This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Anorexia

Overview

Introduction

Anorexia is a life threatening mental illness that typically begins around puberty but can occur at any age. It is characterized by persistent behaviours that interfere with maintaining an adequate weight for health, a powerful fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, disturbance in how the person experiences their weight and shape and the individual not fully appreciating the seriousness of their condition. If these characteristics are seen over a period of a least three months an individual can be diagnosed with anorexia (Nedic, 2014).

Persistent behaviours that interfere with maintaining an adequate weight for health includes: restricting food, compensating for food intake through intense exercise, and/or purging through self-induced vomiting or misuse of medications like laxatives, diuretics, enemas, or insulin. In the past anorexia used to be specifically associated with weight loss, making it difficult to recognize in children and adolescents. Weight gain is needed in children and adolescents in order to support healthy growth and development. Therefore, failing to gain weight or grow is just as concerning as weight loss (Nedic, 2014).

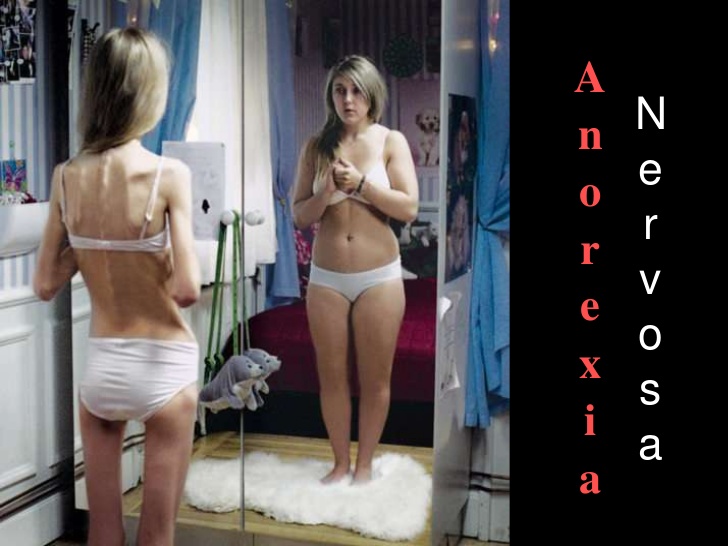

The powerful fear of gaining weight or becoming fat is common in individuals with anorexia. Individuals may feel this fear ever if they are maintaining a weight that is too low for their health. Often this fear will result in individuals using a variety of techniques to evaluate their body size or weight - behaviour known as body checking. Frequent weighing, obsessive measuring of body parts and the persistent use of mirrors to check for “fat” are common techniques used to body check (Nedic, 2014).

There is a disturbance in how the person experiences their weight and shape meaning that the person overestimates their body size, they usually evaluate it negatively. Individuals feel that their weight and shape matter more than anything else about them (Nedic, 2014).

Typically, an individual with anorexia does not fully appreciate the seriousness of their condition as it has been linked to cardiac arrest, suicidality, and other causes of death. Anorexia was previously associated with the loss of menstrual periods which made it difficult or impossible to identify in males or in pre-pubescent children or teens, however this is no longer necessary for diagnosis (Nedic, 2014).

History

Progeria is an extremely rare genetic disease of childhood characterized by dramatic, premature aging with death occurring on average at the age of 13, usually from heart attack or stroke (Kashyap et al., 2014). Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome (HGPS) is the most severe form of the disease and the classic type. The disease was named after the doctors who first described it in England; in 1886 by Dr. Jonathan Hutchinson and in 1897 by Dr. Hastings Gilford. The term progeria is derived from the Greek work geras, meaning old age (DeBusk, 1972).

In 1886, the syndrome was first reported by Hutchinson of a 6-year-old boy whose overall appearance was that of an old man. Hutchinson described the case as “congenital absence of hair and its appendages” (DeBusk, 1972). It was a year later that Gilford described a second patient with similar clinical findings. To date, there are only 100 patients with HGPS that have been described in literature (Kashyap et al., 2014). These two boys were further described in 1897 and 1904 by Gildford, who was the one to proposal the term “progeria” and described the post-mortem characteristics (DeBusk, 1971). Little research was done on the disease until the 1990’s due to the rarity of the disease, causing it to be frequently diagnosed erroneously in patients with some of the features such as alopecia and skin of aged appearance (DeBusk, 1972). However, there are three features present in early life; mid-facial cyanosis, skin resembling scleroderma, and glyphic nasal tip, which all facilitate an early diagnosis of HGPS (DeBusk, 1972).

Epidemiology

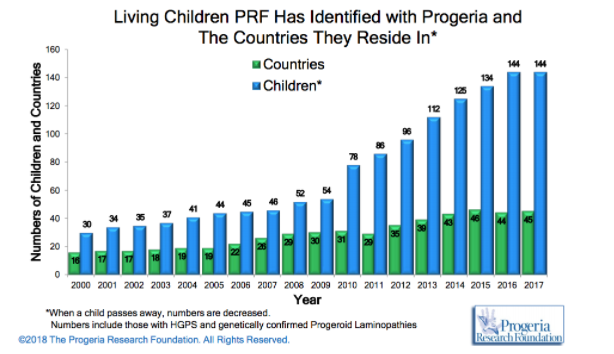

HPGS is an extremely rare genetic disorder affecting about 1 in 4 million live births, if unreported or misdiagnosed cases are taken into account. The reported prevalence rate of the disease is 1 in 8 million births, based on the number of cases (Coppedè, 2013). According to the Progeria Research Foundation database, there are an estimated 350-400 children living with progeria worldwide at any one time. As of January 2018, there are a recorded 114 children living with progeria worldwide with numbers steadily increasing as the years go by (http://www.progeriaresearch.org/prf-by-the-numbersprf.html).

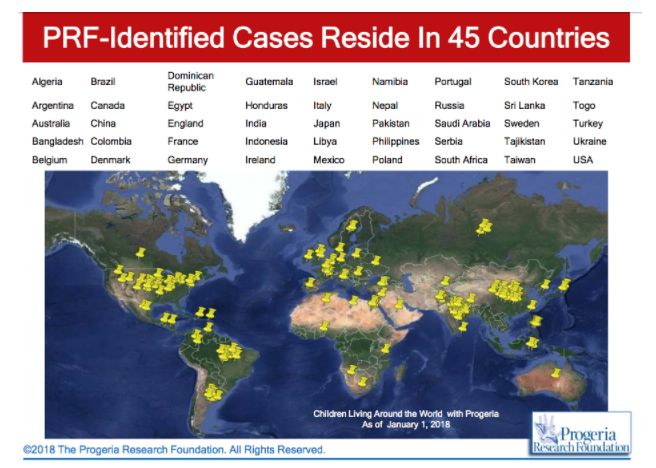

HPGS affects all races; cases of progeria have been discovered in 45 different countries. However, 97% of affected patients are white. Males are affected 1 ½ times more often than females. The disease was thought to be autosomal recessive in the past, however observations made an autosomal recessive inheritance very unlikely and favour a sporadic, dominant mutation. The mutation results in life spans for progeria syndrome to be in the second/third decades of life, with the majority of patients dying of cardiovascular or cerebrovascular disease between 7 and 27 years of age (Sarkar and Shinton, 2001).

Risk Factors

It has been found that there are several risk factors for developing anorexia. These include: perfectionism, negative self-evaluation, obesity, family history of anorexia, affective disorder, substance abuse, obsessive-compulsive disorder and a stress/trigger. It was also found that a lot of these risk factors were correlated to being risk factors of other psychological conditions and that they could have been acquired genetically (Fairburn, Cooper, Doll & Welch, 1999). It should also be mentioned that all of the aforementioned risk factors are not known in detail - their significance is unknown at this point. Social determinants, culture and family also play a role, and vary significantly (“Anorexia Nervosa-What Increases Your Risk”, 2018).

Diagnosis / Symptoms

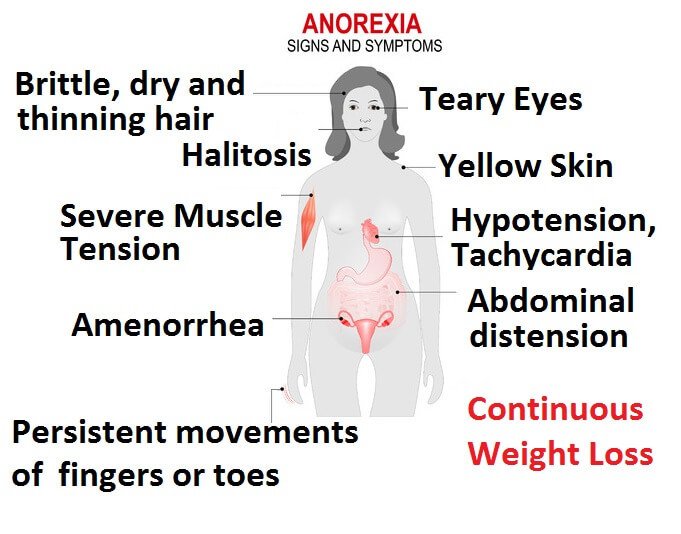

Anorexia is not a straightforward disease to diagnose. It can all be agreed however that a low body weight is the main component for diagnosis. Following such, an individual may also possess fear for gaining weight, as well as have an altered interpretation of healthy weight (Rothenberg, 1988). The first step for diagnosis by the physician is to confirm that the weight loss is not attributed by any other factor. He or she may run several tests to confirm this: a physical exam to determine if the patient’s BMI is under 17.5, and blood tests to measure electrolytes, protein, and thyroid, liver and kidney function. If the tests reveal no abnormalities and the physician believes it is mental, a referral to a mental health professional is commonly seen (“Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa”, 2018). The second step for diagnosis is conducted by a mental health professional, who utilizes the Diagnostic & Statistics of Mental Disorders Manual 5 (DSM-5) as an aid. The professional determines through questionnaires, and evaluations if the patient has fears of gaining weight or has restrictive eating patterns (“Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa”, 2018). Some common symptoms for patients with anorexia are: extreme weight loss, fatigue, insomnia, dizziness or insomnia, constipation and abdominal pain, low blood pressure, and dehydration. Lastly, some patients present with bulimic symptoms - binging and purging (“Anorexia nervosa - Symptoms and causes”, 2018).

Pathophysiology

Biological Effects

Research demonstrates that women with AN will usually overestimate their own body dimensions whereas healthy women will usually tend to underestimate them. The cognitive-affective component of a disturbed body image comprises of negative-body related attitudes and emotions (Vocks et a, 2010). Although it seems that in Western cultures discontent with one’s shape and weight is common those that have eating disorders seem to exceed those of healthy women in terms of body dissatisfaction.

Although AN is characterized as an eating disorder, it remains unknown whether there is a primary disturbance of appetitive pathways, or whether there could be other causes such as anxiety or obsessive preoccupation with weight gain.

Serotonin Function

The 5-HT serotonin system has been studied in individuals that have AN, to suggest that it is possible that this neurotransmitter system plays a role in many symptoms of anorexia such as enhanced satiety, impulse control and mood.

It has been said that these might contribute to an increase in satiety and a more anxious harm-avoidant temperament. Individuals with Anorexia are said to have a reduction in dysphoric mood. Starvation is associated with an increase in postsynaptic 5-HT1A receptor binding potential. Additionally the binding of the 5-HT-2A receptor is positively correlated with harm avoidance in individuals that suffer from AN (Kaye et al, 2009). Individuals with AN will usually pursue starvation ass an attempt to avoid the dysphoric mood that comes as a consequence due to this increased stimulation of postsynaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT2A receptors and therefore makes eating and weight gain aversive (Kaye et al , 2009).

Anterior Insula

The anterior insula is involved in the idea of interoceptive processing which explores the feelings of pain, temperature itch etc. The integration of these internal feelings allows to gain a sense of the physiological condition of the entire body. Altered insula activity supports the idea that individuals with AN have an altered sense of self. As mentioned those that have anorexia experience a strong conflict between the biological need for food and an acquired aversive association with the food. Individuals do not recognize the symptoms of malnutrition, so they do not respond to hunger and they do not have the motivation to change. This is all due the idea of disturbed interoceptive awareness (Kaye et al, 2009).

Individuals who have AN will usually experience an aversive visceral sensation when they are exposed to food or a form of food-related stimuli. This creates a bias towards the reward-related properties of food and creates a more negative emotion. This minimizes the exposure to food stimuli (Kaye et a, 2009).

Current Treatments

Unfortunately today there are no treatments for Progeria. Physicians and healthcare providers’ main goals right now are to delay or reduce symptoms. This can be achieved by: small doses of aspirin, preventative medications, physical and occupational therapy, nutrition and dental care. Common with Progeria, small doses of Aspirin attempt to reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes. Preventative medications that can help lower cholesterol, blood pressure, and reduce the chance of getting a blood clot can all be prescribed if the individual seems to be at risk. Physical and occupational therapy can help an individual maintain healthy movement capability and nutrition and dental care for being overall healthy (Mayo Clinic, 2018). Progeria is commonly screened phenotypically or through medical history at the physician’s office. A genetic test for the LMNA mutations can be ordered if the physician deems this appropriate (Sinha, Raghunath & Ghosh, 2018).

For potential future treatments, there are many different angles of approach. Genetics currently is a big area of research for this disease. Anything from early detection capability, to actual cures, genetics is a significant field to target. Additionally, there is also a lot of interest in reducing the severity of symptoms, common with individuals with Progeria. First, heart and blood vessel disease is a target of interest. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs), which are drugs for treating cancer, are being investigated to whether they can help vasodilate blood vessels and reduce weight gain (Mayo Clinic, 2018). In 2012, 25 children with Progeria underwent a clinical trial that showed these results (Gordon et al., 2012). FTIs also have shown in mouse models to improve nuclear shape and reduce the negative effects of built up prelamin A. Lonafarnib, an FTI, certainly gives confidence for developing a potential cure to Progeria (Sinha, Raghunath & Ghosh, 2018). (a is Progerin cell, d is a healthy cell - treated with FTI - Capell reference)

Conclusion

The causes of anorexia nervosa are not completely understood by medical and psychological professionals, it is acknowledged that an array of biological, social, genetic, and psychological factors play a role in increasing the risk of its onset. The societies we live in have strong beliefs and attitudes toward just about everything. Different groups within a given society adapt these beliefs, attitudes and behaviours altering our beliefs and attitudes toward ourselves and our bodies. Our feelings and behaviour also affect our physical make-up and health. The first step in the recovery process is realizing that our food- and weight-related behaviours are hurting us, rather than helping us. Once an individual is able to realize this, help can be found or offered in a variety of days. Family members and friends may also benefit from information and help. It is possible to prevent the development of food and weight fixation and eating disorders. It is also possible to prevent existing eating disorders from getting worse. It begins with learning and improving our own self-esteem and body image, to working with others and making positive societal changes.

References

Anorexia nervosa - Symptoms and causes. (2018). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 26 March 2018, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anorexia/symptoms-causes/syc-20353591

Diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. (2018). Healthdirect.gov.au. Retrieved 26 March 2018, from https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/diagnosis-of-anorexia-nervosa

Rothenberg, A. (1988). Differential diagnosis of anorexia nervosa and depressive illness: A review of 11 studies. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 29(4), 427-432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0010-440x(88)90024-7

Anorexia Nervosa-What Increases Your Risk. (2018). WebMD. Retrieved 26 March 2018, from https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/eating-disorders/anorexia-nervosa/anorexia-nervosa-what-increases-your-risk

Fairburn, C., Cooper, Z., Doll, H., & Welch, S. (1999). Risk Factors for Anorexia Nervosa. Archives Of General Psychiatry, 56(5), 468. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.56.5.468

Micali, N., Hagberg, K. W., Petersen, I., & Treasure, J. L. (2013). The incidence of eating disorders in the UK in 2000–2009: findings from the General Practice Research Database. BMJ Open, 3(5).

Dell’Osso, L., Abelli, M., Carpita, B., Pini, S., Castellini, G., Carmassi, C., & Ricca, V. (2016). Historical evolution of the concept of anorexia nervosa and relationships with orthorexia nervosa, autism, and obsessive–compulsive spectrum. Neuropsychiatric disease and treatment,12, 1651.

Keski-Rahkonen, A., Hoek, H. W., Susser, E. S., Linna, M. S., Sihvola, E., Raevuori, A., … & Rissanen, A. (2007). Epidemiology and course of anorexia nervosa in the community. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(8), 1259-1265.

Statistics | National Eating Disorder Information Centre (NEDIC). (2018). Nedic.ca. Retrieved 24 March 2018, from http://nedic.ca/node/24