Table of Contents

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Introduction

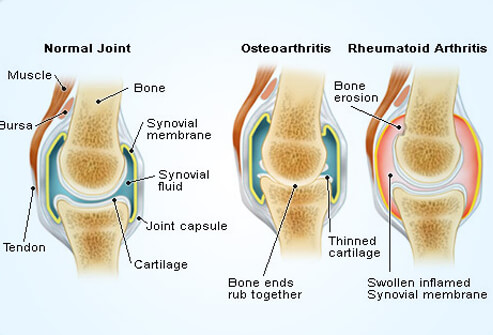

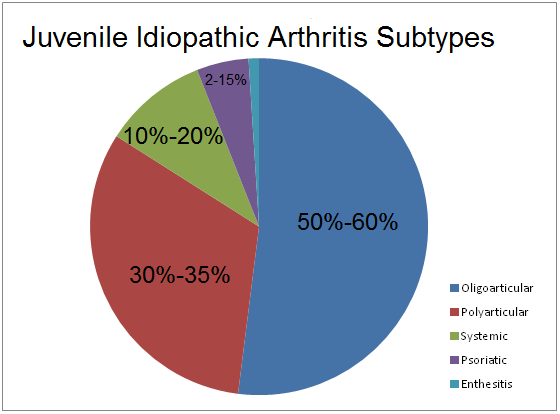

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), also known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is a chronic form of arthritis that can be seen in children between the ages of 1-16 (Shiel, n.a). This disease refers to a group of conditions that pertain to joint inflammation (Figure 1). According to The Genetics Home Reference, “It is classified as an autoimmune disorder which means that the immune system malfunctions and attacks the body’s organs and tissues, in this case joints.” Through much research, it has been determined that there are seven types of JIA which are classified in accordance to their signs and symptoms, number of affected joints, results from medical tests and familial history. All seven types of JIA are chronic, thus individuals must develop coping methods that are long lasting and effective. The prevalence of the seven types of JIA are shown in Figure 2 (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Figure 1: This image illustrates a comparison between a normal joint, osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Retrieved from: http://www.onhealth.com/content/1/rheumatoid_arthritis_ra

Systemic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis causes inflammation in one or more joints, and its symptoms include high daily fevers that can last up to two weeks either preceding or accompanying the arthritis. A skin rash or enlargement of lymph nodes, liver or spleen are symptoms that differentiate this type of juvenile arthritis from other types (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Oligoarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis refers primarily to the inflammation of joints. This form of arthritis is prevalent in four or fewer joints in the first six months from when the disease was diagnosed. Depending on the onset of the condition, this form of arthritis can be divided into two subtypes. If the arthritis has not spread to more than four joints after six months, it is considered to be persistent oligoarthritis. If more than four joints are affected, it is classified as extended oligoarthritis (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Rheumatoid Factor Positive Polyarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

When inflammation is present in five or more joints within the first six months of the disease, it is considered rheumatoid factor positive polyarticular JIA. Patients with this condition have a positive blood test for proteins called rheumatoid factors. A rheumatoid factor is the amount of protein found in the blood that may attack healthy tissues in the human body. This type of JIA displays symptoms similar to the predominant types of arthritis in adults (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Rheumatoid Factor Negative Polyarticular Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

This type of arthritis is similar to the rheumatoid factor positive polyarticular JIA as it also affects five or more joints. As evident in its name, it tests negative for the rheumatoid factor in the blood (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Psoriatic Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis is usually detected in combination with a skin disorder called ‘psoriasis’. This condition is understood by the red patches and irritated skin that are covered by flaky, white scales. Depending on the individual, some are affected by this skin disease prior to developing arthritis, and others notice the the skin condition while first developing arthritis. Other symptoms of this type of arthritis include abnormalities of the fingers and nails like uneven lengths and deformed fingers or vision problems (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Enthesitis-related Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis is classified by tenderness where the bone meets the tendon, ligament, or other connective tissue. This is usually accompanied by inflammation in joints and other related areas (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Undifferentiated Arthritis

Undifferentiated arthritis is given to patients who have symptoms that are not explained by the descriptions of any of the above forms of JIA or who have fit the criteria for more than one of the given descriptions of JIA (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Figure 2: This graph shows the percentage at which each subtype of JIA is prevalent. Retrieved from: https://warmsocks.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/jiabreakdown.png

Symptoms and Diagnosis

JIA is diagnosed once symptoms are persistent for at least six weeks since the diagnosis (Shiel, n.a). Common symptoms of JIA include swelling, redness, and warmth of joints. Researchers and scientists have attempted to formulate a criteria for the precise diagnosis of JIA (Nelson & Kilegman, 2016). The proposed criteria includes six requirements. Firstly, polyarticular or monoarticular arthritis must be present for at least six weeks or in the presence of Iritis, rash, flexion contractures, ankyloses, muscle wasting, anemia, white blood cell count of 20000, and/or cervical spine pain. The criteria of symptoms for polyarticular or monoarticular arthritis present for 6 weeks or less includes no migraines for at least 1 week, no symptomatic response to therapeutic blood levels of salicylate (20 mg/100 ml or above), preponderance of small joint involvement, involvement of the temporomandibular joints, and/or morning stiffness. Next, polyarticular or monoarticular arthritis present for 6 weeks or less is accompanied by pericarditis in the absence of endocarditis. Fourthly, the criteria includes constitutional symptoms, which are known as any combination of fever, weakness, or weight loss . The fifth criteria mentions the presence of elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Lastly the exclusion of all other diagnoses such as rheumatic fever, systemic lupus erythematosus, periarteritis nodosa, dermatomyositis, scleroderma, tuberculosis synovitis, leukemia, lymphoma, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, sickle cell anemia and serum sickness. This criterion was put together to ensure that the diagnosis of JIA was accurate (Grossman & Mukhopadhyay, 1975).

Flares

Flares are known as a classification of symptoms referring to joint pain and inflammation, which are more prevalent in areas of the body highlighted in figure 3. Flares can last from time periods ranging from weeks to months. JIA patients tend to have periods of remission where these symptoms aren’t as prevalent as they would have been in the past. Following this grace period where pain is minimal, these symptoms can reappear, and this is known as a relapse. This notion of relapsing and remission varies from patient to patient and can also be a known trend with other symptoms as well (Shiel, n.a).

Figure 3: This shows the location of different body parts with high prevalence of body inflammation Retrieved from: http://www.onhealth.com/content/1/rheumatoid_arthritis_ra

Fever

A fever is a common symptom for JIA and can be classified according to various degrees of a spectrum. A fever in an individual who may have JIA can be recognized in three different states. “Intermittent fever with a daily single high spike of temperature to 104-105 fahrenheit , then returning down to a normal temperature. A remittent fever with a persistent elevation of 100-101 fahrenheit with occasional, somewhat irregular increases in temperature to 103-104 fahrenheit. Lastly, low grade fever with periodic elevation of temperature to 100-101 fahrenheit, the elevations frequently occurring in the late afternoon or evening, the morning temperature being normal (Grossman & Mukhopadhyay, 1975).”

Morning Stiffness

Morning stiffness is a symptom that helps with the diagnosis of JIA. It is describes as the difficulty in moving muscles after a period of rest or inactivity. Individuals feel this pain in the morning after waking up, and it is not a result of pain. With increased activity and movement throughout the day, muscles become less stiff. Muscle stiffness can last between several minutes to several hours. The degree to which morning stiffness occurs can also vary. It can be severe to the extent that the child cannot move without help from another person. In these circumstances, the combination of a warm bath and an increase in activity will aid with the relief of the stiffness. Other times in the day where morning stiffness is prevalent is after a nap or sitting down for a prolonged period, however, this is usually not as sever as the morning occurrence. Morning stiffness is an important differential characteristic between the symptoms of JIA/rheumatic fever and septic arthritis (Miller, 1994).

Rheumatoid Rash

This symptom is extremely helpful when diagnosing JIA, especially in the acute onset of disease. According to Miller, “the characteristic rheumatoid rash is an erythematous, salmon-pink, evanescent, usually circumscribed macular (although occasionally maculopapular) eruption involving the trunk, neck, velar aspect to the arms, inner aspect of the thighs, buttocks and face. It may last for only a few minutes, a few hours or several years.” Again, the degree to which the rash may last varies between a few minutes to many hours. It appears strongly during times of high fever or during warm baths. Many times, the rash experienced in patients who have JIA can be mistaken for erythema annulare or marginatum, however erythema annulare or marginatum do not spread to facial regions (Miller, 1994).

Figure 4: This image is showing the rheumatoid rash when present on a child’s face. Retrieved from: http://www.findarthritistreatment.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Skin-rash.jpg

Subcutaneous Nodules

Nodules have been observed in approximately 10% of children who have been diagnosed with JIA and can appear subcutaneously, as shown in figure 5. Characteristics of nodules include variances in sizes (from a few millimeters to several centimetres in diameter), nontender texture, no attachment to overlying skin and therefore moving freely under the skin . Many times, they are found over the extensor tendon sheath of the hands, specifically over the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints . They are also found near the olecranon process of the elbow, over the anterior tibial surfaces and around the wrists and when fever is prevalent in the patient, nodules are found along the tendons of the erector spinae group and over the aponeurosis of the scalp (Miller, 1994).

Figure 5: This image illustrates what nodules look like on the hands of a child. Retrieved from: http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/ddb/rheumatoid_nodules_1_low.jpg

Uveitis Eye condition

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis can also lead to an eye condition called uveitis, also named iridocyclitis or iritis . This may or may not lead to any symptoms arising, however some symptoms of this condition are red eyes, eye pain, vision changes and sensitivity to light. Uveitis is known as the swelling and irritation of the uvea, which is the middle layer of the eye (Goldstein et al, 2013).

Blood Tests for JIA

Rheumatoid factor (RF) is a protein that is produced in the blood in some forms of arthritis. This is more common in adults with rheumatoid arthritis, however it is found in 5% of children with JIA (SickKids, 2012). The RF test is a test that is used to detect and measure levels of a specific antibody directed against the blood component immunoglobulin (Arthritis Foundation, 2016).

The liver function test (LFT) is a test that determines whether or not the liver is healthy and working normally. There are many medications that are used to treat arthritis, such as methotrexate. Medications may play a role in overburdening the liver, therefore doctors may order an LFT to determine the medication that is causing the damage (Arthritis Foundation, 2016).

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) is a test used to look at autoantibodies in the blood. Autoantibodies are proteins in the immune system, and they are effective indicators used to determine whether children and teenagers with JIA have an increased risk for eye disease (SickKids, 2012).

Complete Blood Count (CBC) measures three types of cells that are found in the blood: red cells, white blood cells and platelets. This test is useful when discovering more about the condition. For example, kids with low red blood cell counts are usually the ones who are suffering from JIA (Arthritis Foundation, 2016).

Causes and Risk Factors

It has been determined that most cases of JIA are sporadic, meaning that they occur in patients who don’t necessarily have a history of the disorder in their family (Genetics Home Reference, 2015). With that being said, there are many predisposed factors that affect the prevalence of JIA. Infectious agents, immunologic abnormalities of the host, physical trauma to joints, psychological trauma to the child, and allergic reactions to drugs, foods, or toxins can all potentially lead the diagnosis of JIA. With that being said, there is ultimately no clear evidence that proves that these are leadings causes of JIA. JIA is not considered to be a familial disease except in the place in which there is an onset of pauciarticular arthritis. Furthermore, there has been no evidence showing that JIA is transmissible. Various kinds of JIA have been shown to differ in sex, age, types of complications and prognosis, however epidemiologic studies have not been able to clarify these observations (Schaller, 1997). A small percentage of cases of JIA have shown to have run in the family, however the inheritance pattern of the conditions remains unclear (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Maternal smoking has also been observed in the onset of JIA. A mother who smokes while pregnant can induce some permanent immunological abnormality in the child which can later lead to development of arthritis in the child. Smoking while pregnant may also result in a low birth weight which could in turn lead to an increase in the susceptibility to infection and JIA. Lastly, second-hand smoking leads to a contaminated environment in which the risk of JIA during the early years of that child’s life increases (Symmons, 2005).

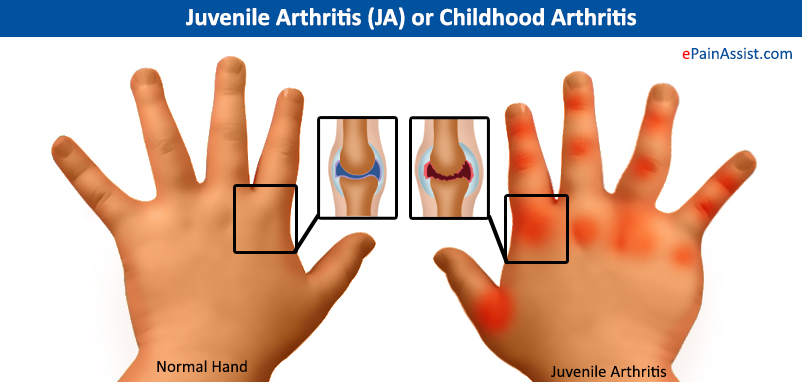

Figure 6: This image illustrates where rheumatoid arthritis is present on a hand. Retrieved from: https://www.epainassist.com/images/Juvenile-Arthritis.jpg

Epidemiology

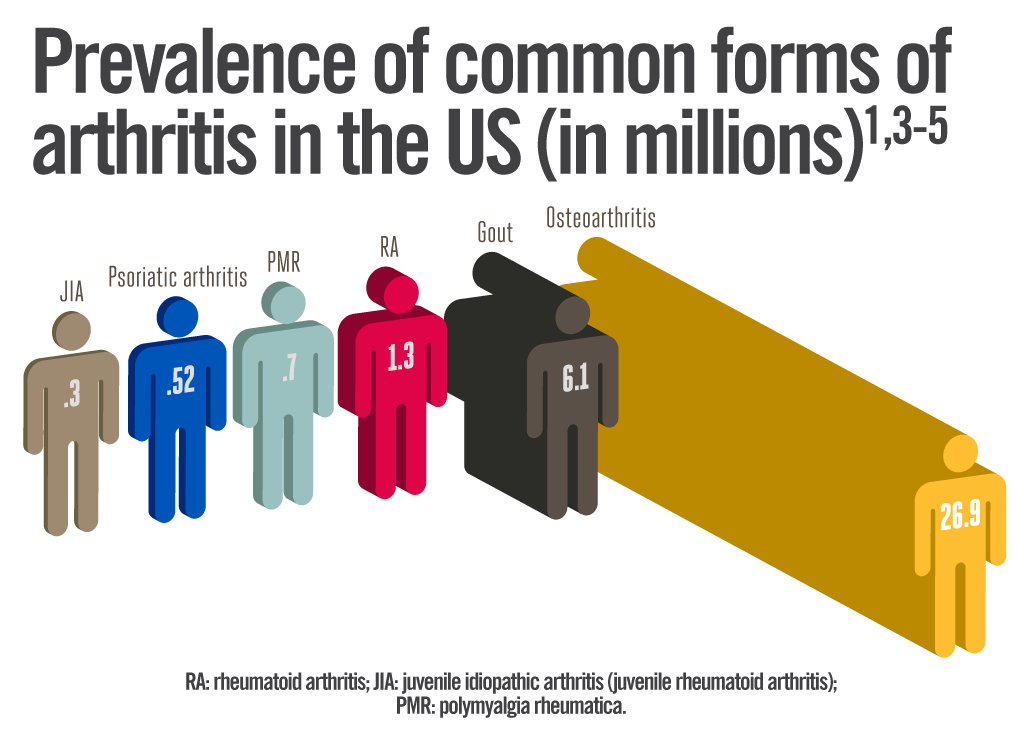

The incidence of JIA in North America and Europe is 4 - 16 affected children out of a sub-population of 10000 children. 1 in 1000, or approximately 294000 children in the United States, are affected by the most common type of JIA in the United States, which is oligoarticular JIA. For reasons that continue to be studied, females seem to be affected with JIA more frequently than males. In the case of enthesitis-related JIA, males are affected more often than females. Furthermore, the incidence of JIA varies between different populations and ethnic groups (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Figure 7: This image shows the prevalence of the common forms of arthritis in the United States. Retrieved from: https://rheumatoidarthritis.net/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/prevalence_arthritis.png

In a study conducted by Saurenmann et al, questionnaires pertaining to ethnicity were distributed to patients with JIA in the Toronto region and then followed up at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. Upon the analysis of the results, the frequency of JIA in European descendants had about 69.7% of their patients diagnosed with JIA, which patients in the Toronto region has about 54.7%. Statistically, lower incidences of JIA were shown in individuals from black, Asian, or Indian subcontinental origins. Kids from the European origin had a higher relative rate for developing any of the subtypes of juvenile arthritis other than oligoarthritis or psoriatic. Patients of the Asian origin showed to have a greater chance of being diagnosed with enthesitis-related JIA while those of black or Native North American origin were more likely to develop polyarticular rheumatoid positive JIA (Saurenmann, 2007).

Pathophysiology

Genetic Susceptibility

JIA is believed to be a complex genetic trait. A complex genetic trait is defined as phenotypes not exhibiting classic mendelian inheritance patterns and therefore, cannot be attributed to variants in a single gene locus. Thus, JIA is a disease which is believed to be determined by a number of genetic and environmental factors (Glass and Giannini, 1999).

HLA and non-HLA Polymorphisms

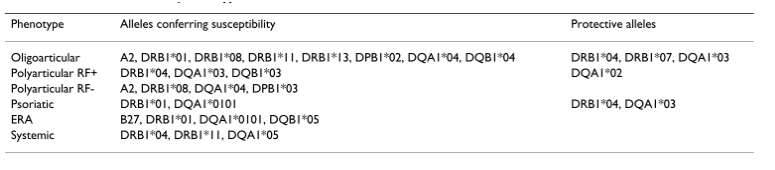

There are two broad categories for genetic susceptibility genes: human leucocyte antigen (HLA) genes and non HLA-related genes. As a polygenic disease, JIA is mostly affected at the HLA region, while the non-HLA loci exhibit moderate or weak genetic influence on susceptibility (Prahalad and Glass, 2008). JIA is influenced by both HLA class I and HLA class II alleles, which contain certain peptides leading to the activation of certain autoreactive T cells (Wedderburn et al., 2001). Several genetic studies have shown the contribution of polymorphisms in the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). The MHC region is on chromosome 6 and is packed with more than 200 genes, many of which are essential to the immune system. Since MHC class II genes play a great role as a genetic risk factor for JIA, CD4+ T cells play a crucial role in disease development. Associations between HLA polymorphisms and JIA subtypes have been reported in multiple populations (Figure 8) (Prahalad and Glass, 2008).

Figure 8:This figure shows several associations between JIA subtypes and different HLA alleles. Retrieved from (Prahalad and Glass, 2008).

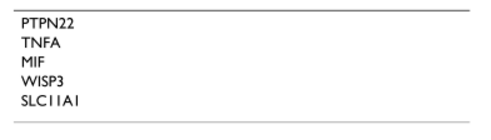

In addition to associations between numerous HLA variants and JIA, non-HLA polymorphisms have also shown to be linked to JIA. For example, genes such as PTPN22, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha (TNFA), MIF, WISP3 and SLC11A6 have been associated with JIA (Figure 9) (Prahalad, 2004; Rosen et al., 2003).

Figure 9:This figure shows non-HLA genetic genes associated with JIA that have been independently confirmed. Retrieved from (Prahalad and Glass, 2008)

Twin Studies

Family studies have provided strong evidence for genetic factors contributing to the susceptibility to JIA. For instance, twin and affected sibling pair (ASP) studies have supported the role for genetic susceptibility to JIA. Specifically, they have shown that monozygotic twin concordance rates for JIA vary between 25 to 40%, a stark contrast to the population prevalence of 1 in 1000 of having the disease (Ansell et al., 1969; Baum and Fink, 1968; Savolainen et al., 2000).

In the largest twin study from the JIA ASP registry conducted by Prahalad and colleagues in 2000, 14 pairs of twins concordant for JIA registered in the National Institute for Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases were analyzed. Of these 14 pairs of monozygotic twins, 12 were concordant for presence or absence of anti-nuclear antibodies. Prahalad and colleagues found that the first twins to develop JIA did so with an average of 5.5 months before the second twins. This was statistically significant and different compared to the 104 non-twin affected siblings pairs in the registry, who showed a 37 month difference in age at onset between the first and second sibling (Prahalad et al., 2000). Together, these studies solidify evidence for genetic factors in the susceptibility to JIA.

Genetic Variables Underlying Autoimmunity

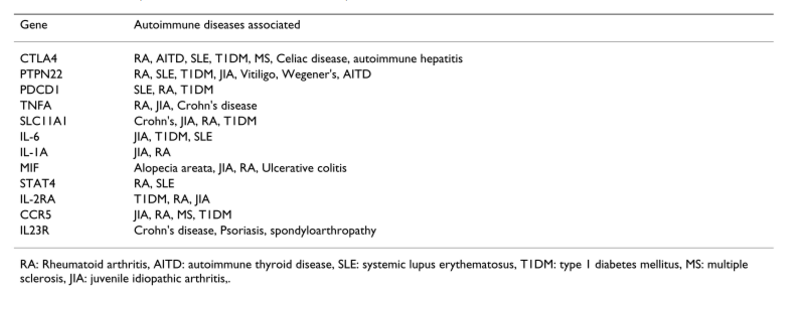

Several studies have shown that clinically distinct autoimmune phenotypes cluster in individuals and families. The data supports the hypothesis that common genetic factors might predispose to clinically distinct autoimmune phenotypes. There are genetic variants which influence susceptibility to multiple clinically distinct autoimmune disorders (Figure 10) (Prahalad and Glass, 2008).

Figure 10:This figure shows different examples of genes associated with multiple autoimmune diseases. Retrieved from (Prahalad and Glass, 2008).

Environmental Factors

The cause of JIA is assumed to be multifactorial, as in the case of most human autoimmune diseases. Unlike JIA, a healthy immune system consists of effector and regulatory mechanisms which are kept in balance. Therefore, the innate and adaptive immune systems closely interact. A genetically susceptible individual might develop a deleterious and uncontrolled response towards a self-antigen on exposure to an unknown environmental trigger. In JIA, it can lead to a self-perpetuating loop of activation of both innate and adaptive immunity, causing tissue damage (Prakhen, Albani, Martini, 2011).

Stress and Psychological Factors

The influence of stressful life events and psychological factors before the onset of JIA as a disease trigger has been studied. In a study by Henoch and colleagues which compared 88 children with JIA to 2952 geographically matched controls, results showed that children whose parents were unmarried due to divorce, separation, or death comprised 28.4% of the JIA population, compared to 10.6% in controls (Henoch, Batson, Baum, 1978).

Stress was also suggested as a contributing factor to the disease. It is a known stimulator to the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and thus increases the production of interleukin 6, which is one of the most important inflammatory cytokines in JIA (Roupe et al., 2000).

Although psychological factors and stress may play a role for the onset of JIA, more research needs to be conducted since past studies have had several methodological shortcomings (Berkun, Padeh, 2010).

Smoking

Smoking is the strongest known environmental risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in adults. The risk of RA from smoking has been showed by the number of shared epitope copies, which suggest gene-environment interaction. Specifically, the strongest known genetic risk factor for RA is a specific sequence of amino acids on HLA-DRB1 allele. In addition, the risk of developing RA from gene-environment interactions increases with the intensity of smoking (Liao et al., 2009).

All this suggests that smoke is a stimulator of the immune system and that the exposure to tobacco products during fetal life may influence the developing immune system of the fetus. This can lead to an increased susceptibility to infectious agents and thereafter, trigger arthritis as well as subsequent autoimmune diseases. Jaakkola and Gissler conducted a study assessing the relation between maternal smoking in pregnancy and the risk of inflammatory polyarthropathies, in particular JIA in the first years of life. 58 841 newborn Finnish children until the age of 7 were analyzed. Findings showed that there was a 2-fold higher rate of polyarthropathies during the first 7 years of life in children of smoking mothers, compared to non-smoking ones. In addition, the maternal smoking effect was found prevalent to girls, who experienced 6-fold greater likelihood for JIA compared to unexposed boys (Jaakkola and Gissler, 2005).

Infectious agents and JIA

Infectious agents are believed to be important environmental factors in the development of autoimmunity. An infectious agent may induce a cross-reactive immune response, thereby leading to inflammation provoked by antigen-presenting cells (APCs). This can lead to increased immunogenicity, priming of T cells and subsequent autoimmunity (Berkun and Padeh, 2009). A study by Carlens and colleagues showed that infections during the first year of life and factors related to size and timing of birth were associated with increased risk of developing JIA (Carlens et al., 2009) . However, more research needs to be conducted to understand the role of environmental factors on JIA.

Immunology of JIA

The overarching mechanism in all Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) subsets is the activation of the immune system. Different components are involved in each subtype and additional variation may exist within subtypes (Malmström, Catrina & Klareskog, 2016). Over the years, there has been considerable progress in understanding the immune-inflammatory reaction.

Auto-Immunity

Much of the scientific community believe the disease is initiated as a result of molecular mimicry between epitopes on antigens present on infectious agents and autoantigens. Molecular mimicry, by epitope spreading, overcomes tolerance mechanisms and results in autoimmunity. Over the years, two major subtypes of JIA have been identified on the basis of the presence or absence of auto-antigens: antibodies to citrullinated protein antigens (ACPAs) and rheumatoid factor (RF) (Malmström, Catrina & Klareskog, 2016).

Both subsets have different disease courses. The seropositive form usually means severe pathology. The seronegative forms of arthritis are not well understood and appear to be more heterogeneous compared to the seropositive variant (Malmström, Catrina & Klareskog, 2016).

Antibodies to Citrullinated Protein Antigens (ACPA)

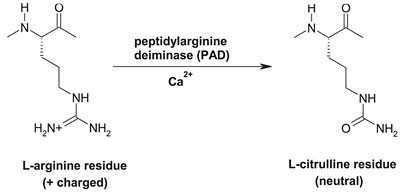

ACPAs are important for the diagnosis of JIA. These are the patient’s own antibodies which have been modified by citrullination, a process where proteins’ arginine residues are converted to citrulline post-translationally by the enzyme peptidyl arginine deiminase (PAD) (Figure 11). Once modified, the body recognizes its own antigens to be foreign, causing an immune response (Demoruelle & Deane, 2011).

Figure 11:This figure shows the process of citrullination. Retrieved from: https://www.hopkinsarthritis.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/08/round4-slide-12.jpg

Rheumatoid Factor (RF)

RF is an autoantibody derived from IgM that targets the Fc portion of IgG, specifically IgG1 to form immune complexes. These complexes are present in the synovial fluid along with IgG-producing B cells. Additionally, it can form complexes with complement proteins further promoting inflammation. Although RF has been associated with the pathogenesis of RA, it is possible for patients to develop arthritis without it (McInnes & Schett, 2011).

Interestingly, the literature suggests that RA-associated antibodies are present in the blood several years before joint inflammation signs are present. It is possible that anti-citrullination precedes the onset of joint inflammation which may be triggered in the lungs or other mucosal regions (Malmström, Catrina & Klareskog, 2016).

Inflammation

JIA is considered a T-cell mediated disease in which CD4+ T cells exacerbate inflammation in rheumatoid joints. Majority of the CD4+ T cells in joints appear to be of the Th1 type, with memory and activation markers. T cells in joints increase in number by recruitment, resistance to apoptosis and accumulation. For this process, cytokines are of importance.

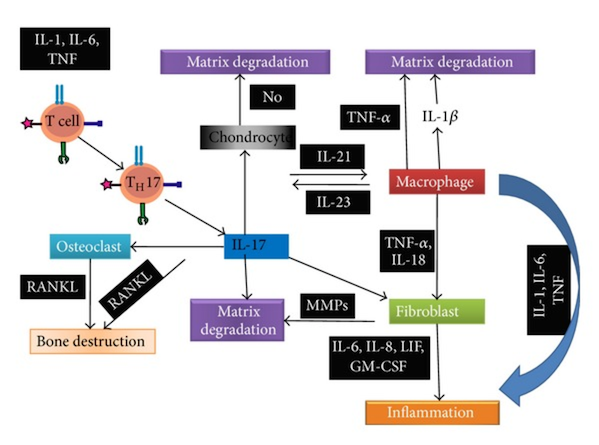

Cytokines are protein messengers that transmit signals from one cell to another by binding to specific receptors on the surface of cells. Both pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines, and mitogenic factors are produced, but proinflammatory mediators predominate during the active phase of disease.Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), IL-1, IL-6 and IL-17 are of key importance in the pathogenesis of inflammation in RA. IL-1 and TNFα are also key players in the regulation of mediators of connective tissue damage by synoviocytes, including matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and prostaglandins (Figure 12) (Nath Maini, 2010).

ACPAs may also bind to citrullinated proteins directly in the synovial membrane. Immune complexes between citrullinated proteins ,such as fibrinogen, and ACPA-igG can drive inflammation (including the production of IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor) by engaging both toll-like receptor (TLR4) and Fc receptors (Nath Maini, 2010).

Furthermore, these cytokines in combination with the cytokines monocyte colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and receptor activator of NF-κβ ligand (RANKL), activate osteoclasts leading to bone damage. TNFα regulates production of IL-1 and together these two cytokines induce rheumatoid inflammation and damage (Nath Maini, 2010).

Both ACPA- and RF-dependent events could contribute to the initiation and propagation of chronic synovial inflammation, and further synergize with T cell activation and enhance the local production of autoantibodies (McInnes & Schett, 2011).

Figure 12:This figure shows a summary of the pathogenic pathways in JIA. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Abdullah_Nahian/publication/263585727/figure/fig1/AS:202832654409738@1425370481906/Figure-illustrates-the-pathogenic-pathways-of-rheumatoid-arthritis-following-31-38.png

Bone Destruction

Osteoclasts, cells that line the bone and are responsible for the breakdown of bone tissue, have an important role in ACPA-dependent pathology. ACPAs generated from B cells found in the synovial fluid of patients with RA are able to promote osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption. The effects of these antibodies are mediated both by direct recognition and activation of Fc receptors on osteoclasts. Antibodies can exert a specific function on osteoclasts at the earliest stages of disease development and before joint inflammation appears (McInnes & Schett, 2011).

The literature suggests that osteoclasts and osteoclast precursors might be the major cell types that express citrullinated antigens on their surface in the normal non-inflamed bone and joint compartment, making precursor cells prime targets for circulating ACPAs. This feature is associated with the role of PADs but the exact role of PADs and citrullination in osteoclast differentiation is unknown (Malmström, Catrina & Klareskog, 2016).

Treatments

It is important to understand that treatment options for individuals with juvenile idiopathic arthritis focus primarily on managing the progression of the disease. While pharmacologic treatments do not cure the disease, specific types of physical therapy, drug therapy and surgical procedures aim to sustain the child’s physical and psychological integrity and minimizing side effects. In effect, a combination of the following types of intervention are most beneficial, however the process of recovery varies with the individual’s risk for disease progression. (Ravelli & Martini, 2007).

Physical Therapy

Heat or Cold

Physical treatments are often combined with other forms of treatment to ensure maximal efforts of juvenile idiopathic arthritis management. The application of heat to affected areas is soothing, as it increases blood flow and alleviates muscle or joint stiffness. Applying a cold pack or a compress numbs nerve endings associated with swollen joints, which reduces inflammation and swelling (AboutKidsHealth, 2017).

Exercise or Stretches

Prior to exercising, stretching or massaging tender areas allows for muscles to loosen and minimizes additional stress on affected areas. An important aspect regarding exercise for young children with arthritis is that it is done at a moderate intensity on a regular basis. Building muscle strengthens the support for affected joints, and regular exercise maintains a child’s body mass so that the child does not need to endure additional weight. It is important that children are not over exhausted by physical activity, as this could increase the pain and soreness (AboutKidsHealth, 2017).

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy assists in reducing stiffness, thus enabling a consistent continuous recovery over a long period of time. In addition to heat and ice physiotherapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation is a type of physiotherapy that disrupts pain signals from being transmitted to the brain in a non-invasive manner. A small device containing electrodes is attached to the skin on either side of the painful area. Pain relief tends to increase with prolonged use. (AboutKidsHealth, 2017).

Occupational Therapy

An occupational therapist assesses, treats and educates individuals and families affected by JIA. Their training focuses on assessing and treating fine motor skills, hand function and the application of hand splints (AboutKidsHealth, 2017).

Assistive Devices

Assistive devices provide support in completing many of the daily basic tasks. An individual who may have trouble holding a pencil when writing may use an angled writing surface to reduce the stress placed on his/her joints. Something as simple as replacing a notebook with a computer allows the individual to record the notes from class and complete a project at their own pace . A splint is another assistive device that can be customized to adhere with the mold of a child’s hand. This allows for a greater range of motion and reduced contractures, swelling stress and pain. In individuals with knee joint pain, splints can decrease flexion contractures (AboutKidsHealth, 2017).

Drug Therapy

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs include common painkillers such as ibuprofen and naproxen. Other commonly used NSAIDs include ketaprofen, diclofenac, and piroxicam (Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis, 2017). The NSAIDs are not used with the aim of preventing joint damage; they are rather used as a first line of treatment to manage pain and inflammation among children with JIA. NSAIDs work by interfering with prostaglandin synthesis through inhibition of the enzyme cyclooxygenase (COX), thus reducing swelling and pain (Kim, 2010). The most common side effects of NSAIDs are an upset stomach resulting in pain or nausea. However, some less common side effects include dizziness, headaches, bruising or rash (Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis, 2017).

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs)

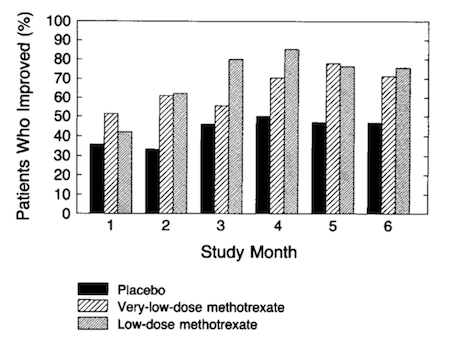

DMARDs are usually used as a second option if NSAIDs do not work. They are “slow acting” drugs that can take weeks to six months to work (Brescia, 2016). They act to treat JIA by slowing or stopping the immune system from causing the inflammation that destroys the joints (Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis, 2017). Since, it is the inflammation is what slowly destroys joint tissue over the years. Some common non-biologic DMARDs include methotrexate, leflunomide, and sulfasalazine (Harris et al., 2014). The most common non-biologic DMARD administered to children with JIA is methotrexate. Methotrexate is a folic acid analogue and it competitively inhibits with dihydrofolate reductase to interfere with purine biosynthesis and DNA production (Harris et al., 2014). Although the mechanism of action for methotrexate is not known, it is suggested that the extracellular adenosine release and its interaction with specific cell surface receptors may be related to the anti-inflammatory effects (Ramanan et al., 2003).

A study by Giannini et al. 1990 formed the basis for current use of methotrexate in JIA. They conducted a six-month randomized, double blind controlled multicenter study of 127 children with resistant juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. The results indicated that 63% of the group treated with 10 mg/m2, of MTX, improved compared with only 32% of those treated with 5mg/m2, and 36% of the placebo group (Giannini et al., 1990). Figure 13 shows a comparison of the three treatment category outcomes over a period of six months.

Biological Response Modifiers

Biological medications can be used to treat individuals who are resistant to commonly used antirheumatic drugs. Proinflammatory cytokines involved in the pathogenesis of JIA are the main components of biologic drugs. Etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab block anti-tumour necrosis factors (TNF-ɑ), thus reducing inflammation. Etanercept is administered through subcutaneous injections, and optimal dosage includes 0.4mg/kg twice a week or 0.8 mg/kg once a week. Infliximab and adalimumab are anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibodies that are administered through IV infusions and subcutaneous injections respectively. A concern with biologic drugs is immunosuppression, thus infections at the site of injection and respiratory tract develop. Furthermore, the reactivation of hepatitis B and tuberculosis are risks that individuals administered with anti-TNF-α agents endure (Ungar, et al., 2013).

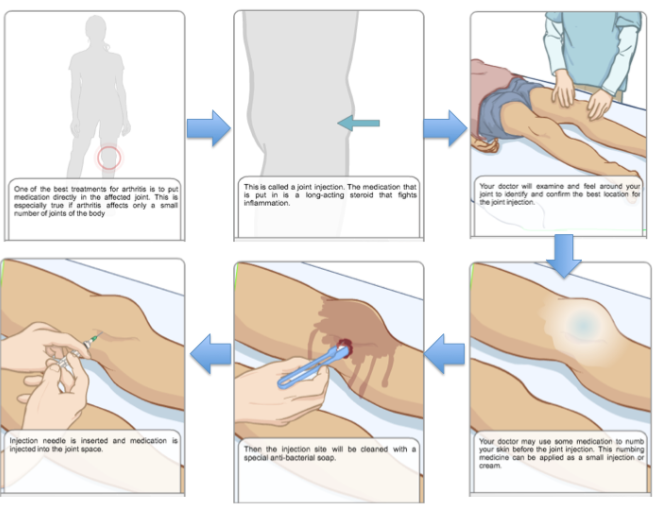

Corticosteroid Joint Injections

In the circumstance that a child does not show significant signs of recovery with the usage of other drug treatments, corticosteroids can be injected into the inflammatory joints. This method is effective as it minimizes the side effects by directly targeting the affected areas. This induces an immediate response within the course of a week. The three corticosteroids that are commonly used include Aristospan, Kenalog and Depo-Medrol. Please refer to Figure 14 to understand the process of injecting corticosteroids into the affected joints (AboutKidsHealth, 2017).

Figure 14:This figure depicts the process of injecting corticosteroids into affected joints in individuals with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. (Retrieved from http://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/En/ResourceCentres/JuvenileIdiopathicArthritis/TreatmentofJIA/MedicationsforJIA/Pages/CorticosteroidJointInjections.aspx)

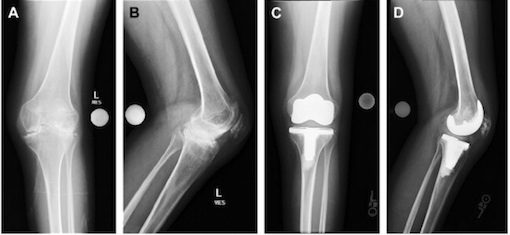

Surgical Treatment

Children must be of at least 6 years of age to be considered for surgery. Even when children are older than 6, surgery is usually very rare because there is a very low risk of a child developing joint damage that’s substantial enough to require some type of surgical intervention. Of the surgical interventions one that seem to be common for children is the soft tissue release of contractures. A contracture is a joint abnormally bent by shortened soft tissues in and around the joint. It involves cutting the excess tissue attached to the abnormally bent joint, and as the tissues are released the joint is able to return more to its normal position (Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis, 2017). The goal of soft tissue releasing is to (1) return the joint to a closer to normal position, and (2) increase range of motion. After soft tissue release surgery casts are usually worn for several weeks, followed by physiotherapy. Total joint replacement or arthroplasty is another form of surgery and it is practiced as a last resort for damaged joints. Figure 15 shows a patient’s knee after total knee replacement (Abdel & Figgie 2014). Total joint replacement is usually delayed until the child’s bones have stopped growing. This type of surgery can relieve pain and restore joint function but joints will not be restored to normal position. Other surgical methods include osteotomy, epiphysiodesis, synovectomy, and arthrodesis. Osteotomy is when a piece of a bone is removed to allow for better movement. Epiphysiodesis is carried out if there is specifically excessive growth, and the portion that is overgrown is removed. Synovectomy is rarely used in JIA cases, but it is the removal of the synovium to reduce inflammation. Lastly, arthrodesis is also rarely used, as it requires the fusing of two bones in the diseased joint to prevent joint movement.

Figure 15. This image shows the view before and after total knee replacement. Retrieved from (Abdel & Figgie, 2014).

Future Directions

The majority of children are treated adequately with a combination of treatments such as NSAIDs, corticosteroids and DMARDs available today. Yet, there are still some children, who are intolerant or resistant to these therapies, hence suffer from joint damage. For children who fall under this category, autologous stem cell transplantation seems to be a potential option (Brinkman et al., 2007). Autologous stem cell transplantation is a procedure where a person’s own stem cells to replace damaged cells (Autologous Transplants,n.d.). This method of treatment has only been tried on a few as thirty children. First, Wulffraat et al., reported positive results of autologous stem cell transplantation in four children (Brinkman et al., 2007).

References

Abdel, M. P., & Figgie, M. P. (2014). Surgical Management of the Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Patient with Multiple Joint Involvement. Orthopedic Clinics of North America, 45(4), 435-442. doi:10.1016/j.ocl.2014.06.002

AboutKidsHealth, and About.kidshealth@sickkids.ca. “Blood Tests and JIA.” Blood Tests and Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) - AboutKidsHealth. AboutKidsHealth, 16 Oct. 2012. Web. 02 Mar. 2017.

AboutKidsHealth -JIA Treatment of JIA. (2017). Retrieved February 20, 2017 from http://www.aboutkidshealth.ca/En/ResourceCentres/JuvenileIdiopathicArthritis/TreatmentofJIA/Pages/default.aspx

Ansell, B. M., Bywaters, E. G., & Lawrence, J. S. (1969). Familial aggregation and twin studies in Still's disease. Juvenile chronic polyarthritis. Rheumatology, 2, 37.

Autologous (Self) Transplants. (n.d.). Retrieved March 03, 2017, from http://www.leukaemia.org.au/treatments/stem-cell-transplants/autologous-self-transplants

Baum, J., & Fink, C. (1968). Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis in monozygotic twins: a case report and review of the literature. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 11(1), 33-036.

Berkun, Y., & Padeh, S. (2010). Environmental factors and the geoepidemiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Autoimmunity reviews, 9(5), A319-A324.

Brescia, A. C. (Ed.). (2016, April). Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Retrieved February 19, 2017, from http://kidshealth.org/en/parents/jra.html#

Brinkman, D. M., Kleer, I. M., Cate, R. T., Rossum, M. A., Bekkering, W. P., Fasth, A., . . . Vossen, J. M. (2007). Autologous stem cell transplantation in children with severe progressive systemic or polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis: Long-term followup of a prospective clinical trial. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 56(7), 2410-2421. doi:10.1002/art.22656

Carlens, C., Jacobsson, L., Brandt, L., Cnattingius, S., Stephansson, O., & Askling, J. (2009). Perinatal characteristics, early life infections and later risk of rheumatoid arthritis and juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 68(7), 1159-1164.

Demoruelle, M. & Deane, K. (2011). Antibodies to Citrullinated Protein Antigens (ACPAs): Clinical and Pathophysiologic Significance. Current Rheumatology Reports, 13(5), 421-430. doi:10.1007/s11926-011-0193-7 Giannini, E. H., Brewer, E. J., & Kuzmina, N. (1990). Arthritis. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics, 10(5), 697. doi:10.1097/01241398-199009000-00034

Gibson, W. M., Grokoest, A. W., & Larson, C. B. (1962). Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 5(2), 211-217.

Ginn, L. R., Lin, J. P., Plotz, P. H., Bale, S. J., Wilder, R. L., Mbauya, A., & Miller, F. W. (1998). Familial autoimmunity in pedigrees of idiopathic inflammatory myopathy patients suggests common genetic risk factors for many autoimmune diseases. Arthritis & Rheumatology, 41(3), 400-405.

Glass, D. N., & Giannini, E. H. (1999). Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis as a complex genetic trait. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 42(11), 2261-2268.

Goldstein, D. A., Horsley, M., & Ulanski, L. J. (2013). II, Tessler HH. Complications of uveitis and their management. Duane's Ophthalmology.

Grossman, B. J., & Mukhopadhyay, D. (1975). Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Current problems in pediatrics, 5(12), CO11-65.

Harris, J. G., Kessler, E. A., & Verbsky, J. W. (2013). Update on the Treatment of Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports, 13(4), 337–346. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11882-013-0351-2

Henoch, M. J., Batson, J. W., & Baum, J. (1978). Psychosocial factors in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 21(2), 229-233.

Jaakkola, J. J., & Gissler, M. (2005). Maternal smoking in pregnancy as a determinant of rheumatoid arthritis and other inflammatory polyarthropathies during the first 7 years of life. International journal of epidemiology, 34(3), 664-671.

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis - Genetics Home Reference. (2015, February 14). Retrieved February 20, 2017, from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/juvenile-idiopathic-arthritis#diagnosis

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis: Soft Tissue Release of Contracture - Topic Overview. (n.d.). Retrieved February 13, 2017, from http://www.webmd.com/rheumatoid-arthritis/tc/juvenile-idiopathic-arthritis-soft-tissue-release-of-contracture-topic

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis - Treatment Overview. (n.d.). Retrieved February 13, 2017, from http://www.webmd.com/rheumatoid-arthritis/tc/juvenile-rheumatoid-arthritis-treatment-overview#1

Kim, K. N. (2010). Treatment of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Korean Journal of Pediatrics, 53(11), 936–941. http://doi.org/10.3345/kjp.2010.53.11.936

Liao, K. P., Alfredsson, L., & Karlson, E. W. (2009). Environmental influences on risk for rheumatoid arthritis. Current opinion in rheumatology, 21(3), 279.

Malmström, V., Catrina, A., & Klareskog, L. (2016). The immunopathogenesis of seropositive rheumatoid arthritis: from triggering to targeting. Nature Reviews Immunology, 17(1), 60-75. doi:10.1038/nri.2016.124 McInnes, I. & Schett, G. (2011). The Pathogenesis of Rheumatoid Arthritis. New England Journal Of Medicine, 365(23), 2205-2219. doi:10.1056/nejmra1004965 Miller, M. L. (1994). Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Current problems in pediatrics, 24(6), 190-198.

Nath Maini, R. (2010). Rheumatoid arthritis. Oxford Textbook Of Medicine, 3579-3602. doi:10.1093/med/9780199204854.003.1905_update_001 Nelson, W. E., & Kliegman, R. M. (2016). Nelson Textbook of pediatrics. Philadelphia: Elsevier.

Prahalad, S. (2004). Genetics of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: an update. Current opinion in rheumatology, 16(5), 588-594.

Prahalad, S., & Glass, D. N. (2008). A comprehensive review of the genetics of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology, 6(1), 11.

Prahalad, S., Ryan, M. H., Shear, E. S., Thompson, S. D., Glass, D. N., & Giannini, E. H. (2000). Twins concordant for juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 43(11), 2611-2612.

Prakken, B., Albani, S., & Martini, A. (2011). Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The Lancet, 377(9783), 2138-2149.

Ramanan, A. V. (2003). Use of methotrexate in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 88(3), 197-200. doi:10.1136/adc.88.3.197

Ravelli, A., & Martini, A. (2007). Juvenile idiopathic arthritis. The Lancet, 369(3), 767-778. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60363-8

Rosen, P., Thompson, S., & Glass, D. (2002). Non-HLA gene polymorphisms in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clinical and experimental rheumatology, 21(5), 650-656.

“Rheumatoid Factor | ANA Test | Lab Tests | Arthritis Today.” Rheumatoid Factor | ANA Test | Lab Tests | Arthritis Today. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Mar. 2017.

Saurenmann, R. K., Rose, J. B., Tyrrell, P., Feldman, B. M., Laxer, R. M., Schneider, R., & Silverman, E. D. (2007). Epidemiology of juvenile idiopathic arthritis in a multiethnic cohort: ethnicity as a risk factor. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 56(6), 1974-1984.

Savolainen, A., Saila, H., Kotaniemi, K., KAIPIAINEN-SEPPAN, O., Leirisalo-Repo, M., & Aho, K. (2000). Magnitude of the genetic component in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 59(12), 1001.

Schaller, J. G. (1997). Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatrics in review, 18, 337-350.

Symmons, D. (2005). Commentary: Juvenile idiopathic arthritis—issues of definition and causation. International journal of epidemiology, 34(3), 671-672.

Ungar, W.J., Costa, V., Burnett, H.F., Feldman, B.F., & Laxer, R.M. (2013). The use of biologic response modifiers in polyarticular-course juvenile idiopathic arthritis: A systematic review. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism, 42(6), 597-618.

Van der Voort, C. R., Heijnen, C. J., Wulffraat, N., Kuis, W., & Kavelaars, A. (2000). Stress induces increases in IL-6 production by leucocytes of patients with the chronic inflammatory disease juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: a putative role for α 1-adrenergic receptors. Journal of neuroimmunology, 110(1), 223-229.

Wedderburn, L. R., Patel, A., Varsani, H., & Woo, P. (2001). Divergence in the degree of clonal expansions in inflammatory T cell subpopulations mirrors HLA-associated risk alleles in genetically and clinically distinct subtypes of childhood arthritis. International immunology, 13(12), 1541-1550.

William C. Shiel Jr., MD, FACP, FACR. (n.d.). Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) Symptoms & Treatment. Retrieved February 20, 2017, from http://www.onhealth.com/content/1/rheumatoid_arthritis_ra