Table of Contents

Bipolar Disorder

Introduction

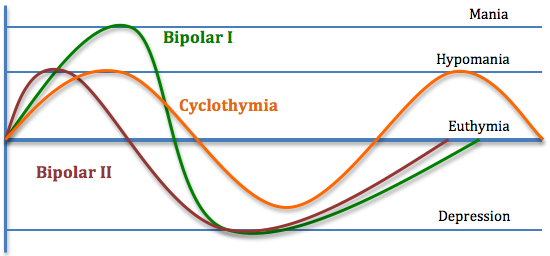

Bipolar disorder (BD) is also known as manic depression and is a mental illness that expresses extreme high and low moods. The onset of BD can also cause changes in sleep, energy, thinking and behaviour. Individuals who do suffer from BD experience periods where they feel very happy and energized and other periods where they feel very sad, hopeless, and down. There are times between these two phases where they feel normal. The highs and lows are like “poles” of mood, hence, “bipolar” disorder. The term “manic” are the times in which an individual would feel those “highs” of over excitement and confidence. Many times, these emotions can lead someone to making impulsive and reckless decisions. Sometimes, during the manic period, individuals can experience delusions, for example believing in things that aren’t true and it becomes hard to talk them out of these ideas, and hallucinations, like seeing or hearing things that aren’t there. Hypomania is a term used to describe mild symptoms of mania. During this time, an individual may not experience the delusions or hallucinations and their extreme high symptoms don’t stop them from completing everyday activities. Depressive phases are times when an individual feels very sad or depressed. Most people spend more time in the depressive phase rather than the hypomanic or manic phases (Bipolar Disorder, 2005).

Bipolar Disorder Type I & II

There are also two major classifications of BD which are known as Bipolar I disorder and Bipolar II disorder. BD I involve phases of extreme mood episodes ranging from mania to depression. BD II is a milder form of mood swings which consists milder episodes of hypomania and phases of extreme depression (Bipolar Disorder, 2005).

Cyclothymic Disorder

Cyclothymic disorder is classified as brief periods of hypomanic symptoms that can be described as short periods of depressive symptoms that aren’t as long-lasting that are expressed in hypomanic or depressive episodes (Bipolar Disorder, 2005).

Mixed Features

Mixed features is a term used when referring to simultaneous symptoms of opposite mood polarities during manic, hypomanic or depressive episodes. This can be identified as high energy, sleeplessness, and racing thoughts. However, at the exact same time, the individual the person may feel hopeless, despairing irritable, and suicidal (Bipolar Disorder, 2005).

Rapid-Cycling

Rapid-cycling is used to describe having four or more mood episodes within a 12-month time period. Episodes need to last for a certain number of days to be considered a distinct episode. Some individuals experience changes in polarity within a single week or even a day. In this case, this may be called ultra- rapid cycling, which can be argued in psychiatry that this isn’t a valid or well-established phenomenon in bipolar disorder. Rapid-cycling can happen at any time in the course of the disease, however, it is more prevalent later on in life and in the duration of the disease. This classification can increase the risk of severe depression and suicide attempts (Bipolar Disorder, 2005).

Figure 1: This image is used to outline and explain the major classifications for bipolar disorder.

Diagnosis

The most important diagnostic method is to speak to a physician about the severity, length and frequency of changes in mood, lifestyle or behaviors. The physician bases the diagnosis on the severity of the symptoms as outlined by the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or DSM-V. While making the diagnosis, the health practitioner will often ask questions about family history of bipolar disorder or other mental health illnesses since there is a genetic component to bipolar disorder (Bipolar Diagnosis, n.d.).

When speaking specifically about BD I and BD II there are specific criteria for the manic, hypomanic and depressed phases that need to be met in order to be diagnosed with one of the two mental illnesses. Criteria consist of the following:

Bipolar I: Manic

A. “A distinct period of abnormally and extreme mood and abnormally increase in activity or energy, lasting at least 1 week and present most of the day, nearly every day.

B. During the period of mood disturbance and increased energy or activity, three (or more) of the following symptoms:

· Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity.

· Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep).

· More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking.

· Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing.

· Distractibility (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli), as reported or observed.

· Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually) or psychomotor agitation (i.e., purposeless non-goal-directed activity).

· Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments).

C. The mood disturbance is severe enough to cause damage on social or occupational functioning

D. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition (DSM fifth edition, n.a).”

Bipolar I: Hypomanic

A. “A distinct period of abnormally and extreme mood and abnormally increase in activity or energy, lasting at least 1 week and present most of the day, nearly every day.

B. During the period of mood disturbance and increased energy or activity, three (or more) of the following symptoms:

Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity.

Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep).

More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking.

Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing.

Distractibility (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli), as reported or observed.

Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually) or psychomotor agitation.

Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments).

C. The episode is associated with a change in functioning that is uncharacteristic of the individual when not symptomatic.

D. The disturbance in mood and the change in functioning are observable by others.

E. The episode is not severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning or to necessitate hospitalization. If there are psychotic features, the episode is, by definition, manic.

F. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication, other treatment) or another medical condition (DSM fifth edition, n.a).”

Bipolar I: Depression

A. “Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure.

Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report (e.g., feels sad, empty, or hopeless) or observation made by others (e.g., appears tearful).

Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day (as indicated by either subjective account or observation).

Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month), or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day.

Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day.

Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others; not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down). Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day.

Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick).

Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others).

Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, or a suicide attempt or a specific plan for committing suicide.

B. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

C. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition (DSM fifth edition, n.a).”

Bipolar II: Hypomanic

A. “A distinct period of abnormally and persistently elevated, expansive, or irritable mood and abnormally and persistently increased activity or energy, lasting at least 4 consecutive days and present most of the day, nearly every day.

B. During the period of mood disturbance and increased energy and activity, three (or more) of the following symptoms have persisted (four if the mood is only irritable), represent a noticeable change from usual behavior, and have been present to a significant degree:

1. Inflated self-esteem or grandiosity.

2. Decreased need for sleep (e.g., feels rested after only 3 hours of sleep).

3. More talkative than usual or pressure to keep talking.

4. Flight of ideas or subjective experience that thoughts are racing.

5. Distractibility (i.e., attention too easily drawn to unimportant or irrelevant external stimuli), as reported or observed.

6. Increase in goal-directed activity (either socially, at work or school, or sexually) or psychomotor agitation.

7. Excessive involvement in activities that have a high potential for painful consequences (e.g., engaging in unrestrained buying sprees, sexual indiscretions, or foolish business investments).

C. The episode is associated with an unequivocal change in functioning that is uncharacteristic of the individual when not symptomatic.

D. The episode is not severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning or to necessitate hospitalization. If there are psychotic features, the episode is, by definition, manic.

E. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a drug of abuse, a medication, other treatment) or another medical condition (DSM fifth edition, n.a).”

Bipolar II: Depression

A. “Five (or more) of the following symptoms have been present during the same 2-week period and represent a change from previous functioning; at least one of the symptoms is either (1) depressed mood or (2) loss of interest or pleasure.

1. Depressed mood most of the day, nearly every day, as indicated by either subjective report (e.g., feels sad, empty, or hopeless) or observation made by others (e.g., appears tearful).

2. Markedly diminished interest or pleasure in all, or almost all, activities most of the day, nearly every day (as indicated by either subjective account or observation).

3. Significant weight loss when not dieting or weight gain (e.g., a change of more than 5% of body weight in a month), or decrease or increase in appetite nearly every day. 4. Insomnia or hypersomnia nearly every day.

5. Psychomotor agitation or retardation nearly every day (observable by others; not merely subjective feelings of restlessness or being slowed down).

6. Fatigue or loss of energy nearly every day.

7. Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt (which may be delusional) nearly every day (not merely self-reproach or guilt about being sick).

8. Diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others).

9. Recurrent thoughts of death (not just fear of dying), recurrent suicidal ideation without a specific plan, a suicide attempt, or a specific plan for committing suicide.

B. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

C. The episode is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance or another medical condition (DSM fifth edition, n.a).”

Epidemiology

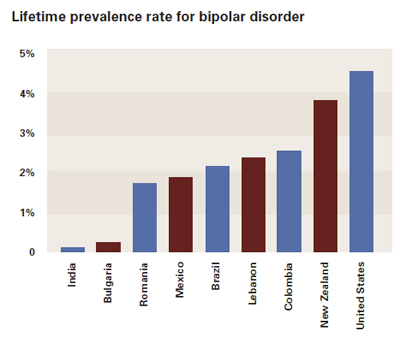

Kathleen Merikangas of the National Institution of Mental Health conducted a well known survey. Her team distributed their surveys to adults in eleven different countries located all around the world. The countries included: The United States, Mexico, Brazil, Columbia, Bulgaria, Romania, China, India, Japan, Lebanon, and New Zealand. Results showed that the United States had the highest lifetime rate if BPD at 4.4%. India has the lowest with 0.1%, Japan showed to have a prevalence of 0.7% and Columbia, which was a low- income nation had a high prevalence of 2.6% (NewsMedical, 2011).

The results were also able to identify that less than half of the BPD patients received mental health treatment at some point in time. In low -income countries, 25.2% of individuals had contact with a mental health system. Approximately 50% of those individuals mentioned that they started experiencing their symptoms in adolescence, however, they never thought about treatment as an option (NewsMedical, 2011).

Experts explain that the high prevalence of BPD in the United states could be genetic or environmental. It may also be because different cultures deal and respond to mental illnesses differently. “Cultural awareness plays a big role in psychiatry. Some cultures have a huge reluctance to speak about psychiatric things.” Some cultures may not acknowledge mental illness as well as others. In the United States, individuals may be more prone to being diagnosed because they are more aware of the condition. Many low-income countries may have higher levels of stigma, resulting in fewer people speaking up about their symptoms (NewsMedical, 2011).

Figure 2: This image outlines the main results from the study done by Merikangas et al.

Societal Impact

Family Impact

. Emotional distress such as guilt, grief, and worry

o Family members think they are the cause of the onset of BP in an individual

· Disruption in regular routines o Because of an individuals extreme emotional phases, changes to daily activities may have to change to ensure to not cause more pressure or stress

· Having to deal with bizarre or reckless behaviour

· Financial stresses as a result of reduced income or spending sprees

o Individuals may be reckless with their spending

o May have extra costs for treatment and therapy

· Strained marital or family relationships

· Changes in family roles

· Difficulty in maintaining relationships outside the family

· Health problems as a result of stress (Mood Disorders Association, n.a)

Physiological Effects

.During periods of mania or hypomania, psychological consequences to these phases include:

.Auditory and visual hallucinations

.Delusions, including delusions of grandeur and thoughts that objects are sending special messages

.Intense anxiety, agitation, aggression, paranoia

.Obsessive worried thoughts and feelings; feeling the need to check something

.Feeling like life is spinning out of control

.Heightened mood, exaggerated optimism and self-confidence

.Racing thoughts; rapidly changing streams of thought; easily distractible (Tracy, 2016)

During periods of depression, psychological effects of this phase include:

.Prolonged sadness

.Feeling helpless, hopeless and worthless; feelings of guilt

.Pessimism, indifference; reoccurring thoughts of death and suicide

.Inability to concentrate, indecisiveness

.Inability to take pleasure in former interests (Tracy, 2016)

.Physical effects of BP include the decrease of productivity during times of severe depression. BP can lead to an increase in productivity in times of the manic phase, however, these irregular behaviour leads to job loss.

The physical effects of BP include:

.Increased physical and mental activity and energy; hyperactivity

.Significant changes in appetite and sleep patterns

.Trouble breathing

.Racing speech

.Social withdrawal

.Loss of energy, persistent lethargy; aches and pains

.Unexplained crying spells

.Poor overall health

.Weight gain; blood pressure and heart problems; diabetes (Tracy, 2016)

Causes/Risk Factors

The root cause of bipolar disorder is unknown, however, various risk factors can trigger the onset of the illness (Mayo Clinic Staff Print, 2017). One cause of bipolar disorder is due to biological differences (Mayo Clinic Staff Print, 2017). Those who are often affected by bipolar disorder have physical changes in their brains (Mayo Clinic Staff Print, 2017).

The second cause is due to genetics, where individuals who have a first-degree relative affected by bipolar disorder are more susceptible to also suffer from bipolar disorder (Mayo Clinic Staff Print, 2017). Children who have one parent affected by the disorder have a 10-25% chance of developing of the disorder, while children with both parents affected by the disorder have a 10-50% chance of developing the disorder (Bipolar Disorder, n.d.). In the case of identical twins, there is a range of 40-70% chance of the other twin developing the disorder. The range is large due to the fact that genes are not the only contributing factor to the disorder, environment, and one’s lifestyle habits also contribute to the development of the disease (Bipolar Disorder, n.d.).

In addition, one’s environment can trigger the onset of bipolar disorder. For example, stressful or traumatic events such as a death or loss of a loved one can trigger the onset of bipolar disorder. Research shows that about 50% of individuals suffering from bipolar disorder have a substance use problem (Bipolar Disorder, n.d.). Life style habits such as drug or alcohol abuse and lack of sleep may trigger bipolar disorder.

Symptoms

Symptoms of bipolar disorder include high moods (mania) and low moods (depression). Bipolar 1 disorder is characterized by at least one manic episode, while hypomania is characterized by at least one episode of hypomania and a major depressive disorder. Hypomanic episodes are similar to manic episodes except that they do not entail psychosis, hospitalization or severe functional impairment.

Mania and hypomania include three or more of the following symptoms: “abnormal upbeat, jumpy, or wired; increased activity, energy or agitation; exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria); decreased need for sleep; unusual talkativeness; racing thoughts; distractibility; poor decision-making (Mayo Clinic Staff Print, 2017).”

A major depressive episode includes five or more of these symptoms: “depressed mood; marked loss of interest; significant weight changes; insomnia or sleeping too much; restlessness; fatigue; feelings of worthlessness or excessive guilt; decreased ability to concentrate; indecisiveness; planning or attempting suicide (Mayo Clinic Staff Print, 2017).

General symptoms of bipolar disorder include anxious distress, melancholy, psychosis, sleep dysregulation, increased prevalence of suicidal thoughts among others. However, bipolar disorder is often difficult to identify in children and teens (Mayo Clinic Staff Print, 2017). The most obvious symptom of bipolar disorder evident in children and teenagers may be severe mood swings, which are different from the usual (Mayo Clinic Staff Print, 2017). Some co-occurring conditions include: Anxiety disorders, eating disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), alcohol or drug problems and physical health problems (Mayo Clinic Staff Print, 2017).

Pathophysiology

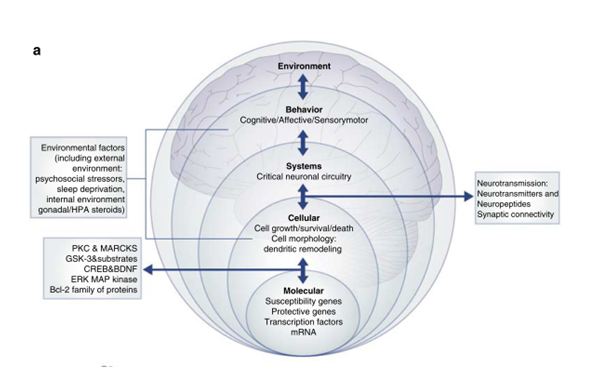

Abnormalities in the synaptic and cellular plasticity

A growing body of data suggests that BD arises from abnormalities in the synaptic and neuronal plasticity cascades, which leads to aberrant information processing in critical synapses and circuits. BD can be conceptualized as being a genetically influenced disorder of synapses and circuits, rather than simply having deficits or excesses in individual neurotransmitters (Schloesser, Huang, Klein, & Manji, 2008).

Over the past 40 years, neurobiological studies of mood disorders have primarily focused on abnormalities of the monoaminergic neurotransmitter systems, on characterizing alterations of individual neurotransmitters in disease states, and on assessing response to mood stabilizer and antidepressant medications. The monoaminergic system consists of a network of limbic, striatal and prefrontal cortical neuronal circuits thought to support the behavioral and visceral manifestations of mood disorders (Drevets, 2000). It is hypothesized that BD arises from the complex interaction of multiple susceptibility and protective genes and environmental factors. The phenotypic expression of the disease includes mood disturbance, as well as cognitive, motor, autonomic, endocrine and sleep or wake abnormalities (Schloesser et al., 2008).

Figure 3 shows the pathophysiology of BD from different perspectives, and how these different systems are interlinked. For instance, there are different physiological levels at which the disease manifests: molecular, cellular, and behavioral. In addition, there are environmental factors which also contribute to the onset of BD (Schloesser et al., 2008). Once there is a dysfunction in one physiological level, it has been observed in the literature that there is a cascade of downstream events which are ultimately responsible for primary abnormalities in signaling pathways.

Figure 3: Different physiological levels contributing to the pathophysiology of BD. Retrieved from Schloesser et al., 2008.

Many signaling pathways play critical roles not only in synaptic plasticity, the cellular process that results in lasting changes in the efficacy of neurotransmission, but also in the long-term atrophic processes. Therefore, plasticity plays a role in the cascading effect for the pathophysiology of the disease (Schloesser et al., 2008).

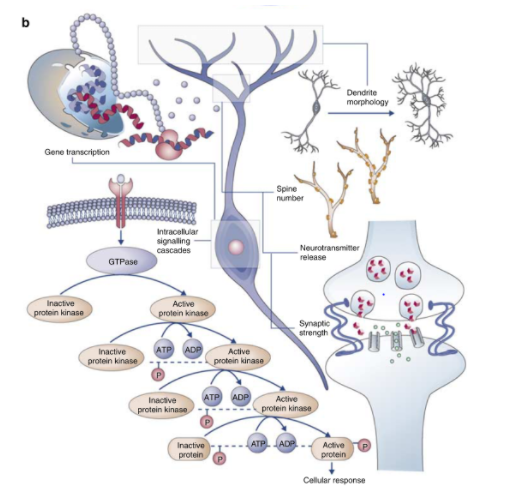

In healthy humans, there are numerous biological mechanisms which underlie neuroplasticity, a broader term that encapsulates changes in intracellular signaling cascades and gene regulation, modifications of synaptic number and strength, variations in neurotransmitter release, modeling of axonal and dendritic architecture, and in some areas of the CNS, the generation of new neurons. The remarkable plasticity of neuronal circuits is achieved through different biological means, including alterations in gene transcription and intracellular signaling cascades. These changes thereby modify diverse neuronal properties such as neurotransmitter release, synaptic function and even morphological characteristics of neurons. However, it has been shown that people with BD have abnormalities in cellular signaling cascades that regulate diverse physiologic functions, thereby causing tremendous medical comorbidity associated with BD (Figure 4) (Schloesser et al., 2008).

Figure 4: Cellular signaling cascades that regulate diverse physiologic functions have shown to be disrupted in patients with BD. Retrieved from Schloesser et al., 2008.

Structural Neuroimaging Findings

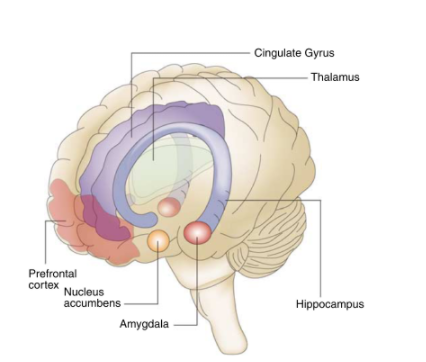

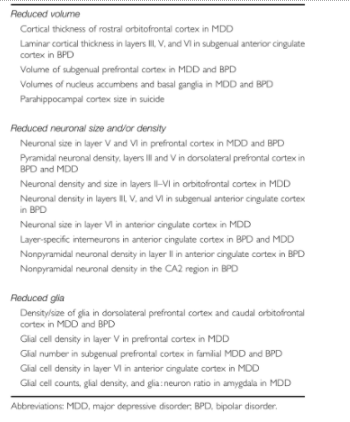

Many forms of neural plasticity involve structural changes in the brain. Since neuroplasticity and cellular cascade changes play a role in BD, many studies to date have used neuroimaging and postmortem human brains to investigate the potential alterations in structural plasticity in mood disorders. Studies on people with BD using the aforementioned pathological techniques have revealed several functional and structural abnormalities in brain regions involved in the perception and control of mood states and emotions. These include the prefrontal cortex (PFC), amygdala, insula, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex, and ventral striatum (Figure 5). In addition, post-mortem morphometric brain studies in mood disorders have demonstrated that patients with mood disorders undergo cellular atrophy and/or loss (Table 1) (Schloesser et al., 2008).

Figure 5: Neuroanatomical regions which are implicated in the perception and control of mood states and emotions are affected in patients with BD. Retrieved from Schloesser et al., 2008.

Table 1: Studies using post-mortem brains with mood disorders show cellular atrophy and/or loss. Retrieved from Schloesser et al., 2008.

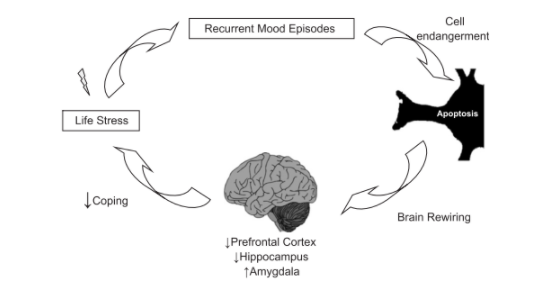

Allostatic load in Bipolar Disorder

Allostatic load (AL) is the bodily “wear and tear” that emerges due to the effects of chronic stress in general health. In patients with BD, AL offers an insight into why patients who undergo recurrent mood episodes are clinically perceived less resilient, and thereby, more susceptible to comorbid diseases. AL helps explain the stress- and episode-induced changes in the brain regions involved in the emotional circuitry, which then lead to dysfunctional processing of information. This in turn makes BD patients more vulnerable to environmental stressors, episodes and drug abuse (Kapczinski et al., 2008).

HPA axis and circadian rhythm disturbances

The hypothalamic-pituitary axis (HPA) axis, is altered in mood disorders. Abnormalities in cortisol levels have been found in patients suffering from mood disorders. These changes in cortisol levels are central to the concept of AL (Kapczinski et al., 2008). A study by Cervantes et al. in 2001, showed that bipolar patients in different phases of the disease- depression, mania/ hypomania and remission, had higher levels of cortisol than healthy controls (Cervantes et al., 2001). It is postulated that the elevated cortisol levels may have important long-term consequences, such as neuroplastic alterations in the hippocampus, amygdala and prefrontal cortex. Elevated cortisol levels altering HPA axis also change several aspects of circadian rhythms, including sleep regulation, which then cause AL in BD. Further, many studies in the literature have shown the effects of sleep deprivation on the body, including impairment of brain function, increase inflammatory response, increase cortisol, insulin and blood glucose levels (Kapczinski et al., 2008).

Amygdala and emotional processing

Chronic stress is known to induce hyperactivation of the amygdala, enhancing amygdala-dependent unlearned fear, fear conditioning and aggression. Patients with BD appear to have abnormalities in the emotional processing involving the amygdala circuitry. Functional neuroimaging studies have shown increased activity of the amygdala during acute mood episodes. Amygdala-related circuits seem to be overactive, but dysfunctional in patients with BD. Such malfunctioning is postulated to render BD patients more vulnerable to stress and thereby, leading to increased AL (Kapczinski et al., 2008).

Prefrontal cortex and coping

The prefrontal cortex (PFC) is a key brain region involved in the regulation of emotional behaviour, executive function and fear extinction. This area is sensitive to the remodeling effects of stress. Several studies have shown structural and functional frontal lobe abnormalities (reduction in size) in BD, including the anterior cingulate and subnegual PFC. These are consistent with the cognitive deficits found in BD (Kapczinski et al., 2008).

Figure 6 encapsulates the brain rewiring that happens after recurrent stress and mood episodes in BD patients. Neural substrate reactivity is altered in BD patients, leading to cell endangerment, pro-apoptotic cascades, thereby leading to altered size of brain parts involved in emotional processing and coping. Such brain rewiring is related to increased emotionality and poor coping which render subjects more vulnerable to life stress (Kapczinski et al., 2008).

Figure 6: The image summarizes the cycle of brain rewiring in patients with BD. Retrieved from Kapczinski et al., 2008.

Treatments

Types of Care

Primary and Secondary Care

When assessing the care that individuals with BD seek, the following statistical analyses provide key insight:

- ¾ of individuals with BD do not receive the optimal care

- ¼ of individuals with BD do not seek for primary/secondary care for issues pertaining to mood

Primary care attenders attend a large portion of individuals with BD, therefore this form of support allows for an effective form of detection and diagnosis. The diagnosis and treatment plan for patients can take up to 8 years for individuals to receive secondary care services. There is a great amount of misdiagnosis of BD due to the numerous consultants and care providers involved in the process of diagnosis. Primary caregivers are responsible for managing the physical and mental health care of individuals with BD, while ensuring that their own health is intact. BD can cause caregivers to develop depression and anxiety, therefore primary care must constantly be assessed and monitored (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2006).

Figure 7: Visual representation of diagnosis between a primary care attender, such a physician, and a BD patient. Retrieved from https://s.sharecare.com/img/video/stills/2538422639001_bipolar_treated.jpg

Self-management

It is imperative for individuals with BD to develop a systematic approach at managing their symptoms over a long-term. The ability to make informed decisions regarding their treatments allows individuals with BD to develop a stronger grasp and increased confidence in their ability to be independent. The extent to which these individuals take responsibility must be carefully monitored through coping mechanisms, as they may not understand the diagnosis completely, thus resulting in risky behaviour or abandoning the use of medications. Individuals with BD are able to monitor their moods by documenting it in a diary and assessing the triggers that onset manic or depressive episodes. An organization called ‘The BiPolar Organization’ provides individuals with BD and their caregivers self-management training programs in the UK. It is important to note that the optimal form of care comes from the collaborative approach of diagnosis, treatment and management through consultations between the patient, caregiver and medical professional (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2006).

Psychological Therapy

The primary goal of psychological therapy is to prevent and minimize relapses in mood swings for individuals with BD. Therapeutic techniques assess mood changes, coping mechanisms, enhance the effects of pharmacotherapy and ensure better communication within family members (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2006). Psychotherapy can be categorized into short-term and long-term treatments. Short-term therapies are led by the therapist and focus on current issues that the patient faces. Long-term therapy lasts for a year or longer, and the therapist minimizes their involvement in carrying out conversation. Instead, the patient seeks to understand underlying issues that they may have experienced in the past and/or presently. Current combination therapies consisting of psychological and medical treatments are most effective in preventing relapses for individuals who are out of acute episodes or for stable patients (Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, n.d.).

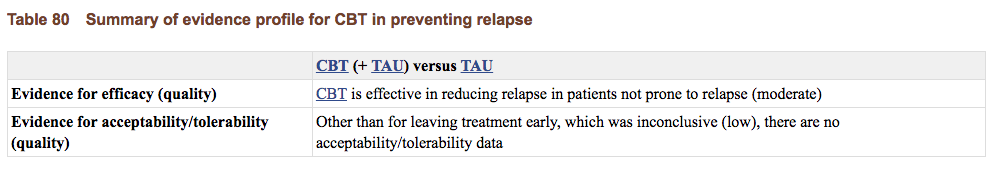

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy

This common form short-term psychotherapy is applicable to managing and treating numerous mental illnesses. Individuals with BD work with the therapist in identifying their thoughts, feelings, symptoms and areas of conflict. This part of CBT allows the individual to be cognizant of their mood transitions, thus allowing them to develop the necessary skills to assess, monitor and combat the manic and depressive states. The therapist and the patient are able to develop goals and design a management routine that is effective and pertains to the individual’s concerns and symptoms. In a RCT of 457 individuals between the ages of 39-52 diagnosed with Bipolar Disorder I or II were assessed for the effectiveness of CBT. An overall summary of evidence for CBT preventing relapse shows that CBT is effective in comparison to no psychological therapy. Furthermore, the addition of CBT to standard care practises was more effective than the care on its own, because individuals in the CBT group had significantly fewer acute bipolar episodes in comparison to the control group over 12 months and 30 months (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2006).

Figure 8: Results from RCT of CBT of individuals with BD show that CBT is effective in preventing relapses. Retrieved from National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2006.

Group/Family Therapy

For individuals with BD, the environment in which they surround themselves in is crucial for managing their symptoms. In group and family therapy, issues that may have existed prior to the diagnosis of BD may be uncovered, thus allowing individuals to communicate and provide a strong support network. It is important for family members to be aware of and educated of the ways in which they should approach an acute episode. Peer support groups allow individuals with BD to share their experiences with one another, and ensure that they are not alone in this process towards coping positively. Members develop strong attachments to one another, as they are able to understand themselves through understanding each other (Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, n.d.).

Psychoeducation

Psychoeducation is a form of CBT that delivers modes of intervention to patients and their families for managing BD. It is important that psychoeducation is catered to the needs of each individual. Information can be given to the patients in a one-on-one basis or group basis, or to the families and caregivers. Psychoeducation can be presented in various forms, such as written work, audio, and video, to accommodate the patient’s needs (Smith, Jones, & Simpson, 2010).

Numerous RCTs that have been conducted within the last 10 years publish data that supports the theory that psychoeducation is effective for individuals with BD. In a study done by Colom et al. (2003), group psychoeducation sessions took place over the course of 21 sessions. Information pertaining to the illness, adhering to treatment, early detection of symptoms and recurrences of symptoms were discussed with the individuals. A control group with participants who took the same pharmacotherapy and psychiatric care were not presented with specific psychoeducational material. In comparison to the control group, individuals gaining educational support has fewer relapsed patients, a decreased number of recurring symptoms and increased time in the transition periods from depressive to manic to hypomanic stages (Colom et al., 2003).

Pharmacotherapy

Once a diagnosis has been made, the first line of treatment involves the use of pharmacological agents. Usually, effective treatments combine medication and psychotherapy due to the long term nature of this disease. Therefore, medications allow individuals to have symptomatic recovery. The goal is to essentially prevent relapse and enhance social and occupational functioning. Treatment of both phases of the illness can be extremely difficult because the same treatments that alleviate depression can exacerbate mania, hypomania or rapid cycling (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

Unfortunately due to our scarce knowledge of the disease mechanism and of pharmacological targets, there are few treatments that are truly effective for bipolar disorder. Most medications are based on an extension of use from other psychiatric disorders (Mayo Clinic, 2017). However, lithium is unique because its main therapeutic use is in bipolar disorder and its mechanism of action is an important place for the identification of future targets.

Additionally, it is important to understand that different types of medication help control different symptoms. That is why it is not uncommon for individuals to try various medicines to find the ones that work for them at the right dosages. Evidently, this can be very frustrating for patients.

Generally, there are three classifications of medications:

Mood Stabilizers

These are medicines that treat and prevent highs (manic or hypomanic episodes) and lows (depressive episodes). They also help to minimize the negative effects of mood fluctuations on functioning. Not all drugs have equal ‘anti-manic’ and antidepressant effects and their primary use is to treat full episodes of mania or depression, episodes that each can last for several days or weeks.

- Lithium

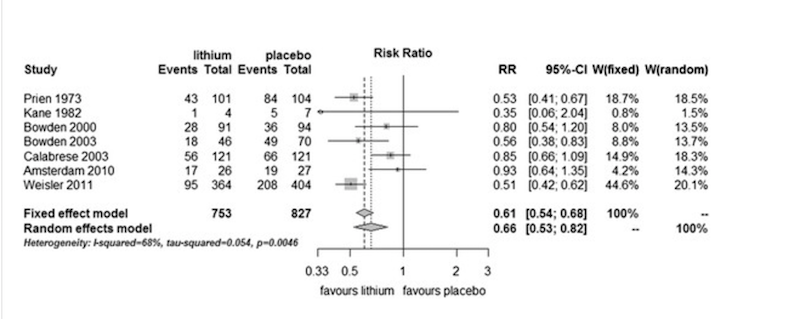

This is one the the oldest and least expensive mood-stabilizing drugs on the market. This drug is more effective at treating mania than depression. According to the literature, it is effective in reducing symptoms and frequency of episodes with a response rate of up to 70% to 80% for the initial manic phase of bipolar. However, it also requires regular blood test and monitoring for kidney and thyroid function. According to the APA, first line therapy is lithium with an anticonvulsant such as valproate (Mayo Clinic, 2017). To solidify the evidence supporting lithium use, a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing lithium with placebo as a long-term treatment in bipolar disorders was conducted. The study showed that lithium was more effective than placebo in preventing overall mood episodes , manic episodes, and dependent on the type of analyses applied, depressive episodes [Figure 9](Severus et al., 2014).

Figure 9: Prevention of any episodes in bipolar patients in RCTs comparing lithium with placebo. All trials show that placebo is inferior to lithium. Retrieved from: http://journalbipolardisorders.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s40345-014-0015-8

- Lamotrigine

This is classified as an anticonvulsant (or antiepileptic) and is more useful for depressive symptoms than manic. There are a variety of anticonvulsants on the market, as one does not work for everyone. Some common ones are: Carbamazepine (Tegratol), Lamotrigine (Lamictal) and Valproic acid (Depakote). Some of these medications also work for other psychiatric symptoms like anxiety, or binge eating (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

A meta-analysis of individual patient-level data from five trials of lamotrigine in bipolar depression reported a modest treatment effect, but one of the trials reviewed showed statistically significant benefits of treatment with lamotrigine in comparison with placebo. Therefore, the place of lamotrigine in acute treatment remains uncertain (Geddes, & Miklowitz, 2017).

Atypical Antipsychotics

These medications are used alone or in combination with other mood stabilizers in patients with bipolar mania. They can reduce or eliminate symptoms of psychosis, like delusions and hallucinations. They used to be referred to as major tranquilizers. They are the main class used to treat schizophrenia (“CAMH: Antipsychotic Medication”, 2017).

- Antipsychotic medications

These are used as a short-term treatment for bipolar disorder to control psychotic symptoms such as hallucinations, delusions, or mania symptoms. Commonly used medications include: haloperidol (haldol), loxapine (Loxitane) or risperidone (Risperdal). Newer drugs that have been added to this category are: aripiprazole (Abilify), asenapine (Saphris), cariprazine (Vraylar), olanzapine (Zyprexa) quetiapine fumarate (Seroquel), and ziprasidone (Geodon) (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

- Benxodiazepines

These are to help patients with acute mania and relieve insomnia.These drugs belong to a group of medications called central nervous system (CNS) depressants, which act on neurotransmitters to slow down normal brain function. CNS depressants are commonly used to treat anxiety and sleep disorders and are sometimes prescribed as adjunctive therapy with bipolar disorder.Benzodiazepines affect the neurotransmitter gamma-aminobutryic acid (GABA). By increasing GABA in the brain, these drugs have a sedative effect (“Benzodiazepines”, 2017).

Commonly used benzodiazepines include alprazolam (Xanax), clonazepam (Klonopin), diazepam (Valium), and lorazepam (Ativan). These drugs all carry the risk of being addictive (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

Antidepressants

These are controversial due to the fact that their effectiveness has not been proven yet are commonly prescribed to patients.

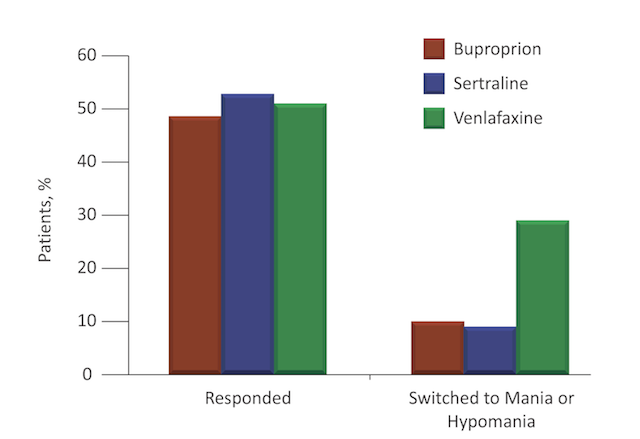

Earlier clinical trials suggested that when SSRIs (Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors) were given with antimony treatments, the SSRIs were more effective and more likely to induce mania than placebo. A study by Post et al. found that different antidepressants appear to have different propensities for triggering an affective switch, possibly because of their differing mechanisms of action. They found that the antidepressant venlafaxine, conferred the greatest risk (Post et al., 2006) [Figure 10]. Essentially, no antidepressant is proven to be effective in bipolar depression but it seems to work for some patients but not others (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

Figure 10: Response and Manic/Hypomanic switch rates for different antidepressants. Retrieved from: http://www.cmeinstitute.com/psychlopedia/Pages/bipolardisorder/9iddt/sec3/section.aspx

Antidepressants used in the treatment of bipolar depression include bupropion (Wellbutrin), fluoxetine (Prozac), and sertraline (Zoloft). Side effects for these medications include: nausea, tremors, sexual dysfunction, weight gain and liver failure. Regular monitoring of these individuals is recommended but the side effects subside in a few weeks (Mayo Clinic, 2017).

References

1. Benzodiazepines. (2017). Healthline. Retrieved 23 March 2017, from http://www.healthline.com/health/bipolar-disorder/benzodiazepines

2. Bipolar Disorder. (2015, November). Retrieved March 25, 2017, from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/bipolar-disorder/index.shtml

3. Bipolar Disorder. (2005, September). Retrieved March 25, 2017, from http://www.webmd.com/bipolar-disorder/mental-health-bipolar-disorder#1

4. Bipolar Disorder: Effects on the family. (n.d.). Retrieved March 26, 2017, from http://www.heretohelp.bc.ca/factsheet/bipolar-disorder-effects-on-the-family

5. Bipolar and Related Disorders. (n.a). Retrieved March 25, 2017, from http://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm03

6.Bipolar Disorder: Who's at Risk? (n.d.). Retrieved March 22, 2017, from http://www.webmd.com/bipolar-disorder/guide/bipolar-disorder-whos-at-risk#2

7. CAMH: Antipsychotic Medication. (2017). Camh.ca. Retrieved 24 March 2017, from http://www.camh.ca/en/hospital/health_information/a_z_mental_health_and_addiction_information/antipsychotic_medication/Pages/antipsychotic_medication.aspx

8. Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (n.d.). Treatments for bipolar disorder. Retrieved March 29, 2017, from http://www.camh.ca/en/education/about/camh_publications/info_guides/bipolar-info-guide/Pages/Treatments-for-bipolar-disorder.aspx#psych

9. Colom, F., Vieta. E., Martinez-Aran, A., Reinares, M., Goikolea, JM., Benabarre, A., Torrent, C., Comes, M., Corbella, B., Parramon, G., & Corominas, J. (2003). A randomized trial on the efficacy of group psychoeducation in the prophylaxis of recurrences in bipolar patients whose disease is in remission. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, (4), 402-4027. http://10.1001/archpsyc.60.4.402

10. Geddes, J., & Miklowitz, D. (2017). Treatment of bipolar disorder. The Lancet. Retrieved 23 March 2017, from http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(13)60857-0/abstract

11. Kapczinski, F., Vieta, E., Andreazza, A. C., Frey, B. N., Gomes, F. A., Tramontina, J., … & Post, R. M. (2008). Allostatic load in bipolar disorder: implications for pathophysiology and treatment. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 32(4), 675-692.

12. Mayo Clinic. (2017). Bipolar Disorder. [online] Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bipolar-disorder/diagnosis-treatment/treatment/txc-20308001 [Accessed 25 Mar. 2017].

13. Mayo Clinic Staff Print. (2017, February 15). Symptoms and causes. Retrieved March 21, 2017, from http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bipolar-disorder/symptoms-causes/dxc-20307970

14. National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). (2006). Bipolar disorder: The management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and adolescents, in primary and secondary care. Leicester, UK: British Psychological Society.

15. Post, R., Altshuler, L., Leverich, G., Frye, M., Nolen, W., & Kupka, R. et al. (2006). Mood switch in bipolar depression: comparison of adjunctive venlafaxine, bupropion and sertraline. The British Journal Of Psychiatry, 189(2), 124-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.013045

16. Prevalence of bipolar disorder. (2011, March 07). Retrieved March 25, 2017, from http://www.news-medical.net/news/20110307/Prevalence-of-bipolar-disorder.aspx

17. Schloesser, R. J., Huang, J., Klein, P. S., & Manji, H. K. (2008). Cellular plasticity cascades in the pathophysiology and treatment of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(1), 110-133.

18. Severus, E., Taylor, M., Sauer, C., Pfennig, A., Ritter, P., Bauer, M., & Geddes, J. (2014). Lithium for prevention of mood episodes in bipolar disorders: systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal Of Bipolar Disorders, 2(1). http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s40345-014-0015-8

19. Smith, D., Jones, I., & Simpson, S. (2010). Psychoeducation for bipolar disorder. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 16 (2), 147-154. http://10.1192/apt.bp.108.006403

20. Tracy, N. (2016, June). Effects of Bipolar Disorder - Bipolar Information - Bipolar Disorder. Retrieved March 26, 2017, from http://www.healthyplace.com/bipolar-disorder/bipolar-information/effects-of-bipolar-disorder/

21.Written by Jaime HerndonMedically Reviewed by. (n.d.). Risk Factors for Bipolar Disorder. Retrieved March 21, 2017, from http://www.healthline.com/health/bipolar-disorder/bipolar-risk-factors#Possibleriskfactors3