Table of Contents

Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD)

PDF Presentation: d-lysergic_acid_diethylamide_lsd_.pdf

PowerPoint Presentation: d-lysergic_acid_diethylamide_lsd_.pptx

Introduction

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), also known commonly as “L” or “Acid”, is a psychedelic, hallucinogenic, and recreational drug that alters cognition and perception (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). This leads to changes in awareness, perceptions, feelings along with seeing/feeling sensations and images that are not truly present (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). LSD is most commonly taken as a dissolving stamp on the tongue, but can also be taken as a gel, liquid, cube, gelatin or injection. 89% of LSD users only take the drug once and as a whole LSD usage has decreased greatly since its peak in the 1950's and 1960's (Krebs & Johansen, 2013). Under LSD a wide range of symptoms and effects can potentially occur including some parts of the brain being more connected while otherparts becoming less connected (Das et al., 2016). Symptoms vary depending on the individual and the amount taken LSD taken (NIDA, 2016). LSD is not physically addictive but can be psychologically considered depending on the amount of LCD taken in a lifetime (Das et al., 2016). Only about 20–30 micrograms of LSD is required for a reaction to occur in the brain (Das et al., 2016). Today there is a lot of research being conducted on LSD due to recent laws limiting such research being lifted. Such research includes; LSD Treatment for Alcoholism, LSD Treatment for Opioid and Other Drug Addictions, LSD Studies with Optimism/Openness/ Creativity/Imagination, LSD Treatment for End-of-Life Anxiety/Pain and LSD Treatment for Cluster Headaches. LSD was first created by chemist Albert Hofmann in 1938 as part of his research into the medicinal value of lysergic acid compounds. Recreational use of LSD peaked in the 1960's (Grob, 2002). The manufacture, sale, possession, and use of LSD, known to cause negative reactions in some of those who take it, were made illegal in the United States in 1965 (Grob, 2002). By the early 1970's LSD usage attention was virtually non-existent and would not be revived until the 2000's. Presently, LSD research is thriving.

Summary Videos

Your brain on LSD:

History

The history of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) begins in 1938 in a Sandoz (pharmaceutical research company) research laboratory in Basel, Switzerland (“History of LSD”, n.d.; Schroder, 2014). Albert Hofmann was a 32-year-old recent University of Zurich graduate interested in discovering the properties and applications of the fungus ergot, which grows on rye (Schroder, 2014). Under the leadership of professor Arthur Stoll, Hofmann explains that he isolated alkaloids from ergot, which is the base of lysergic acid, and combined it with amines in peptide linkage (as cited in Ayd and Blackwell, 1971, n.p.). Using this new procedure, various lysergic acid amides were developed (as cited in Ayd and Blackwell, 1971, n.p.). One among them was lysergic acid diethylamide, which was created by combined the ammonia derivative diethylamide with lysergic acid (Schroder, 2014). Hofmann writes that this was, “given the laboratory code name LSD-25 because it was the twenty-fifth compound of the lysergic acid amide series” (as quoted in Ayd and Blackwell, 1971, n.p.).

However, Hofmann’s hopes that LSD-25 could have clinical relevance in manipulating the human circulation and respiration systems were unfounded as the only effect it had on animals when tested was that it caused stimulation (Schroder, 2014). Nevertheless, five years after his initial synthesis, Hofmann felt compelled to resynthesize the compound. While he was nearing the completion of his synthesis, he began to feel unusual and was forced to retire home. Upon his return to the laboratory, Hofmann remarked, “At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination…perceived an uninterrupted steam of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors” (as quoted in Schroder, 2014, n.p.). Thus, this was the first instance of a human experiencing the effects of LSD, albeit accidently, as Hofmann surmised he must have ingested the drug unintentionally while working on it. Having gotten a taste for the effects of LSD, quite literally, Hofmann proceeded to intentionally consume 250 micrograms of LSD and bicycled home with his lab assistant. It was at this pivotal moment that he began to realize the potency of the drug he had created for he began to have fantastic psychological hallucinations accompanied by physical symptoms of confusion (Schroder, 2014). This day is now celebrated as ‘Bicycle Day’ by LSD users (“History of LSD”, n.d.).

After the discovery of LSD and the subsequent popularization of the drug, it became known for its association with various different organizations, people, and cultural movements (“History of LSD”, n.d.). Project MK-Ultra was one such example. It was purported to be a mind-control experimental project created by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the United States of America from 1950 to 1960. The CIA used LSD on unwitting participants in an attempt to test the drug’s efficacy as a psychological weapon of war during the Cold War it was waging against the Soviet Union. There were also several key individuals apart from Hofmann who are associated with the drug. Ken Kesey, the author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, promoted the recreational use of LSD after having used it as a participant of Project MK-Ultra. Kesey, along with several friends, hosted ‘Acid Parties’ in San Francisco where partygoers would ingest LSD and experience its effects in a group setting accompanied with music. Similarly, Harvard psychology professors Timothy Leary and Richard Alpert both experimented with LSD and went on to become promoters of the drug too. Finally, LSD became an important icon of the counterculture that was developing during the 1960s (“History of LSD”, n.d.).

Finally, there is an interesting historical connection between LSD and Canada. Psychiatric research on the effects of LSD on the mind was an aspect of LSD research during the late 1900s (Dyck, 2005). Ewen Cameron of the Allen Memorial Institute conducted research bankrolled by the CIA in Montreal, Quebec. Apart from Cameron, two other Canadian researchers conducted several experiments on the uses of LSD. One was Humphry Osmond of Weyburn, Saskatchewan and the other was Abram Hoffer of Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. They were both interested in investigating the effects LSD had on an individual in creating a psychotic condition used to study schizophrenia. However, due to the increasingly controversial image that LSD had in the public, the government criminalized the drug making their research unsuccessful (Dyck, 2005).

Famous LSD Users

- Bill Gates (Co-founder of Microsoft): In a 1994 Playboy interview he mentioned his experiences with LSD in from mid-20’s. He described them as mind-boggling experiences that helped him understand who he really was (Smith, 2015).

- Steve Jobs (Co-founder of Apple): Stated that his LSD usage in late teens was one of the 2 or 3 most important things he ever did in his life. He credits his outside-the-box perspective to LSD. He claims it helped him think of the world in a different way (Smith, 2015).

- The Beatles (Band): In a 2004 interview Paul McCartney stated that their songs “Day Tripper” and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” are about LSD and that the band wrote several of their songs while on LSD or soon after taking LSD including multiple number one hits (Smith, 2015).

- Francis Crick (Co-discoverer of the structure of the DNA molecule): In a 2004 interview Francis Crick claimed that he and many other researchers at Cambridge would take LSD in small amounts to aid in their thinking. Crick also stated he would be unsure if the discovery of the structure of the DNA would have happened if he did not use LSD (Smith, 2015).

- Katy Mullis (Refined the polymerase chain reaction technique (PCR)): A year after winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1993 for his biochemical breakthrough in refining the PCR he admitted to binging LSD in the 60’s and 70’s. He went to proclaim that LSD was far more important to his accomplishments than any courses he ever took. He went as far as to claim that his entire legacy probably depended LSD (Smith, 2015).

- Doc Ellis (Former MLB Pitcher): Former Major League pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates, once took LCD forgetting he was the planned starting pitcher against the San Diego Padres. He ended up throwing a no-hitter during the game while still under the effects of LCD. He claimed to have not seen any of the batters and was simply trying his best to throw in right direction on the June 12, 1970 night (Smith, 2015).

Others: (Smith, 2015)

- Anthony Bourdain (Chef)

- Phil Jackson (Former NBA Coach/Player)

- Jack Nicholson (Actor)

- Dr. Andrew Weil (American Author and Physician)

Classification

LSD is classified as a psychedelic drug which means its primary function is to alter cognition and perception as well as many other psychological issues (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). LSD is also considered an hallucinogenic, which means it causes hallucinations; this is when people see, hear, smell, taste or feel things that do not exist in reality but do so in their own minds (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). LSD has been known to put individuals in a dream like stage where they see abstract images. LSD is at this point in time strictly a recreational drug and has no purpose outside of producing an altered state of consciousness by modifying the perceptions, feelings, and emotions all for pleasure (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). LSD's classification as recreational drug may not hold true very long with research going on about potentially having LSD used as a treatment for a variety of causes. LSD has well over 40 street names including popular names such as Acid, California Sunshine, Loony Toons, Lucy and Superman (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). Unlike popular recreational drugs such as cocaine and heroin, LSD is a tolerance building drug. In order to produce the same effects, increased quantities of LSD is required after each usage due to the brain obtaining tolerance to the drug (Blachford & Krapp, 2010).

Demographics

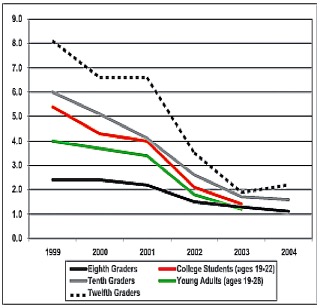

Figure 1 Source: https://www.justice.gov/archive/ndic/pubs11/12620/odd.htm

Figure 1: The percentages of LSD usage in different groups between 1999 and 2004.

The largest demographic group to use LSD are middle/upper-middle class whites (Krebs & Johansen, 2013). Men use LSD more often than women, which is common with all risk taking behaviors including any drug use (Krebs & Johansen, 2013). LSD is rarely taken by individuals above the age of 28. It is implied that the younger population is more willing to have a desire for psychological experiences by going on such psychological trips (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). As seen in figure 1 the usage of LSD has decreased across all age groups as individuals are afraid of the potential brain damage that can occur (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). However, it can be argued that perhaps some of the effects are exaggerated (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). Further, governments limit the distribution of LSD through strict laws (Blachford & Krapp, 2010). Unlike most other recreational drugs, people only take LSD once. In fact, about 89% of LSD users only take it once and never again. This occurs because LSD is not physically addictive (Krebs & Johansen, 2013).

Biochemical Properties

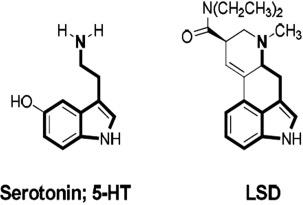

Figure 2 Source: http://www.themindcentre.com.au/microdosing-lsd-psychedelic-drugs-treatment-future/

Figure 2: The structures of Serotonin HT-5 and LSD

LSD is a tasteless, doorless, and colorless crystal in its natural state (Krebs & Johansen, 2013). It is virtually impossible to identify it without actually be told or having not extracted yourself. For recreational use LSD can be taken in a variety of ways, but the most common method is by a dissolving stamp on the tongue (Krebs & Johansen, 2013). It can however also be administered as a liquid and gas through the mouth, nose, eyes, and anus. LSD is water soluble because this compound has the amine groups (Krebs & Johansen, 2013). The water solubility is enhanced by the hydrogen bonding involving the lone pairs of the amine group (Li & Wang, 1998). Also, this compound can decomposes in light and high temperature. It decomposes in the light condition because UV light can induce the C-9,10 double bond of LSD to undergo photocatalytic hydration (Li & Wang, 1998). The LSD molecule is considered unstable and must be stored and cared for appropriately or there is a risk for damage potentially creating an ineffective drug (Li & Wang, 1998). The key biochemical property of LSD is that its structure is very similar to that of serotonin which can be noticed in figure 2. This allows LSD molecules to behave and react in a very similar manner as serotonin in the body such as binding to the same receptors. The additional functional groups on LSD allow the molecule to do the role of serotonin even better than serotonin itself. Such benefits include binding longer to the receptors and avoiding degradation longer (Li & Wang, 1998).

Mechanisms of Action / Pharmacology

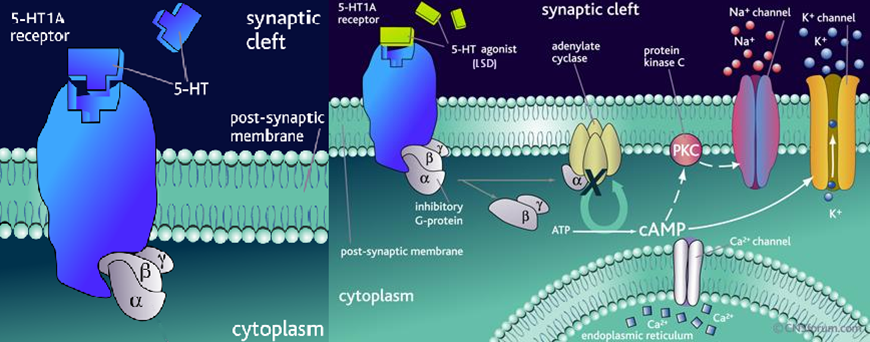

Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) interacts with receptors in the brain known as 5-HT receptors (also known as 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors or serotonin receptors) (Schiff, 2006). Interaction with these receptors results in an agonist (physiological response occurs) or partial antagonist (inhibited physiological responses) on serotonin activity (Schiff, 2006). 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors are the two presynaptic receptors involved in this interaction while 5-HT2 receptors are the postsynaptic receptors (Schiff, 2006). LSD like many other hallucinogens promote the release of glutamate in thalamocortical terminals (Schiff, 2006). Having the release of this neurotransmitter creates a dissociation between sensory relay centers and cortical output (Schiff, 2006). Other than these steps, not much else is known about the mechanism of action for LSD. Figure 3 demonstrates the effectiveness of LSD at mimicking the role of serotonin and the cascade of events that occur post binding that researchers believe occurs (Schiff, 2006).

Figure 3 Source: http://flipper.diff.org/apprulesitems/items/4051

Figure 3: Binding of LSD vs. Serotonin to 5-HT receptors and the potential post cascade.

Effects on the Brain

Brain networks dealing with vision, attention, movement, and hearing become far more connected; this creates what looks like a more connected and unified brain in an individual (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). Other networks in the brain are broken down or disintegrated, leading the activity to become more entropic, meaning that more of a state of disorder is created. This comes about due to these networks becoming separated (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). A scan of a user who took LSD showed that there was a loss of connections between part of the brain called the parahippocampus and another region called the retrosplenial cortex (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). The retrosplenial complex is on the posterior side of the brain and involves spatial navigation of the body. On the other hand, the parahippocampal region of the brain involves memory retrieval and encoding and is the area that surrounds the hippocampus. An individual will experience a feeling of “ego dissolution”, which is a feeling that describes an individual who feels less of being a singular entity and has now become one that is blended with the environment or others around them (Cormier, 2016). In other words, this means that an individual's self-identity is becoming lost. Lastly, lysergic acid diethylamide is not a physically addictive drug, but the drug may become psychologically addicting to the individual. The user may enjoy the trips that they may have and thus become addicted to feeling and experiencing these hallucinations (Das et al., 2016).

Short and Long Term Effects

A dosage of 1–3 µg/kg body weight is enough to produce moderate, behavioral effects (Das, Barnwal, Ramasamy, Sen, & Mondal, 2016). LSD’s effects can be observed within 30-60 minutes of ingesting and can peak over 1-6 hours and dissipates in 8-12 hours (NIDA, 2016). Acute toxicity can upset the gastrointestinal system and cause chills while also stimulating the sympathetic nervous system resulting in hypothermia, palpitation, hypertension, hyperglycemia, tachycardia, and panic (NIDA, 2016; Das et al., 2016). They have dramatic changes in their feelings and sensations such as rapidly changing emotions (NIDA, 2009). LSD can also affect the motor system leading to increased activity of monosynaptic reflexes which result in muscle incoordination, which is considered a symptom of religious ecstasy where the worshipper (user) is displaying the love of God (Aghajanian & Marek, 1999; Das et al., 2016).

Large doses of LSD can cause delusions and visual hallucinations with an altered sense of time and self along with cross-over of senses such as hearing colours and seeing sounds (NIDA, 2009). In some cases, users experience terrifying thoughts and feelings of despair, insanity, death and losing control (NIDA, 2009). Some other mental effects include an impaired perception of depth, time, size, shape of objects, movements, touch, body image as well as an artificial sense of certainty or euphoria(Das et al., 2016; Liester, 2014). They may also experience sudden or delayed flashbacks which may persist, causing distress, impairment in everyday occupational and social functioning (NIDA, 2009). Chronic effects may include flashbacks and worsening latent mental disorders such as schizophrenia and severe depression (Das et al, 2016; NIDA, 2016).

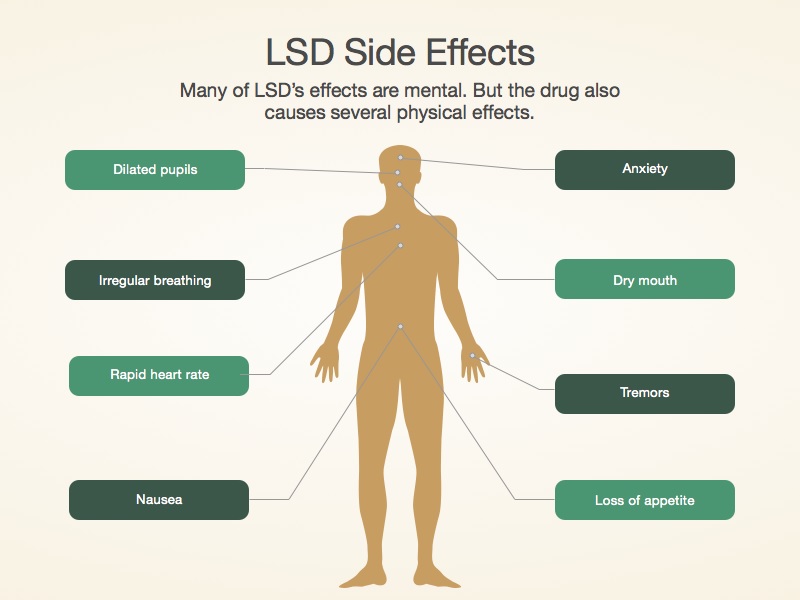

Figure 4 Source: https://www.recovery.org/topics/lsd-facts/

Figure 4: Some of the potential side-effects of LSD usage.

An overdose of LSD leads to “bad trips” which include intense anxiety, combat-behavior, panic, confusion and a simple touch and normal sensations seem strange and bizarre(Das et al, 2016; NIDA, 2016). There are also adverse health effects associated with ingesting LSD and depending on the dosage, it may result in dilation of pupils, high body temperature, increased heart rate and blood pressure as well as lots of sweating, decreased appetite, tremors and dry mouth (NIDA, 2009).

LSD does not cause overpowering drug-seeking behaviour and it is not classified as an addictive drug however, by producing tolerance to LSD, frequent users must intake higher dosage to achieve same intoxication effects (NIDA, 2016). Although there is no withdrawal syndrome or physical dependence on LSD, there is low psychological dependence, but no deaths have been reported entirely due to LSD use (NIDA, 2016).

Usages

LSD is a powerful mood-changing, psychedelic agent, which is mainly used for recreational and spiritual purposes; since it is sold on the illicit market, it is not used in medical treatments although scientists now are speculating its usefulness as a therapeutic agent (Das et al, 2016; NIDA, 2016). It can also be used as a component of psychedelic peak therapy for alcohol and drug dependence in terminally ill patients (Das et al., 2016). Some suggest that these psychedelic drugs have great potential for research in psychiatry and psychology while others suggest the usefulness of its effects in psychotherapy (Das et al., 2016).

Albert Hofmann, the inventor of LSD, stated that this drug allowed access to the spiritual world allowing the user to feel as if their ‘eyes have been cleansed’ and they can ‘see the world as new’ (Das et al, 2016; Grob, 2002; Ruck et al, 1979). LSD also increases the user’s appreciation of the surrounding environment and boosts their creativity, while raising their awareness to mystical and religious experiences (Das et al., 2016; Passie, Halpern, Stichtenoth, Emrich, &Hintzen, 2008).

LSD was once legally available for clinical use in experimental treatments until the late 1960s (Das et al, 2016; Grinspoon L &Bakalar J, 1997). In the early 1960s, LSD along with counseling reduced anxiety, depression and pain in patients with advanced cancer (Das et al., 2016; Kast & Collins, 1964).They reported the use of LSD; in ventilation of emotions in schizophrenics, as therapy for obsessional neurosis and anxiety and psychoanalytic therapy(Das et al., 2016). Clinicians also explored its therapeutic use in anxiety disorders, addictions, obsessive-compulsive disorders and sever depression among other conditions (Das et al., 2016).However, due to the adverse side effects including harmful behaviour, the Hallucinogenic Drug Regulations was implemented in 1967 to limit the use of such drugs only by qualified practitioners(Das et al., 2016).

Finally, some interesting therapeutic uses of LSD suggest that it can act as an antianxiety agent, enhance; user’s creativity, suggestibility and performance (Das et al., 2016). The use of hallucinogenic agents to enhance creativity in artists began in the 1960s and it could alter the sensory modalities of the user, change emotions and expanded their sense of thought, identity and creativity (Das et al., 2016; Dobkin de Rios &Janiger O, 2003). If LSD is ingested as a controlled, therapeutic agent in a proper setting, its mystical experience can allow the patient to develop a deeper level of self-understanding and self-acceptance, but the therapist must have an in-depth knowledge of the patient’s psychopathology (Das et al., 2016).

Social, Economic, and Cultural Implications

LSD Abuse

To understand the social, economic and cultural implications of LSD it is important to first establish the context of LSD abuse. LSD abuse is not similar to other drug abuse. This is because LSD is not physically addictive, but rather is psychologically addictive (Das et al., 2016). Because LSD is such a potent drug whose effects last for such a long time, individuals do not consume LSD each day. However, with prolonged use over many days individuals can develop a tolerance for the drug causing them to have to consume more of the drug to get the same ‘level’ of ‘high’. What is unique about LSD though is that even if tolerance and dependence does build, if the individual were to stop consuming the drug for a period of several days, the dependence would subside. This demonstrates how LSD is not physically addictive (Das et al., 2016).

However, this is not to say there are no side effects of LSD abuse as certainly there are some serious consequences of long-term LSD abuse. One of these consequences is hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder (HPPD) (Hermle et al., 2012). HPPD is defined as a, “long-lasting condition characterized by spontaneous recurrence of visual disturbances reminiscent of acute hallucinogen intoxication” (Hermle et al., 2012). Two examples of HPPD caused by LSD abuse are outlined by Hermle et al. (2012) and Noushad et al. (2015). The former explains the case study of a 33-year-old woman who abused LSD since the age of 18 and now has developed HPPD (Hermle et al., 2012) and the latter explains the case study of a forty-eight-year old man who abused LSD since his twenties and now has HPPD for twenty-five years even after stopping LSD use (Noushad et al., 2015). According to Wu et al. (2008) 16% of hallucinogen users (excluding MDMA i.e. ecstasy users) experience, “at least one clinical feature of hallucinogen use disorder [HUD]” (Wu et al., 2008) and among ecstasy users in the previous year, LSD was also used by 12% of them. This illustrates the danger of LSD as a potential gateway drug to ‘harder’ drugs like ecstasy and developing HUD. In fact, according to the Substance Abuse and Health Services Administration (2015), 246,000 individuals abused hallucinogens in 2014 in America alone and experienced HUD.

Social Implications of Drug Abuse

In light of the evidence, it is obvious that there will be social repercussions of LSD and other hallucinogen abuse. These social implications can be generalized to that of the social impact of drugs. Young adults are particularly affected by drug abuse and they face, “negative effects on health, psychosomatic symptoms, emotional distress, and interpersonal relationships…increased health and family problems” (Newcomb and Bentler, 1988). According to a study done by Saxe et al. (2001), drug abuse also has a socioeconomic slant to it. To be specific, the researchers found out that drug abuse is significantly more evident in low-income communities, but that drug abuse is spread out uniformly over communities of all income brackets. To address these problems, the researchers suggest that, “prevention, treatment, and research” are key priorities to focus on to help combat drug abuse in poorer communities and that an increase in law enforcement is not necessarily the most effective strategy (Saxe et al., 2001).

Economic Implications of Drug Abuse

There are also economic implications to drug abuse. As mentioned earlier because LSD can be a gateway drug to more potent drugs, it is a useful exercise to examine the economic impacts of drug abuse as a whole. This can be done by estimating the economic costs of drug abuse on different parameters, “health, public safety, crime, productivity and governance” (International Narcotics Control Board [INCB], 2013). Regarding health, governments can save $10 for every $1 they invest into treatment and prevention programs for drug abusers. Regarding public safety, drug users are several times more likely to get into accidents while driving. Regarding crime, 55% of criminals report they were under the influence of drugs. Regarding productivity, America loses $120 billion USD as a result of lost productivity from people not working. Lastly, regarding governance, corruption is rampant in governments all over the world due to drug trafficking. All of these factors lead to monetary repercussions (INCB, 2013).

Cultural Implications of LSD

LSD had an enormous impact on culture in the USA. Apart from the examples touched upon earlier in the ‘History’ portion of this wiki page, Rothstein (2008) writes that in the 1960s and in the early 1970s LSD use was very common making LSD usage not so much ‘counter culture’ as it was mainstream. For instance, headshops were common in New York (Rothstein, 2008) before the drug was criminalized. Ramm (2017), in particular, explores a singular example of the cultural impact LSD had on America by considering the Brotherhood of Eternal Love. This was a group organized to combat the government’s attempts to stop the consumption of LSD and were central figures in the Human Be-In event organized in San Francisco 1967. Their ideas stemmed in part from the viewpoints advocated by the author Aldous Huxley- that of the consumption of psychedelics (Ramm, 2017). The Brotherhood of Eternal Love is just one of many examples of the cultural transformation LSD had on America.

Research / Applications

LSD was studied and researched heavily in the 1950’s and 1960’s (Morgan et al., 2017). During this time frame there was the release of more than 1000 academic papers and the publication of several dozen books all on the use of LSD for therapeutic purposes, particularly in the field of psychotherapeutics (Morgan et al., 2017). In the 1960’s, cultural and government backlash lead to the classification of LSD as a schedule I drug which resulted in the abandonment of research in both universities and commercial laboratories (Morgan et al., 2017). Laws limiting research on LSD remained strict until the late 90’s and experimentation/testing in humans was not allowed until 2009 which has since revitalized LSD research (Nichols, 2016). All previous research from the 50’s-60’s is considered invalid due to the lack of scientific process being used, small sample sizes, lack of technology and biases on researchers who either heavily sided with or were against LSD use (Nichols, 2016). Several of the studies done decades ago are now being re-done insuring accurate results in additional to new studies looking at the effects of LCD on the human brain and how it can help with a variety of human troubles varying from physical, to psychological and emotional (Morgan et al., 2017.

LSD Treatment for Alcoholism:

A recent meta-analysis combined the results of 6 randomised controlled trails which assessed the efficacy of LSD as potential treatment for alcoholism (Krebs & Johansen, 2012). The total of 536 participants who were all administrated for alcohol abuse was given either up to 50 micro grams of LCD (significantly less than the normal dosage) or a placebo (control group) on a regular schedule (Krebs & Johansen, 2012). During the testing timeframe all participants would also undergo normal alcohol abuse therapy. All participants would be regularly checked on and would self-report with milestone checks for short-term (3 months), medium-term (6 months) and in the long-term (12 months). At the 3 month mark 59% of active treatment participants showed reliable improvement, meaning they were consuming less alcohol and showed improved results in therapy (Krebs & Johansen, 2012). This was significantly higher than the control groups in which case only 39% demonstrated the same improvement (Krebs & Johansen, 2012). At the 6 month mark this difference drops, but is still very much present. However, by the long-term 12 month check the benefits seen before were not maintained and most participants regained their old habits or plateaued without full recovery (Krebs & Johansen, 2012).

LSD Treatment for Opioid and Other Drug Addictions:

The recent tests were designed similar to the studies done with participants with alcohol addictions were done with those with opioid addictions as well as other drug addictions such as cocaine and heroin (Pisano et al., 2017). The results of such tests were not as positive as those done with alcoholism (Pisano et al., 2017. In the short term the individuals given LSD demonstrated a significant improvement compared to control groups in the same study, but the effectiveness dropped considerably well before the 6 month mid-term point (Pisano et al., 2017).

New Technology and Learning Effects on Brain Mechanisms:

In the last few years studies have started on the acute effects of LSD on brain mechanisms in healthy individuals (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). These individuals have no form of mental illness, no substance abuse issues and are of moderate intelligence (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). Society is more capable of studying such mechanisms due to the betterment of technology and better research skills (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). In the 60’s and 70’s researchers were limited to electroencephalography (EEG), but now have the ability to use emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) which are both considered more effective (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). Many studies are currently using such methods to understand the true effects of LSD on different parts of the brain in order to be able to better find potential suitable uses for LSD (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). One such study used a comprehensive placebo-controlled neuroimaging design to look at which parts of are activated beyond normal levels. 20 healthy patients attended 2 scanning days, 2 weeks apart in a balanced-order, within-subject design for both LSD and placebo (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). Drug/placebo was administrated to all participants. During the sessions both an fMRI and Magnetoencephalography (MEG) were done multiple times before drug activation, while the drug is working as well as well after the effects of the drug have worn off. While the LSD was in effect participants would note down eyes-closed visual hallucinations and the complexity of such visuals (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). When looking at the end results there was significant difference in cerebral blood flow (CBF) with certain portion of the brain (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). Greater CBF was observed under LSD in the visual cortex compared to the placebo group. The magnitude of such increases correlated positively with participants ratings on the complex imagery during their altered state of consciousness (ASC) while under LSD (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016). This would indicate that the visual cortex has a key role in the effects of LSD and that LSD has the capabilities of upregulated its activity. Similar tests have been done on several other brain parts (Carhart-Harris et al., 2016).

Source of Figure 5: http://www.pnas.org/content/113/17/4853.full

Figure 5: An image of the produced results from Carhart-Harris et al. 2016 experiment looking at CBF in the brain and the visual cortex.

LSD Studies with Optimism/Openness/ Creativity/Imagination:

As recent as 2016 studies have occurred looking at the potential impact of LSD on increasing human optimism, openness, creativity, and imagination after the use of LSD (Lebdev et al., 2016). Throughout history many celebrities, inventors and artists have claimed that using LSD helped in their career success. Researchers today want to know if LSD can truly increase brain functions that would led to such success (Lebdev et al., 2016). Testing such factors is often very difficult due to not have a specific scale to measure them with and due to self-report of the participants (Lebdev et al., 2016). However, the testing that has been done have garnered rather positive positives. In one study of note 20 random healthy volunteers received 75 micro-grams of LSD and were asked to come back in 2 weeks later (Lebdev et al., 2016). After, the two weeks had passed all 20 volunteers scored higher on optimism, openness, creativity and imagination tests than they did before taking the LSD. It is also of note that such results hold true even with micro-dosing in which only 1/10 of the usual dosage is required (Lebdev et al., 2016). Although such results cannot be taken as scientific fact it has opened the door to further tests as well as further research on the potential for LSD as an anxiety medication or pain suppressor (Lebdev et al., 2016).

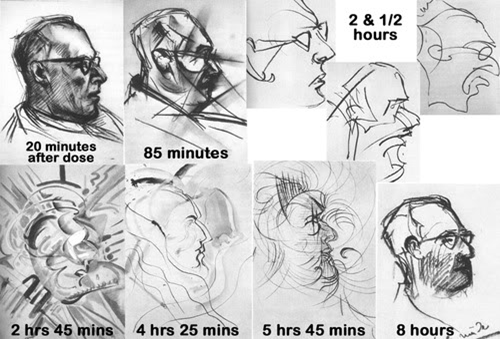

Another interesting experiment looking at the effects of LSD on such traits was done with a single artist (Savage & McCabe, 1973). The artist was given recreational amounts of LSD and was told to draw the researchers ever 10-15 minutes exactly as he saw him. The results of this experiment can be seen in Figure 6 (Savage & McCabe, 1973).

Figure 6 Source: http://www.openculture.com/2013/10/artist-draws-nine-portraits-on-lsd-during-1950s-research-experiment.html

Figure 6: The images drawn by the artist (participant) in the 1973 experiment.

LSD Treatment for End-of-Life Anxiety/Pain:

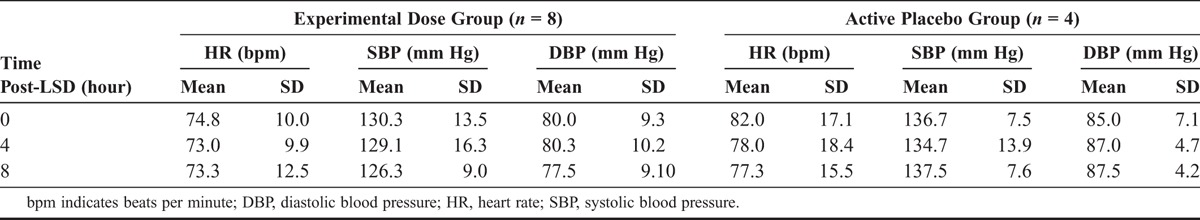

In Switzerland there is ongoing research since 2008 that is looking into using LSD to alleviate anxiety for patients who are terminally ill with cancer in order to cope with their impending deaths (Gasser et al., 2014). The preliminary results of the study are promising and many in the field are excited about the next steps of the treatment. One study found that 12 months after LCD treatment, patients reported a significant reduction in anxiety and a rise in their quality of life with many of the patients stating the treatment helped them change their habits, see the world in a another view as well coming to the realization that death is a part of life (Gasser et al., 2014). Another test looking at the short-term impact of LCD treatments compared the heart rates and blood pressures post LSD treatment between experimental and placebo groups as such variables when abnormally high are strong indicators of anxiety/stress (Gasser et al., 2014). In this group of 12, the 8 experimental participants had significantly lower heart rates and blood pressures than the 4 in the placebo groups immediately after in taking the treatment as well as 4 hours and 8 hours later (Gasser et al., 2014). Through the several studies no negative effects have been reported in the patients. Such results have opened the door for researchers to test LSD with those who are depressed, have phobias, obsessive compulsive disorder, and other anxiety driven psychological issues (Gasser et al., 2014).

Figure 7 Source: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4086777/

Figure 7: HR and BP results results of the Gasser et al., 2014 experiment with terminally ill cancer patients.

LSD Treatment for Cluster Headaches:

Cluster headaches are a neurological disorder characterized by recurring and frequent severe headaches (Passie et al., 2008). These occur on only one side of the head and occur for the most part around the eye (Passie et al., 2008). Only 0.1% of the population experience these in their lifetime (Passie et al., 2008). They are described as feeling worse than natural childbirth or amputation without anesthetics (Passie et al., 2008). There is no treatment for such headaches and using normal pain-killers have caused the pains to increase in severity. Case-reports have indicated that LSD can reduce cluster pain as well as interrupt the cluster-headache cycle preventing future headaches from occurring (Passie et al., 2008). The mechanism of how cluster headaches come about is not well known and thus the effects LSD have on them are also not known but a correlation does seem to exist (Passie et al., 2008). A 2006 study by researchers looked at 53 cluster headache sufferers who were treated with LSD and a majority of the participants reported beneficial effects (Passie et al., 2008). It seems as though for LSD to have a beneficial effect sub-psychedelic dosages are needed. Currently a dose-response study testing the effectiveness of LSD is being conducted (Passie et al., 2008).

Additional Resources

More Information:

MAPS (Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies) was founded in 1986 (MAPS, 2017). MAPS is a non-profit research and educational organization that develops medical, legal, and cultural contexts for people to benefit from the use of psychedelics and marijuana safely, including LSD (MAPS, 2017). The site is a great way to obtain information of LSD, look into current research/projects, donate, ask questions, and is a way to keep up with any relevant developments on the drug. MAPS does not push for the illegal usage of drugs, but rather advocates for safe, legal, and beneficial use of drugs such as LSD (MAPS, 2017).

LSD Addiction and Abuse Help:

For those using LSD and are abusing its use there are plenty of ways to go about getting help (Hermann, 2016). Most local abuse therapy centres or clinics should cover LSD usage issues and help as much as possible (Hermann, 2016). There are also LSD recovery centers for those in more dire situations. Even though LSD is not addictive many people are unable to stop using LSD and/or are no longer satisfied with life outside LSD (Passie et al., 2008). LSD risks can also occur as a vast majority of users if not under control will start taking far more dangerous drugs or will began experimenting (Passie et al., 2008).. There are also a variety of credible websites that can help someone stop LSD usage by following specific instructions (Hermann, 2016). Example: https://www.recovery.org/topics/quitting-lsd/. LSD rehab can include support groups, behavioural therapy, and even family therapy. The important thing to know is that an LSD abuser is never 'alone'. There are always resources to help him or her overcome their psychological addiction.

Conclusion

In conclusion, LSD is a psychedelic drug that alters cognition and perception thus acting as a hallucinogen(Blachford & Krapp, 2010). LSD usage, which peaked in the 1960's, has seen a vast decrease in its usage for all age groups (Krebs & Johansen, 2013). The key biochemical property of LSD is that its structure is very similar to that of serotonin, which allows it to behave and react in a very similar manner as serotonin such as binding to the same receptors (Li & Wang, 1998). Under LSD a wide range of symptoms and effects occur including some parts of the brain being more connected to other parts becoming less connected(Das et al., 2016). Symptoms vary depending the individual and the amount taken (NIDA, 2016). LSD use is limited to recreational use at the moment, but current research has started opening the door for LSD to be used in more important ways. Some examples are: LSD treatment for alcoholism, LSD treatment for opioid and other drug addictions, LSD studies with optimism/openness/creativity/imagination, LSD treatment for end-of-life anxiety or pain, and lastly LSD treatment for cluster headaches. It is important to educate oneself about such drugs, as there are both positive and negative consequences associated with its usage. MAPS is a great organization to look into in order to obtain such new information (MAPS, 2017). It is also important to note there are various help organizations that can assist an individual in overcoming his or her addiction (Hermann, 2016). Ultimately, due to the infancy of LSD research and the incomplete understanding scientists have of all its functions, it is still recommended to avoid taking this illegal drug. By taking such precautionary steps, one can avoid the psychological, physical, emotional, social, and economic consequences, among other things, that can occur if the drug is abused.

References

Aghajanian, G. K., & Marek, G. J. (1999). Serotonin, via 5-HT2A receptors, increases EPSCs in layer V pyramidal cells of prefrontal cortex by an asynchronous mode of glutamate release. Brain Research, 825(1–2), 161–171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-8993

Ayd, F. J., & Blackwell, B. (1970). Discoveries in biological psychiatry.

Blachford, S. L., & Krapp, K. (2010). LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide). Drugs and Controlled Substances: Information for Students. Detroit, MI, USA: Gale.

Blewett D., and Chwelos N. (1959). Handbook for the therapeutic use of lysergic acid diethylamide 25 individual and group procedures. Retrieved from https://www.erowid.org/psychoactives/guides/handbook_lsd25.shtml

Carhart-Harris, R.L., Muthukumaraswamy, S., Roseman, L., Kaelen, M., Droog, W., Murphy, K.,…Nutt, D.J. (2016). Neural correlates of the LSD experience revealed by multimodal neuroimaging. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences, 113(17), 4853-4858. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1518377113

Cormier, Z. (2016). Brain scans reveal how LSD affects consciousness. Nature, 99(2), 4577-4579. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature.2016.19727

Das, S., Barnwal, P., Ramasamy, A., Sen, S., & Mondal, S. (2016). Lysergic acid diethylamide: a drug of ‘use’? Therapeutic Advances in psychopharmacology, 6(3), 214–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/2045125316640440

Dobkin de Rios M., & Janiger O. (2003). LSD, Spirituality and the Creative Process. Rochester, NY, USA: Park Street Press.

Dyck, E. (2005). Flashback: psychiatric experimentation with LSD in historical perspective. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 50(7), 381-388.

Gasser, P., Holstein, D., Michel, Y., Doblin, R., Yazar-Klosinski, B., Passie, T., . . . Brenneisen, R. (2014). Safety and efficacy of lysergic acid diethylamide-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with life-threatening diseases. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 202(7), 513–520. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000113

Grinspoon L., & Bakalar J. (1997). Psychedelic Drugs Reconsidered. New York, NY, USA: Lindesmith Center.

Grob C. (2002). Conversation with Albert Hofmann. In Grob C (Ed.), Hallucinogens: A Reader (pp. 15–22). New York, NY, USA: Tarcher/Putnam.

HISTORY.com. (n.d.). History of LSD. [online] Available at: http://www.history.com/topics/history-of-lsd [Accessed 4 Nov. 2017].

Hermann, E. (2016). What You Should Know About Quitting LSD. Retrieved from https://www.recovery.org/topics/quitting-lsd/

Hermle, L., Simon, M., Ruchsow, M., & Geppert, M. (2012). Hallucinogen-persisting perception disorder. Therapeutic Advances in Psychopharmacology, 2(5), 199–205. http://doi.org/10.1177/2045125312451270

International Narcotics Control Board (2013). Economic Consequences of Drug Abuse. International Narcotics Control Board, pp.1-4.

Kast, E. C., & Collins, V. J. (1964). Study of lysergic acid diethylamide as an alangestic agent. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 43, 285–291. Retrieved from https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=14169837

Krebs, T. S. & Johansen, P. O. (2012). Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) for alcoholism: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 26(7), 994-1002. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881112439253 Krebs, T. S., & Johansen, P.O. (2013). Over 30 million psychedelic users in the United States. F1000Research, 2, 98. http://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.2-98.v1

Liester, M. B. (2014). A review of lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) in the treatment of addictions: historical perspectives and future prospects. Current Drug Abuse Reviews, 7(3), 146–156. https://doi.org/10.2174/1874473708666150107120522

Lebedev, A.V., Kaelen, M., Lövdén, M., Nilsson, J., Feilding, A., Nutt, D.J., . . . Carhart-Harris R.L. (2016) LSD-induced entropic brain activity predicts subsequent personality change. Human Brain Mapping, 37(9), 3203–3213. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23234

Lewis, R.J. (2007). Hawley's Condensed Chemical Dictionary 15th Edition (pp. 773). New York, NY., John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Li, Y. Z., McNally, A. J., Wang, H. Y., & Salamone, S. J. (1998). Stability study of LSD under various storage conditions, Journal of Analytical Toxicology, 22(6): 520–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/jat/22.6.520

MAPS (2017). What Is MAPS?. Retrieved from http://www.maps.org/

Morgan C., McAndrew, A., Stevens, T., Nutt, D., & Lawn, W. (2017). Tripping up on addiction: the use of psychedelic drugs in the treatment of problematic drug and alcohol use. Current Opinion in Behavioral Science, 13, 71-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2016.10.009

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2016). Hallucinogens. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/hallucinogens%20on%202017

National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA). (2009). Hallucinogens: LSD, Peyote, Psilocybin, and PCP. Retrieved from https://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/hallucinogens09.pdf

Newcomb, M. D., & Bentler, P. M. (1988). Impact of adolescent drug use and social support on problems of young adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of abnormal psychology, 97(1), 64.

Nichols, D.E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological Reviews, 68(2), 264-355. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

Noushad, F., Al Hillawi, Q., Siram, V., & Arif, M. (2015). 25 years of Hallucinogen Persisting Perception Disorder-A diagnostic challenge. British Journal of Medical Practitioners, 8(1), 37-40.

Passie, T., Halpern, J. H., Stichtenoth, D. O., Emrich, H. M., & Hintzen, A. (2008). The pharmacology of lysergic acid diethylamide: a review. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 14(4), 295–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00059.x

Pisano, V.D., Putnam, N.P., Kramer, H.M., Franciotti, K.J., Hapern, J.H., & Holden, S.C. (2017). The association of psychedelic use and opioid use disorders among illicit users in the United States. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 31(5), 606-613. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117691453

PubChem. (2017). Lysergide. Retrieved from https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5761

Ramm, B. (2017). The LSD cult that transformed America. [online] Bbc.com. Available at: http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20170112-the-lsd-cult-that-terrified-america [Accessed 4 Nov. 2017].

Rothstein, E. (2008). How LSD Altered Minds and a Culture Along With It. [online] Nytimes.com. Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/05/arts/05conn.html [Accessed 4 Nov. 2017].

Ruck, C. A., Bigwood, J., Staples, D., Ott, J., & Wasson, R. G. (1979). Entheogens. Journal of Psychedelic Drugs, 11(1–2), 145–146. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/522165

Samhsa.gov. (2015). Substance Use Disorders | SAMHSA - Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [online] Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/disorders/substance-use [Accessed 4 Nov. 2017].

Savage, C., & McCabe, O.L. (1973). Residential psychedelic (LSD) therapy for the narcotic addict: a controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 28, 808-814. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1973.01750360040005

Saxe, L., Kadushin, C., Beveridge, A., Livert, D., Tighe, E., Rindskopf, D., … Brodsky, A. (2001). The Visibility of Illicit Drugs: Implications for Community-Based Drug Control Strategies. American Journal of Public Health, 91(12), 1987–1994.

Schiff, P. L. (2006). Ergot and its alkaloids. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 70(5), 98. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1637017/

Shroder, T. (2014). The Accidental, Psychedelic Discovery of LSD. [online] The Atlantic. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2014/09/the-accidental-discovery-of-lsd/379564/ [Accessed 4 Nov. 2017].

Smith, P. (2015). 7 People Who Say They Owe Their Huge Success to Psychedelics. Retrieved from https://www.alternet.org/drugs/seven-high-achievers-credit-psychedelics-their-success

Wu, L.-T., Ringwalt, C. L., Mannelli, P., & Patkar, A. A. (2008). Hallucinogen Use Disorders Among Adult Users of MDMA and Other Hallucinogens. The American Journal on Addictions / American Academy of Psychiatrists in Alcoholism and Addictions, 17(5), 354–363. http://doi.org/10.1080/10550490802269064