This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis Powerpoint

Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis (JIA), also known as juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is a chronic form of arthritis that can be seen in children between the ages of 1-16 (Shiel, n.a). This disease refers to a group of conditions that pertain to joint inflammation (Genetics Home Reference, 2015). According to The Genetics Home Reference, “It is classified as an autoimmune disorder which means that the immune system malfunctions and attacks the body’s organs and tissues, in this case joints (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).” Through much research, it has been determined that there are seven types of JIA which are classified in accordance to their signs and symptoms, number of affected joints, results from medical tests and familial history (Genetics Home Reference, 2015). All seven types of JIA/JRA are chronic, thus individuals must develop coping methods that are long lasting and effective. <style float-right> </style>

Subtypes

Systemic JIA

Systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis causes inflammation in one or more joints, and its symptoms include high daily fevers that can last up to two weeks either preceding or accompanying the arthritis. A skin rash or enlargement of lymph nodes, liver or spleen are symptoms that differentiate this type of juvenile arthritis from other types (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Oligoarticular JIA

Oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis refers primarily to the inflammation of joints. Th is form of arthritis is prevalent in four or fewer joints in the first six months from when the disease was diagnosed. Depending on the onset of the condition, this form of arthritis can be divided into two subtypes. If the arthritis has not spread to more than four joints after six months, it is considered to be persistent oligoarthritis. If more than four joints are affected, it is classified as extended oligoarthritis (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Rheumatoid Factor Positive Polyarticular JIA

When inflammation is present in five or more joints within the first six months of the disease, it is considered rheumatoid factor positive polyarticular JIA. Patients with this condition have a positive blood test for proteins called rheumatoid factors. A rheumatoid factor is the amount of protein found in the blood that may attack healthy tissues in the human body. This type of JIA displays symptoms similar to the predominant types of arthritis in adults (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Rheumatoid Factor Negative Polyarticular JIA

This type of arthritis is similar to the rheumatoid factor positive polyarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis as it also affects five or more joints. As evident in its name, this type of JIA tests negative for the rheumatoid factor in the blood (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Psoriatic JIA

Psoriatic juvenile idiopathic arthritis is usually detected in combination with a skin disorder called ‘psoriasis’. This condition is understood by the red patches and irritated skin that are covered by flaky, white scales. Depending on the individual, some are affected by this skin disease prior to developing arthritis, and others notice the the skin condition while first developing arthritis. Other symptoms of this type of arthritis include abnormalities of the fingers and nails like uneven lengths and deformed fingers or vision problems (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Enthesitis-related JIA

Enthesitis-related juvenile idiopathic arthritis is classified by tenderness where the bone meets the tendon, ligament, or other connective tissue. This is usually accompanied by inflammation in joints and other related areas (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Undifferentiated Arthritis

This classification of undifferentiated arthritis is given to patients who have symptoms that are not explained by the descriptions of any of the above forms of JIA or who have fit the criteria for more than one of the given descriptions of JIA (Genetics Home Reference, 2015).

Epidemiology

The incidence of JRA in North America and Europe is researched to be 4 to 16 in 10,000 children (Genetics Home Reference, 2015). One in 1,000, or approximately 294,000, children in the United States are affected and the most common type of JRA in the United States is oligoarticular juvenile idiopathic arthritis (Genetics Home Reference, 2015). Females (for an unknown reasons) seem to be affected with JRA somewhat more frequently than males (Genetics Home Reference, 2015). However, in enthesitis-related JRA males are affected more often than females (Genetics Home Reference, 2015). The incidence of JRA varies from different populations and ethnic groups (Genetics Home Reference, 2015). [1]

In a study done by Saurenmann et al, questionnaires pertaining to ethnicity were distributed to patients with JRA and then followed up at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto (Saurenmann, 2007). When the data was collected, the relative risk of developing JRA was calculated and the results were compared with data from the age matched general population in the Toronto region (Saurenmann, 2007). The frequency at which JRA has been perceived shows that European descendants had about 69.7% of their patients diagnosed with JRA, which patients in the Toronto region has about 54.7% (Saurenmann, 2007). Statistically lower percentages were shown to patients who were of the black, Asian, or Indian subcontinental origin (Saurenmann, 2007). Kids from the European origin had a higher relative rate for developing any of the subtypes of juvenile arthritis, except oligoarthritis or psoriatic (Saurenmann, 2007). Patients of the Asian origin showed to have a greater chance of being diagnosed with enthesitis-related JIA while those of black or Native North American origin were more likely to develop polyarticular rheumatoid positive JIA (Saurenmann, 2007).

Symptoms & Diagnosis

JIA is diagnosed once symptoms are persistent for at least six weeks since the diagnosis (Shiel, n.a). Common symptoms of JIA include swelling, redness, and warmth of joints, however, many researchers and scientists attempt to formulate a criteria for the precise diagnosis of JIA (Nelson & Kilegman, 2016). The proposed criteria includes six requirements. Firstly, polyarticular or monoarticular arthritis must be present for at least six weeks or in the presence of the following: Iritis, rash, flexion contractures, ankyloses, muscle wasting, anemia, white blood cell count of 20000, cervical spine pain (Grossman & Mukhopadhyay, 1975). The second criteria is expressed as polyarticular or monoarticular arthritis for 6 weeks or less having the following characteristics: nonmigratory for at least 1 week, no symptomatic response to therapeutic blood levels of salicylate (20 mg/100 ml or above) preponderance of small joint involvement, involvement of the temporomandibular joints, morning stiffness (Grossman & Mukhopadhyay, 1975). Next, polyarticular or monoarticular arthritis for 6 weeks or less accompanied by pericarditis in the absence of endocarditis (Grossman & Mukhopadhyay, 1975). Fourth would be classified as constitutional symptoms known as any combination of fever, weakness, or weight loss (Grossman & Mukhopadhyay, 1975). The fifth criteria mention the elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Lastly the exclusion of all other diagnoses such as rheumatic fever, systemic lupus erythematosus, periarteritis nodosa, dermatomyositis, scleroderma, tuberculosis synovitis, leukemia, lymphoma, septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, sickle cell anemia and serum sickness (Grossman & Mukhopadhyay, 1975). This set of criteria was put together to ensure that the diagnosis of JIA was accurate and any symptoms shown couldn’t be associated with any other chronic disease. There are many symptoms that occur for JIA to be an option for diagnosis.

Flares

Flares are known as a classification of symptoms referring to joint pain and inflammation and can last from time periods ranging from weeks to months (Shiel, n.a). JIA patients tend to have periods of remission, where these symptoms aren’t as prevalent as they would have been in the past (Shiel, n.a). Following this grace period where pain is minimal, these symptoms can reappear and this is known as a relapse (Shiel, n.a). This notion of relapsing and remission varies from patient to patient and can also be a known trend with other symptoms as well (Shiel, n.a).

Fever

Fever is a common symptom for JIA and can be classified to many degrees. A fever in an individual who may have JIA can be recognized in three different states. “Intermittent fever with a daily single high spike of temperature to 104-105 ~ F, then returning down to a normal temperature. A remittent fever with a persistent elevation of 100-101 ~ F with occasional, somewhat irregular increases in temperature to 103-104 ~ F (Grossman & Mukhopadhyay, 1975). Lastly, low grade fever with periodic elevation of temperature to 100-101 ~ F, the elevations frequently occurring in the late afternoon or evening, the morning temperature being normal (Grossman & Mukhopadhyay, 1975).”

Morning Stiffness

Morning stiffness is a symptom that helps with the diagnosis of JIA. It constitutes as difficulty in moving muscles after a period of rest or inactivity (Miller, 1994). Individuals feel this pain in the morning after waking up from a night’s sleep and is not a result of pain (Miller, 1994). With activity and movement throughout the day it tends to disappear (Miller, 1994). It can vary in the time that it lasts from a few minutes to many hours (Miller, 1994). The degree to which morning stiffness occurs can also vary. It can be so sever that the child cannot move without help from another person (Miller, 1994). In these circumstances, the combination of a warm bath and an increase in activity will aid with the relief of the stiffness (Miller, 1994). Other times in the day where morning stiffness is prevalent is after a nap or sitting down for a prolonged period, however, this is usually not as sever as the morning occurrence (Miller, 1994). Morning stiffness is an important differential characteristic between JIA and rheumatic fever or septic arthritis and if it is noted to be happening, physicians and other medical assistance should take a further look into it (Miller, 1994).

Rheumatoid Rash

This symptom is extremely helpful when diagnosing JIA, especially in the acute onset of disease (Miller, 1994). According to Miller, “The characteristic rheumatoid rash is an erythematous, salmon-pink, evanescent, usually circumscribed macular (although occasionally maculopapular) eruption involving the trunk, neck, velar aspect to the arms, inner aspect of the thighs, buttocks and face. It may last for only a few minutes, a few hours or several years (Miller, 1994).” Again, the degree to which the rash may last varies, lasting from only a few minutes to many hours and appears strongly during times of high fever or during warm baths (Miller, 1994). Many times, the rash experienced in patients who have JIA can be mistaken for erythema annulare or marginatum, however, erythema annulare or marginatum does not spread to the face region which is prevalent in the rheumatoid rash of JIA (Miller, 1994).

Subcutaneous Nodules

Nodules have been observed in approximately 10% of children who have been diagnosed with JRA and can appear subcutaneously (Miller, 1994). Characteristics of nodules include varying in sizes (from a few millimeters to several centimetres in diameter) nontender, no attachment to overlying skin and therefore move freely under the skin (Miller, 1994). Many times, they are found over the extensor tendon sheath of the hands, specifically over the metacarpophalangeal, proximal interphalangeal and distal interphalangeal joints (Miller, 1994). They are also found near the olecranon process of the elbow, over the anterior tibial surfaces and around the wrists and when fever is prevalent in the patient, nodules are found along the tendons of the erector spinae group and over the aponeurosis of the scalp (Miller, 1994).

Uveitis Eye condition

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis can also lead to an eye condition called uveitis, also named iridocyclitis or iritis (Goldstein et al, 2013). This may or may not lead to any symptoms arising, however, some symptoms of this condition are red eyes, eye pain, vision changes and sensitivity to light (Goldstein et al, 2013). Uveitis is known as the swelling and irritation of the uvea, which is the middle layer of the eye (Goldstein et al, 2013).

Blood Tests for JIA

Rheumatoid factor (RF) is a protein that is produced in the blood in some forms of arthritis (SickKids, 2012). This is more common in adults with rheumatoid arthritis, however, it is found in 5% of children with JIR (SickKids, 2012). The RF test is a test that is used to detect and measure levels of a specific antibody directed against the blood component immunoglobulin (Arthritis Foundation, 2016).

Liver function test (LFT) is a test that determines if the liver is healthy and working normally (Arthritis Foundation, 2016). There are many medications that are used to treat arthritis such as, methotrexate that are metabolized in the liver (Arthritis Foundation, 2016). These medications may play a role in overburdening the liver and therefore doctors may order an LFT in order to determine the medication that is causing the damage (Arthritis Foundation, 2016).

Antinuclear antibody (ANA) is a test used to look at autoantibodies in the blood (SickKids, 2012). Autoantibodies are proteins in the immune system and is also a good indicator to whether children and teenagers with JIA have an increased risk of eye disease (SickKids, 2012).

Complete Blood Count (CBC) measures three types of cells that are found in the blood; red cells (carry oxygen), white blood cells (fight infection) and platelets (cause blood clots) (Arthritis Foundation, 2016). This test is useful when discovering more about the condition, for example, kids with low red blood cell counts are usually ones who are suffering from JIA (Arthritis Foundation, 2016).

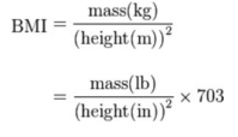

Figure 4: BMI Calculation Equation from http://www.heartnewslinks.com/editors-blog/body-mass-index-bmi-bad

BMI in children

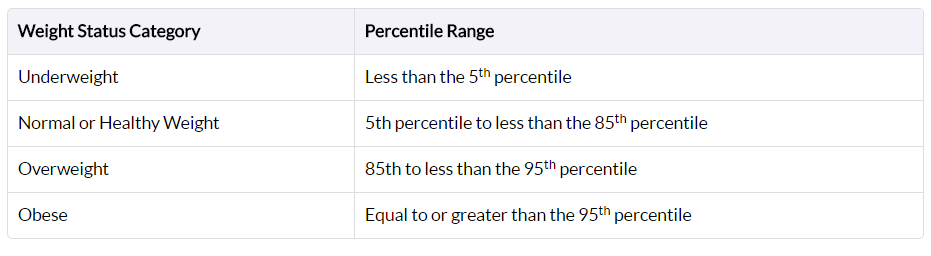

Obesity is defined differently for children and teens compared to adults due to the fact that they are still growing (Figure 5). BMIs for this cohort compare their height and weight against growth charts that take age and sex into account, since males and females in this cohort usually mature at different rates.

Their BMI is referred to as BMI-for-age percentile, meaning the child’s BMI is compared with other children of the same sex and age who participated in national surveys that were conducted from 1963-65 to 1988-94.[4]

Figure 5: BMI-for-Age Percentile Ranges for Children from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html>

BMI Limitations

Variance in Asian Populations

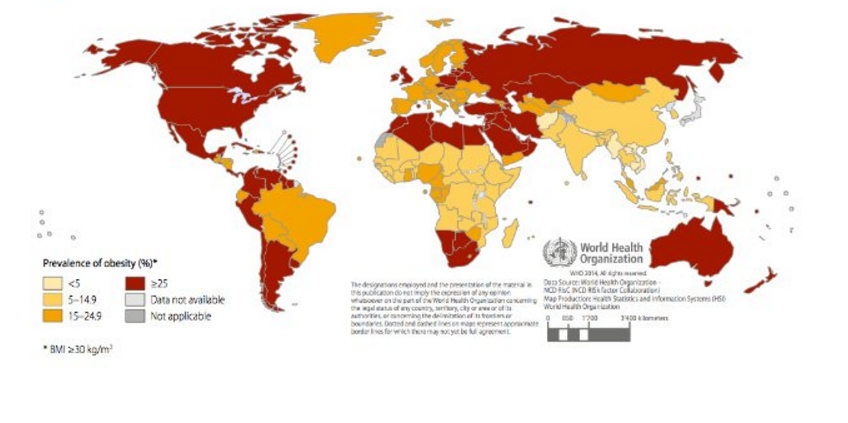

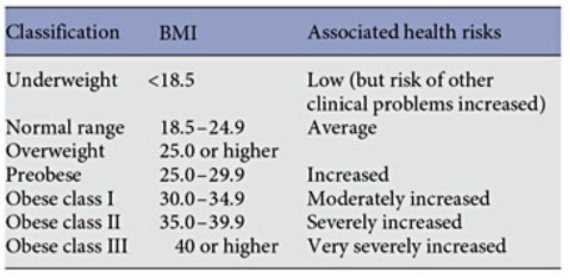

There were some debates on whether there is a need for developing different BMI cut-offs for different ethnic groups due to increasing evidence that the associations between BMI, percentage of body fat, and body fat distribution differ across populations and therefore, the health risks increase below the cut-off point of 25 kg/m^2 that defines overweight in the current WHO classification. The WHO Expert Consultation study concluded that the proportion of Asian people with a high risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease is substantial at BMI's lower than the existing WHO cut-off point for overweight, but the cut-off point for observed risk varies in different Asian populations and for high risk. Therefore they concluded that the current WHO BMI cut-off points should be retained as the international classification.[2]

However, overtime, the BMI (weight/height) became a universally accepted measure of the degree of overweight, and now, identical cutoffs are recommended.[2]

BMI in Athletes

Although the BMI is a good gauge of an individual’s level of fat it is problematic in the case of individuals with higher bone and/or muscle mass. Athletes and individuals with jobs that require physical fitness are often wrongly categorized as overweight due to the their muscle mass.[5]

Causes and Risk Factors

Obesity does not always have a particular cause and effect. There are a plethora of factors that can be associated with obesity and impact the way an individual’s body reacts. The following are:

Energy is Unbalanced

An absence of energy balance is often considered to be the major cause of obesity. Energy balance means that the energy going in, in the terms of calories, equals the individual’s energy out, such as energy that the body uses for things like breathing, digesting, and being physically active. To maintain a healthy weight, the energy needs to be roughly balanced over time [6].

Lack of Active Lifestyle

Generally, developed nations’ citizens are not very physically active. Individuals rely on cars instead of walking, encounter fewer physical tasks at work, or remain at home because of modern technology and conveniences. People who are inactive are more likely to gain weight because they do not burn the calories that they take in from food and drinks. An inactive lifestyle also raises the risk for heart disease, high blood pressure, diabetes, and other diseases [7].

Environment

Sometimes the environment inhibits healthy lifestyle habits and encourages obesity. Some reasons include: lack of neighbourhood sidewalks and safe places for recreation, work schedules are time consuming, oversized food portions, lack of access to healthy foods, and food advertising focused on high-calorie, high-fat snacks and sugary drinks [8].

Genes and Family History

Obesity tends to run in families. The chances of being overweight or obese are greater if 1 or both of the individual’s parents are overweight or obese. Genes also may influence the amount and location of excess fat one stores in their body. Since families usually share food and physical activity habits, there is a link between genes and the environment [9].

Health Conditions

Hormone problems may also cause an individual to become overweight and obese. This includes illnesses such:

Hypothyroidism: A condition in which the thyroid gland does not make enough thyroid hormone. The lack of thyroid hormone slows down the metabolism and causes weight gain [10].

Cushing's syndrome: A condition affecting the body's adrenal glands. The glands make too much of the hormone cortisol which alters nutrient intake. Cushing's syndrome also can develop if a person takes high doses of certain medicines for a long time. Patients have upper-body obesity and fat around the neck with thin extremities [10].

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS): A condition that affects about 7% of women of childbearing age. These women often are obese, have excess hair growth, and have reproductive issues along with and other health issues. These problems are caused by high levels of hormones called androgens [10].

Medicines

Certain medicines may cause gain weight. These medicines include specific corticosteroids, antidepressants, and seizure medicines. These pharmaceuticals can slow the rate at which the body burns calories, increases appetite, or causes the body to retain water [11].

Emotional Factors

Some people eat more than usual when they are bored, angry, or stressed. Over time, overeating will lead to weight gain and may cause overweight or obesity [7].

Smoking

It is not uncommon to see people gain weight when they stop smoking. Nicotine raises the rate at which the body burns calories, therefore less calories are burned when one ceases from smoking [12].

Age

As we age, muscle is lost, especially if one is less active. Muscle loss can slow down the rate at which the body burns calories. Midlife weight gain in women is mainly due to aging and lifestyle, but menopause also plays a role. Many women gain about 5 pounds during menopause and have more fat around the waist than before [13].

Pregnancy

Women gain weight to support their child’s development. After giving birth, some women find it hard to lose the weight. This may lead to overweight or obesity, especially after a few pregnancies [14].

Lack of Sleep

Lack of sleep increases the risk of obesity. People who sleep fewer hours also seem to prefer eating foods that are higher in calories and carbohydrates, which can lead to overeating, weight gain, and obesity. Additionally, sleep helps maintain a healthy balance of the hormones that make you feel hungry or full. Sleep also affects how the body reacts to insulin, the hormone that controls your blood glucose level. Lack of sleep results in a higher than normal blood sugar level, which may increase the risk for diabetes [15].

Pathophysiology

Adipocyte Development and Metabolism

Obesity can be characterized by the excessive accumulation of adipocyte cells forming deposits of adipose tissue. Individuals with a healthy metabolic activity and a normal BMI undergo the process of lipolysis, which is the breakdown of lipids. Lipolysis is regulated in the process of 𝜷₁ and 𝜷₂ adrenergic receptors (ARs) signalling cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) dependent protein kinase to initiate the phosphorylation of perilipin and hormone-sensitive lipase. Adipocytes express elevated levels of α₂ adrenergic receptors, which inhibit the expression of cAMP, thus preventing lipolysis. Furthermore, reduced lipolytic regulation is evident in hypertrophic subcutaneous fat cells, as they contain more α₂ ARs in comparison to 𝜷₁ and 𝜷₂ ARs. Defects or polymorphisms in the 𝜷₂ AR gene may also impede in the process of lipid breakdown [16].

In events of inadequate caloric intake, adipocytes allow excess energy to be stored as triacylglycerol. Non-esterified fatty acids (NEFAs) are primarily involved in insulin signalling, however they are also released when triacylglycerol stores undergo lipolysis. While triacylglycerol synthesis and lipolysis occur in a balanced manner under normal conditions, NEFAs are increased in obese individuals, thus posing a risk for Type 2 diabetes [16].

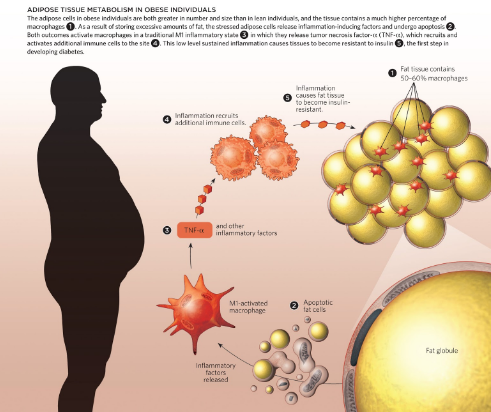

The secretory activity of adipocytes plays a huge role in regards to hormonal and metabolic activity that takes place. Adipose cells are increased in size and number in obese conditions, which initiate an immune response. The fat cells release pro-inflammatory adipokines that recruit macrophages to the site. Following this, Tumour Necrosis Factor- alpha (TNF-α) is released and additional immune cells are brought to the site. This constant state of inflammation causes insulin resistance. This is why diabetes is often comorbid with obesity [17]. This sequence of events is depicted in Figure 7.

When analyzing other inflammatory factors, it is evident that increased concentrations of the adipokine Interleukin-6 (IL-6) are positively correlated with increased fat mass and BMI. Furthermore, IL-6 is increases post-exercise with increased NEFAs, thus proposing a correlation between the adipokine and lipid mobilization [16].Monophosphate activated protein kinase (AMPK) enables the oxidation of fatty acids during muscle contraction. AMPK is regulated by the hormone adiponectin, which induces insulin-sensitivity. In individuals who are obese, the concentration of adiponectin is reduced, as individuals with symptoms of diabetes are resistant to insulin [16].

Hormone Regulation

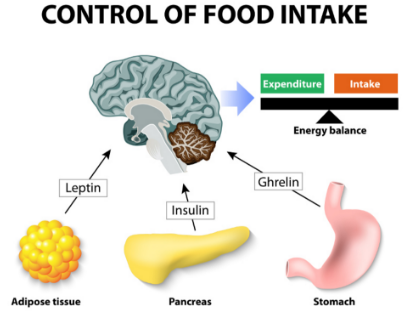

The hormonal regulation of insulin, leptin and ghrelin is affected in obese individuals. Hormonal imbalances cause physiological changes that impede on appetite suppression and insulin sensitivity. Figure 8 shows human hormones and food intake.

Insulin

Insulin is a hormone secreted by the 𝜷 cells in the pancreas [18]. They regulate glucose levels by storing glucose into muscle, fat, and liver cells. In obese individuals, we see a high incidence of insulin resistance, therefore insulin is unable to regulate glucose levels. Under normal physiological conditions, food is broken down into glucose post-consumption, and the pancreas secretes appropriate levels of insulin to maintain homeostatic levels of plasma glucose. Due to the fact that insulin displays insensitivity in obese individuals, the glucose absorbance is very low. Since the cells do not have energy, appetite-suppression is hindered and overeating occurs. The detrimental effects of this include an excessive blood glucose and insulin release, thus making obese individuals more susceptible to Type 2 diabetes. [18].

Investigating the molecular mechanism underlying insulin resistance is important towards understanding the relationship between insulin and obesity. There are many mechanisms through which insulin is able to promote the accumulation of fat in adipocytes, such as the early differentiation of preadipocytes to mature adipocytes, the unregulated transportation of glucose, the upregulation of lipogenesis, and the downregulation of lipolysis[19].

Leptin

Leptin is an appetite-suppressing peptide hormone that is secreted by adipocytes[20]. In obese individuals, there is a greater mass of adipose tissue, which directly correlates with a greater secretion of leptin. Theoretically, when there is more leptin, individuals should consume less, because the hormone is appetite suppressing. However, there is a higher appetite-stimulating effect in obese individuals. This suggests that individuals who are obese display leptin resistance.

A study conducted by Kazmi et al.(1996) investigated leptin concentrations in a sample of a Rawalpindi population. There were three sampling groups—health obese, overweight and non-obese. According to the results, the mean serum leptin concentration for the obese group was 52.8 ug/mL and 6.3 ug/mL for the non-obese group. The results of this study concluded there is certainly a positive correlation between the Body Mass Index and leptin concentrations in individuals [21].

Ghrelin

Ghrelin is an appetite-stimulating hormone secreted primarily by the stomach during times of low caloric intake [20]. It signals individuals to increase their food intake and promote fat storage. The concentration of ghrelin is expected to be higher with obesity, because it would account for the increased food intake in cases of obesity. However, experimental evidence shows that Ghrelin concentrations are actually much lower in obese individuals. To investigate the role of ghrelin in obese pathology, Tschop et al. (2001) conducted a study where the plasma ghrelin concentrations of lean and obese individuals were measured. The plasma ghrelin concentrations of obese individuals were much lower than in lean individuals [22]. There seemed to be a negative correlation between plasma ghrelin concentrations and fat mass.

The body’s instinctive shift for homeostasis could account for the downregulation of plasma ghrelin in obese individuals. Since ghrelin and leptin display antagonistic properties, it would not be possible for there to be high concentrations of both hormones. High leptin concentrations could account for low concentrations of ghrelin [20]. The exact mechanism through which this happens is yet to be elucidated by research.

Genetic Predisposition

When assessing the heritability of obesity, it has a numerical association of 0.7, which is fairly high relative to heritability in schizophrenia (0.81) and autism (0.9). In the case of rare familial obesity, gene defects occur in appetite regulation. Variants in the leptin-melanocortin pathway result in about 5% of morbid human obesity. Common polygenic obesity is characterized by the human obesity gene map. When performing a closer analysis of some of the key factors involved in obesity, Pre-B cell colony enhancing factor (PBEF1), which is secreted by lymphocytes, is expressed by adipocytes. Presently, it is referred to as Visfatin [23].

Due to the interconnectedness of genes, it can be difficult to address conflicting effects of similar genetic factors. Ghrelin binds to the growth hormone secretagogue receptor (GHSR), and initially, variants of GHSR were evident in common obesity and rare familial obesity. More recent studies show a negative correlation between GHSR variants and obesity. It is hypothesized that these effects could be due to obestatin, which is a hormone that regulates appetite in the opposite way that ghrelin does [23].

Having the ability to detect the genetic basis for obesity provides therapeutic solutions that can combat symptoms of obesity. A variety of biomarkers have been identified as factors involved in obesity. These biomarkers are used to differentiate between types of obesity, provide insight on the associated comorbid diseases, genetic susceptibility and explain the implications of the interaction between two or more factors [23].

Areas of research pertaining to molecular genetics are expanding the scope of genetic predispositions involved in obesity. As of October 2005, 244 mutated genes or transgenes causing phenotypic changes in weight and adiposity are identified. The human obesity gene map indicates that 176 human obesity cases can be linked to 11 specific genes, and 50 loci pertaining to human obesity are linked to Mendelian syndromes [24]

The gene map (Figure 9), includes all obesity-related genes and quantitative trait loci identified from the various lines of evidence reviewed in the paper. It is further explained and categorized into the 5 categories, where information pertaining to the mouse chromosome, mouse gene, human chromosome, human homolog, statistical analyses of variance, gene description, details pertaining to its role in obesity and more is provided. Areas of research pertaining to molecular genetics are expanding the scope of genetic predispositions involved in obesity [24].

Figure 9: Human obesity gene map, updated in 2005. From http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/doi/10.1038/oby.2006.71/full

Treatments

Goals of Weight Loss and Management

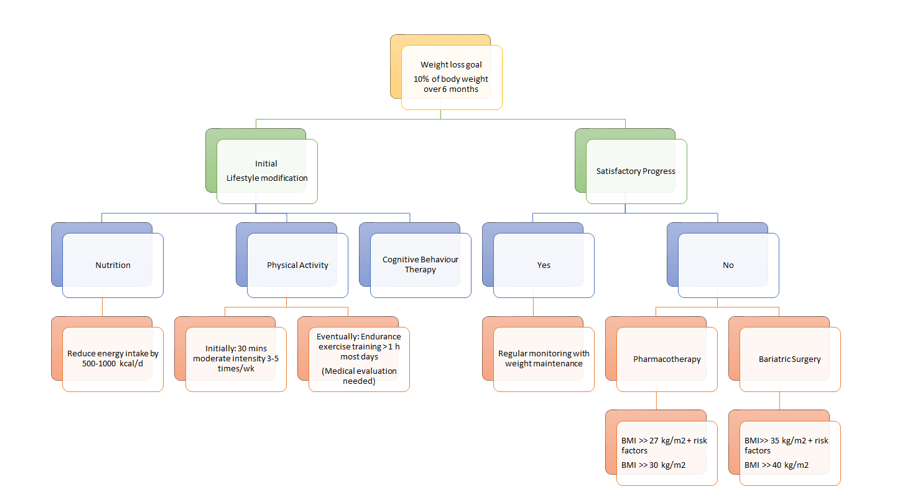

When undergoing weight loss therapy, practice guidelines issued by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and the North American Association for the Study of Obesity recommend an initial weight loss goal of approximately 10% from baseline over a period of 6 months of therapy [25].

A weight loss of 10% has the potential to improve glycemic control, blood pressure control and lipid levels, especially in individuals with Type 2 diabetes or hypertension. Additionally, it might help to reduce symptoms from comorbidities, such as gastroesophageal reflux and osteoarthritis. If weight loss is maintained over a long period of time, adverse clinical outcomes, such as myocardial infarction, stroke and cardiovascular-related deaths, can be reduced [26].

Intervention

For the optimal weight loss and health benefits, it is important to adopt lifestyle modifications, such as dietary therapy, physical activity and cognitive behaviour therapy. Typically, health care practitioners recommend their patients to pursue the lifestyle modifications for 6 months. Thereafter, clinicians assess whether they have reached the weight loss goal of 10% from baseline estimates. If patients have attained a satisfactory progression upon evaluation, it is recommended that they maintain their lifestyle modifications for sustainable weight loss results. Regular monitoring is a crucial aspect of ensuring a healthy lifestyle, as the influences of side effects must also be considered. In the case that patients have not attained their recommended weight after 6 months, health care practitioners typically recommend pharmacotherapy and/ or bariatric surgery to achieve their weight loss goal. The most conclusive results are seen when either pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery are used in conjunction with lifestyle modifications [25].

Diet

The first component of lifestyle modifications to treating obesity is undergoing dietary therapy (Figure 10). When assessing diet management in obese patients, weight reduction is highly dependent upon energy intake in comparison to energy expenditure [27].

According to a study conducted by Poirier and Despres (2001), it has been concluded that approximately 1 pound of mass can be lost within a week without any changes being made to the level of physical activity [27]. There are various types of diets that an individual can choose to pursue. Each type of diet is subjective to the patient, therefore it can produce differing results. Three diets that are typically suggested to obese patients are the low carbohydrate diet, the low-fat diet and the high protein diet.

The low carbohydrate diet is consists of a reduced carbohydrate consumption [28]. Long-term studies have shown that low carbohydrate diets produce significant results at the 3 and 6 month points. However, results become insignificant at about a year onwards [29]. When examining the weight reduction that high protein diets produced, the results were indifferent [29]. Patients were losing a significant amount of weight up until about a year and then the results started to decrease [29]. Studies about the low-fat diet have shown that patients saw a significant weight reduction for about three years and then results were insignificant [30].

Although all three of these diets show promising results, the low carbohydrate and high protein diets show short term effects, while the low fat diet seems to display long term fat reduction. In conclusion, it is important to note that many individuals are susceptible to regaining their weight, thus a sustainable lifestyle is integral. Managing weight loss through dietary means can be difficult, however it can be made easier when incorporating physical activity into the daily routine.

Weight Loss Programs

Due to the vast technological advances of our time, there are many weight loss programs available that are highly accessible. Although there are a wide variety of programs to choose from, it is always encouraged to keep in mind that not every weight loss program will produce the same kinds of results for everyone. It is always important to consult with a family physician when trying to find a weight loss program that will have a positive effect on a personal weight reduction.

Some examples of weight loss programs that are available for further investigation are listed below:

The Paleo Diet: It works to incorporate whole foods, lean protein, veggies, fruits, nuts, and seeds and encourages to stay away from foods with sugars, dairy and grains.

The Vegan Diet: It is an ‘extreme’ vegetarian diet that works to eliminate dairy, eggs, and animal derived products, such as gelatin, honey, whey, and vitamin D3.

The Low Carbohydrate Diet: It encourages individuals to eat an unlimited amount of protein and fat, while completely eliminating carbohydrates.

The Ultra Low-Fat Diet: It consists of a diet where 10% or less calories come from fat. This diet is almost entirely made up plant based food items, with a very limited intake of animal products.

The Zone Diet: This diet encourages participants to balance each meal with one third of protein, and two thirds of fruits and veggies. A small amount of fat that comes from natural and healthy sources, such as avocado, almonds, or olive oil can also be consumed.

Intermediate Fasting: This diet challenges its participants to fast during portions of the day, while restricting the calorie intake during the times you do choose to eat. This diet is most efficient when you aren’t overeating during the times where the fast has been broken.

There are a few options when trying to reduce weight loss. All of the diets that are listed above prove to have a positive impact on weight reduction. However every diet has its consequences. When the body is restricted from having certain kinds of foods, nutrients, minerals and vitamins are compromised. For example, if an individual were to go on the paleo diet, the restriction of whole grains and dairy prevents individuals from consuming certain vitamins. A family physician or a dietician would be able to provide the most representative diet plan for each individual [31].

Physical Activity

The second component of the lifestyle modifications approach to treating obesity is to be physically active. The purpose behind weight loss and management programs is to stop future weight gain, decrease body weight and permanently maintain a lower body weight [32]. Maintaining a physically active lifestyle is known to be key to a long term weight maintenance, because it increases the energy expenditure through caloric deficit [33]. When incorporating physical activity into a daily routine with hopes of maintaining the reduction of body weight, it is important to remember that different training modalities such as walking, cycling and swimming can have a different impact on different individuals [34].

When involved in physical activity, many adaptive responses take place, which cause a more efficient system for oxygen transfer to muscle [32]. In addition, reduced adipose tissue mass representing an important mechanical advantage, allows better long-term work [32]. Physical training helps counteract the permissive and affluent environment that predisposes reduced-obese subjects to regain weight [32]. Many studies have recommended thirty to forty-five minutes of moderately intensive physical activity, to be done 3-5 times a week [35]. In particular, public health interventions have promoted walking as a physical activity, since it is safe, accessible and a low intense aerobic exercise that results in high fat loss [32]. Losing weight through physical activity can be very difficult, especially for obese patients and therefore, it is important to set realistic weight loss goals of about 0.5-1 pound per week, with the assistance [32]. Because it may seem like small steps are made in weight reduction while working out, it is important for patients to remain determined and persevere to reach their goals [32]. Keeping a positive attitude during this process can be very difficult and so, it is extremely important for the patient to have one-on-one interaction between the clinician or healthcare professional on a regular basis [32].

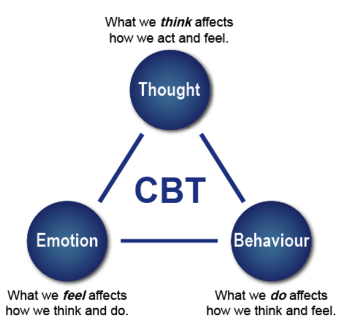

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy

The third component of lifestyle modifications is to undergo cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) to assess one’s current habits and identify factors, stressors or situations that may trigger one’s overeating habits and contribute to their obesity (Figure 11). With a CBT approach, patients suffering from obesity can get help through counseling, support groups, as well as adopt the family-based approach [25,26].

The purpose of the CBT treatment is not to eliminate a psychiatric disorder but to change eating and exercise behaviours [36]. This intervention aims to educate individuals on how to change problematic behaviours. Firstly, CBT is based on the cognitive conceptualization of the processes that lead to overeating. Specifically, thoughts and thinking patterns that are considered central to the problem. Secondly, CBT is focused on altering the cognitive and behavioural mechanisms that maintain the problem behaviour. Lastly, CBT uses both cognitive and behavioural techniques to maintain healthy mechanisms [37]. The diagram here shows different components that contribute to CBT.

Counselling is one way a patient can undergo CBT. It can either be delivered on a one-on-one basis, or in a group setting of approximately 10 participants with a trained healthcare professional [38,39]. A study conducted by Renjilian and colleagues comparing the two treatment modalities concluded that participants who were randomized to receive group-based therapy lost more weight after 26 weekly sessions compared to those who were treated individually. Specifically, those receiving group therapy lost about 11 kg after 26 weekly sessions, in comparison to 9 kg for those who were individually treated [40].

In addition to counselling, having a support network is important. This is especially true if the individual is undergoing drastic changes. Receiving encouragement from family, friends and health care practitioners can be very motivating during challenging times of the weight loss and maintenance programs. Furthermore, patients can also join support groups with other people undergoing weight loss [25].

Family-based obesity treatment has also been proven to be a very effective and sustainable approach, especially when treating pediatric obesity. The role of this treatment is to target eating and activity change in both child and parent. Programs using this approach teach parents behavioural skills to facilitate child behaviour change and utilize family resources to improve the efficacy of childhood obesity treatments. Simultaneously treating the child and parent helps create positive relationships between them as they both aim to reach their weight loss goal together [41,42].

Pharmacotherapy

The Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management and Prevention of Obesity in Adults and Children recommends that in addition to lifestyle modifications such as dietary changes, physical activity and behaviour therapy, overweight individuals with BMIs greater than 27 kg/m^2 but with life threatening diseases, or obese individuals with BMIs greater than 30 kg/m^2 can undergo pharmacotherapy [2].

A meta analysis investigated 21 randomized control trials (RCT) that involved a total of 11 533 participants using either one of the two drugs: orlistat or sibutramine, or a placebo. These RCTs had a follow-up period of at least 1 year in obese and overweight adults.

Olistat functions as a gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor and reduces fat absorption by approximately 30% (Figure 12). Patients can use it for up to two years [43]. On the other hand, sibutramine functions as a serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor which induces weight loss through enhanced satiety and increased basal energy expenditure. Sibutramine is approved for clinical use for up to 1 year [44].

Pharmacotherapy trials comparing the effect of combined dietary and pharmacotherapy treatment to dietary treatment alone, showed that patients who received treatment underwent a greater weight loss compared to those who only had a reduced-energy diet. This was when orlistat or sibutramine was combined with a reduced-energy diet. More specifically, the long term weight loss for those receiving combined therapy of dietary and pharmacotherapy was about 6 to 7 kg, compared to about 2 to 3 kg for those who received dietary therapy only [26].

Maintenance of weight loss

Studies that assessed orlistat therapy for at least 2 years and up to 5 years showed that weight loss attained by year 1 was better maintained over the subsequent 3 years in patients who received ongoing drug therapy. Specifically, Davidson et al. showed that patients who had ongoing treatment of orlistat for 2 years were associated with less regain of weight loss (32%) compared with diet only therapy (63%) [45].

In addition, a 2-year study conducted by James et al., showed that 43% of patients who received 6 months of weight loss induction using diet-only therapy, followed by sibutramine-diet therapy had better maintained 80% or more of weight loss, compared to only 16% in the diet-only group who received diet-placebo therapy [46]. This shows that combined therapy is more effective than diet-only group.

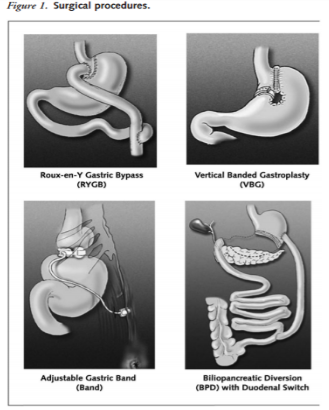

Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric surgery is a treatment method that is considered for adult patients who have a BMI over 35kg/m^2 with severe comorbid diseases such as life-threatening cardiopulmonary problems, severe sleep apnea, or severe diabetes mellitus, or for those in the severely obese category with a BMI greater than 40 kg/m2. For teenagers, the Canadian Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management and Prevention of Obesity in Adults and Children recommends that bariatric surgery be limited to an appropriately trained and experienced surgical team. After 6 months of using lifestyle modifications, healthcare practitioners assess the health of the patient and evaluate whether a satisfactory progress of weight loss or goal of 10% of body weight has been reached. In the case that satisfactory progress or goal has not been achieved, physicians will consider the eligibility of patients to undergo bariatric surgery. This is only considered if other nonsurgical weight loss attempts have failed. The goal of bariatric surgery is to relieve a patient suffering from obesity from his or her morbid body weight, improve their comorbidity and improve their quality of life. There are different surgical procedures (Figure 13). It is important to note that this treatment option requires lifelong medical surveillance [26].

A study on obese Swedish patients investigated the conventional, nonsurgical management with surgery for morbid obesity in 2004 found that surgical management is more efficacious than medical management. Patients who received surgical treatment produced greater weight loss, improved lifestyle and dramatic improvement of comorbid disease. At 10 years of follow-up, the surgical cohort showed that they maintained a weight loss greater than 16.1% of their original body weight. In contrast, those who received the conventional, nonsurgical management had a weight gain of 1.6%. This 16.3% weight difference demonstrates the effectiveness and maintenance of surgical procedures [47].

Summary of Treatment Options

As seen in figure 14, there are different approaches to treating obesity. First, it is important to set a weight loss goal to reduce body weight by approximately 10% from baseline during the first six months of treatment. Healthcare practitioners typically recommend their patients to first undergo lifestyle modifications: proper nutrition, physical fitness, and cognitive behaviour therapy. After six months of treatment, healthcare practitioners will assess the patient’s progress and determine whether satisfactory progress or weight loss goal has been reached. In the case that it has been reached, the patient would be closely monitored on a regular basis to make sure that their weight is maintained. In the event that satisfactory progress is not attained, physicians will assess the patient’s eligibility to either undergo pharmacotherapy or bariatric surgery. Physicians typically opt for bariatric treatment in the event that nonsurgical treatments have failed. It is important to note that best weight loss and maintenance results are achieved when pharmacotherapy or bariatric treatment is used in conjunction with lifestyle modifications.

Figure 14: A holistic approach to treating obesity.

References

1. Ng, M., Fleming, T., Robinson, M., Thomson, B., Graetz, N., & Margono, C. et al. (2014). Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.The Lancet, 384(9945), 766-781. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60460-8

2. Seidell, J. & Halberstadt, J. (2015). The Global Burden of Obesity and the Challenges of Prevention. Annals Of Nutrition And Metabolism, 66(2), 7-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000375143

3. WHO: Global Database on Body Mass Index. (2017). Apps.who.int. Retrieved 1 February 2017, from http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html

4. Child & Teen BMI | Healthy Weight | CDC. (2017). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 1 February 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html

5. Jitnarin, N., Poston, W., Haddock, C., Jahnke, S., & Tuley, B. (2012). Accuracy of body mass index-defined overweight in fire fighters. Occupational Medicine, 63(3), 227-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqs213

6. Spiegelman, B. & Flier, J. (2001). Obesity and the Regulation of Energy Balance. Cell, 104(4), 531-543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00240-9

7. Pietiläinen, K., Kaprio, J., Borg, P., Plasqui, G., Yki-Järvinen, H., & Kujala, U. et al. (2008). Physical Inactivity and Obesity: A Vicious Circle. Obesity, 16(2), 409-414. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.72

8. Cohen-Cole, E. & Fletcher, J. (2008). Is obesity contagious? Social networks vs environmental factors in the obesity epidemic. Journal Of Health Economics, 27(5), 1382-1387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.04.005

9. Masuo, K. (2000). A family history of obesity, a family history of hypertension and blood pressure levels. American Journal Of Hypertension, 13(6), S164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0895-7061(00)01125-0

10. Weaver, J. (2008). Classical Endocrine Diseases Causing Obesity. Obesity And Metabolism, 212-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000115367

11. Schwartz, T., Nihalani, N., Jindal, S., Virk, S., & Jones, N. (2004). Psychiatric medication-induced obesity: a review. Obesity Reviews, 5(2), 115-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789x.2004.00139.x

12. Dare, S., Mackay, D., & Pell, J. (2015). Relationship between Smoking and Obesity: A Cross-Sectional Study of 499,504 Middle-Aged Adults in the UK General Population. PLOS ONE, 10(4), e0123579. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123579

13. Vermeulen, A. (2005). The epidemic of obesity: Obesity and health of the aging male. The Aging Male, 8(1), 39-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13685530500049037

14. Schumann, N., Brinsden, H., & Lobstein, T. (2014). A review of national health policies and professional guidelines on maternal obesity and weight gain in pregnancy. Clinical Obesity, n/a-n/a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cob.12062

15. Why Is Sleep Important? - NHLBI, NIH. (2017). National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Retrieved 1 February 2017, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sdd/why

16. Gurevich-Panigrahi, T., Panigrahi, S., Wiechec, E., & Los, M. (2009). Obesity: pathophysiology and clinical management. Current Medical Chemistry, 16, 506-521. Retrieved from http://liu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:583167/FULLTEXT01.pdf

17. Odegaard, J., & Chawla, A. (2012). Adipose tissue metabolism in the obese. TheScientist. Retrieved 18 January 2017, from http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/33653/title/adipose-tissue-metabolism-in-the-obese/

18. Kahn, B. B., & Flier, J. S. (2000). Obesity and insulin resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 106(4), 473–481.

19. Després, J., & Marette, A. (1999). Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Insulin Resistance, 51-81. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-716-1_4

20. Klok, M. D., Jakobsdottir, S., & Drent, M. L. (2007). The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obesity Reviews, 8(1), 21-34. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789x.2006.00270.x

21. Kaszmi, A., Sattar.A., Hashim, R., Khan., S.P.., Younus, M., Khan, F.A. (2013). Serum Leptin values in the healthy obese and non-obese subjects of Rawalpindi. J Pak Med Assoc. 63(2), 245-8

22. Tschop, M., Weyer, C., Tataranni, P. A., Devanarayan, V., Ravussin, E., & Heiman, M. L. (2001). Circulating Ghrelin Levels Are Decreased in Human Obesity. Diabetes, 50(4), 707-709. doi:10.2337/diabetes.50.4.707

23. Walley, A.J., Blakemore, A.I.F. & Froguel, P. (2006). Genetics of obesity and the prediction of risk for health. Human Molecular Genetics. Retrieved 27January, 2017, from https://academic.oup.com/hmg/article/15/suppl_2/R124/626082/Genetics-of-obesity-and-the-prediction-of-risk-for

24. Rankinen, T., Zuberi, A., Chagnon, Y.C., Weisnagel, S.J., Argyropoulos, G., Walts, B., Perusse, L., & Bouchard, C. (2006). The human obesity gene map: the 2005 update. Obesity, 14(4), 529-644.

25. Pi-Sunyer, F. X., Becker, D. M., Bouchard, C., Carleton, R. A., Colditz, G. A., Dietz, W. H., … & Higgins, M. (1998). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 68(4), 899-917.

26. Lau, D. C., Douketis, J. D., Morrison, K. M., Hramiak, I. M., Sharma, A. M., Ur, E., & members of the Obesity Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Panel. (2007). 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 176(8), S1-S13.

27. Poirier, P., & Després, J. P. (2001). Exercise in weight management of obesity. Cardiology clinics,19(3),459-470.

28. Hey, H., Petersen, H. D., Andersen, T., & Quaade, F. (1987). Formula diet plus free additional food choice up to 1000 kcal (4.2 MJ) compared with an is energetic conventional diet in the treatment of obesity. A randomised clinical trial. Clinical Nutrition,6(3),195-199.

29. Lau, D. C., Douketis, J. D., Morrison, K. M., Hramiak, I. M., Sharma, A. M., Ur, E., & members of the Obesity Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Panel. (2007). 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 176(8), S1-S13.

30. Toubro, S., & Astrup, A. (1997). Randomised comparison of diets for maintaining obese subjects' weight after major weight loss: ad lib, low fat, high carbohydrate diet fixed energy intake. Bmj,314(707329.

31. 9 Popular Weight Loss Diets Reviewed by Science. (2016, October 04). Retrieved January 27, 2017, from https://authoritynutrition.com/9-weight-loss-diets-reviewed/

32. Poirier, P., & Després, J. P. (2001). Exercise in weight management of obesity. Cardiology clinics, 19(3), 459-470.

33. Tremblay, A., Nadeau, A., Despres, J. P., St-Jean, L., Theriault, G., & Bouchard, C. (1990). Long-term exercise training with constant energy intake. 2: Effect on glucose metabolism and resting energy expenditure. International journal of obesity, 14(1), 75-84.

34. Gwinup, G. (1987). Weight loss without dietary restriction: efficacy of different forms of aerobic exercise. The American journal of sports medicine, 15(3), 275-279.

35. Pate, R. R., Pratt, M., Blair, S. N., Haskell, W. L., Macera, C. A., Bouchard, C., … & Kriska, A. (1995). Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Jama, 273(5), 402-407.

36. Nozaki, T., Sawamoto, R., & Sudo, N. (2013). Cognitive behavioral therapy for obesity. Nihon rinsho. Japanese journal of clinical medicine, 71(2), 329-334.

37. Cooper, Z., Fairburn, C. G., & Hawker, D. M. (2003). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of obesity: A clinician's guide. Guilford Press.

38. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. (2002). The diabetes prevention program (DPP). Diabetes care, 25(12), 2165-2171.

39. Look AHEAD Research Group. (2003). Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Controlled clinical trials,24(5), 610-628.

40. Renjilian, D. A., Perri, M. G., Nezu, A. M., McKelvey, W. F., Shermer, R. L., & Anton, S. D. (2001). Individual versus group therapy for obesity: effects of matching participants to their treatment preferences. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 69(4), 717.

41. Wrotniak, B. H., Epstein, L. H., Paluch, R. A., & Roemmich, J. N. (2004). Parent weight change as a predictor of child weight change in family-based behavioral obesity treatment. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 158(4), 342-347.

42. Epstein, L. H., Roemmich, J. N., Stein, R. I., Paluch, R. A., & Kilanowski, C. K. (2005). The challenge of identifying behavioral alternatives to food: clinic and field studies. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30(3),201-209

43. Guerciolini, R. (1997). Mode of action of orlistat. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 21, S12-23.

44. Finer, N. (2002). Sibutramine: its mode of action and efficacy. International Journal of Obesity, 26(S4), S29.

45. Davidson, M. H., Hauptman, J., DiGirolamo, M., Foreyt, J. P., Halsted, C. H., Heber, D., … & Heymsfield, S. B. (1999). Weight control and risk factor reduction in obese subjects treated for 2 years with orlistat: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 281(3), 235-242.

46. James, W. P. T., Astrup, A., Finer, N., Hilsted, J., Kopelman, P., Rössner, S., … & STORM Study Group. (2000). Effect of sibutramine on weight maintenance after weight loss: a randomised trial. The Lancet, 356(9248), 2119-2125

47. Sjöström, L., Lindroos, A. K., Peltonen, M., Torgerson, J., Bouchard, C., Carlsson, B., … & Sullivan, M. (2004). Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(26), 2683-2693.