). Effect of relaxation-breathing training on anxiety and asthma signs/symptoms of children with moderate-to-severe asthma: a randomized controlled trial.International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(8), 1061-1070.

Cohn L, Elias JA, Chupp GL. Asthma: mechanisms of disease persistence and progression. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004; 22: 789-815. Review

Duffy DL. (1997). Genetic epidemiology of asthma. Epidemiol Rev, 19, 129–143.

Edfors-Lubs M. (1971). Allergy in 7000 twin pairs. Acta Allergol, 26:249–285

Gold DR & Wright R. (2005). Population disparities in asthma. Annu Rev Public Health 26: 89–113.

Keller, M., Lowenstein, S. (2002). Epidemiology of Asthma. Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 23(4). 317-329.

Kuna, P., & Kuprys, I. (2002). Symbicort Turbuhaler: a new concept in asthma management. International journal of clinical practice, 56(10), 797-803.

Lambrecht, B., Hammad, H. (2015). The Immunology of Asthma. Nature Immunology, 16(1), 45-56.

Pauwels, R. A., Löfdahl, C. G., Postma, D. S., Tattersfield, A. E., O'Byrne, P., Barnes, P. J., & Ullman, A. (1997). Effect of inhaled formoterol and budesonide on exacerbations of asthma. New England Journal of Medicine, 337(20), 1405-1411.

Pawankar. (2014). Allergic diseases and asthma: a global public health concern and a call to action. World Allergy Organ J., 7(1), 12.

Potter, P. C. (2010). Current guidelines for the management of asthma in young children. Allergy, asthma & immunology research, 2(1), 1-13.

Reed, C. (2006). The natural history of asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 118( 3), 549-550.

Ronmark E, Lundback B, Jonsson EA, et al. (1997). Incidence of asthma in adults—report from the Obstructive Lung Disease in Northern Sweden study. Allergy, 52:1071–1081.

Sears, M. (2014). Trends in the Prevalence of Asthma. Chest, 145(2), 219-225.

Skloot G, Permutt S,Togins A. (1995). Airway hyperresponsiveness in asthma: a problem of limited smooth muscle relaxation with inspiration. J Clin Invest, 96, 2393–2403.

Warner JA, Jones CA, Jones AC, et al. (2000). Prenatal origins of allergic disease. J Allergy Clin Immuno. 2(2), 493–498.

Weiss ST. Diet as a risk factor for asthma. In: Chadwick D, Cardew G, eds. The Rising Trends in Asthma. New York: Wiley; 1997:244–253