This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Obesity Powerpoint

Obesity

Obesity is a common and preventable disease that is characterized by abnormal or excessive fat accumulation in adipose tissue.[1] The excess accumulation of fat leads to the impairment of health and is subsequently a major risk factor for the development of various non-communicable diseases such as diabetes, as well as premature death.[2]

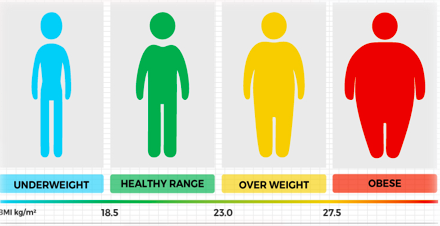

Body Mass Index & Limitations

There are various methods which can be used to measure excessive adipose tissue in the body.[3] This includes skinfold thickness measurements, underwater weighing and bioelectrical impedance. The drawbacks of these methods is that they are not always readily available, the are either expensive or require highly trained personal to be conducted. In addition, many of these methods can be difficult to standardize, making it difficult for comparisons across studies and time periods.[3] Anthropometric measurements such as weight and height are the most basic methods of assessing body composition.[4] Specifically, body weight is the most frequently used measure of obesity.[4] Body mass index (BMI) is a metric that is used to assess body weight.[3] It is measured by dividing an individuals weight in kilograms by their height in meters squared. BMI is widely used as a risk factor for the development and prevalence of disease.[3]

The advantages of BMI are that it is useful for measuring obesity in a population.[4] It is a general measure of obesity that can be used for most individuals.[3] In addition, changes in BMI levels allow researchers to get a good idea of changes of obesity levels in a population.[3] Despite its strengths, BMI has many limitations when used to assess body weight.[4] For instance, it does not differentiate between lean and fat body mass. An individual may have a healthy weight according to their BMI, but still face health risks due to excessive body fat. Another limitation of BMI is that it overestimates health risks for individuals with increased muscle mass.[4]

Epidemiology

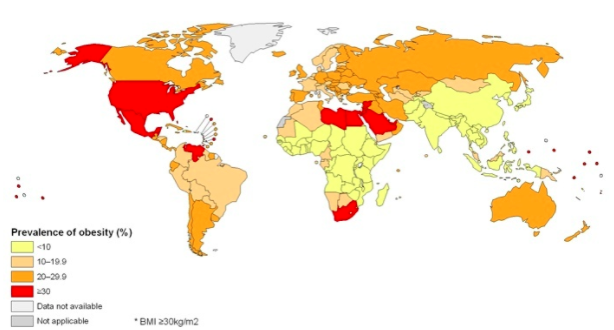

World Wide Prevalence

Undoubtedly, obesity is a disease that continues to sweep the globe. Over the past 3 and a half decades alone, the obesity prevalence has nearly doubled.5 In 2016, 650 million adults and 340 million children qualified as obese. Additionally, amongst children, 41 million under the age of 5 were considered overweight or obese.6 This constitutes a worldwide count of 990 million obese individuals. From a statistical point of view, nearly 30% of the world’s population are overweight or obese.7 Obesity tends to be more prevalent in women than in men, with 14% of women worldwide and 10% of men worldwide affected by the disease.8,9

Ethnic Prevalence

Majority of the world’s population live in countries where obesity and/or being overweight kills more people than from being underweight.6 Obesity rates are greater in certain ethnic subpopulations. The rates range from lower than 6% in Korea and Japan to greater than 30% in the United States, Mexico, New Zealand, and Hungary. Canada, Australia, United Kingdom, Chile, and South Africa are a close second, with greater than 25% of adults categorized as obese in each of these countries. In Canada, the United States, Mexico, England, France, and Switzerland, obesity rates have been on a steady incline since the 1990s. It is believed that some countries have had stabilized prevalence of obesity, however, there is no definitive indication of reduction of the epidemic anywhere.10

Canadian prevalence

In Canada, an estimated 14 million adults and 470,000 youth are characterized as obese.11 Approximately 25% of Canadians are obese. Two provinces, British Columbia and Quebec, have the lowest levels of obesity. The greatest prevalence is observed in the Northwest Territories and Newfoundland and Labrador. City-wise, the lowest levels of obesity are seen in Canada’s three largest cities: Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver.12

Ontario (local) prevalence

Ontario has been reported to have a province-wide obesity prevalence of about 25%, which is the same as the national average. However, some Ontario cities ranked in the higher end, with Sudbury, Brantford, Hamilton, and Thunder Bay being the second, fourth, fifth and seventh most obese cities, respectively, in the country.12

Evolutionary Basis of Obesity

Human babies and the need for fat

Human babies have the highest percent fat at birth for mammals.13 They have 15% body fat at birth. The second highest mammal for body fat % is the guinea pig, with 10.8. Adipose tissue is used as insulation to prevent heat from escaping the body. Human beings are hairless mammals, and therefore, are exposed to environmental stressors more directly then say a polar bear. The fur a polar bear has allows it to survive at temperatures as low as -69 degrees Celsius, even though they have a lower fat percentage than humans. Another reason humans require a high fat percentage at birth is because of the size of their brains. It is estimated that the infant brain consumes 50-60% of its total metabolic expenditure.14 The brain is not only an expensive organ, but it is also a sensitive one. It requires lots of fat to maintain itself and grow, as well as insulation to keep it at a steady temperature of around 38 degrees Celsius. This explains our natural tendency to store fat more effectively than other mammals.

An important question remains: If obesity is such a detrimental condition to the human population, then why is it so evident today?

Theory One

Evolutionarily speaking, the ability to store fat is quite the effective adaptation. Food supplies could be abundant one day, and depleted the next. This is why it is believed that another major reason for fat storage in humans is in fact an energy reserve.15 Although obesity is quite the pandemic in many developed nations today, it was rare throughout our evolutionary history within primitive populations. In fact, there is evidence to suggest no obesity within traditional hunting and gathering populations.15 Regardless, those with genes that promoted greater storage of fat had a higher likelihood to survive when resources became scarce. This has led to evolutionary pressures to select for genes doing just that. In the next section concerning gender and obesity, this is elaborated in more detail.

Theory Two

Obesity was often perceived as a status of wealth and power.15 This is because only those who had access to high energy foods on a year round basis were able to actually become overweight. This would have lead it to be a desirable trait of the opposite sex over evolutionary time.

Obesity and Gender

Obesity is seen primarily in females versus males.16 Figure 1 shows the distribution of obesity by gender for differential income as well as geographic location. It is clear that regardless of social status or ethnic location the overwhelming majority of obese and overweight individuals are in fact female.In fact, 15% body fat is average for males and 25% is average for females.16 This is the case for several reasons. Firstly, woman (evolutionarily speaking) were not required to engage in as many physically demanding activities as males were. Males, having to hunt, build etc were exposed to greater stressors on their bodies compared to their female counterparts.15 This lead to a higher percentage of muscle mass, and a lower percentage of fat for males. The second (and perhaps more pressing reason) is the fact that females are tasked with giving birth. Child bearing is very costly to a mother, and requires a large amount of energy to facilitate a very fragile fetus. Further, following childbirth breast milk is excreted that is full of nutrients and fat. This high fat milk is crucial to the development of a healthy child.17

* add graph with gender and bar graphs

Pathophysiology

Macronutrients Vs Micronutrients

Macronutrients Vs Micronutrients Macronutrients are the energy providing nutrients and are thus needed in larger amounts. These include carbohydrates, proteins and fats.18 Carbohydrates are they body’s main energy source, whereas proteins provide the amino acids important for the cell structure and the cell membrane.18 On the other hand, fats are used for making steroid and hormones in the body.18 Furthermore, fats have the highest caloric content with approximately 9 calories per gram of fat, and when burned, they provide the largest amount of energy compared to carbohydrates and proteins.18 It has been reported that a high-fat diet induces the development of obesity.19 There is a direct correlation between the amount of dietary fat and overconsumption, thus leading to weight gain.19 It is speculated that this may be due to dietary fat’s weak satiety properties, leading to the feeling of not being satisfied or full after a meal.19

Micronutrients on the other hand are needed in smaller quantities and are essential for various chemical reactions in the body.18 These include vitamins and minerals.18 Vitamins allow for normal growth and metabolism as well as cellular functions.18 These may be fat-soluble vitamins which are stored in the fatty tissues such as Vitamins A, D, E and K.18 They may also be water-soluble which are excreted in the urine and must be taken daily such as Vitamins B and C.18 Minerals are ionized in the body, for instance iron, sodium and potassium.18

Types of Adipocytes

Body fat or adipose tissue is composed of loose connective tissue which mostly consists of adipocytes or fat cells (6). White adipose tissue (WAT) and brown adipose tissue (BAT) are the two types of adipocytes which make up the majority of adipose tissue (6). Beige adipocytes are a third type of adipocyte, which have recently been identified, however their function and origin is not well understood (7).

White adipocytes are the main cell type found in human adipose tissue (6). Their main function is to store energy and they provide most of the total body fat. WAT cells have receptors for insulin, sex hormones, norepinephrine and glucocorticoids (6). They secrete proteins such as leptin, adiponectin as well as other adipokines (7). Furthermore, WAT is involved in controlling metabolism by acting as a thermal insulator to help maintain energy homeostasis (7).

Brown adipocytes are found in almost in all mammals and they function to dissipate energy through thermogenesis (8). Their characteristic brown appearance is due to a high number of iron-containing mitochondria (8). BAT develop from the middle embryonic layer, the mesoderm, which is also the source of muscle cells and adipocytes (6). It is abundant in newborns as well as metabolically active adult humans, however, its prevalence decreases in humans as they age (6). Furthermore, brown adipocytes also contain more capillaries than white fat, which allows for tissue to be supplied with more oxygen and nutrients (8). In this way, produced heat can easily be distributed throughout the body (8).

insert adipose figure 4 image

Normal Function of Adipose Tissue & Adipose Tissue Development

Adipose tissue is an endocrine organ which is mainly responsible for energy storage as well as the synthesis and secretion of several hormones (9)20. Adipose tissue is a major source of free fatty acids. Free fatty acids (FFA) are liberated from lipoproteins by lipoprotein lipase, allowing it to enter the adipocyte where it is reassembled into triglycerides by esterifying it onto glycerol. Adipocytes have an important physiological role in maintaining triglyceride and FFA levels (9)20.

In conditions of obesity, hyperplasia and hypertrophy lead to the expansion of adipose tissue, which results in the development of adipocytes that are metabolically unhealthy (10).21 The activation of biological pathways that favour the differentiation of adipocytes as well as the formation of adipocytes from precursor cells produces an increase in the number of adipocytes (10). There are certain proteins and transcriptional factors involved in inhibiting or promoting the development of adipocytes (9). Adipogenesis, the development of adipose tissue, involves the differentiation of preadipocytes into mature fat cells. Changes in transcription factor expression and activity is what results in the differentiation of these pre-adipocytes into mature fat cells.Transcription factors involved in promoting adipogenesis include the AP-1 family, PPARy, STATs, members of the KLF family, SREBP-1 and members C/EBP family. Conversely, Pref-1, GATA and Wnt family transcription factors are involved in inhibiting adipogenesis (9).

Pre-adipocytes within adipose tissue can differentiate into mature adipocytes throughout their lifetime (10).This allows for the expansion of adipose tissue when increased storage requirements are needed. Furthermore, mature adipocytes have the ability to accommodate increased storage needs, and in cases of overnutrition, these cells can become hypertrophic (10).

Adipose tissue undergoes a continuous process of remodelling(11). This normally maintains tissue health, however, this process is accelerated in obesity which can lead to the death of adipocytes along with the recruitment and activation of immune cells. Increased activation of the immune system leads to inflammation, which is the hallmark of obesity. Overall, an increase in the death of adipocytes, coupled with an increase in immune cell activation leads to many of the pathophysiological consequences of obesity (11).

Hormones

Endorphin release when you eat

When energy-dense or high calorie food is consumed, endorphins and enkephalins are released in the brain, which are the brain’s natural opioids. Consuming fats and sugars essentially triggers shifts in the brain that are associated with addictive drugs such as heroin. This then stimulates dopamine release into the nucleus accumbens in the midbrain. Subsequently, this creates a feeling of reward.1 Fast food meals can be extremely high in calories and can contain almost all of the recommended caloric daily intake for a person in a single sitting. This can cause physiological changes which may mute or alter the hormones responsible for satiety.1

Leptin

Leptin is produced and secreted by adipose tissue in the body.2 To signal satiety, the fat cells release leptin into the bloodstream, which then provides a signal in the hypothalamus, promoting a feeling of fullness.3 When leptin levels fall in response to lack of food or fasting, a signal is sent back to the body by the brain to promote food intake and a decrease in energy expenditure.3 Because leptin is produced in fat cells, leptin levels are higher in obese people. However, people who are obese are not as sensitive to leptin and are thought to have a resistance to the hormone.2

Insulin

Insulin is a hormone produced by the beta-cells of the pancreas.2,4 It plays a large role in the metabolism of carbohydrates and fat. Insulin maintains energy levels and ensures the body has the available energy it requires. It does this by stimulating glucose uptake in the blood from surrounding tissues.2 When the body has the energy it needs, there is no need to consume more energy through food. In obesity, insulin signals are lost or become insensitive, therefore glucose uptake is low, and appetite suppression does not occur since there is not adequate signalling indicating the body has enough energy.4 This can lead to the development of type II diabetes.2 These defects may occur due to impaired insulin signalling in fat and muscle tissue, and a downregulation of the major insulin-responsive glucose receptor in fat cells, GLUT4.4

Sex Hormones

Estrogens, the female sex hormones, and androgens, the male sex hormones, play a role in regulation of body fat distribution.2 As women age and become postmenopausal, they produce lower levels of estrogen in their ovaries. Most of their estrogen is actually produced in their body fat, however this is not nearly the same amount that is produced by premenopausal ovaries. This plays a role in accumulation of fat around the abdomen, and animal studies have exhibited excessive weight gain associated with lack of estrogen.2 As men age, the level of androgens produced by the testes also decreases.2 Low levels of androgens have been associated with abdominal fat and obesity as well.5

Ghrelin

Ghrelin is a fast-acting hormone that plays a role in stimulating appetite and reducing fat utilization.6 It is secreted by the stomach.7 Ghrelin sends a signal to the hypothalamus, which then stimulates appetite. Although it is expected that ghrelin levels would be higher in obese individuals since it is the hunger hormone, it has been seen that ghrelin levels are actually decreased in obese humans.6

Environment

Many environmental factors are at play in the development of obesity, namely high-fat diets and low levels of physical activity (2). The WHO reports that worldwide, 23 percent of adults and 81 percent of adolescents do not get enough physical activity to prevent chronic diseases such as obesity (1). Furthermore, in developed nations, there has been an increase in food availability, large portion sizes or “super-sizing” of commercially available foods as well as the rise of fast-food restaurants, which can all lead to overconsumption (2). There is also an indication that people living in poverty have a higher risk of weight gain (2). This may be because impoverished areas, often called “food deserts”, have poor access to fresh foods (2). Additionally, the low cost of fast-food restaurants is a much more affordable option for many people of lower socioeconomic status (2).

some bar graph

Genetics

Family history is a known risk factor of obesity and is an important predictor of obesity in children (3). However, the heritability component of obesity is still not well understood.

Non-syndromic monogenic obesity is an extreme form of the disease that results from a single gene mutation (3). One such mutation that leads to this type of obesity is a frameshift homozygous mutation in the leptin (LEP) gene (3). This results in a truncated version of leptin, in turn leading to a leptin deficiency (3). Clinical manifestations of the LEP mutation include rapid weight gain in early childhood, excessive hunger and intolerant behaviour when presented with food (3). These symptoms can be reversed through leptin therapy (3).

Much of obesity’s genetic component is said to be attributed to multiple genetic variations contributing a small part, otherwise known as polygenic obesity (3). One gene that has been associated with polygenic obesity is the fat mass and obesity-associated (FTO) gene (3). There is evidence that suggests that there is a relationship between common single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the FTO gene and developing Type 2 diabetes, mediated by an increase in the BMI (3). Furthermore, FTO is strongly associated with increased hip circumference, weight and risk of childhood obesity (3).

Fad Diets

A fad diet is defined as a promise of quick weight loss through unconventional techniques. (Caufield). The problem with these diets is they are generally very unhealthy, and have no scientific backing to support them. One of the earlier studies done that examined fad diets was conducted by Mirkin and Shore and examined “The Beverly Hills Diet.” This diet was based around three principle claims. Firstly, “As long as food is fully digested, fully processed through the body, you will not gain weight. It’s only undigested food, food that is “stuck” in your body, for whatever reason, that accumulates and becomes fat.” Secondly, “Most enzymes do not work simultaneously… Many cancel one another out in our digestive systems.” And finally “Enzymes presented in certain fruits make hard to digest foods less fattening.” This along with many other absubities were sold to consumers by, in the case of the Beverly Hills Diet, an individual who is not a doctor nor a dietitian (Mirkin and Shore). All these claims are to any medical professional or dietitian quite obscure– of course fat must be digested into the body to accumulate, enzymes do not cancel each other out, and certain enzymes cannot take away the fat content of another food. Regardless, the promise of a “quick-fix” for an individual who is hoping to lose weight is extremely palatable as it appears to require less work than the alternative, proven weight loss techniques– consume less calories than you burn and exercise.

Gwyneth Paltrow and GOOP

Celebrities are given a great deal of viability when promoting diets, even if they have no idea what is going on. One of the more recent cases of this is seen within GOOP– a company created by actress Gwyneth Paltrow that gives health and lifestyle advice to other individuals.

Dr. Timothy Caulfield is a professor and public health at the University of Alberta. He is also the director of their Health Law Institute. Dr. Caulfield set out to examine the diets and their discrepancies set out by Paltrow in his book called “Is Gwyneth Paltrow wrong about everything?” The diet Paltrow promotes the most is called “The Clean Cleanse.” The program claims the human body accumulates toxins from the air around us and the food we eat over time, and therefore we need to rid our body of these toxins in some ways. Although quite the appealing idea, this concept of toxin build up in our bodies is not scientifically proven (caulfield). Our bodies are constantly detoxifying through sweating and urinating, and no diet can somehow change this process. Another avid point made by the cleanse team is that these toxins lead to “fatigue” of our adrenal gland, which lead to “sky high adrenals” which stress our bodies and cause us to put on weight. Once again, there is no scientific basis to this claim. Studies do show that eating healthier is associated with better affect and lower depression (ie. higher fruit and vegetable diets). There is no tie however to our adrenal glands being stressed and that causing us to gain weight. The program generally lasts 21 days, and from experience Dr. Caulfield has claimed he did in fact lose weight, but not from “detoxification” but more simply from a lack of calories being consumed over the period of time, not from a magical diet that cuts out wheat and sugars (as the Clean Cleanse does).

http://blog.cleanprogram.com/elimination-diet This is a link to the program diet. There is no rhyme or reason to any of these foods being validated on the program list, but people lose weight and therefore the program continues to grow.

The unfortunate reality of these crash diets is that only 5% of individuals will actually keep the weight off for any extended period of time. This is why a continuation of healthy eating and living is the truly only effective way to lose weight and maintain it.

Treatments

When undergoing treatment options for obesity, the combination therapy involving exercise, behavioural and dietary modifications are recommended by physicians due to their proven effectiveness and least amount of side effects. When undergoing weight loss therapy a maximum of 10% of total body weight should be lost within a 6 month period.

Diet

The main component to the treatment of obesity is to have healthier modifications to the individuals diet. The goal for dietary therapy as well as each of the other lifestyle changes is to have the energy intake be lower than the energy expenditure, essentially having a negative energy balance (1).

There are many types of diets prescribed to obese individuals, the main ones that are studied are the low-fat diet, very low-fat diet, high protein diet and low carbohydrate diet. The low-fat diet restricts individuals to consume 20-35% of their dietary calories in fats (1). These diets are the most studied of all dietary approaches to weight loss and have shown a significant weight decrease in individuals following this diet. The very low-fat diet restricts individuals to consume less than or equal to 20% of their dietary calories from fats (1). These diets are primarily plant based, studies have shown that participants following the Ornish diet (a very low-fat diet) experienced significant weight loss and improvements in CVD risk factors (1).

The high protein diet is when the intake of dietary protein is higher than 25% of the individuals daily calories. Studies have proven the efficacy of both weight loss and improvements in body composition with this diet (1). Individuals following a high protein diet, decrease their waist circumference, waist to hip ratio and intra-abdominal adipose tissue (1). This diet is of great interest due to the fact that certain chronic diseases are associated with these body composition (1).

Excercise

The first component to the weight loss therapy is to treat obesity by increasing the levels of the obese individual’s physical activity (2). The goal for any weight loss program is to have a negative energy balance at the end of the day, so the individual should aim to increase their energy expenditure and physical activity is an excellent way to do so (2). Physical activity is linked to increased weight loss and weight management (2).

It is important to take note that not every exercise routine responds the same way to each individual, one type may be more effective at reducing weight for some individuals than others. There are a variety of different exercise routines which can involve running, walking, rowing, free weights or a combination of any of these(2). It is very difficult for obese individuals to lose weight due to all of the variables associated with their weight gain and because of this it can be just as much of a mental battle as a physical one, so it is recommended that the individuals acquire a trainer that can help them with their exercise regime as well as help set realistic goals throughout the process. A meta-analysis done by Shaw et al., 2006 showed that exercise is an excellent weight loss intervention and the effects are improved with the combination of dietary modifications as well (2). They also found that exercise was able to alleviate secondary symptoms associated with obesity like cardio vascular disease, blood pressure (2).

Behavioural Modifications

Behavioural therapy has recently started to become added into the therapies alongside the exercise and dietary modifications. This is because obesity is thought to be a result of maladaptive eating patterns and exercise habits and that these behaviours can be modified with specific interventions which will lead to weight loss (3). The main goal for behavioural therapy is to help individuals with obesity develop skills that can help them achieve and maintain a healthier body weight. Cognitive behavioral therapy has become popular over the past two decades (3). A few of the common components used in behavioural therapy are: (3) · Self – monitoring: this includes keeping a daily food log of all of the meals the individual has had throughout the day. · Stimulus control: the purpose for this component is to alter the environment for the individual in order to avoid over eating. This is to basically eliminate energy dense foods from the home and replace it with nutrient dense foods. · Goal setting: setting realistic goals for both the short and long term. · Behavioural contracting: reinforcing of good behaviours. · Social support: it has been shown that behavioural modifications have become more sustainable in the long term with social support. Receiving encouragement from family and friends can be effective with losing more weight.

Pharmaceuticals

Another line of treatment for obesity is to use medication in combination with the lifestyle changes mentioned above. Two popular obesity medications are in the classes of lipase inhibitors and appetite suppressants.

Lipase inhibitors function to prevent the absorption of fats from the individuals diet therefore reducing caloric intake. Orlistat is a common lipase inhibitor used to combat obesity, it is a derivative of lipstatin which is a natural inhibitor of pancreatic lipases (4). Orlistat has been proven with definitive results to work with weight loss. A study showed that when prescribed orlistat combined with lifestyle changes individuals lost been 3% and 9% of their initial weight within one year compared to a control group who only underwent lifestyle changes (5).

Appetite suppressants are also used to help with weight loss in combination with lifestyle changes. Phentermine is the most widely prescribed obesity medication in adults, it is a psychostimulant drug which is used as an appetite suppressant by affecting the central nervous system (6). This drug is only permitted to be used for 3 months at a time alongside exercise and nutritional therapy or it may cause side effects in the cardiovascular system, gastrointestinal system and the central nervous system (6).

A retrospective study wanted to test the efficacy of the drug with adolescents. They had 25 individuals who were medicated with phentermine and they matched them with a control individual who was receiving only the standard of care (7). They found at each measurement date 1,3 and 6 months that there was a significant difference in weight loss between groups and there was no difference in blood pressure between groups (7).

Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric surgery is a weight loss procedure which aims to decrease the size of the obese individuals stomach by either a gastric band or the removal of a portion of the stomach (8). It is not recommended for individuals below a BMI of 40 to undergo bariatric surgery. Post-surgery patients are only able to have a clear liquid diet which is continued until the gastro intestinal tract is healed (8). Once that stage is complete a blended diet where foods high in protein are recommended alongside soft meals. Finally, once recovery is complete the patient is able to eat all types of foods again, but they are restricting from over eating due to the surgery. If they over eat they will reach the capacity of their stomach which will cause discomfort (8).

Studies have proven the effectiveness of this procedure in causing significant weight loss in the long term as well as secondary effects like recovery from diabetes, CVD and reduction in mortality (9). There is great debate at the moment whether individuals with type 2 diabetes shoul be given bariatric surgery because of the success it has with diabetes remission; more research needs to be done on the topic with the focus group as well as the proper timing for the most effective treatment (9).

Gene therapy – Leptin deficiency

Gene therapy is a hot topic in the science community at the moment, and advances in this technology and the understanding of the molecular basis for obesity have allowed for researchers to design therapies to tackle this disease. The main goal for gene therapy is to increase gene products in favour of fat loss and energy expenditure(10).

The most studied gene directly linked to obesity is leptin, which plays a role in appetite and energy expenditure. It is thought that obese individuals have a mutation within this gene. A defect in the ob gene coding for leptin has been linked to sever obesity (10). It was found that mice who homozygous for this defect in the leptin gene ate excessively and developed obesity. Researchers found that the delivery of leptin into the brain though a recombinant virus into mice was able to generate long term beneficial effects with body weight (10). Another study aimed to show that leptin sensitivity was also crucial with the weight loss with mice, because HFD mice were unresponsive with the treatment but when they were delivered leptin receptor gene reduction in body weight was seen(10).

References

1. Ng, M., Fleming, T., Robinson, M., Thomson, B., Graetz, N., & Margono, C. et al. (2014). Global, regional, and national prevalence of overweight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013.The Lancet, 384(9945), 766-781. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60460-8

2. Seidell, J. & Halberstadt, J. (2015). The Global Burden of Obesity and the Challenges of Prevention. Annals Of Nutrition And Metabolism, 66(2), 7-12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000375143

3. WHO: Global Database on Body Mass Index. (2017). Apps.who.int. Retrieved 1 February 2017, from http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html

4. Child & Teen BMI | Healthy Weight | CDC. (2017). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 1 February 2017, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html

5. Jitnarin, N., Poston, W., Haddock, C., Jahnke, S., & Tuley, B. (2012). Accuracy of body mass index-defined overweight in fire fighters. Occupational Medicine, 63(3), 227-230. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqs213

6. Spiegelman, B. & Flier, J. (2001). Obesity and the Regulation of Energy Balance. Cell, 104(4), 531-543. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00240-9

7. Pietiläinen, K., Kaprio, J., Borg, P., Plasqui, G., Yki-Järvinen, H., & Kujala, U. et al. (2008). Physical Inactivity and Obesity: A Vicious Circle. Obesity, 16(2), 409-414. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/oby.2007.72

8. Cohen-Cole, E. & Fletcher, J. (2008). Is obesity contagious? Social networks vs environmental factors in the obesity epidemic. Journal Of Health Economics, 27(5), 1382-1387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.04.005

9. Masuo, K. (2000). A family history of obesity, a family history of hypertension and blood pressure levels. American Journal Of Hypertension, 13(6), S164. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0895-7061(00)01125-0

10. Weaver, J. (2008). Classical Endocrine Diseases Causing Obesity. Obesity And Metabolism, 212-228. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000115367

11. Schwartz, T., Nihalani, N., Jindal, S., Virk, S., & Jones, N. (2004). Psychiatric medication-induced obesity: a review. Obesity Reviews, 5(2), 115-121. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-789x.2004.00139.x

12. Dare, S., Mackay, D., & Pell, J. (2015). Relationship between Smoking and Obesity: A Cross-Sectional Study of 499,504 Middle-Aged Adults in the UK General Population. PLOS ONE, 10(4), e0123579. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0123579

13. Vermeulen, A. (2005). The epidemic of obesity: Obesity and health of the aging male. The Aging Male, 8(1), 39-41. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13685530500049037

14. Schumann, N., Brinsden, H., & Lobstein, T. (2014). A review of national health policies and professional guidelines on maternal obesity and weight gain in pregnancy. Clinical Obesity, n/a-n/a. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/cob.12062

15. Why Is Sleep Important? - NHLBI, NIH. (2017). National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Retrieved 1 February 2017, from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/sdd/why

16. Gurevich-Panigrahi, T., Panigrahi, S., Wiechec, E., & Los, M. (2009). Obesity: pathophysiology and clinical management. Current Medical Chemistry, 16, 506-521. Retrieved from http://liu.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:583167/FULLTEXT01.pdf

17. Odegaard, J., & Chawla, A. (2012). Adipose tissue metabolism in the obese. TheScientist. Retrieved 18 January 2017, from http://www.the-scientist.com/?articles.view/articleNo/33653/title/adipose-tissue-metabolism-in-the-obese/

18. Kahn, B. B., & Flier, J. S. (2000). Obesity and insulin resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 106(4), 473–481.

19. Després, J., & Marette, A. (1999). Obesity and Insulin Resistance. Insulin Resistance, 51-81. doi:10.1007/978-1-59259-716-1_4

20. Klok, M. D., Jakobsdottir, S., & Drent, M. L. (2007). The role of leptin and ghrelin in the regulation of food intake and body weight in humans: a review. Obesity Reviews, 8(1), 21-34. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789x.2006.00270.x

21. Kaszmi, A., Sattar.A., Hashim, R., Khan., S.P.., Younus, M., Khan, F.A. (2013). Serum Leptin values in the healthy obese and non-obese subjects of Rawalpindi. J Pak Med Assoc. 63(2), 245-8

22. Tschop, M., Weyer, C., Tataranni, P. A., Devanarayan, V., Ravussin, E., & Heiman, M. L. (2001). Circulating Ghrelin Levels Are Decreased in Human Obesity. Diabetes, 50(4), 707-709. doi:10.2337/diabetes.50.4.707

23. Walley, A.J., Blakemore, A.I.F. & Froguel, P. (2006). Genetics of obesity and the prediction of risk for health. Human Molecular Genetics. Retrieved 27January, 2017, from https://academic.oup.com/hmg/article/15/suppl_2/R124/626082/Genetics-of-obesity-and-the-prediction-of-risk-for

24. Rankinen, T., Zuberi, A., Chagnon, Y.C., Weisnagel, S.J., Argyropoulos, G., Walts, B., Perusse, L., & Bouchard, C. (2006). The human obesity gene map: the 2005 update. Obesity, 14(4), 529-644.

25. Pi-Sunyer, F. X., Becker, D. M., Bouchard, C., Carleton, R. A., Colditz, G. A., Dietz, W. H., … & Higgins, M. (1998). Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 68(4), 899-917.

26. Lau, D. C., Douketis, J. D., Morrison, K. M., Hramiak, I. M., Sharma, A. M., Ur, E., & members of the Obesity Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Panel. (2007). 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 176(8), S1-S13.

27. Poirier, P., & Després, J. P. (2001). Exercise in weight management of obesity. Cardiology clinics,19(3),459-470.

28. Hey, H., Petersen, H. D., Andersen, T., & Quaade, F. (1987). Formula diet plus free additional food choice up to 1000 kcal (4.2 MJ) compared with an is energetic conventional diet in the treatment of obesity. A randomised clinical trial. Clinical Nutrition,6(3),195-199.

29. Lau, D. C., Douketis, J. D., Morrison, K. M., Hramiak, I. M., Sharma, A. M., Ur, E., & members of the Obesity Canada Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Panel. (2007). 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 176(8), S1-S13.

30. Toubro, S., & Astrup, A. (1997). Randomised comparison of diets for maintaining obese subjects' weight after major weight loss: ad lib, low fat, high carbohydrate diet fixed energy intake. Bmj,314(707329.

31. 9 Popular Weight Loss Diets Reviewed by Science. (2016, October 04). Retrieved January 27, 2017, from https://authoritynutrition.com/9-weight-loss-diets-reviewed/

32. Poirier, P., & Després, J. P. (2001). Exercise in weight management of obesity. Cardiology clinics, 19(3), 459-470.

33. Tremblay, A., Nadeau, A., Despres, J. P., St-Jean, L., Theriault, G., & Bouchard, C. (1990). Long-term exercise training with constant energy intake. 2: Effect on glucose metabolism and resting energy expenditure. International journal of obesity, 14(1), 75-84.

34. Gwinup, G. (1987). Weight loss without dietary restriction: efficacy of different forms of aerobic exercise. The American journal of sports medicine, 15(3), 275-279.

35. Pate, R. R., Pratt, M., Blair, S. N., Haskell, W. L., Macera, C. A., Bouchard, C., … & Kriska, A. (1995). Physical activity and public health: a recommendation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the American College of Sports Medicine. Jama, 273(5), 402-407.

36. Nozaki, T., Sawamoto, R., & Sudo, N. (2013). Cognitive behavioral therapy for obesity. Nihon rinsho. Japanese journal of clinical medicine, 71(2), 329-334.

37. Cooper, Z., Fairburn, C. G., & Hawker, D. M. (2003). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of obesity: A clinician's guide. Guilford Press.

38. Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. (2002). The diabetes prevention program (DPP). Diabetes care, 25(12), 2165-2171.

39. Look AHEAD Research Group. (2003). Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes): design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Controlled clinical trials,24(5), 610-628.

40. Renjilian, D. A., Perri, M. G., Nezu, A. M., McKelvey, W. F., Shermer, R. L., & Anton, S. D. (2001). Individual versus group therapy for obesity: effects of matching participants to their treatment preferences. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 69(4), 717.

41. Wrotniak, B. H., Epstein, L. H., Paluch, R. A., & Roemmich, J. N. (2004). Parent weight change as a predictor of child weight change in family-based behavioral obesity treatment. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 158(4), 342-347.

42. Epstein, L. H., Roemmich, J. N., Stein, R. I., Paluch, R. A., & Kilanowski, C. K. (2005). The challenge of identifying behavioral alternatives to food: clinic and field studies. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30(3),201-209

43. Guerciolini, R. (1997). Mode of action of orlistat. International journal of obesity and related metabolic disorders: journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity, 21, S12-23.

44. Finer, N. (2002). Sibutramine: its mode of action and efficacy. International Journal of Obesity, 26(S4), S29.

45. Davidson, M. H., Hauptman, J., DiGirolamo, M., Foreyt, J. P., Halsted, C. H., Heber, D., … & Heymsfield, S. B. (1999). Weight control and risk factor reduction in obese subjects treated for 2 years with orlistat: a randomized controlled trial. Jama, 281(3), 235-242.

46. James, W. P. T., Astrup, A., Finer, N., Hilsted, J., Kopelman, P., Rössner, S., … & STORM Study Group. (2000). Effect of sibutramine on weight maintenance after weight loss: a randomised trial. The Lancet, 356(9248), 2119-2125

47. Sjöström, L., Lindroos, A. K., Peltonen, M., Torgerson, J., Bouchard, C., Carlsson, B., … & Sullivan, M. (2004). Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. New England Journal of Medicine, 351(26), 2683-2693.