This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Dissociative Identity Disorder Powerpoint

PowerPoint File:dissociative_identity_disorder-_presentation.pptx

Dissociative Identity Disorder

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), is also commonly referred to as multiple personality disorder. It is a very complex disorder characterized by the coexistence of multiple separate identities (Kluft, 1996). DID commonly develops after the occurrence of some form of trauma in childhood. However, as a person with DID grows older, the multiple personalities may grow more complex, as the individual affected may combine posttraumatic events with fantasy to create more intricate personalities (Kluft, 1996).

Diagnosis

Physicians must rule out possible physical disease or physiological effects of a substance (e.g.: head injury or intoxication) that may be causing symptoms of memory loss and a sense of unreality (Nurcombe, 2008). Once physical conditions are ruled out, a psychiatrist can diagnose dissociative disorders by assessing observed or reported symptoms and life history. Often, repeat psychotherapy assessments are conducted to see how a patient is progressing (Nurcombe, 2008).

Defining Feature

DID is the disruption of identity caused by two or more distinct personality states or an experience of possession (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Diagnostic Criteria according to DSM-5

- A. Disruption of identity characterized by 2 or more distinct personality states, which may be described in some cultures as an experience of possession. The disruption in identity involves marked discontinuity in sense of self and sense of agency, accompanied by related alterations in affect, behaviour, conciousness, memory, perception, cognition, and/or sensory-motor functioning. These signs and symptoms may be observed by others or reported by the individual.

- B. Recurrent gaps in the recall of everyday events, important personal information, and/or traumatic events that are inconsistent with ordinary forgetting.

- C. The symptoms cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

- D. The disturbance is not a normal part of a broadly accepted cultural or religious practice. Note: In children, the symptoms are not better explained by imaginary playmated or other fantasy play.

- E. The symptoms are not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., blackouts or chaotic behaviour during alcohol intoxication) or another medical condition (e.g., complex partial seizures).

This information is quoted from The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual for Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Dissociative Flashbacks and Associated Features

Individuals with DID tend to report dissociative flashbacks. During dissociative flashbacks, the individual experiences a previous event as if it were occurring in the present. The experience is relived with a change of identity, disorientation, or a partial or complete loss of contact with current reality. The flashback is followed with amnesia about the content of the flashback. Individuals diagnosed with DID tend to have comorbid depression, anxiety, sleeping disorders and eating disorders. Substance abuse, self-harm and non-epileptic seizures are common in DID patients (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Epidemiology

Prevalence

A study conducted by the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation found the rate of DID to be about 1-3% in the general population (Johnson, 2011). However, this study may have underrepresented the cases of DID, as it is often misdiagnosed or undiagnosed. For example, in a prevalence study conducted by Foote, 5% of his sample size was diagnosed with DID, however in reality 29% actually had DID (Foote, 2006). Furthermore DID may be misdiagnosed as other disorders such as borderline personality disorder, schizophrenia, or psychosis. One reason that DID is often misdiagnosed and underdiagnosed is because it shares many different symptoms with other disorders, and thus psychiatrists may attribute the symptoms to another disorder (Johnson, 2011).

Demographics

The most common age range for those suffering from DID is between 22.8 years to 34.5 years, with the median age being approximately 31.3 years (Foote, 2018). Through the conduction of eleven different studies, it was found that 89% of those suffering from DID were women, while only 11% were men (Foote, 2018). However, this statistic may show an over-representation of women, because these studies were conducted in psychiatric facilities, and women are more likely than men to seek psychiatric help.

Common Symptoms

- Amnesia- Amnesia is typically around a period in childhood with a focus on traumatic events. The host and alters have no memory of other alters due to amnesic barriers separating alters. Amnesia follows dissociative flashbacks.

- Anxiety

- Auditory hallucinations- Hallucinations include crying, muttering, self-depracatory remarks.

- Depression

- Fugue episodes- May find themselves at some destination with no knowledge of journey.

- Insomnia and nightmares- Alters may keep host and other alters awake.

- Lost time “blackouts”- The host loses time when the alter(s) take over.

- Low self-esteem

- Mood swings- May have several mood changes in a day.

- Numbness- Individual may feel distant or detached from self.

- Self-harm- May be inflicted to prevent switching, have sense of control, or return to a feeling of reality.

- Somatoform symptoms

- Suicide attempts- Attempts are often in rapid succession and may be without the host’s awareness (Ringrose, 2018).

Life with DID

Generally, people with DID can function normally. However, an experience of extreme emotion especially associated with childhood trauma can trigger a switch. When there is a perceived threat, patients tend to switch to an alter who is more competent to handle the situation. DID patients tend to avoid situations, people and environments that may remind them of a childhood trauma linked to their disorder. Coping with comorbid mental health disorders and symptoms of DID is important to maintaining the individual’s quality of life. Long-term supportive treatment helps individuals manage their symptoms and minimize strain on relational, marital, family, parenting, occupational and professional life (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Genetic Causes

There are many complex factors that contribute to DID. However, many animal and psychophysiological studies conclude that many types of personality disorders are influenced genetically, in particular the schizotypal and antisocial personal disorder. Furthermore, DID patients who experience early stress during childhood show association with changes in the structure of the hippocampus and the amygdalar volumes. This suggests that one’s genetic predisposition to smaller hippocampus and amygdalar volumes may lead to the development of DID. One of the predisposing factors of DID is a natural, inborn capacity to dissociate. This is the biological determinant of DID. Although no twin studies have yet been undertaken due to the difficulties in sampling, there is evidence that DID may be trangenerational. It has been reported and/or observed that there is evidence of dissociative phenomenon in the family histories of 18 multiple case.

Environmental Causes

There is a relationship between detachment in infancy and increased vulnerability to dissociative disorder. The mothers of dissociative patients reported to have suffered the loss of a significant other in the first two years of their lives. In addition, childhood trauma, physical and sexual abuse in early childhood, latency and adolescence were shown to be significant predictors of self-mutilation and suicidality. In a study by Collin A. Ross and colleagues, 102 individuals with clinical diagnoses of DID were interviewed with Dissociative Disorders Interview Schedule (DDIS). The result was that the rates of childhood sexual abuse varied across five large series of cases, but always within the same range. This indicates that there are consistent findings of high rates of childhood trauma such as physical or sexual abuse or both. For the majority of the subjects in the study, the abuse started before the age of 5. In a larger pool of 388 cases of DID, 91.2% of the patients had been physically or sexual abused.

Anatomic Abnormalities

There are 3 distinct hypotheses that have been supported by research data obtained through various means of data collection. These hypotheses each attribute the symptoms of dissociative identity disorder to a structure of the brain. Respectively, these are the orbitofrontal hypothesis, cortico-limbic hypothesis, and finally the temporal hypothesis (Dorahy et al, 2014). Furthermore, each specific method of data collection tends to support a single hypothesis.

Orbitofrontal Hypothesis

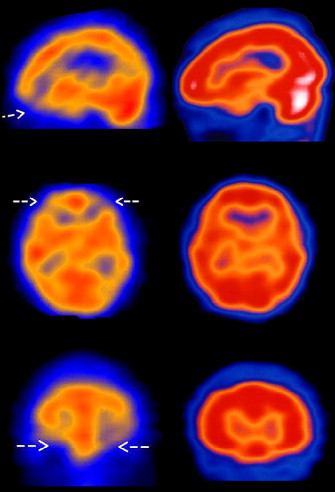

Single Photon Emission Computerised Tomography (“SPECT”) studies suggest data that supports the orbitofrontal hypothesis. To expand the orbitofrontal cortex has been postulated to be vital for a sense of self and emotional attachment (Sar et al, 2007). A SPECT study done by Sar et al shows that DID patients exhibit reduced perfusion (blood flow) to the orbitofrontal cortex of the brain as depicted in Figure 1. The orbitofrontal cortex has been shown to inhibit the development of dissociative identities and so individuals with reduced blood flow to this region are likely to develop DID (Sar et al, 2007).

Cortico-Limbic Hypothesis

Alternatively, studies that used brain imaging techniques such as fMRI and PET associate symptoms of DID with the cortico-limbic system. This system includes many structures including the hippocampus and amygdala. Suggestive evidence regarding the hippocampus and amygdala has been published by in a study involving female DID patients. Data in Figure 2 shows that patients with DID have reduced hippocampal and amygdalar volumes (Vermetten et al, 2007). These structures are involved with long term memory storage and fear/anxiety responses respectively (Vermetten et al, 2007). Furthermore, larger volumes of these structures have been shown to serve a protective role against early life trauma and smaller volumes predispose individuals to disorders such as DID (Vermetten et al, 2007).

Temporal Hypothesis

Lastly, EEG and QEEG studies have revealed that there is also a correlation between abnormal electrical activity in the temporal lobe and DID symptoms. In a case study analysis done by Mesulam MM in 1981, 12 patients were analyzed and selected for abnormal temporal lobe activity as well as psychological dysfunction. Among these 12, 7 presented with defining features of dissociative identity disorder/multiple personality disorder whereas the other 5 reported feelings of a supernatural possession. Dissociative identities are reported as possession in some cultures, however this has not been clarified in the study. This shows support for the temporal lobe hypothesis. The temporal lobe has been thought to have a function of integrating affective tone with sensory information and perception (Mesulam, 1981). To clarify, affective tone is the state of mind of the individual and impacts the way in which a person is affected by an event (happy, sad, angry, etc). Whilst disruptions in the temporal lobe can sometimes lead to irregular character traits, it can also lead to more dramatic effects such as dissociative states of identity (Mesulam, 1981).

Treatments

Dissociative Identity Disorder is a complex disorder that cannot be treated by pharmaceutical drugs alone. This is due to the fact that this disorder is unique to each individual. Each individual affected by this disorder develops unique identities and thus it is very difficult to design a standard form of treatment that will work for everyone. Thus, treatment for DID is most often offered in the form of therapy. One such therapy is known as the two-standard therapeutic approach which consists of the restoration and integration phase. The restoration phase involves selecting a single identity and making that the host identity (Bayne, 2002). Most often this is the identity an individual had before they were diagnosed with DID. The integration phase involves combining multiple alters into a single identity (Bayne, 2002). If more than one identity provides positive benefits for the individual, integrating more than one identity together is a much better solution. Both of these approaches require repetitive practice effects to allow the identity to fixate.

Other research indicates that a phasic trauma treatment model along with expert consensus guidelines can create positive results within individuals diagnosed with DID (Brand et al., 2009). The triphasic model for DID treatment was introduced by Judith Herman who is an American psychiatrist. This model consists of three stages and is often used for patients who develop DID due to a traumatic event. Stage 1 involves establishing safety and stability by preventing DID patients from causing self-harm, making sure that they avoid abusive relationships, and have adequate support (Dorahy et al., 2014). Stage 2 is focused on maintaining stability while resolving trauma related emotions by helping DID patients control their emotions while they overcome their fear of the traumatic events they experienced. (Dorahy et al., 2014). Stage 3 involves integrating multiple identities by helping DID patients establish themselves once again into society (Dorahy et al., 2014). Some DID experts also recommended adding interventions to each of the stages (Brand et al., 2012). Some recommended interventions included providing psychoeducation, increasing awareness and tolerance of emotion, and managing stressors and relationships (Dorahy et al., 2014). A longitudinal international study consisting of 292 therapists and 280 DID patients from 19 countries reported patients showing significant reductions in dissociation, distress, depression, suicide attempts, and aggressive behaviour over a 30-month period (Dorahy et al., 2014). The data was collected from patient’s responses to survey questions and were collected four times over the course of the study (Dorahy et al., 2014). Additionally, it was observed that younger patients self-destructive and suicidal behaviours changed more rapidly than adults (Myrick et al., 2012). This finding shows that treatment at an early age may produce more beneficial results.

Some antipsychotic drugs that block dopamine and serotonin receptors have been administered to patients with severe DID along with psychotherapy (Gentile et al., 2013). However, these drugs alone are not sufficient to treat dissociation and therefore patients require therapy for treating DID. These drugs can simply reduce the symptoms of DID but not treat the disorder completely.

Legal implications & Case studies

Although DID is believed to be uncommon, there have been some cases of DID brought up in court rooms. It has been used as a defence in cases ranging from drunk driving, kidnapping, theft and even murder, in extreme cases.

Juanita Maxwell

Juanita Maxwell worked as a maid in a Florida Hotel. In 1979 she was accused of murdering a hotel guest using a lamp. Howeve during the trial, her lawyer accused her alternate personality Wanda, of committing the murder (James, 2008). Juanita claimed that the guest had refused to return a pen that she had borrowed, and thus Juanita had barged into her hotel room and killed her. She also claimed that she had 7 alternate personalities. It was an interesting case for the court that had to consider whether or not DID was a viable explanation for the murder. Ultimately they sided with Juanita, and she was declared “not guilty due to insanity”. She was placed in care at Florida State Hospital, where she was prescribed Haloperidol as a medication (James, 2008). This was an important legal case because it was one of the first court cases in which the jury had to consider the consequences of DID.

References

Association, A. P. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

Bayne, T. J. (2002). Moral Status and the Treatment of Dissociative Identity Disorder1. The Journal of medicine and philosophy, 27(1), 87-105.

Brand, B. L., Armstrong, J. G., Loewenstein, R. J., & McNary, S. W. (2009). Personality differences on the Rorschach of dissociative identity disorder, borderline personality disorder, and psychotic inpatients. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 1(3), 188.

Brand, B. L., Classen, C. C., McNary, S. W., & Zaveri, P. (2009). A review of dissociative disorders treatment studies. The Journal of nervous and mental disease, 197(9), 646-654.

Dorahy, M. J., Brand, B. L., Şar, V., Krüger, C., Stavropoulos, P., Martínez-Taboas, A., … & Middleton, W. (2014). Dissociative identity disorder: an empirical overview. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 48(5), 402-417.

Foote, B. (2018). Dissociative identity disorder: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, course, assessment, and diagnosis. Up to Date. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/dissociative-identity-disorder-epidemiology-pathogenesis-clinical-manifestations-course-assessment-and-diagnosis

Foote, B, Smolin, Y, Kaplan, M, Legatt, M.E., Lipschitz, D. (2006). Prevalence of dissociative disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 163(4):623-9.Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16585436

Forrest, K. A. (2001). Toward an etiology of dissociative identity disorder: A neurodevelopmental approach. Consciousness and Cognition, 10(3), 259-293.

Gentile, J. P., Dillon, K. S., & Gillig, P. M. (2013). Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for patients with dissociative identity disorder. Innovations in clinical neuroscience, 10(2), 22.

James, D. (1998). Multiple personality disorder in the courts: A review of the North American experience, The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry, 9:2, 339-361, DOI: 10.1080/09585189808402201

Johnson, K. (2011). The Problem of Prevalence- How common is DID? Positive Outcomes for Dissociative Survivors. Retrieved from https://information.pods-online.org.uk/the-problem-of-prevalence-how-common-is-did/

Kluft, R. P. (1987). Childhood antecedents of multiple personality. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric.

Mesulam, M. M. (1981). Dissociative states with abnormal temporal lobe EEG: Multiple personality and the illusion of possession. Archives of Neurology, 38(3), 176-181.

Myrick, A. C., Brand, B. L., McNary, S. W., Classen, C. C., Lanius, R., Loewenstein, R. J., … & Putnam, F. W. (2012). An exploration of young adults' progress in treatment for dissociative disorder. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 13(5), 582-595.

Nurcombe, B. (2008). Chapter 24. Dissociative Disorders. In M. H. Ebert, P. T. Loosen, B. Nurcombe, & J. F. Leckman (Eds.), CURRENT Diagnosis & Treatment: Psychiatry (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies. Retrieved from accessmedicine.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=3287667

Ringrose, J. L. (2018). Understanding and Treating Dissociative Identity Disorder (or Multiple Personality Disorder). Routledge.

Ross, C. A., Miller, S. D., Bjornson, L., Reagor, P., Fraser, G. A., & Anderson, G. (1991). Abuse Histories in 102 Cases of Multiple Personality Disorder. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry,36(2), 97-101. doi:10.1177/070674379103600204

Sar, V., Unal, S. N., & Ozturk, E. (2007). Frontal and occipital perfusion changes in dissociative identity disorder. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 156(3), 217-223.

Vermetten, E., Schmahl, C., Lindner, S., Loewenstein, R. J., & Bremner, J. D. (2006). Hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in dissociative identity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(4), 630-636.