Table of Contents

Coronary Heart Disease

Introduction

Coronary heart disease or ischemic heart disease is a disorder characterized by the buildup of plaques in the coronary arteries thus leading to the narrowing of the arteries (NIH, 2016). The buildup of plaques is known as atherosclerosis. The plaques tend to accumulate throughout the years blocking circulation in the arteries. Common symptoms include angina or better known as chest pain or discomfort, pressure in arms and shoulders, neck, jaw, or back, a weakened heart, and is also a contributing factor to a heart attack (NIH, 2016). Over time, CHD can contribute to weakened heart muscle and tissue which can lead to heart failure and arrhythmias. However, lifestyle changes such as changing diet, working out and reducing stress, along with medications can reduce the risk of developing coronary heart disease (NIH, 2016). CHD contributes to ⅓ of deaths in people over 35 years old (Sanchis-Gomar et. al., 2016). It is also a major cause of death in developed regions mostly due to poor lifestyle habits and diets. Causes of this disease are often attributed to physical inactivity, nicotine abuse, and bac nutrition practices (Sanchis-Gomar et. al., 2016).

Epidemiology

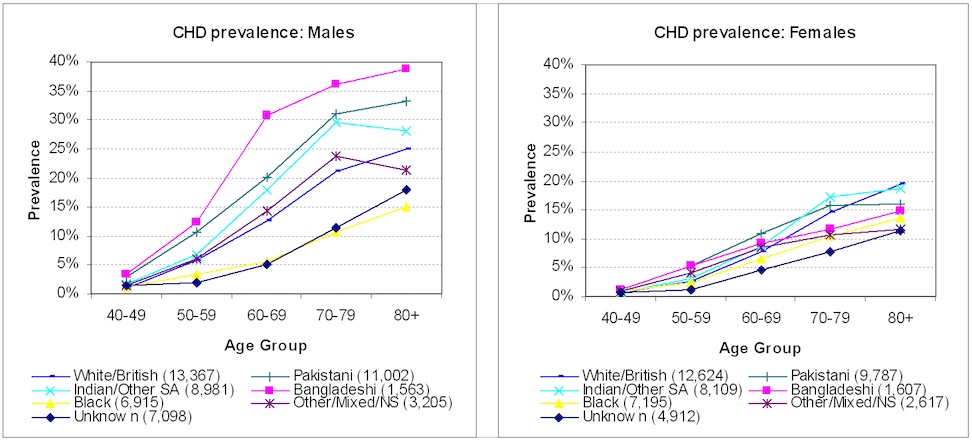

CHD incidence is on the rise worldwide and is a major cause of death in developed countries. It results in approximately one-third of deaths in individuals over the age of 35 years (Sanchis-Gomar et al., 2016). In 2016, the Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics reports that 15.5 milllion people in the USA over the age of 20 have been diagnosed with a manifestation of CHD. In the USA, approximately one-half of middle-aged men and one-third of middle-aged women develop CHD (Sanchis-Gomar et al., 2016). Despite increasing prevalence, age-standardized death rates have decreased by 22% since 1990 due to a shift in age demographics. The lifetime risk of developing CHD in individuals with more than 2 risk factors is 37.5% for men and 18.3% for women (Sanchis-Gomar et al., 2016). Estimates show that men over the age of 40 and women over the age of 45 are at most risk of CHD. Prevalence of CHD increases with age for both men and women (Sanchis-Gomar et al., 2016).

Figure 1: Outlining the Coronary Heart Disease prevalence in males and females, in differing age groups along with varying ethnicities to compare epidemiological results(Sanchis-Gomar et al., 2016).

Figure 1: Outlining the Coronary Heart Disease prevalence in males and females, in differing age groups along with varying ethnicities to compare epidemiological results(Sanchis-Gomar et al., 2016).

Risk Factors

The exact etiology of CHD is unknown but several genetic and environmental risk factors have been associated with an increased risk of developing CHD (Torpy et al., 2009).

Genetic (non-modifiable) risk factors (Torpy et al., 2009):

- Age - an increased incidence has been observed among individuals above the age of 40 years

- Sex - an increased incidence has been observed among males

- Family history - individuals with family members that have developed CHD are more at risk of developing it themselves

- Ethnicity - a higher prevalence has been observed among the non-white population

Environmental (modifiable) risk factors (Torpy et al., 2009):

- Smoking - an increased incidence has been observed among individuals who consume an abundance of tobacco

- High blood cholesterol levels - middle-aged individuals with high cholesterol levels show increased incidence of disease development

- Physical inactivity - individuals who do not exercise regularly are more at risk of developing CHD

- Stress - an increased incidence has been observed among individuals with above normal levels of cortisol and adrenaline that is released by stress

- Obesity - individuals with unhealthy diet and increased body fat are more at risk of developing CHD

Signs and Symptoms

Signs and symptoms for coronary heart disease (heart attack) are very similar to those who have angina, and can vary to the point where a repeated heart attack in the same patient may express different signs than the first one (NHLBI, 2015b). Also, not every heart attack begins as animated as it looks in mainstream media, with one-third of cases showing no chest pain at all (NHLBI, 2015b). Some of the most common symptoms include that of mild or severe chest pain, involving discomfort for a short (few minutes) period of time. This pain can be sharp, and feel very uncomfortable, similar to the pressure or compression felt of gastroesophageal reflux disease on the heart. There may also be some upper body discomfort, ranging from the arms to the back, shoulders, neck, jaw and/or upper pat of the stomach and below the breasts. In addition, shortness of breath can be a sign signalling discomfort to the heart, occurring either before or during the heart attack (NHLBI, 2015b). Other common symptoms include light-headedness, dizziness, nausea, vomiting, feeling unusually tired for no reason and breaking out in a cold sweat (NHLBI, 2015b).

Diagnosis

Electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG)

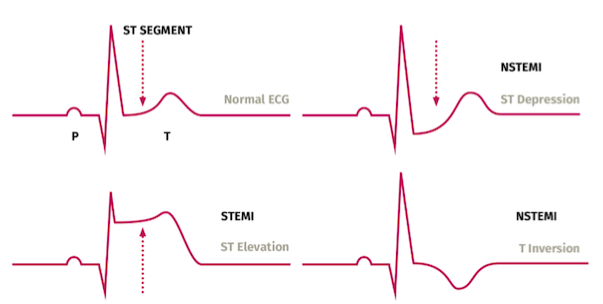

Normally, detection of coronary heart disease will result from a physician who has reviewed the patient’s medical and family history, as well as various test results (NHLBI, 2015). The first diagnostic test that is used is called an Electrocardiogram or ECG (EKG), and is also considered a non-invasive diagnostic tool as it is an external measurement of the heart (AHA, 2016). Essentially, a complete blockage of the coronary artery results in STEMI or ST-elevation myocardial infarction, also known as a transmural or epicardial injury (AHA, 2016; Klabunde, 2016). A partial blockage of the artery results in subendocardial ischemia, or ST-depression (Klabunde, 2016). Both of these patterns can be tracked through ECG, and indeed the ECG patterns can change as the coronary occlusion changes. Due to damage in the epicardial tissue, a myocardial infarction patient with ST-elevation will have ventricles that take an extended period of time to repolarize, thus allowing a positive ion influx and observation of an elevated ST portion of the ECG (Klabunde, 2016). In contrast, a patient with an injury in the subendocardial region, would have too little positive ion influx (greater depolarization) and cause the ST vector directed toward the inner ventricular region, thus exhibiting an ST-depression in the ECG (Klabunde, 2016).

Figure 2: Illustrates the observational pattern of the Electrocardiograph when the heart's electrical activity is modified. Top Left: Normal ECG Pattern, with baseline electrical levels. Top Right: Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction, when there is partial blockage of the artery, the heart will show an ECG pattern with ST-depression. Bottom Right: ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, when there is a complete blockage of the artery, the heart will show an ECG pattern of ST-Elevation. Bottom Right: ST-Depression with T Inversion(Klabunde, 2016).

Figure 2: Illustrates the observational pattern of the Electrocardiograph when the heart's electrical activity is modified. Top Left: Normal ECG Pattern, with baseline electrical levels. Top Right: Non-ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction, when there is partial blockage of the artery, the heart will show an ECG pattern with ST-depression. Bottom Right: ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction, when there is a complete blockage of the artery, the heart will show an ECG pattern of ST-Elevation. Bottom Right: ST-Depression with T Inversion(Klabunde, 2016).

Troponin Blood Test

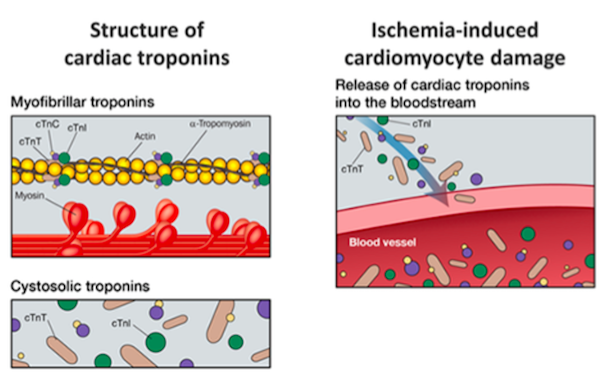

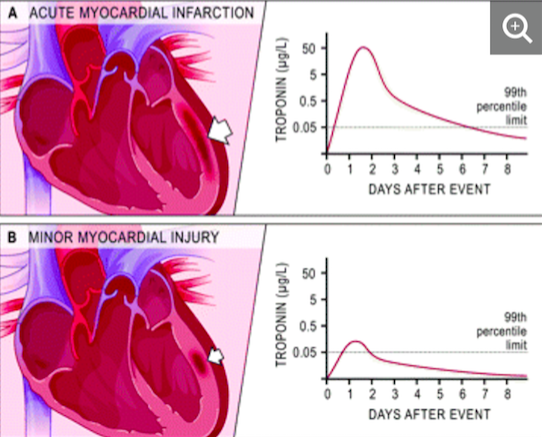

In addition to non-invasive tests, there are also invasive techniques such as troponin blood tests which detect cardiomyopathy (NHLBI, 2015a). This is a very versatile diagnostic which can uncover many cardiac syndromes, however research done by Melanson et al. in 2007 showed that for an acute myocardial infarction, troponin is an effective test in the clinical laboratory setting. For pre-requisite knowledge, troponin-T is normally bound to tropomyosin along actin filaments in cardiac muscle; they are regulatory proteins which control the calcium influx/outflow between actin and myosin (Sharma et al., 2004). The blood assay operates by making an antibody for cardiac troponin-T. This antibody then binds to any soluble troponin-T as a result of myocardial damage, thus allowing the physician to make a sensible diagnosis (Melanson et al., 2007). Research showed that for acute myocardial infarction, there is more than 50 ug/L of soluble troponin in the blood after 24-48 hours after the onset of chest pain (Melanson et al., 2007). In contrast, minor myocardial injury may only show approximately a maximum of 0.05 ug/L of soluble troponin (Melanson et al., 2007). As seen in the image, troponin-T levels decrease severals days post-injury.

Figure 3: Demonstrating Cardiac Troponin-T bound to actin filaments in cardiac muscle(Melanson et al., 2007).

Figure 3: Demonstrating Cardiac Troponin-T bound to actin filaments in cardiac muscle(Melanson et al., 2007).

Figure 4: Acute myocardial infarction illustrated by soluble Troponin-T levels as high as 50 ug/L. B: Minor myocardial infarction as seen with drastically lower levels of Troponin-T in the blood, with only over 0.05 ug/L after 24-48 hours(Melanson et al., 2007).

Figure 4: Acute myocardial infarction illustrated by soluble Troponin-T levels as high as 50 ug/L. B: Minor myocardial infarction as seen with drastically lower levels of Troponin-T in the blood, with only over 0.05 ug/L after 24-48 hours(Melanson et al., 2007).

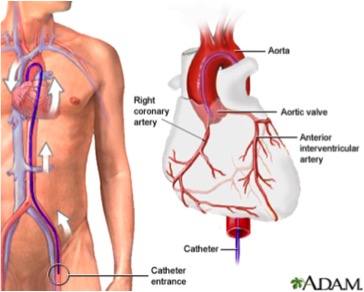

Cardiac Catheterization

Lastly, in addition to the blood test, another invasive procedure used to diagnose coronary heart disease is using coronary catheterization. Catheters operate by using a narrow, rubber-like hollow tube, in which a catheter is inserted in an attempt to diagnose and clear out an arterial occlusion (Robinson, 2011). The catheters are inserted through either the radial artery, brachial artery, or the most often used femoral artery, which provides ease of insertion and the least torturous path to the heart (Robinson, 2011). By using a special X-ray contrast dye, catheterization can display exactly where the occlusion is located, a process called cardiac angiography (AHA, 2017). In addition, catheterization can detect the pressure and oxygen content in the four chambers of the heart and also asses a small piece of heart tissue under a microscope (also called biopsy) (AHA, 2017).

Figure 5: Displaying cardiac catheterization beginning from a femoral artery entrance, making its way up the coronary artery to indicate the location of the plaque buildup, as well as take inter-arterial illustrations of the heart via a X-ray dye, thus conducting an angiogram(Robinson, 2011).

Figure 5: Displaying cardiac catheterization beginning from a femoral artery entrance, making its way up the coronary artery to indicate the location of the plaque buildup, as well as take inter-arterial illustrations of the heart via a X-ray dye, thus conducting an angiogram(Robinson, 2011).

Pathophysiology

Atherosclerosis: Atherosclerosis is the buildup of plaques in the arteries restricting the flow of oxygen-rich blood from moving inside the heart and body (Gibbons, 2013). The plaque is made up of fat, cholesterol, calcium, and other components and continues to grow larger in the arteries (Gibbons, 2013). As people age, the plaque narrows the arteries and hardens making it difficult for oxygenated blood to enter the heart and body (Gibbons, 2013). This can result in a heart attack or cardiac arrhythmia (Gibbons, 2013). Atherosclerosis can happen in any arteries in the body but can be attributed to CHD in the coronary arteries. This is what is responsible for angina or chest pain that is often contributed to CHD.

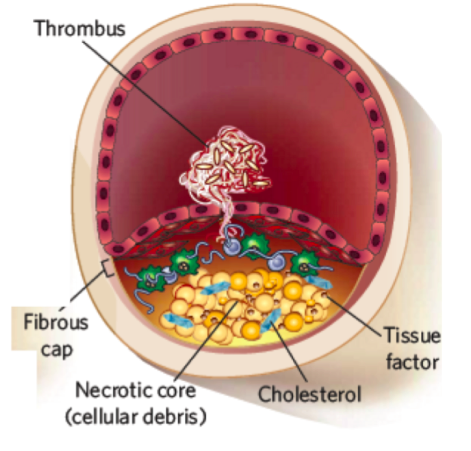

Lesion formation: Arterial inflammation has been considered a contributing factor to CHD and atherosclerosis (Libby and Theroux, 2011). Immune response and effector molecules contribute to the formation of lesions which arise from inflammation of the arterial walls. This inflammation results in atherosclerosis which is the main symptom of CHD (Hansson, 2005). Atherosclerotic lesions look like asymmetrical focal thickenings of the innermost layer of the artery and are made up of cells, connective tissue, and Lipids (Hansson, 2005). Inflammatory and immune cells along with vascular endothelial and smooth cells all contribute to the formation of fatty streaks, which is an accumulation of lipid-laden cells underneath the endothelium (Hansson, 2005). Fatty streaks are made up of macrophages and T cells (Hansson, 2005). These immune cells can signal a cytotoxic storm, recruiting inflammatory cytokines which are attributed to the inflammation that can occur (Hansson, 2005). The activation of plaques and inflammation contributes to cardiac ischemia and infarctions. Moreover, lesions can result in plaque rupturing and endothelial erosion (Hansson, 2005). If the plaque ruptures, many thrombotic materials can be exposed to the blood which can trigger acute coronary syndrome (Hansson, 2005).

Thrombosis: Foam cells die, and this results in the release of cellular debris and crystalline cholesterol as seen in the figure below (Rader and Daugherty, 2008). The smooth muscles form a fibrous cap beneath the endothelium layer which isolates the plaque (Rader and Daugherty, 2008). This contributes to the formation of a necrotic core within the plaque, and recruiment of more inflammatory cells (Rader and Daugherty, 2008). The plaque can eventually rupture or the endothelium can erode, which results in the exposure of the thrombogenic material and formation of thrombus in the lumen (Rader and Daugherty, 2008.

Figure 6: Demonstrates the last stage of progression of atherosclerosis in which there is thrombus formation (Radar and Daugherty, 2008).

Figure 6: Demonstrates the last stage of progression of atherosclerosis in which there is thrombus formation (Radar and Daugherty, 2008).

Treatment

Lifestyle

Lifestyle changes is important to prevent coronary artery disease. A heart-healthy lifestyle can help to reduce risk factors of coronary artery disease such as high cholesterol, and high blood pressure.

Healthy Eating: A heart-healthy diet includes fat-free dairy products, fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and fish high in omega-3 fatty acids (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016). The two main nutrients that can increase blood cholesterol include saturated fats, and trans fat. In a healthy diet, only 5 percent to 6 percent of the daily calories should come from saturated (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016). When following a heart-healthy diet, it is important to avoid eating red meat, sugary foods and beverages, and palm and coconut oils because these food products have high amounts of both saturated and trans fat (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016). The diet should include more consumption of monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats, as these fats help to lower blood cholesterol levels. Examples of these fats include avocados, salmon, trout, nuts and seeds, and tofu (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016).

Physical Activity: Physical activity can help to control coronary artery disease risk factors such as LDL cholesterol, high blood pressure, and help to maintain a healthy weight (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016). Physical activity lowers blood pressure, and triglycerides found in the blood, and raise HDL cholesterol levels. Physical activity is an effective way to overall improve and boost heart health, which can improve symptoms and reduce mortality in patients with coronary artery disease (Jolliffe et al., 2001). According to a study conducted in 2001, it was concluded that physical activity reduces total mortality of patients with coronary artery disease by 25 to 30 percent (Jolliffe et al., 2001).

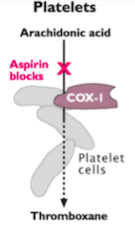

Aspirin

Antiplatelet medicines prevent blood clots from forming in arteries, and can thereby prevent heart attack or stroke (Frishman et al., 2005). An example of an antiplatelet medication is aspirin. Aspirin prevents the conversion of arachidonic acid to proaggregatory molecule known as thromboxane (Frishman et al., 2005). Thromboxane is a vasoconstrictor, and a hypertensive agent, which facilitates platelet aggregation as it stimulates the activation of new platelets (Frishman et al., 2005). Aspirin inhibits cyclooxygenase (COX-1) in platelets and prevents platelet aggregation, and thus reduces clotting. Aspirin is an anti-prostaglandin which leads to reduced inflammation in blood vessels as well (Frishman et al., 2005).

Figure 7: Shows the mechanism of action of aspirin as an anti-platelet drug (Frishman et al., 2005).

Figure 7: Shows the mechanism of action of aspirin as an anti-platelet drug (Frishman et al., 2005).

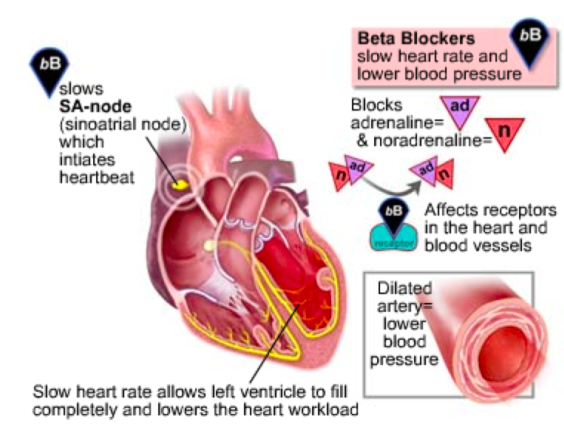

Beta-Blockers

Beta-blockers is a medication that is used to control abnormal heart rhythms, and treat high blood pressure (Frishman et al., 2005). Beta-blockers are antagonists that block the beta-adrenergic receptors for epinephrine and norepinephrine that mediates a flight or fight response (Frishman et al., 2005). The beta receptors are found on cells of the heart muscles, smooth muscles, arteries, kidneys, and other tissues that are part of the sympathetic nervous system. The flight or fight response accelerates heart-rate and causes vasoconstriction increasing blood pressure as a result of stimulation of the beta-receptors by epinephrine and norepinephrine (Frishman et al., 2005). However, exogenously administered beta-blockers bind preferentially and reversibly to the beta-receptor and competitively inhibits the epinephrine and norepinephrine, and weakens the effect. This results in slowing the heart rate, decreasing cardiac output, lessens the force with which heart muscle contracts, and dilates blood vessels. Examples of beta blockers include atenolol, metoprolol, nebivolol, and bisoprolol (Frishman et al., 2005).

Figure 8: Demonstrates beta-blockers as an antagonist, and its effects by lowering heart workload in a patient with coronary heart disease (Frishman et al., 2005).

Figure 8: Demonstrates beta-blockers as an antagonist, and its effects by lowering heart workload in a patient with coronary heart disease (Frishman et al., 2005).

Nitroglycerin

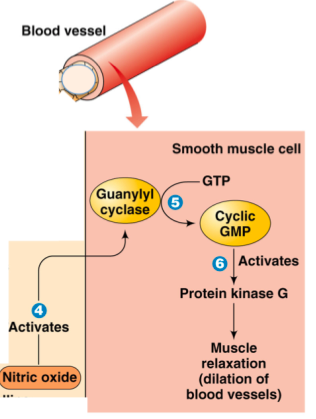

Nitroglycerin is a medication used for high blood pressure. It is administered by mouth, under the tongue, applied to the skin, or by injection into a vein (Kukovetz et al., 1987). Nitroglycerin mode of action is not entirely clear, but it is an effective treatment that functions to dilate blood vessels as it is a precursor to nitric oxide, a potent vasodilator (Kukovetz et al., 1987). Nitroglycerin is converted to nitric oxide in the body my the enzyme mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. Once it is converted to nitric oxide in the blood, it activates guanylyl cyclase, which results in the formation of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) from guanosine triphosphate (GTP) (Kukovetz et al., 1987). This activates protein kinase G, which stimulates dephosphorylation of myosin, and results in muscle relaxation and dilation of blood vessels (Kukovetz et al., 1987).

Figure 9: Illustrates nitroglycerin as a precursor for nitric oxide, and its direct activation of pathways to allow vasodilation(Kukovetz et al., 1987).

Figure 9: Illustrates nitroglycerin as a precursor for nitric oxide, and its direct activation of pathways to allow vasodilation(Kukovetz et al., 1987).

Angioplasty

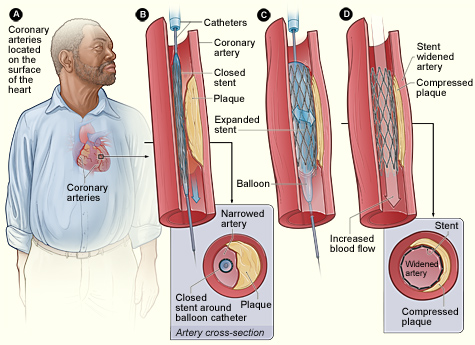

Coronary Angioplasty, also known as PCI is a nonsurgical procedure that improves the overall blood flow to the heart by cardiac catheterization. It requires the insertion of a catheter tube, and injection of contrast dye that is iodine based into coronary arteries (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016). This medicinal procedure is followed to open coronary arteries that are narrowed or blocked by the buildup of artherosclerotic plaque. The doctor will numb an area on the wrist or groin, and a small hole will be made to insert the catheter into the blood vessel (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016). The doctor uses live x-rays to guide the catheter to the heart to inject special contrast dye that will show the blockage. Another catheter is used over a guidewire, and a balloon is inflated at the tip of that catheter (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016). A small mest tube called a stent is placed in the artery to keep the artery open. After the procedure, the doctor will remove the catheter and close and bandage the opening on the wrist or groin (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016). If a stent is implanted, anticlotting medicines are prescribed for three to 12 months. Complications can arise from this procedure, which may include bleeding, blood vessel damage, and allergic reaction to the dye. The risk of complications is higher if the patient is older, and has extensive heart disease or multiple blockages in the coronary arteries (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016).

Figure 10: Illustrates a step-by-step procedure of angioplasty, which is a medicinal procedure for coronary artery disease (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016).

Figure 10: Illustrates a step-by-step procedure of angioplasty, which is a medicinal procedure for coronary artery disease (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2016).

Future Therapeutics

PCSK9-specific siRNA

Recently, highly effective treatments have been approved for individuals who are at elevated risks without cardiovascular disease (CDK) – primary prevention, and for those who are experiencing the early stages of the disease – secondary prevention (Hobbs, 2004). Such therapeutics deviate from the conventional statins for their mechanisms in lowering plasma cholesterol levels. The purpose in the development of alternative lipid-lowering medications due to the associated side effects of statin drugs such as muscle pain, liver damage, and development of diabetes (Golomb, 2008). Additionally, studies have shown that 1 in 5 individuals medicated on statin will experience insufficient decrease in cholesterol levels (Ziaeian, 2017). Therefore, further therapeutics have been developed to either supplement with the conventional statin therapy, or to be provided independently. One example is the PCSK9 inhibitors, which are monoclonal antibodies that targets and inactivates a protein liver known as proprotein convertase subtilsin kexin 9 (PCSK9) (Chaudhary, 2017). To elaborate, LDL receptors (LDLR) expressed on hepatocytes binds and initiates the intracellular ingestion of LDL-particles from the extracellular fluid (Wieinreich et al., 2014). PCSK9 functions by binding to LDLRs, which leads to degradation and the inability to be recycled back to the hepatocyte membrane. Therefore, by inhibiting PCSK9, more LDLRs are recycled and presented on the cell surface, which leads to the reduction in circulating LDL cholesterol concentrations in plasma (Weinreich et al., 2014). Although this therapy has been approved by the FDA in 2015 for its safety and efficacy; such inhibitors are given by injection every 2-4 weeks (Cariou, 2013). Hence, further research has been conducted to discover alterative novel methods in lowering PCSK9 levels for prolonged durations – without the need to perform biweekly injections. Currently, small interfering RNA (siRNA) has been investigated as an alternative method CDK treatment, as it has been associated with prolonged reductions in LDL cholesterol levels for over several months (Tang, 2007; Ray, 2017) SiRNA’s can direct-specific degradation messenger RNA for PCSK9, leading to suppression of PCSK9 protein synthesis. This PCSK9-specific siRNA is encapsulated in a lipid nanoparticle and delivered by a single injection every 6-12 months (Zatsepin, 2016). Although this alternative method in lowering LDL plasma levels by utilizing PCSK9 mechanism shows promise; there has been concern due to its associated effects of hepatotoxicity. Therefore, ongoing studies are currently conducted to determine the safety and efficacy (Frank-Kamenetsky, 2008).

Anti-inflammatory Therapies The mechanisms behind the rupturing or erosion of the fibrous cap leading to unstable coronary atheromatous plaques have yet been elucidate. However, it can been believed that local or systemic inflammation can be an underlying etiology for such processes (Libby, 2002). Studies have evidently shown that chronic low-level system inflammation has been associated with greater risk for CDK (Minihane, 2015). In addition, further studies have shown benefits, and a reduction of cardiovascular risk in CDK patients from anti-inflammatory therapeutics (Charo, 2014). These agents include colchicine, canakinumab, and methotrexate, which are currently in trials to assess its efficacy in reducing cardiovascular risks, and whether it plays a role in destabilizing atheroma plaques (Ridker, 2014).

Personalized Antithrombotic Therapies Atherothrombosis known as atherosclerotic plaque disruption with superimposed thrombosis is clinically manifested in coronary heart disease (Viles-gonzalez, 2004). In order to treat patients at risk for atherotrombosis, anti-thrombotic therapy can be provided to prevent ischemic events, however, it is often associated with an increased risk of bleeding (Fitzmaurice, 2002). Currently, low-dose aspirin has been used for long-term prevention as anti-coagulation therapy. Though, future methods may consider combinational antiplatelet, anticoagulants, along with the assessment of intensity, and duration of therapy to achieve optimal benefits for each patient (Eikeboom, 2007).

Conclusion

To conclude, Coronary heart disease is a disorder characterized by atherosclerosis, which tend to accumulate and may potentially block the circulation of arteries. Although current treatments are such as aspirin, beta-blockers, nitroglycerin, and angioplasty are effective treatments; future therapeutics are underway to create alternative options for individuals who may show minor beneficial outcomes to current treatments, or to further improve the state of the disease. With over 7 million deaths/ annually, it is hoped that such novel treatments will diminish the number of those who are affected (WHO, 2015).

References

AHA. (2017). Cardiac catheterization. Retrieved December 01, 2017, from http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartAttack/SymptomsDiagnosisofHeartAttack/Cardiac-Catheterization_UCM_451486_Article.jsp#

AHA. (2016). Diagnosing a heart attack. Retrieved December 01, 2017, from http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/HeartAttack/DiagnosingaHeartAttack/Diagnosing-a-Heart-Attack_UCM_002041_Article.jsp#.WiEBqLSnG1t

Cariou, B., Langhi, C., Le Bras, M., Bortolotti, M., Lê, K.-A., Theytaz, F., … Costet, P. (2013). Plasma PCSK9 concentrations during an oral fat load and after short term high-fat, high-fat high-protein and high-fructose diets. Nutrition & Metabolism, 10(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.1186/1743-7075-10-4

Charo, I. F., & Taub, R. (2011, May). Anti-inflammatory therapeutics for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Nature Reviews Drug Discovery. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd3444

Chaudhary, R., Garg, J., Shah, N., & Sumner, A. (2017). PCSK9 inhibitors: A new era of lipid lowering therapy. World Journal of Cardiology, 9(2), 76. https://doi.org/10.4330/wjc.v9.i2.76

Eikelboom, J., & Hirsh, J. (2007). Combined antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy: clinical benefits and risks. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 5, 255–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02499.x

Fitzmaurice, D. a, Blann, A. D., & Lip, G. Y. H. (2002). Bleeding risks of antithrombotic therapy. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 325(7368), 828–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7368.828

Frank-Kamenetsky, M., Grefhorst, A., Anderson, N. N., Racie, T. S., Bramlage, B., Akinc, A., … Fitzgerald, K. (2008). Therapeutic RNAi targeting PCSK9 acutely lowers plasma cholesterol in rodents and LDL cholesterol in nonhuman primates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(33), 11915–11920. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0805434105

Frishman, W. H., Cheng-Lai, A., & Nawarskas, J. (Eds.). (2005). Current cardiovascular drugs. Springer Science & Business Media.

Golomb, B. A., & Evans, M. A. (2008). Statin adverse effects : a review of the literature and evidence for a mitochondrial mechanism. American Journal of Cardiovascular Drugs : Drugs, Devices, and Other Interventions, 8(6), 373–418. https://doi.org/10.2165/0129784-200808060-00004

Jolliffe, J. A., Rees, K., Taylor, R. S., Thompson, D., Oldridge, N., & Ebrahim, S. (2001). Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 1(1).

Klabunde, R. E. (2016). Electrophysiological changes during cardiac ischemia. Retrieved December 01, 2017 from http://www.cvphysiology.com/CAD/CAD012

Kukovetz, W. R., Holzmann, S., & Romanin, C. (1987). Mechanism of vasodilation by nitrates: role of cyclic GMP. Cardiology, 74(Suppl. 1), 12-19.

Libby, P., Ridker, P. M., & Maseri, A. (2002). Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Inflammation and Atherosclerosis, 105, 1135–1143. https://doi.org/10.1161/hc0902.104353

Libby, P., & Theroux, P. (2005). Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation, 111(25), 3481-3488

Melanson, S. E. F, Tanasijevic, M. J., Jarolim, P. (2007). Cardiac troponin assays: a view from the clinical chemistry laboratory. Circulation, 116, 8. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.722975

Minihane, A. M., Vinoy, S., Russell, W. R., Baka, A., Roche, H. M., Tuohy, K. M., … Calder, P. C. (2015). Low-grade inflammation, diet composition and health: current research evidence and its translation. The British Journal of Nutrition, 114(7), 999–1012. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114515002093

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.(2016). How is Coronary Heart Disease Treated ?. Retrieved November 26, 2017, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/cad

NHLBI. (2015a). How is a heart attack diagnosed? Retrieved December 01, 2017, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/heartattack/diagnosis

NHLBI. (2015b). What are the symptoms of a heart attack? Retrieved December 01, 2017, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/heartattack/signs

R., H. (2004). Cardiovascular disease: Different strategies for primary and secondary prevention? Heart, 90(10), 1217–1223. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2003.027680

Rader, D. J., & Daugherty, A. (2008). Translating molecular discoveries into new therapies for atherosclerosis. Nature, 451(7181), 904-913.

Ray KK Leiter LA Dufour R, Karakas M, Hall T, Troquay RP, Turner T, Visseren FL, Wijngaard P, Wright RS, Kastelein JJ, Landmesser U, K. D. (2017). Inclisiran in Patients at High Cardiovascular Risk with Elevated LDL Cholesterol. New England Journal of Medicine. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=cctr&NEWS=N&AN=CN-01368245

Ridker, P. M., Lüscher, T. F., Libby, P., Ridker, P., Hansson, G., Swirski, F., … Couzin-Frankel, J. (2014). Anti-inflammatory therapies for cardiovascular disease. European Heart Journal, 35(27), 1782–91. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehu203

Robinson, S. A. [Robinson Visual Science]. (2012, April 3). Cardiac catheterization via femoral artery. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aMjZRx1ILhc

Sharma, S., Jackson, P. G., & Makan, J. (2004). Cardiac troponins. Journal of Clinical Pathology, 57(10), 1025–1026. http://doi.org/10.1136/jcp.2003.015420

Tang, Y., Ge, Y. Z., & Yin, J. Q. (2007, January). Exploring in vitro roles of siRNA in cardiovascular disease. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7254.2006.00491.x

Viles-Gonzalez, J. F., Fuster, V., & Badimon, J. J. (2004, July). Atherothrombosis: A widespread disease with unpredictable and life-threatening consequences. European Heart Journal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehj.2004.03.011

Weinreich, M., & Frishman, W. H. (2014). Antihyperlipidemic therapies targeting PCSK9. Cardiology in Review, 22(3), 140–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/CRD.0000000000000014

World Health Organization. (2015). WHO | Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) factsheet No. 317. https://doi.org/Fact sheet N°317

Zatsepin, T. S., Kotelevtsev, Y. V., & Koteliansky, V. (2016, July 5). Lipid nanoparticles for targeted siRNA delivery - Going from bench to bedside. International Journal of Nanomedicine. Dove Medical Press Ltd. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJN.S106625

Ziaeian, B., & GC, F. (2017). Statins and the prevention of heart disease. JAMA Cardiology. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2016.4320