Table of Contents

Postpartum Depression

Postpartum Depression PowerPoint

What is Postpartum Depression?

Postpartum depression is a mental disorder that can begin at any time during pregnancy or up until one year after child birth. It is most common for the mother of the child to develop postpartum depression, however it is also possible for the father or other partner to develop it, and is even present with adopted parents (CMHA, 2018). This mental disorder affects the way the individual feels about themselves, about others and about their new baby. More specifically, it may cause frequent thoughts about doing harm to themselves or their baby, and when left untreated, these thoughts may persist for a long time (CMHA, 2018).

Postpartum depression is a serious disorder, and should not be confused with Postpartum “baby blues” which is a much less severe and temporary condition (Mayo Clinic, 2015). Postpartum depression is extremely common and is nothing to be ashamed about, however it is important that those suffering seek counselling and support as soon as possible to prevent any harm from happening to themselves or their baby.

Signs & Symptoms

Those suffering from postpartum depression often have feelings of sadness, worthlessness, anxiousness, guilt, hopelessness and anger (CMHA, 2018). Individuals also begin to lose interest in things they once loved or once interested in. They may also withdrawal themselves from loved ones, such as family, friends and their partner (CMHA, 2018). They will also experience symptoms such as changes in diet, mainly decreased appetite and changes in sleep patterns, such as insomnia (CMHA, 2018). The most severe symptoms that occur are thoughts and feelings about harming themselves and/or their newborn baby, and may be a result of the fact that they believe they are a bad parent (CMHA, 2018).

Risk Factors

There are several risk factors associated with the development of Postpartum depression that relate to the mother, her child and other external influences. If the mother has a history of depression during her pregnancy or at other times prior to her pregnancy, she is at greater risk for postpartum depression. Other notable risk factors include the presence of bipolar disorder and postpartum depression after a previous pregnancy. Some external risk factors include family members who have had depression or other mood stability issues, difficulty breastfeeding the baby as well as health problems with the baby. Other external factors include stressful events during the last year including complications with pregnancy, illnesses or job loss. They may also include having problems in relationship with a significant other, having an unplanned or unwanted pregnancy, a lack of social support, lower socioeconomic status and even the method of childbirth (Couto, 2105).

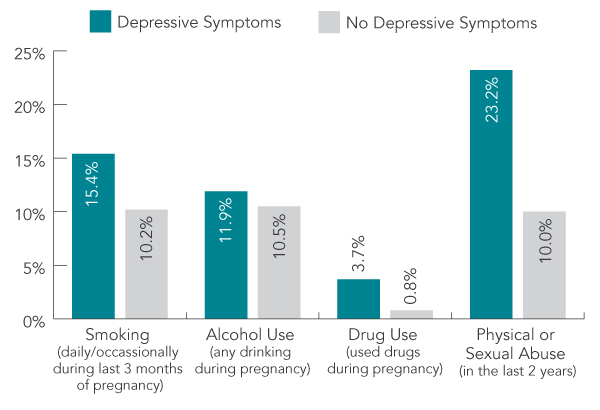

Other risk factors for Postpartum depression include the use of alcohol, the use of drugs, smoking and physical or sexual abuse. As seen in Figure 1, The Government of Canada reported the results from the Canadian Maternity Experiences Survey and found that 7.5% of women overall reported experiencing depressive symptoms during the postpartum period. Of these 7.5%, 15.4% of women smoked in the last 3 months of pregnancy, 11.9% of women used alcohol at some point during pregnancy, 3.7% of women used drugs at anytime during pregnancy and 23.2% of women experienced physical/sexual abuse in the last 2 years (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2014).

Causes of Postpartum Depression

There is no single cause of depression and thus Postpartum depression. Physical, hormonal, social, psychological and emotional factors all play a role. This is known as the biopsychosocial model of depression which is widely accepted by most researchers and clinicians. Physical changes that occur after childbirth including lack of sleep, hormonal changes in estrogen and progesterone, which drop dramatically and could contribute to postpartum depression. Other hormones such as those produced by thyroid gland may also drop dramatically and could also contribute to postpartum depression by causing the individual to feel tired, sluggish and/or depressed. Emotional changes that occur and may contribute to Postpartum depression include feeling overwhelmed and difficulty dealing with the simplest of issues. The individual might become anxious about their ability to care for a newborn. The individual might also feel less attractive and struggle with their identity or control over life (Mayo Clinic, 2015).

Genetic Causes of Postpartum Depression

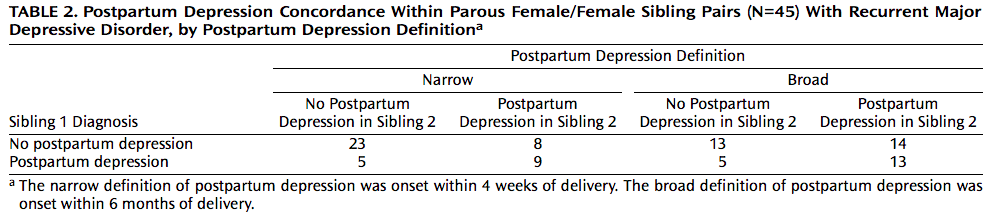

There is evidence to suggest that genetics may contribute to the development of Postpartum depression based on several studies. One study recruited 45 pairs of sisters who had unipolar depression. Several exclusion factors were considered to control for adoption, alcohol induced depression and others. The researchers observed defined narrow Postpartum depression as presentation of symptoms within four weeks of delivery and broad Postpartum depression as presentation of symptoms within 6 months of delivery. 31 women were determined to have narrowly defined PPD and 59 did not. Of the 31, 9 sisters developed PPD (29% overall but 42% on first pregnancy) and of the 59, 8 developed PPD (13% overall but 15% on first pregnancy). This relationship is depicted in Figure 2 and was determined to be significant indicating that genetics plays a role in Postpartum depression. The researchers did not find a significant difference in the broad definition of Postpartum depression (Forty et al., 2006).

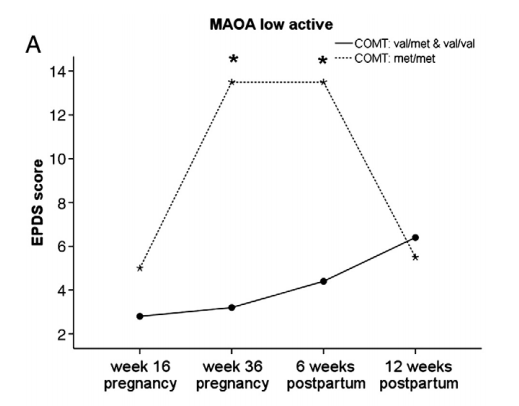

To further explore the genetic influence on Postpartum depression, researchers conducted a study involving 89 pregnant women. These women filled in two Edinburgh Postpartum Depression Scale (EPDS) questionnaires during and after pregnancy. The researchers also took blood samples and isolated DNA to analyze 5-HTT, MAO (Monoamine Oxidase) and COMT (Catechol-O-methyl transferase) polymorphisms via real time PCR. The researchers found that polymorphisms in 5-HTT, MAO and COMT interact with development of depressive symptoms. Specifically, low activity MAO increased the EPDS score, 5-HTT sl & ll polymorphism increased the EPDS score and COMT met/met polymorphism also increased the EPDS score. As seen in Figure 3, women with a combination of low active MAO and COMT the met/met polymorphism showed the greatest increase in EPDS Score (Doornbos et al., 2009). There are also several other genes that have been explored to play a role in Postpartum depression apart from the ones previously mentioned which is further evidence to support the importance of genetics.

Diagnosis

There are many ways to diagnose postpartum depression because of the varying degrees and wide array of symptoms. The first step in diagnosis is discussion between the individual experiencing symptoms and their doctor. This is to ensure that what they are experiencing is in fact postpartum depression and is not confused with postpartum baby blues or postpartum psychosis (Mayo Clinic, 2015). The individual will also fill out a depression-screening questionnaire and will have a blood test done to ensure that the symptoms they are experiencing are not due to hormone imbalance from an under-active thyroid (Mayo Clinic, 2015).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (DSM-5) is an additional tool that doctors may use in order to diagnose postpartum depression. This manual is also used by insurance companies in order to reimburse individuals for their treatment costs (Mayo Clinic, 2015).

Levels of Postpartum Depression

Postpartum Baby Blues

Postpartum depression is different from the baby blues which is the milder of the two. The baby blues is a very mild form of depression that occurs several days after childbirth with symptoms persisting no more than three to four days (Wisner, Parry & Piontek, 2002). During this period the woman experiences symptoms such as weeping, sadness, anxiety, trouble concentrating, loss of appetite and irritability. These symptoms manifest after childbirth and progresses daily peaking at four days postpartum and are usually resolved by the tenth day (Wisner, Parry & Piontek, 2002)(Beck, 2006). An important difference that distinguishes baby blues from post part depression is the fact that baby blues is a transitional period that has no negative effect on the woman’s ability to function. Additionally baby blues is considered a normal part of childbirth as an estimated 80% of new mothers are affected by this phenomenon (Wisner, Parry & Piontek, 2002)(Beck, 2006). This condition is believed to be a normal reaction to the physiological changes that occur after childbirth. Women experiencing baby blues requires emotional and physical support, not treatment (Wisner, Parry & Piontek, 2002).

Postpartum Depression

PPD easily ranks as one of the most common complication associated with childbirth. It is estimated to occur in one out of every eight women after delivery, that is roughly half a million women in the USA alone with this disorder (Sit, Rothschild and Wisner, 2006). According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the onset of postpartum depression is believed to occur within four weeks of a prior episode of depression. Scientifically however, researchers rely on the onset of postpartum depression within three months of delivery for the purpose of epidemiological studies (Sit, Rothschild and Wisner, 2006). In addition to the symptoms of baby blues women experiencing postpartum depression will display symptoms that interfere with their daily living. These include, lack of joy, sense of emotional numbness and failure, insomnia, severe mood swings. This is considered a more moderate form of depression that affects up to an estimated 10% to 13% of women after childbirth (Sit, Rothschild and Wisner, 2006).

Postpartum Psychosis

A more severe and rare form of PPD is Postpartum psychosis (PPP). Postpartum psychosis is believed to be a manifestation of bipolar disorder (Sit, Rothschild and Wisner, 2006). It is estimated to occur in one to two women per 1000 births within the first two to four weeks after childbirth. Unlike postpartum baby blues and postpartum depression, postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency that requires immediate professional treatment due to severe symptoms such as hallucinations, paranoia, delusions and self-harming thoughts that could potentially result in suicide or infanticide (Sit, Rothschild and Wisner, 2006)(Beck, 2006). As a result women with postpartum psychosis must never be left alone, they must be under supervision 24hours of the day as they are a risk to themselves and their babies (Beck, 2006). The leading cause of maternal death up to one year postpartum is suicide and the risk of suicide increases by 70% in women with PPP. The prevalence of suicide in women with PPP is 2 out of every 1000 and it has been noted that these women often result to more drastic, irreversible and extremely aggressive means such as self incineration and jumping from heights (Sit, Rothschild and Wisner, 2006). Conversely another study indicated that women without PP generally result to non-violent suicide such as overdosing. With regards to homicidal thoughts, studies have shown that 28%-35% of women hospitalised for PPP reported delusions about their infant but only 9% had thoughts of infanticide (Sit, Rothschild and Wisner, 2006). Although PPP is classified by the DSM-IV as a major form of depression, there is mounting evidence that suggests PPP is an overt presentation of bipolar disorder after delivery. This can be seen in epidemiological studies where the prevalence of PPP after childbirth is 72%-88% for mothers with bipolar disorder and 12% for mothers with schizophrenia (Sit, Rothschild and Wisner, 2006). Epidemiological studies have calculated the mean age of onset of PP to be 26.3 years, a time when most women have undergone their first or second childbirth (Sit, Rothschild and Wisner, 2006).

Prevention of Postpartum Depression

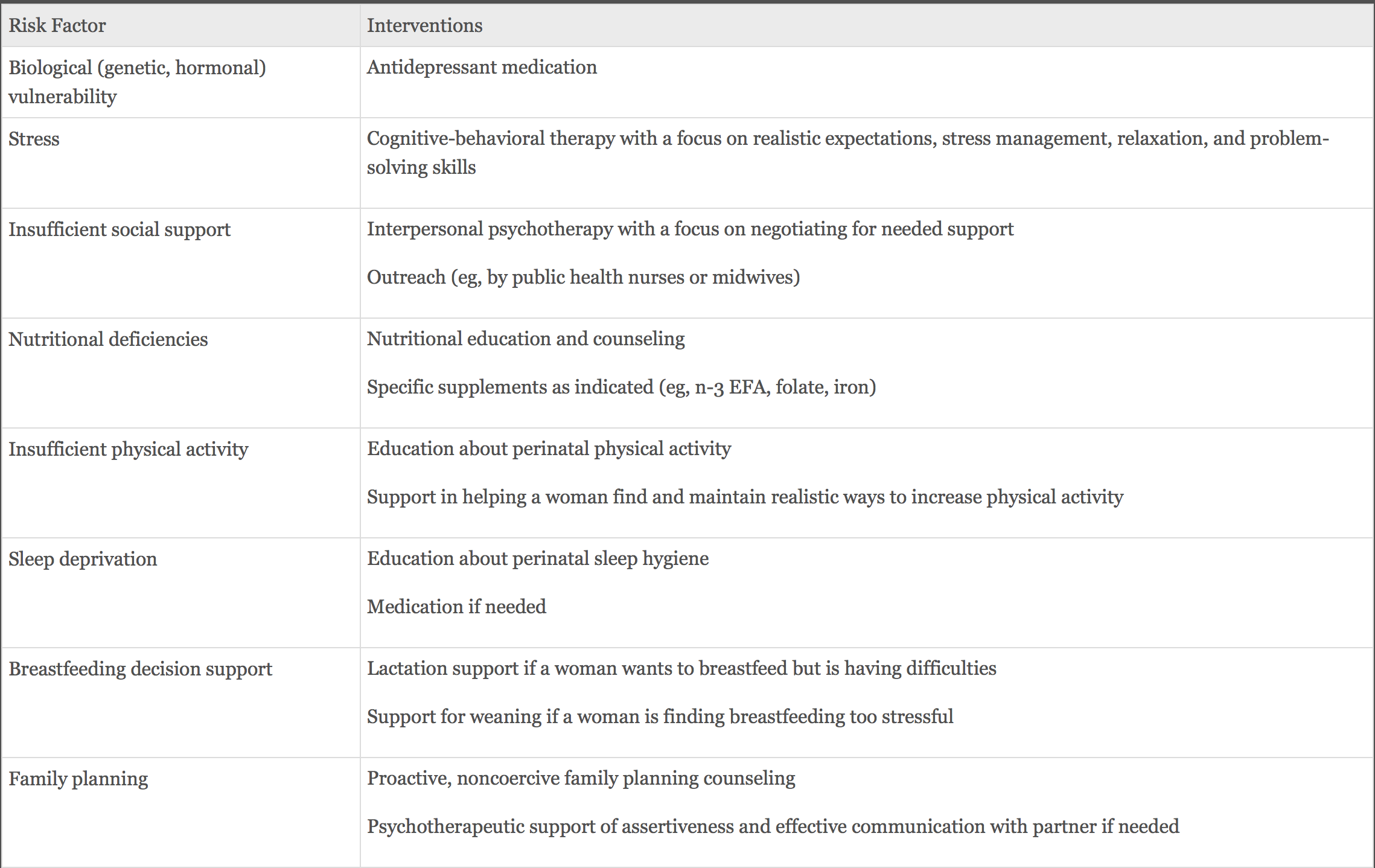

The consequences of postpartum depression can be devastating. Suicide and infanticide discussed earlier are not the only consequences of untreated postpartum depression and the mother does not bear these consequences alone. The offspring also suffers adverse effects such as emotional regulation and stress reactivity etc. as a result of postpartum depression (Miller & LaRusso, 2011). Studies have showed the apparent effect of PPD during infancy which continue to persist through adolescence and even adulthood. Given the lack of scientific knowledge on PPD it is understandably difficult to formulate preventative measures. However certain risk factors discussed in this wiki and presented in Figure 4, have been shown to display a positive correlation with increased risk of developing PPD. Therefore it follows that improving one or more of these areas could serve as primary prevention by reducing vulnerability to PPD, secondary prevention by reducing severity, duration and symptoms of PPD, and finally tertiary prevention by improving relationships and prognosis for women and their offspring (Miller & LaRusso, 2011). One such approach to the prevention of PPD is the identification of the optimal protective factors for a healthy woman and crafting an individual plan to enable each PPD patient conform to this ideal profile (Miller & LaRusso, 2011). The optimal protective factors have been shown to include protection from the effects of abrupt hormonal flux, practising of a healthy diet, high ability to manage stress, availability of social support, breastfeeding, exercise and a host of other factors (Miller & LaRusso, 2011). Preventative strategies can then be formulated for an individual depending on which of the above factors they require or need to strengthen. Those strategies can be either psychological and psychosocial (Interpersonal Psychotherapy and Postnatal Psychological Debriefing) or biological and pharmacological (Estrogen Therapy and Calcium Supplementation).

Pharmacological and Biological Prevention

- Estrogen Therapy

An open trial study by Sichel et al in the USA studied 11 women, 7 with a history of PPP and 4 with a history of PPD. In this study all 11 participants were consistently administered with hight dosage of oral estrogen immediately after childbirth (Dennis, 2004). It is important to note that although all participants had a history of depression, all were for all intents and purposes well for the duration of this pregnancy. Over four weeks the researchers orally administered premarin to the participants with a daily decreasing dosage. However in the first few days after labour the researchers mimicked the natural levels of estradiol levels by administering high dosages that were then gradually tapered off (Dennis, 2004). The participants were evaluated for mood and depressive symptoms during the first 5 days postpartum using the DSM-III-R checklist. A follow up in the form of a clinical interview was conducted postpartum at 1, 3, 6 and 12 months. During this 1 yr follow up all but one participant developed PPD (Dennis, 2004). The results of this study looks promising and should be investigated more.

- Calcium Supplementation.

Evidence for dietary calcium as a potential preventative measure for PPD stems from studies conducted on its effect on premenstrual syndrome (PMS) (Dennis, 2004). A low level of total and ionised calcium were observed at the midpoint of menstrual cycle by one of these studies. This low level of total and ionised calcium was then proven to correlate with an increased level of estradiol (Dennis, 2004). The study concluded that there was a statistical significant difference in the level of total serum calcium across both the women with PMS and the control group. This data suggests that the menstrual cycle plays a key role in calcium metabolism and it indicates the possibility that the reduction of calcium metabolism in women as a result of PMS is further exacerbated by the constant flux of hormones (Dennis, 2004). To modify the above for PPD a study was conducted in the USA, specifically, Portland, Oregon, and Albuquerque, New Mexico. This randomised control trial (RCT) sought to prevent pre-eclampsia, and participants were evaluated using the EPDS scale are 6 and 12 weeks postpartum. EPDS scores greater than 14 was registered in 11% of the experimental calcium group and 18% for the placebo group from Portland at 6 weeks (Dennis, 2004). Albuquerque on the other hand observed 24% for the experimental and 21% for the placebo (P>0.05). At 12 weeks an EPDS score of >14 was reported by 5.7% of the calcium group compared with 15.3% of the placebo group (P>0.01) (Dennis, 2004). These results serves as evidence of the significant reduction of point prevalence of PPD at 12 weeks and marginally at 6 weeks by calcium supplementation.

Psychosocial and Psychological Prevention

- Interpersonal Psychotherapy

IPT as a short term prevention is a psychotherapy that aims to rectify present psychological issues while emphasising the interpersonal context in which depressive symptoms arise (Werner, Miller, Osborne, Kuzava & Monk, 2014). IPT was first originally developed as a treatment for Major Depressive Disorder but has since been adapted to function as a preventative measure for PPD for pregnant women. To date three of seven studies on the efficacy of IPT in the prevention of PPD have incorporated the ROSE program (Reach Out, Stay strong, Essentials for new mothers) (Werner, Miller, Osborne, Kuzava & Monk, 2014). The ROSE program developed by Zlotnick is a brief group intervention based on IPT with the aim of helping pregnant women on public assistance overcome the risk factors of PPD (Figure 4). It consists of 4 weekly 1 hour group meetings during pregnancy. In a study by Zlotnick incorporating the ROSE program, 35 women who had previously reported at least one risk factor for PPD (Figure 4) were randomised into experimental and control group. All participants in this study were required to enrol in standard antenatal care but only the experimental group were participants of the ROSE program (Werner, Miller, Osborne, Kuzava & Monk, 2014). 33% of the control group compared to none of the experimental group had developed PPD as measured by the DSM-IV. Whatsmore, there was a significant reduction in the BDI scores of the ROSE program participants compared to that of the control group (p<.001) (Werner, Miller, Osborne, Kuzava & Monk, 2014). A second study by Zloknick with the same conditions as the above study and an increased sample population of 99 women between 23 to 32 weeks pregnant reported similar results. In that study 4% of women in the intervention group developed PPD as opposed to 20% of women in the control group (p=0.04) (Werner, Miller, Osborne, Kuzava & Monk, 2014). In summary all seven studies with IPT as a preventative measure consistently demonstrated a reduced risk of PPD. Finally some of the above studies utilised untrained non-clinical staff, which suggests the possibility of a wider application.

- Postnatal Psychological Debriefing

Psychological debriefing consist of semi-structured psychological interview in which a person’s traumatic event is explored with the aim of reducing psychological stress, in the postnatal setting this takes the form of a discussion of a mother’s concerns about labour and motherhood (Werner, Miller, Osborne, Kuzava & Monk, 2014). Two of the five RCTs exploring the efficacy of postnatal psychological debriefing in the prevention of PPD showed positive results. One such study is that conducted by Lavender and Walkinshaw (1998), in which some 120 British women with normal at-term vaginal deliveries were studied. Subjects were randomised without prior screening for antenatal depression to either receive a single debriefing session by an untrained midwife before discharge or to continue treatment as normal. This single debriefing session involved an “interactive interview” in which the interview spent the necessary time exploring their feelings and experience of labor (Werner, Miller, Osborne, Kuzava & Monk, 2014). All participants were subsequently mailed a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) questionnaire 3 weeks after discharged and these questionnaires were scored using the HADS scale ranging from 0 to 21. Results showed a significantly decreased likelihood of developing high depression and anxiety (defined as a depression or anxiety score >10 points, p<0.0001 and p<0.001 respectively) three weeks postpartum (Werner, Miller, Osborne, Kuzava & Monk, 2014).

Treatment

The treatment of postpartum depression is still being developed as researchers continue to investigate methods of intervention for this mental health issue. Currently there are two main categories for the available courses of treatment for postpartum depression: pharmacological and psychological.

Pharmacological Treatment of Postpartum Depression

Based on the premise that postpartum depression presents in many similar ways to other depressive disorders, such as major depressive disorder, physicians have been using very similar courses of action to alleviate symptoms of postpartum depression and prevent relapse of the depressive state. One of the main courses of treatment of postpartum depression is pharmaceuticals such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizers. These pharmaceutical drugs can have varying levels of effectiveness depending on the person and whether they are taking other medications to treat postpartum depression or another unrelated disease or disorder.

Antidepressants

There are different classes of antidepressants used to treat postpartum depression either individually or taken in conjunction with other antidepressant, antipsychotic or mood stabilizing medications. Antidepressants can be categorized into six classes of drugs, listed here from most commonly prescribed to least commonly prescribed:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): SSRIs include common antidepressants such as Prozac (fluoxetine) and Zoloft (sertraline). Due to their milder side effects, these drugs are most commonly prescribed for the treatment of anxiety and depression. However, they may still result in nausea, diarrhea, vomiting, difficulty sleeping, and lower sex drive (CAMH, 2018).

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): SNRIs include drugs such as Effexor (venlafaxine) and Pristiq (desvenlafaxine) and are also used in the treatment of anxiety and depression, along with chronic pain. The side effects of SNRIs are typically nausea, dizziness, tiredness, and loss of appetite and sexual drive (CAMH, 2018).

- Norepinephrine and dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs): This class of drugs includes medications like Wellbutrin and Zyban (both bupropion drugs). NDRIs typically have the ability to treat depression in conjunction with other antidepressants and provides the patient with more energy. Some side effects of NDRIs are insomnia and jittery behaviour. NDRIs can also be used to treat ADD/ADHD and help patients who smoke to quit (CAMH, 2018).

- Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs): NaSSAs are the most sedating antidepressants and include drugs like Remeron (Mirtazapine). Physicians typically prescribe this class of antidepressants to patients experiencing severe anxiety or insomnia, and can also be used to stimulate appetite. The common side effects of NaSSAs include weight gain and drowsiness (CAMH, 2018).

- Cyclics: This group of antidepressants is an older class of drugs and includes Ludiomil (maprotiline), Elavil (amitriptyline) and Tofranil (imipramine). Typically, these are not the first class of antidepressant to be prescribed by a physician due to the increased amount of side effects in comparison to the other classes. Some of these side effects include constipation, sedation, blurry vision, dizziness, weight gain, difficulty urinating, and tremors (CAMH, 2018). They may also cause heart arrhythmias, which is why it is recommended for prescribing physicians to conduct an electrocardiogram (ECG) before beginning this specific drug treatment (CAMH, 2018). However, if patients do not get relief from severe depression with other classes of antidepressants, cyclics may help.

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs): Nardil (phenelzine) and Parnate (tranylcypromine) are two of the types of MAOIs available. MAOIs were the first class of antidepressants discovered, and though they may be effective, they must be taken on a strict diet which is why they are not as commonly prescribed. Other newer MAOIs do not require dietary restrictions, however, they are not as effective. Some common side effects include insomnia, orthostatic hypotension (BP changes when patient moves from sitting to standing), and weight gain (CAMH, 2018).

Estrogen Hormone Therapy

During pregnancy and postpartum, there are dramatic changes in hormone levels occurring. One notable change in maternal levels of estrogen and progesterone occurs at the time of

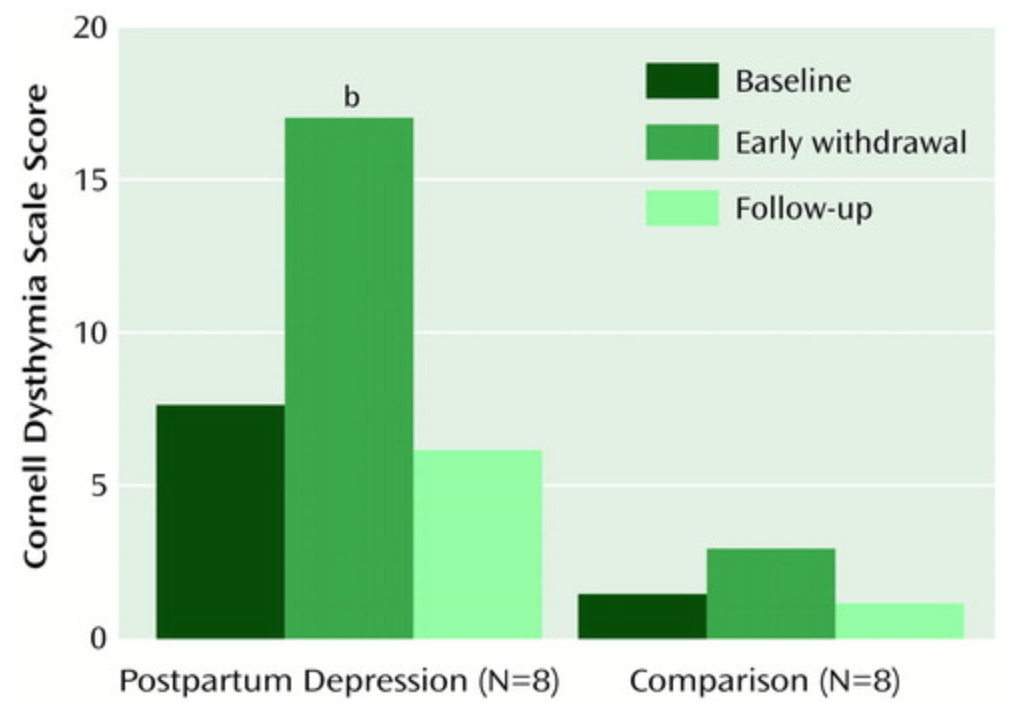

Figure 5 : Observed patient scores on the Cornell Dysthymia Rating Scale prior to and following estrogen and progesterone replacement was administered in 8 women with a history of PPD and 8 without a history of PPD. A significant different was observed between baseline and withdrawal periods in women with a history of PPD. Modified from Bloch et al. (2000).

delivery. This significant drop in estrogen and progesterone has been proposed as a potential trigger for the onset of postpartum depression (Moses-Kolko et al., 2009). This discovery led to the hypothesis that estradiol could be used as a potential hormone therapy for women suffering from postpartum depression. Estradiol functions similarly to other psychotropic drugs, however, there is not yet sufficient evidence to determine if it a suitable treatment for postpartum depression (Bloch et al., 2000; Moses-Kolko et al., 2009). While more conventional pharmacological antidepressant treatments can be very effective for treating postpartum depression, a natural alternative may be preferred, especially by women who breastfeed their infants.

The treatment of postpartum depression with synthetic forms of naturally occurring estrogen is appealing due to the estrogen withdrawal that occurs at parturition. A study published in American Journal of Psychiatry in 2000 determined that women with a prior history of postpartum depression experienced mood symptoms following exposure to declining levels of estradiol (an estrogen steroid hormone) and progesterone, meanwhile women that did not have a history of postpartum depression did not experience these mood symptoms (Bloch et al., 2000).

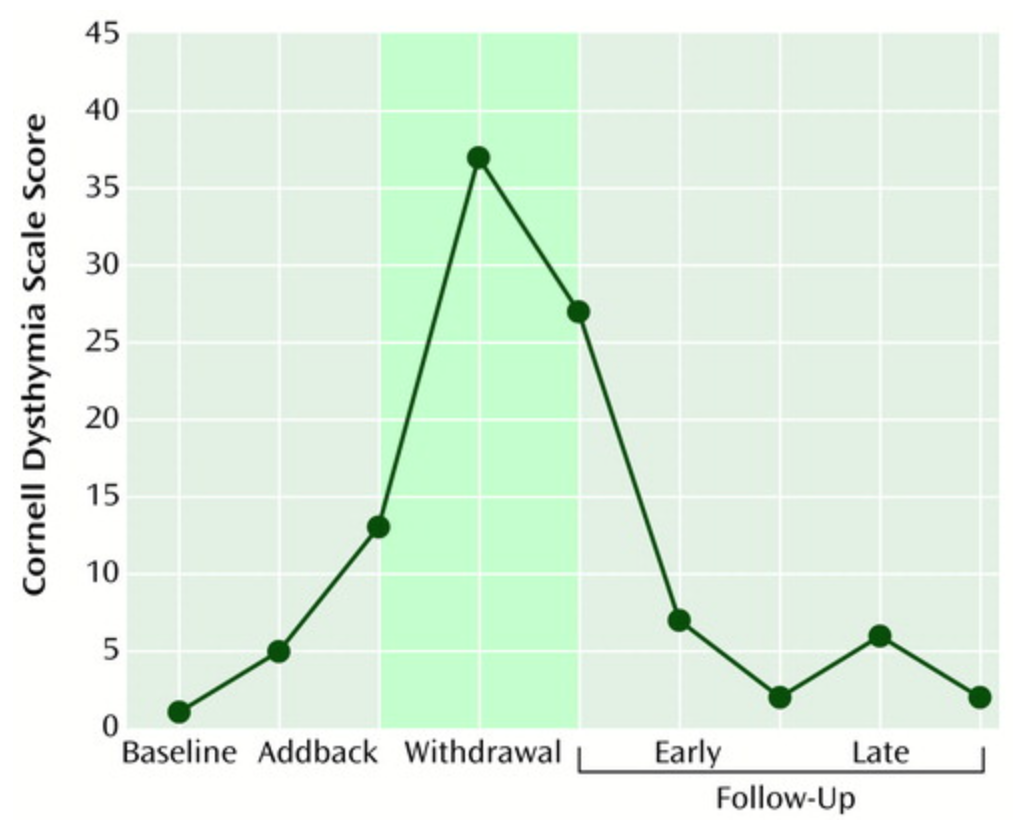

In the study conducted by Bloch et al. (2000), women aged 22 to 45 one year postpartum were divided

Figure 6 : Mean patient scores of 8 women with a history of PPD using the Cornell Dysthymia Rating Scale after the Addback phase (active medication was being administered) and following the Withdrawal phase (placebo medication was administered). These results best exhibit the typical mood shift observed in women with a history of PPD. Modified from Bloch et al. (2000).

into two separate groups based on whether they had a history of postpartum depression in previous pregnancies. For two months, baseline measurements were taken with participants providing Cornell Dysthymia Scale ratings. The Cornell Dysthymia Scale is a 20-item questionnaire created to improve upon the commonly-used Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS) in assessing the symptoms of dysthymia, a form of chronic depression. Next, participants received 1 monthly injection for 5 months of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analog (leuprolide acetate, 3.75/month) to produce a stable hypogonadal condition.

During the baseline phase, concurrently received either placebo or active medication (increasing amounts of estradiol and progesterone: 4mg/day of estradiol to 10mg/day of estradiol by the end of the trial; 400mg/day of progesterone to 900mg/day of progesterone by the end of the trial). During the withdrawal and follow up phases, active medications were replaced with placebo medications and the control patients continued to take placebo medications. This induced the dramatic drop in estradiol and progesterone seen in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Associated Fetal and Maternal Risk

In addition to the side effects caused by antidepressants, antipsychotics, and mood stabilizing medication, one main concern mothers have with regards to pharmacological intervention is the risk it poses to the newborn child. The baby can be exposed to the medication the mother is currently taking through breastfeeding (CAMH, 2018; Fitelson et al., 2010). The amount of medication passed through the breast milk is very small and generally not considered by doctors to be a great risk for to the health and development of the baby, especially considering how the benefits of breastfeeding (reduced allergy risk, enhanced natural immunity, bonding with mother) outweigh this risk (Fitelson et al., 2010). In terms of hormone therapy, some known adverse effects are the risk of interfering with lactation, an increased risk of endometrial cancer, and endometrial hyperplasia (an increase in the amount of tissue caused by cell proliferation in the endometrium) (Fitelson et al., 2010). For many women, the potential risk to the newborn child often associated with pharmaceutical interventions and the experimental nature of hormone therapy leads them to consider other treatment options like psychological treatment.

Psychological Treatment of Postpartum Depression

In addition to pharmacological and hormonal interventions for women experiencing postpartum depression, psychosocial or psychological interventions have also been commonly used as forms of therapy for this mood disorder. Although these treatments are preferred by patients with PPD as it has no effect on the health of the newborn infant, it is also of great concern that this treatment is not always available due to the incurred costs from therapy. Furthermore, more research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these forms of treatment, specifically in PPD populations as most of the evidence is currently taken from studies conducted with major depressive disorder populations. There are four principle types of psychological treatments for postpartum depression: Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), Interpersonal Therapy (IPT), Nondirective Counselling and Peer and Partner Support.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT)

CBT is the most common treatment for postpartum depression. Normally the first intervention method recommended by physicians, it can alleviate postpartum depressive symptoms that range from mild to moderate in nature (Fitelson et al., 2010). The primary focus of this therapy is to teach patients to understand how their thoughts, feelings and behaviours can work together and can inform and influence one another (CAMH, 2018). The ultimate goal with this therapeutic treatment is to help depressed patients to change patterns of negative thinking and behaviour to enhance coping and reduce stress (Fitelson et al., 2010; CAMH, 2018).

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT)

IPT has a primary focus of rebuilding and working on relationships and the connection between interpersonal problems and their effect on mood. The benefits of this particular therapy include helping patients adjust to the changing roles and dynamics in their relationships and building better social supports (Fitelson et al., 2010). Patients and physicians choose to target one of the four interpersonal problem categories as a particular focus for their treatment. These four categories are role transition, role dispute, grief, and interpersonal deficits (CAMH, 2018). Specific problem areas for people suffering from PPD include the relationship between mother and infant, mother and partner, as well as the transition back to the workforce following maternity leave.

Nondirective Counselling

Nondirective counselling (also known as person-centred therapy) is a specific type of counselling that stresses and promotes nonjudgmental and empathetic listening and support (Fitelson et al., 2010). This particular therapy is notably less structured than CBT and IPT. The primary goal of this therapy is to ensure that the patient is provided with a safe space to express any and all concerns relevant to motherhood, postpartum depression, and the emotional strain that can result from these concerns (Fitelson et al., 2010).

Peer and Partner Support

Peer and partner support is a therapy that is built around the finding that inadequate social support is an identified risk factor for developing postpartum depression. The main focus of this therapy is to either reduce the risk of postpartum depression prior to parturition, or to alleviate postpartum depressive symptoms by increasing the number of new social supports available to the patient and to strengthen previously established social supports (Fitelson et al., 2010).

Alternative Treatments of Postpartum Depression

- Electroconvulsive Therapy: This particular therapy is only ever recommended in severe cases (such as postpartum psychosis) and when the patient does not respond to other treatments (Fitelson et al., 2010; Mayo Clinic, 2017). During ECT, a small amount of electrical current is applied to your brain to produce brain waves similar to those that occur during a seizure (Fitelson et al., 2010). The chemical changes triggered by the electrical currents can reduce the symptoms of psychosis and depression. This treatment is also used with major depressive disorder (Fitelson et al., 2010).

- Bright Light Therapy: This therapy was originally conceived for seasonal affective disorder, but can also be used for non-seasonal depression, like postpartum depression (Fitelson et al., 2010). This is also an attractive option for postpartum depression treatment since this poses no risks to the fetus or nursing infant or the mother; it can be done at home; and it is low cost. During light therapy, the patient sits or works near a device called a Light Therapy Box. The Light Therapy Box will emit a bright light that mimics natural outdoor light. It is thought that the artificial natural light can affect brain chemicals linked to mood and sleep (Mayo Clinic, 2017). Most of the research conducted on bright light therapy has been conducted on seasonal affective disorder populations, not postpartum depression populations; therefore, more research is necessary to determine its effectiveness in treating PPD.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids: Aside from the known benefits of omega-3 fatty acids during pregnancy for the mother and the foetus, it has also been shown to positively affect mood (Fitelson et al., 2010). However, this particular effect of omega-3 fatty acids has not been substantiated by sufficient research.

- Acupuncture and Massage: Acupuncture is the ancient Chinese tradition of the inserting and manipulating needles into various points on the body to treat and relieve pain. The use of acupuncture and massage mainly aims to alleviate stress, a known contributor to postpartum depressive symptoms. To determine the effectiveness of this treatment, more research is required.

- Exercise: Due to the release of endorphins that occurs during exercise, it is thought that this could help alleviate symptoms of postpartum depression. However, once again, there is not sufficient research to substantiate these findings specifically in postpartum depression populations.

Prevalence of Postpartum Depression

Worldwide

Based on a meta-analysis conducted by Gelaye B et al. (2016), the pooled prevalence of postpartum depression (PPD) in women from low-and-middle-income (LAMIC) countries worldwide is estimated to be 19%. The meta-analysis included 53 studies published between 1998 and 2015. The data collected from these studies represented 23 LAMIC countries and a total of 38,142 participants. Of the 53 studies, 7 studies were from Brazil, 6 from Turkey, 4 from India, 4 from Thailand, 4 from China, 3 from Mexico, 3 from Nigeria, 3 from Iran and the rest (1 or 2 studies) from other LAMICs (Armenia, Ghana, Jordan, Lebanon, Malaysia, Mongolia, Morocco, Nepal, Pakistan, Peru, South Africa, Tunisia, Uganda, Vietnam and Zimbabwe). Sample sizes ranged from 41 in Thailand to 13,360 in Ghana.

Figure 7 shows a subset of the studies analyzed and the associated prevalence of PPD (%), as well as the scale used to measure PPD. While there was significant heterogeneity observed between studies, the highest prevalence of PPD was seen in India (48.5%) and the lowest prevalence of PPD was observed in Ghana (3.8%). PPD was predominantly measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). The EPDS is a 10-item, self-reported scale that includes questions such as “I have felt scared or panicky for no good reason,” “I look forward with enjoyment to things,” and “The thought of harming myself has occurred to me.” Other scales utilized to measure PPD included the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID).

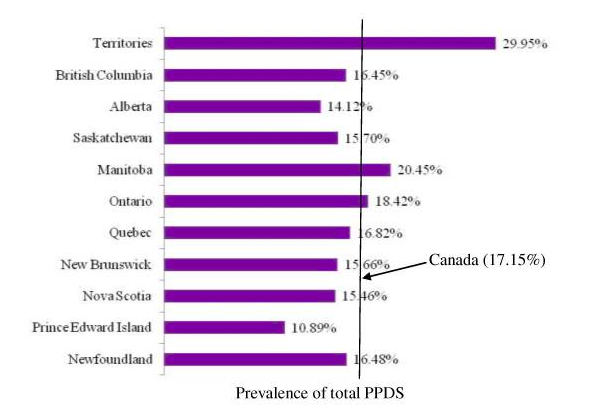

Canada

A study conducted by Lanes A et al. (2011) estimated the overall prevalence of minor and minor/major Postpartum Depressive Symptomatology (PPDS) in Canadian women to be 17.15%, with the highest prevalence of PPDS in the Territories (29.95%) and the lowest prevalence of PPDS in Prince Edward Island (10.89%; Figure 8). PPDS was measured using the EPSD, where a score of 0-9 indicated no risk of experiencing symptoms of PPD, a score of 10-12 indicated a minor/major risk, and a score of 13 or more indicated a major risk of experiencing PPD symptoms.

A total of 6,421 Canadian women from 10 provinces and 3 Territories were included in the study. These women had a live birth between 2005 and 2006 as well as previously completed the Maternity Experience Survey (MES), a nationwide survey conducted by Statistics Canada between 2006 and 2007 to assess pregnancy, delivery, and postnatal experiences of mothers and their children.

United States of America

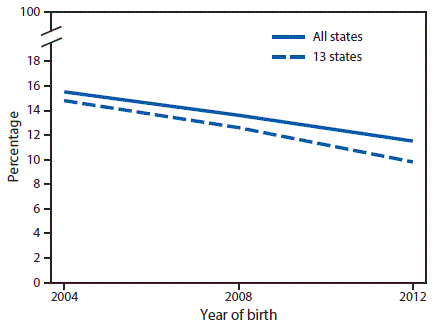

The prevalence of PPD in the USA was calculated by Ko LY et al. (2017) using self-reported data collected from 27 US States participating in the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS). PRAMS is an ongoing, population-based surveillance system that collects state-specific data on maternal attitudes and experiences before, during, and after pregnancy (CDC, 2018). Questions are based on attitudes and feelings about a woman's most current pregnancy, maternal alcohol and tobacco consumption, physical abuse before and during pregnancy, infant health care, and mother's knowledge of pregnancy-related health issues, among other topics (CDC, 2018).

The PRAMS data indicated an overall incidence of postpartum depressive symptoms (PDS) in 11.5% of women in 2012. In 13 of the states participating in PRAMS, there was a decline in PDS from 14.8% in 2004 to 9.8% in 2012 (Figure 9). PDS was found to be highest in mothers who had less than 12 years of education, were unmarried, were postpartum smokers, had greater than or equal to 3 stressful life events in a year before birth of the child, and had a child of abnormally low birthweight or that had to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU).

PPD in Men

Although PPD is most commonly reported by mothers, it can affect any new parent, including fathers (CMHA, 2018). For example, a study conducted by Suto M et al. (2016) reported that 17% of Japanese men from a total sample of 215 fathers experienced symptoms of depression in the first 3 months after birth of their child. Symptoms of PPD were self-reported by fathers at 6 different time points (once during pregnancy and 5 times during the first 3 months after the baby's birth) using the EPDS. It was found that the father's history of psychiatric treatment and depressive symptoms during the pregnancy were significantly correlated with paternal depressive symptoms in the postpartum period.

A separate study conducted by Massoudi P et al. (2016) looked at a population-based sample of 885 Swedish couples and found that 6.3% of fathers had reported symptoms of depression at 3 months postpartum. The data was self-reported by fathers using multiple questionnaires at 3 months postpartum. Specific measures that were collected included depressive symptoms (EPDS), sociodemographic factors, time at home since birth of child, work time since birth of child, partner relationship and support from partner (Swedish parental stress questionnaire), history of depression, and stressful life events. Out of all these measures, problems in partner relationship, low education level, previous history of depression, stressful life events, and low partner support were significantly correlated with reports of PPD.

What can you do to help?

In conclusion, PPD is a difficult experience for everyone, including partners, friends, and family members. Most people expect the arrival of a new baby to be a happy and joyful time, and PPD can drastically change this. Overcoming PPD is challenging, but it can be done with the right support and encouragement from loved ones. PPD is no one's fault and everyone plays a huge role in recovery (APA, 2018; CMHA, 2018).

If you have a loved one who is affected by PPD, you can help by:

- Having realistic expectations of your loved one's day-to-day abilities and experiences

- Offering help with daily responsibilities, chores, and child care (especially nighttime feedings) so that your loved one does not feel overwhelmed and has time to rest

- Accompanying them to doctor's appointments or support groups

- Being supportive and encouraging of your loved one's progress by letting them know you are there for them

- Seeking support for yourself if needed (For examples, support groups for family members of individuals with PPD)

References

- American Psychological Association (APA). (2018). Postpartum Depression. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pi/women/resources/reports/postpartum-depression.aspx

- Beck, C. T. (2006). Postpartum Depression: It isn’t just the blues. AJN The American Journal of Nursing, 106(5), 40-50.

- Bloch, M., Schmidt, P. J., Danaceau, M., Murphy, J., Nieman, L., & Rubinow, D. R. (2000). Effects of gonadal steroids in women with a history of postpartum depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157(6), 924–930. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.924

- Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA). (2018). Postpartum Depression. Retrieved from https://cmha.ca/documents/postpartum-depression

- Case reports on Pharmacology | Global Events | USA| Europe | Middle East| Asia Pacific. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://casereports.alliedacademies.com/events-list/case-reports-on-pharmacology

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). PRAMS Questionnaires. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/prams/questionnaire.htm

- Couto, T. C. (2015). Postpartum depression: A systematic review of the genetics involved. World Journal of Psychiatry, 5(1), 103. doi:10.5498/wjp.v5.i1.103

- Dennis, C. (2004). Preventing Postpartum Depression Part I: A Review of Biological Interventions. The Canadian Journal Of Psychiatry, 49(7), 467-475. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/070674370404900708

- Doornbos, B., Dijck-Brouwer, D. J., Kema, I. P., Tanke, M. A., Van Goor, S. A., Muskiet, F. A., & Korf, J. (2009). The development of peripartum depressive symptoms is associated with gene polymorphisms of MAOA, 5-HTT and COMT. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 33(7), 1250-1254. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.07.013

- Fitelson, E., Kim, S., Baker, A. S., & Leight, K. (2010). Treatment of postpartum depression: clinical, psychological and pharmacological options. International Journal of Women’s Health, 3, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S6938

- Forty, L., Jones, L., Macgregor, S., Caesar, S., Cooper, C., Hough, A., … Jones, I. (2006). Familiality of Postpartum Depression in Unipolar Disorder: Results of a Family Study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(9), 1549-1553. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.9.1549

- Gelaye, B., Rondon, M., Araya, R. & Williams, M.A. (2016). Epidemiology of maternal depression, risk factors, and child outcomes in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry, 3(10), 973-982. Doi: https://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2FS2215-0366(16)30284-X

- Ko, J.Y., Rockhill, K.M., Tong, V.T., Morrow, B. & Farr, S.L. (2017). Trends in Postpartum Depressive Symptoms — 27 States, 2004, 2008, and 2012. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), 66(6), 153-158. Doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6606a1

- Lanes, A., Kuk, J.L. & Tamim, H. (2011). Prevalence and characteristics of Postpartum Depression symptomatology among Canadian women: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 11, 302. Doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-302

- Massoudi, P., Hwang, C.P. & Wickberg, B. (2016). Fathers’ depressive symptoms in the postnatal period: Prevalence and correlates in a population-based Swedish study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 44(7), 688-694. Doi: 10.1177/1403494816661652

- Mayo Clinic. (2015, August 11). Postpartum depression - Symptoms and causes. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/postpartum-depression/symptoms-causes/syc-20376617

- Mayo Clinic. (2017, August 9). Light therapy. Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/light-therapy/about/pac-20384604

- Miller, L., & LaRusso, E. (2011). Preventing Postpartum Depression. Psychiatric Clinics Of North America, 34(1), 53-65. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2010.11.010

- Moses-Kolko, E. L., Berga, S. L., Kalro, B., Sit, D. K. Y., & Wisner, K. L. (2009). Transdermal estradiol for postpartum depression: A promising treatment option. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology, 52(3), 516–529. https://doi.org/10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181b5a395

- Sit, D., Rothschild, A. J., & Wisner, K. L. (2006). A review of postpartum psychosis. Journal of women's health, 15(4), 352-368.

- Suto, M., Isogai, E., Mizutani, F., Kakee, N., Misago, C. & Takehara, K. (2016). Prevalence and Factors Associated With Postpartum Depression in Fathers: A Regional, Longitudinal Study in Japan. Research in Nursing and Health, 39(4), 253-262. Doi: 10.1002/nur.21728

- Werner, E., Miller, M., Osborne, L., Kuzava, S., & Monk, C. (2014). Preventing postpartum depression: review and recommendations. Archives Of Women's Mental Health, 18(1), 41-60. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0475-y

- Wisner, K., Parry, B., & Piontek, C. (2002). Postpartum Depression. New England Journal Of Medicine, 347(3), 194-199. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/nejmcp011542