Table of Contents

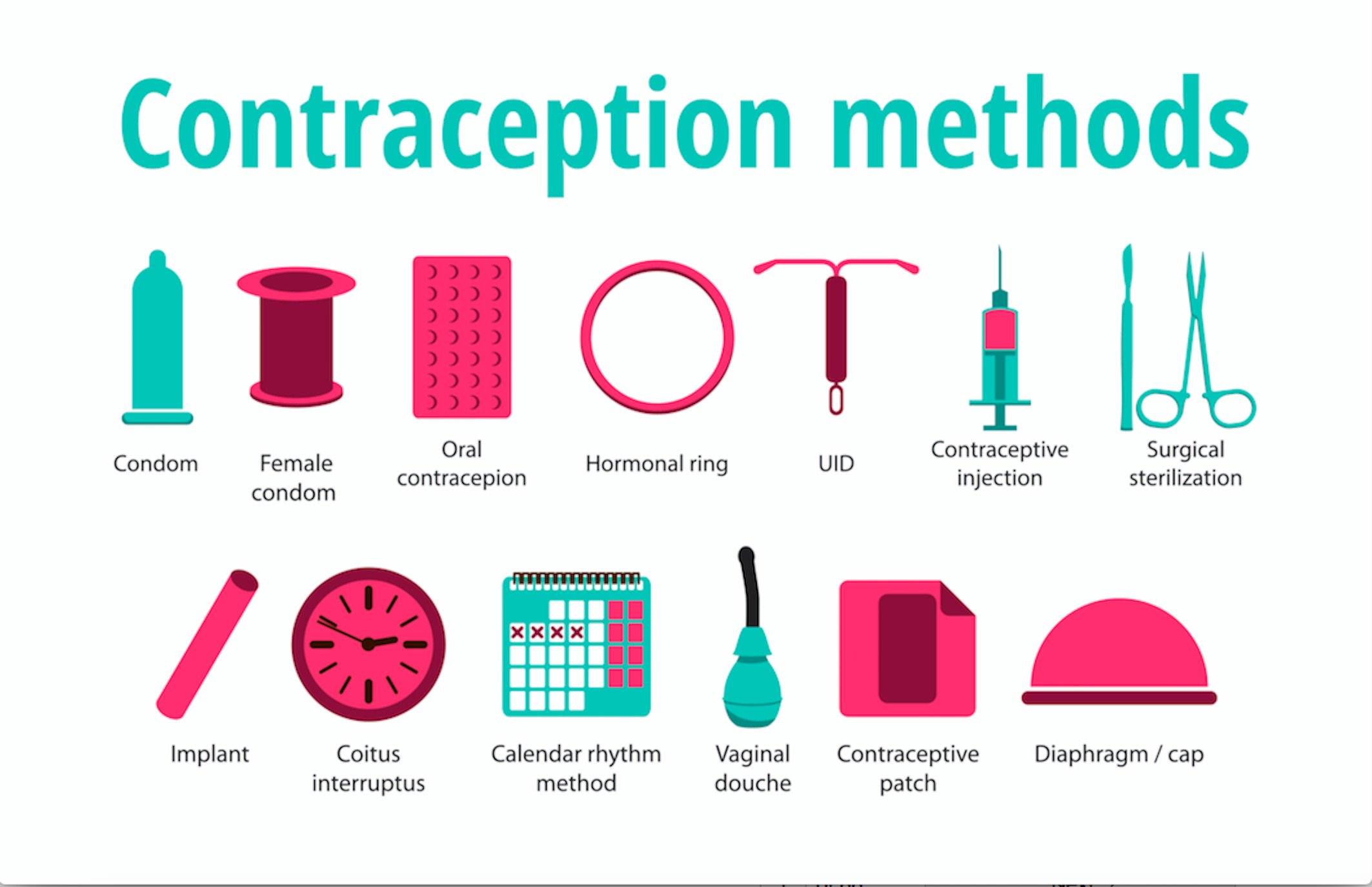

Contraception

What is Contraception/ Birth Control?

Contraception or Birth Control is described as any method, medicine or device used to prevent pregnancy(Office on Women's Health, 2019).

Broad Categories of Birth Control

Long-Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC)

Long- Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) prevents pregnancy for a long period of time effectively. This type of contraception is a reversible method which can be removed to be fertile again. It is one of the most effective methods of contraception. An example of Long-Acting reversible contraception would be an intrauterine device (HealthLinkBC, 2019).

Hormonal Method

Hormonal method prevents eggs from being released from the ovaries by manipulating the hormonal mechanism of the female reproductive system. Hormones from the contraception also thickens the cervical mucus to prevent sperm from entering the uterus and prevent implantation. Examples of hormonal method would be birth control pill/ oral contraceptives and patch (HealthLinkBC, 2019).

Barrier Method

Barrier method prevents the sperm from entering the uterus and reaching the egg. This type of method tends to be unreliable. For example, male condom statistically has 18% failure rate the first year of use. However, barrier method has fewer side effects than the hormonal methods or long acting reversible methods. Examples of barrier method will be male condom, female condom and diaphragm (HealthLinkBC, 2019).

Natural Family Planning

Natural family planning is considered to be one of the most unreliable methods of contraception. Natural family planning is avoiding sex until several days after she has ovulated. This method is developed under the circumstance that the human egg is typically fertile for only 12 to 24 hours after ovulation (HealthLinkBC, 2019).

Permanent Birth Control

Permanent birth control is a lasting protection against pregnancy for both male and female. This permanent birth control method is irreversible method. The surgical process for male is vasectomy. The surgical process for female is tubal ligation. This particular method is recommended when children are no longer in demand (HealthLinkBC, 2019).

Emergency Contraception

Emergency Contraception is a way to prevent pregnancy after unprotected sex. Emergency contraception is more effective within 120 hours of unprotected sex. The mechanism of this type of contraception is not fully understood. Examples of emergency contraception would be Plan B and Copper intrauterine device (HealthLinkBC, 2019).

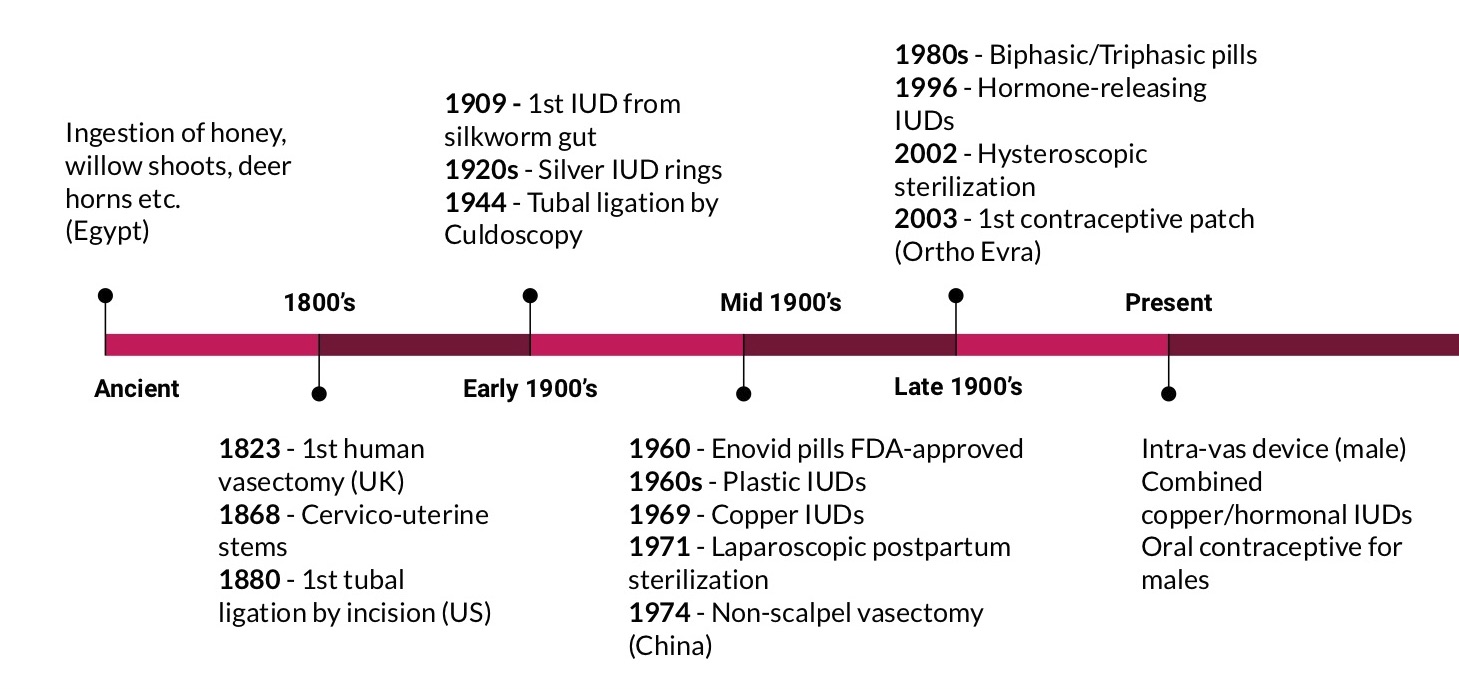

Timeline of Contraceptives

Sterilization for Males

The sterilization technique for males, vasectomy, prevents pregnancy by cutting and sealing up the vas deferens to block the release of spermatocytes from the testes. Males who have undergone vasectomy still produce spermatocytes, but instead of reaching the seminal vesicle to blend in with semen, the cells are trapped within the testes and epididymis, eventually degenerating and being absorbed by the body (WebMD, 2019).

The first case of vasectomy ever recorded in history was performed by British surgeon Astley Cooper in 1823. Interestingly, it was performed on a dog rather than a human for research purposes (Beatty, 2019). Later that year, the first human vasectomy procedure was performed by a Dr Harrison in London; again, it was not used for sterilization, but rather for research on prostatic atrophy (FPA, 2010). From then onwards, vasectomy as a contraceptive measure was gradually developed and introduced into clinical settings.

By the early 20th century, the US became the first country in the world to legalize male sterilization for eugenic purposes, or in other words, for producing better “quality” offspring by selective reproduction (FPA, 2010). In 1954, India became the first to approve vasectomy as a contraceptive program on a national scale. Chinese surgeons further refined the technique by introducing non-scalpel vasectomy in 1974, which enabled surgeons to reach the vas deferens through a tiny puncture rather than an incision (Beatty, 2019). Further improvements continue to be made, with reversible inhibition through the implantation of an intra-vas device being currently explored as an option (FPA, 2010).

Sterilization for Females

Sterilization for females is achieved by cutting and cauterizing the fallopian tubes to obstruct the release of oocytes from the ovaries (Mayo Clinic, 2019). Compared to vasectomy in males, tubal ligation often entails a series of safety concerns as it involves abdominal surgery and requires at least days of hospitalization for recovery (Leuking, 2013).

The female sterilization technique was first proposed by British physician James Blundell in 1834; however, it was not put into practice until US surgeon Samuel Lungren performed the first procedure ever to be published in 1880 (Leuking, 2013). Multiple incisions were required at the time to reach the fallopian tubes, making the procedure rather invasive and difficult to recover from. In 1934, Dr Albert Decker was the first person to apply culdoscopy to the procedure (FPA, 2010). Instead of relying on abdominal incisions to locate the fallopian tubes, culdoscopy only requires a minor incision to be made on the posterior vaginal wall, through which a culdoscope, or specialized endoscope, is inserted into the peritoneal cavity to reach the surgical target (EngenderHealth, 2002). This was a remarkable development as it transformed tubal ligation from a risky surgical operation to a minimally invasive sterilization technique.

In 1971, laparoscopic sterilization was first performed postpartum, with the use of multiple rings and clips to effectively occlude the fallopian tubes (Leuking, 2013). Hysteroscopic sterilization, a non-scalpel technique that utilizes tiny intra-tubal devices, became available in 2002. The intra-tubal devices are designed to be placed at the point of connection between the uterus and fallopian tubes, after being carefully inserted through the vagina and cervix. In spite of its minimally invasive nature, hysteroscopic sterilization is shown to be less effective than other variations to the procedure and thus has not been made widely available (FPA, 2010).

Types of Contraceptions

Non Hormonal Contraception

Sterilization

Vasectomy

A vasectomy is a procedure that is performed to achieve sterilization in males.

Procedure

A vasectomy can be done using two techniques: conventional or non-scalpel. For a conventional vasectomy, an incision is made on the scrotum in order to identify the vas deferens tubes. A portion of the tube is removed followed by the searing (burning) or tying using stitches on the two ends of the tube. With a portion of the tubes removed, sperm cannot be transported to the semen and cannot leave the body. For a non-scalpel vasectomy, the vas deferens tubes are felt under the scrotum and clamped in place by the surgeon. A tiny hole is then made in the skin of the scrotum followed by the stretching of the skin to lift the vas deferens tube out. A portion of the tubes are then removed followed by the searing or stitching of the two remaining ends. A non-scalpel vasectomy is therefore a less invasive procedure than the conventional vasectomy as it does not involve any incisions (Vasectomy Procedure: Effectiveness, Recovery, Side Effects, Pros & Cons, n.d.).

Cost of Contraception

A vasectomy can range from $0 to $1000 based on location, however, it is covered by medical insurance also known as OHIP (Where Can I Buy a Vasectomy & How Much Will It Cost?, n.d.).

Efficacy

Vasectomy is nearly 100% effective (What is the Effectiveness of a Vasectomy?, n.d.).

Side Effects

A vasectomy is a very safe procedure with minimal side effects. However, possible side effects include: swelling and bruising of the scrotum, discomfort or pain, inflammation or infection (Vasectomy Procedure: Effectiveness, Recovery, Side Effects, Pros & Cons, n.d.).

Tubal Ligation

Tubal ligation is a procedure that is performed to achieve female sterilization.

Procedure

Tubal ligation begins with one or two incisions made on the abdomen. A laparoscope, which resembles a small telescope on a flexible tube, is inserted through the incision and is thread towards the fallopian tubes. Once the laparoscope reaches the fallopian tubes, the tubes can either be electrocoagulated (electrocuted), cauterized (seared/burned) or obstructed using a small clip (Tubal Ligation Side Effects, Recovery & Steps in the Procedure, n.d.).

Cost of Contraception

Tubal ligation costs between $0 to $6000 depending on location (How Do I Get a Tubal Ligation & How Much Will It Cost?, n.d.).

Efficacy

Tubal ligation is over 99% effective (How Do I Get a Tubal Ligation & How Much Will It Cost?, n.d.).

Side Effects

Possible side effects include: discomfort at the incision site, abdominal pain or cramping, fatigue, dizziness, shoulder pain, gassiness and bloating (Tubal ligation—Mayo Clinic, n.d.).

Copper IUD

Copper IUDs are sold as Paragard IUD in Canada. They can last between 5-10 years. This works as a spermicide therefore making it difficult for the sperm to reach the egg, resulting in no fertilization leading to no pregnancy. Copper IUD also thins uterus lining to make it unable to support a fertilized egg. They can also slow the transport of egg to delay the chance of sperm and egg meeting. Copper IUDs can also be used as emergency contraception if it is inserted in up to 5 days after unprotected sex (Miller, 2020).

Procedure

Copper IUD is a small device with a fine copper wire wrapped around a plastic frame. This is placed in the uterus. A fine nylon thread is attached to the IUD; the thread comes out the through the cervix into the top end of the vagina (“Copper IUD – Planned Parenthood Toronto”, 2020).

Cost of Contraception

Copper IUD costs about $80- $160 CAD (Miller, 2020).

Efficacy

There is a 99.2% efficacy rate with Copper IUD (“Non-Hormonal IUDs”, 2020).

Side Effects

Some side effects of the Copper IUD include uncomfortable insertion, no protection against STIs, irregular spot bleeding for the first few months and potentially a small chance of infection or perforation (damage to uterus wall) when the IUD is inserted (“Non-Hormonal IUDs”, 2020).

Hormonal Contraception

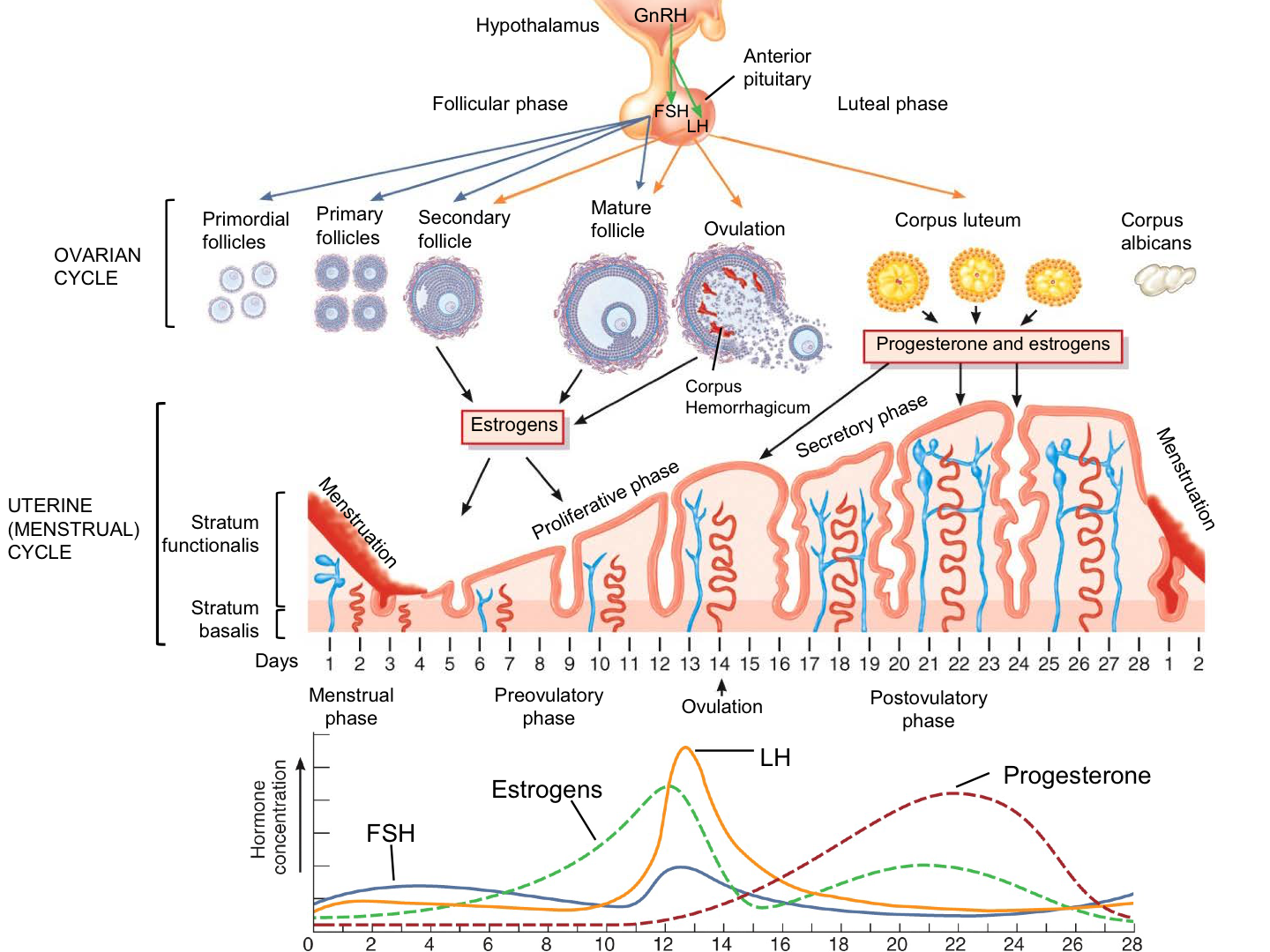

The Menstrual Cycle

Figure 3: Representation of menstrual cycle and hormonal regulation at different stages of menstrual cycle (Tortora et al., 2014)

Figure 3: Representation of menstrual cycle and hormonal regulation at different stages of menstrual cycle (Tortora et al., 2014)

There are 4 major hormones, which to understand the mechanism of the menstrual cycle.

- Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH)- initiates the growth of the follicle (Women In Balance Institute, n.d.)

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH)- causes the release of the eggs from the follicle (Women In Balance Institute, n.d.)

- Estrogen - negatively regulates Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) and positively regulates the luteinizing hormone(LH). Due to positive regulatory system with LH, estrogen creates the surge of LH at mid-cycle.(Women In Balance Institute, n.d.)

- Progesterone - prepares the uterus for implantation/ pregnancy. Progesterone thickens the cervical mucus and changes the endometrium.(Women In Balance Institute, n.d.)

Typically women's menstrual cycle last around 24 days to 35 days with the average of 28 days. Menstrual cycle starts on day 1 of bleeding, as known as period. At the start of menstrual cycle estrogen and progesterone levels are kept low with elevated Follicle Stimulating Hormone(FSH). With this elevated level of FSH the follicle starts to grow. As follicle grows, follicle produces estrogen throughout the body. This then triggers the pituitary gland to produce more Luteinizing Hormone (Women In Balance Institute, n.d.).

At ovulation, around day 12-14 of the menstrual cycle, estrogen level peeks with Luteinizing Hormone. For the Luteinizing Hormone to peak, estrogen levels must be greater than 200pg/mL for approximately 50 hours.(Reed,2018) Then, peak of Luteinizing Hormone causes the release of the dominant follicle (egg) called ovulation. This process of ovulation occurs approximately 10-12 hours after the peak of LH (Reed,2018).

After ovulation had occur, the remaining follicles are now called the corpus luteum. As corpus luteum is created, progesterone level increases. Progesterone thickens the cervical mucus and changes the endometrium. These processes are for the body to prepare the egg for implantation and pregnancy (Reed,2018).

Finally, if the implantation did not occur, corpus luteum breaks down (Fish,2019). This also lowers the progesterone levels in the body, which initiates menstruation (Fish,2019).

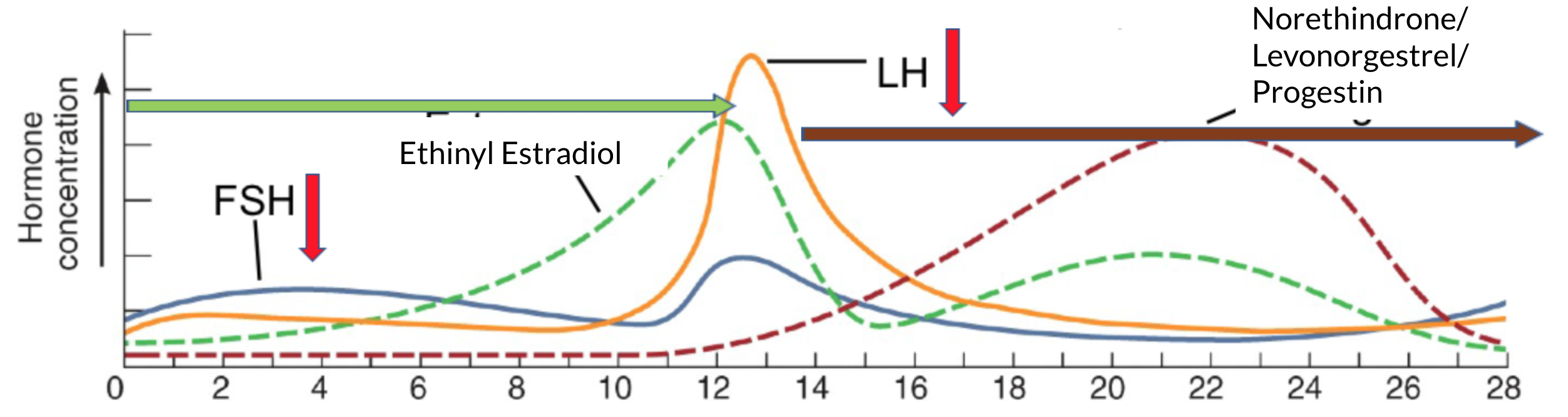

Mechanism of Hormonal Contraceptives

Figure 4: Representation of changes in hormone levels due to the application of hormonal contraception

Figure 4: Representation of changes in hormone levels due to the application of hormonal contraception

Many believe that hormonal contraceptive is “tricking the body into thinking that it's pregnant.” This is because hormonal contraceptives keeps the hormonal level at an elevated level, like pregnant women. The hormonal contraceptives' primary goal is to prevent ovulation. Hormonal contraceptives usually consists of Ethinyl Estradiol(synthetic estrogen) and Norethindrone or Levonorgestrel/Progestin(synthetic progesterone)(Berg,2018).

As mentioned above, estrogen negatively regulates Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH). With external synthetic estrogen, Ethinyl Estradiol, estrogen level is kept constant at an elevated level (Frye,2006). This mechanism will then inhibit the production of the FSH. Inhibition of FSH production will inhibit the growth of follicles. Due to constant level of estrogen, this will inhibit Luteinizing Hormones to peak(Frye,2006). If the Luteinizing Hormones do not peak, this will inhibit ovulation. If the ovulation do not occur, there is no egg for the sperm to fertilize(Frye,2006).

Progestin (synthetic progesterone) also plays an important role in preventing pregnancy. Progestin thickens the cervical mucus (Frye,2006). This makes the uterus to be very dry, an environment unfavourable for the sperm. Thickening of the cervical mucus decreases the probability of the sperm to reach the egg. Additionally, progestin changes the endometrium to affect the survival of a blastocyst within the uterus (Frye,2006).

Different Kind of Hormonal Contraception

Intrauterine Device

Hormonal IUD is sold as Mirena, Kyleena, Liletta or Skyla in Canada. They release progestin, a synthetic version of progesterone hormone. This thickens cervix mucus making it difficult for the sperm to reach the egg. It also thins the lining of uterus so in the rare event the sperm travels to the egg, the thin lining make it difficult for an egg to implant in the uterus and result in pregnancy (“Mirena (hormonal IUD) - Mayo Clinic”, 2020).

Cost of Contraception

Hormonal IUDs costs about $325 - $360 depending on the brand (“Birth Control: 8 Things You Should Know About IUDs”, 2020).

Efficacy

Hormonal IUD's are 99.8% efficient (“Mirena (hormonal IUD) - Mayo Clinic”, 2020).

Side Effects

Hormonal IUD can cause irregular and unpredictable bleeding for up to first 6 months of use, mood changes, acne and depression (“IUD Birth Control | Info About Mirena & Paragard IUDs”, 2020).

Patch

The first contraception patch (transdermal delivery system) was developed in the 1980s. It was a scopolamine patch. As medications have been improved over the years, more transdermal forms were developed. For example, the patch contains nicotine, estradiol for hormone therapy, fentanyl, clonidine, nitroglycerin, among others. For successful delivery of medication through the transdermal system, research had discovered that the molecule/hormone must be small and lipophilic to permeate through the skin. Estradiol and ethinylestradiol (EE) are ideal molecules as therapeutic levels can be delivered easily. (Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

Some benefits of a transdermal patch in comparison to the oral contraceptive pill are less fluctuation in plasma concentrations of estrogen, decrease estrogen-related side effects, and nausea. Also, the users only have to change the patch once every week, as opposed to taking pill daily, which could improve the patient’s adherence. The patch perfect use ranging from 88% to 91% which is higher than the oral perfect use ranged from 68% to 85%. (Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

Pharmacology and pharmacodynamics

Ortho Evra Contraceptive patch is 20cm^2 adhesive patch that releases 35 µg EE and 150 µg norelgestromin (NGMN) per day. NGMN is an active metabolite of norgestimate, the progestin contained in the oral contraceptives Ortho-Cyclen® and Ortho Tri-Cyclen. Three patch sizes are available, 10, 15, and 20 cm2. (Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

Serum levels of NGMN and EE in human body were found to be 20% less if worn on the abdomen compared with the buttock, thigh, or upper arm. However, at all sites, the concentration of NGMN and EE remained within the reference ranges. They also remained within the reference range in conditions of heat, humidity, exercise, and cool-water immersion. (Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

The mechanism of action of NGMN and EE involves 1. thickening the cervical mucus to block or trap sperm 2. decreasing the endometrial receptivity to reduce the chance of implantation 3. inhibiting ovulation by suppressing gonadotropins, FSH and LH. (Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

Steady state concentration is reached within 2 weeks of patch use and the effect of pregnancy prevention is achieved after 1 week. The half-lives of NGMN and EE inside human body are found to be 28.4 and 15.2 hours, respectively. The mean FSH, LH, and estradiol values return to baseline levels 6 weeks after discontinuation. (Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

Cost of Contraception

The cost of the patch can range from free to around $85 a month

Efficacy

In a large trial conducted in the UK, patients taking Evra™ had an incidence of 0.34 unintended pregnancies per 100 women-years. The founding was higher than the rate with second-generation oral contraceptives of 0.16 and 0.12 for third-generation oral contraceptives, but lower than progestin-only oral contraceptives pills at 0.43. (Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

Side Effects

There is relatively higher estrogen exposure of the patch (60% greater AUC) compared to oral contraceptives. This could translate to an increased risk of VTE events compared to women using pills. (Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

The study showed that the overall incidence rate for VTE of 52.8 per 100,000 women-years in patch users and 41.8 per 100,000 women-years in oral contraceptive users. (Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

New Patches

(According to the study from Galzote, Rafie, Teal, & Mody, 2017)

EE/GSD

- The patch contains 0.5mg EE, 2.1mg gestodene

- The dosing of this 11 cm2 patch have the same amount of hormone exposure as the 0.02 mg EE and 0.06 mg GSD oral contraceptive

- It can decrease the EE exposure measured by the AUC compared to the EE/NGMN patch

- The chances of having breast pain was lower in EE/GSD users compared to the traditional EE/NGMN patch users.

EE/LNG

- The patch contains 2.3mg EE, 2.6mg levonorgestrel

- It can decrease the AUC of estrogen and the use of LNG, which can lower the rates of VTE compared to other progestins.

Birth Control Pill/ Oral Contraceptives

Oral contraceptives have been available for more than 50 years and the most commonly used method of reversible contraception (Statistics Canada, 2015). There are two kinds of hormonal contraceptives. Combination hormonal contraceptives, Progestin-only Contraceptives (Sherif,1999).

Combination hormonal contraceptives are the most commonly used oral contraceptives includes both estrogen and progestin. This type of contraceptives can deliver constant or increasing concentration level of progestin/ estrogen throughout the monthly cycle (Sherif,1999).

- Biphasic Combination - two different doses of hormones divided into two phases during the cycle. Constantly low dose of estrogen with escalating progestin level during the cycle (usually escalates during mid-cycle)(Frye,2006).

- Triphasic Combination- three doses in three phases during the cycle. Estrogen levels are low in the beginning of the cycle. Estrogen levels may increase at mid-cycle or remain constant. Progestin levels increases (Frye,2006).

Progestin-Only Contraceptives invented due many side effects that estrogen creates to the body. Serious adverse effects of oral contraceptives are related with high doses of estrogen. In comparison to combination hormonal contraceptives, Progestin-Only contraceptives are slightly less effective (Frye,2006).

Oral contraceptives can be prescribed or can be easily purchase in nearby drug store. Oral contraceptives come in pack of 21, 28, 91 tablets (PlannedParenthood, n.d.).

- 21 tablet packet- take 1 tablet daily for 21 days and then none for 7 days (PlannedParenthood, n.d.)

- 28 tablet packet- 1 tablet daily for 28days in a row. Most pills are hormone free pills for 7 days including iron and other supplement (MedlinePlus, 2015)

- 91 days tablet packet- 1 tablet daily for 91 days, packet contain three different kinds of tablet. Order specific(PlannedParenthood, n.d.).

Oral contraceptives have many other non-contraceptive benefits (Statistics Canada,2015)

- Menstrual cycle regulation

- Less dysmenorrhea

- Fewer ovarian cysts

- Decreased menstrual flow

- Decreased risk of endometrial ovarian cancer

Cost of Contraception around 20-30 dollars per month depending on the health coverage (PlannedParenthood n.d.).

Efficacy clinically the theoretical lowest failure rate of oral contraceptives is <2%. Typically the failure rate of oral contraception is <3% to 5% (Sherif, 1999). Progestin-Only oral contraceptives failure rate is around 3 pregnancies per 100 women per year (Baird & Glasier, 1993).

Side Effects of Oral contraceptives are as follow

- Nausea/ headaches

- Vomiting

- Stomach Cramp or bloating

- Diarrhea

- Increased or decreased appetite

- Weight gain or loss

- Change in menstrual flow

- Breast Tenderness (enlargement or discharge)

- Acne

- Risk of cardiovascular events (specifically Venous Thromboembolism)

Some side effects of oral contraceptives like nausea and headaches can be caused due to estrogen. Estrogen is a vasodilators which can cause migraines and headaches. Progestin can cause the smooth muscle relaxation which can cause the gastroesophageal reflux (Sherif,1999).

Oral Contraceptives are known to increase the chance of cardiovascular events like venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction and stroke. Among the long term oral contraceptives users, risk of venous thromboembolism is two times higher. This is associated with estrogen component of the oral contraceptives. Estrogen receptors in the liver are involved in producing the blood clotting factors (Berg,2015). Furthermore, the synthetic estrogen, ethinyl estradiol, is much more attracted to the estrogen receptor in the liver. Therefore, ethinyl estradiol hyper-activates the liver pathway to create blot clotting factor. This will place the oral contraceptive users to be more prone to Venous Thromboembolism (Berg,2015).

Male Contraception

More than 25% of couples worldwide use a male method of contraception (condoms and vasectomy). Meanwhile, reversible female hormonal contraceptive options have been exponentially growing over last decade. Such as, oral contraceptives, patches and intrauterine devices. For male, left them with no option but condom with the failure rate of 18% in the first year of use and vasectomy which is irreversible. After 400 years of no new reversible male contraceptive option, there seems to be hope for new male hormonal contraceptives.

Mechanism

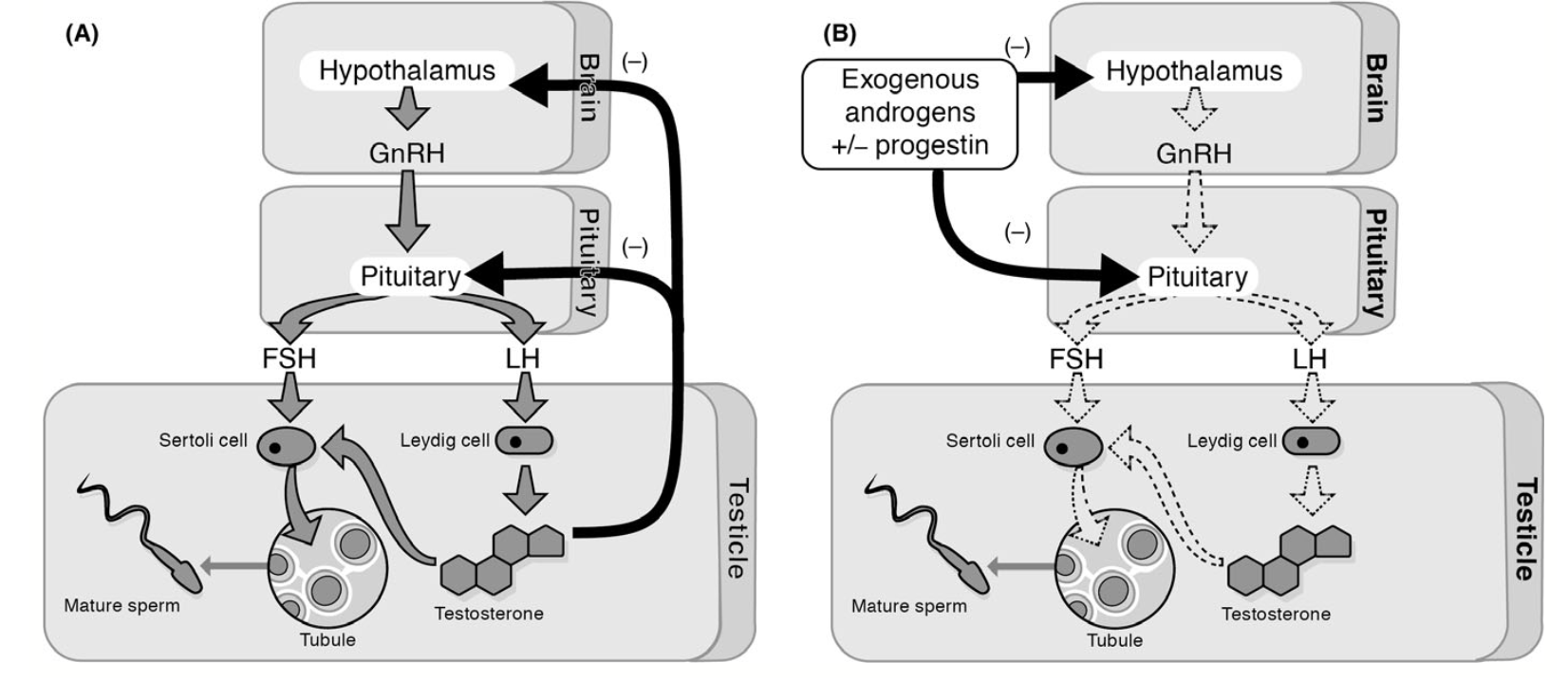

Figure 5: Diagram A. shows the normal hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal feedback loop. Diagram B. shows the hormonal regulated hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal feedback loop regulated by potential male hormonal contraceptive (Roth et al,. 2015)

Figure 5: Diagram A. shows the normal hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal feedback loop. Diagram B. shows the hormonal regulated hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal feedback loop regulated by potential male hormonal contraceptive (Roth et al,. 2015)

Similar to female hormonal contraceptives, the male hormonal contraceptive targets the normal hypothalamic- pituitary gonadal feedback loop. In male, the feedback loop initiates the steroidogenesis and spermatogenesis (Roth & Amory 2016). In a normal man, hypothalamus releases gonadotropin releasing hormone which stimulates the Luteinizing Hormone (LH) and Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH) from the pituitary. Then LH binds to androgen receptor to initiate the steroidogenesis, releasing testosterone (Roth & Amory 2016). The other hormone FSH binds to the Sertoli cells to stimulate spermatogenesis. After testosterone level is elevated, testosterone diffuses out of the testes and inhibits hypothalamus and pituitary gland for further production of FSH and LH (Roth & Amory 2016).

As for male hormonal contraception, it aims the male to become azoospermia (Roth & Amory 2016). Azoospermia means to lack of any measurable sperm in the ejaculation. However, due to so many variations in the male body azoospermia is nearly impossible. Therefore, the male hormonal contraceptives aim for a severe oligozoospermia (Roth & Amory 2016). In male semen, usually there are 15 million sperm/ml. However, in case of severe oligozoospermia, there are about 1million sperm/ml. With oligozoospermia, the pregnancy rate is 1% per year, which is considerable to be effective as contraceptive (Roth & Amory 2016). Essentially, male hormonal contraceptive mechanism is suppressing the hypothalamic- pituitary gonadal feedback loop by adding external androgen or progestin. By regulating this feedback loop, this mechanism will suppress the production of both FSH and LH. With the inhibition of FSH and LH production, there is a decrease in spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis. As a result, there will be a substantial decrease in sperm count (Roth & Amory 2016).

Three Clinical Trials

Nestorone and Testosterone

- 19-Norprogesterone- derived from progestin with no androgenic, estrogenic activity

- Applied as a daily transdermal gel

- Show effective suppression of gonadotropin when used for 20 days

- Studied in 6month trial and 89% percent of men achieved suppression of sperm

Dimethandrolone Undecanoate (DMAU)

- Synthetic 19-norandrogen that is hydrolyzed into dimethandrolone in vivo

- Act as both androgen and progesterone receptors

- No significant side effects on metabolic outcomes or bones

- Reversible suppression found in animal studies in rodents and rabbits

- Phase 1 testing conducted with short term safety and tolerability with reversible suppression

- Applied by injection or orally

7- Alpha- Methyl- 19 – Nortestosterone

- Synthetic androgen with no activity at progesterone receptor

- Developed as an implant for long-term hormonal contraception

- Much higher binding activity at the androgen receptor than testosterone

- Sustained release of the hormone over an year (Roth & Amory 2016)

Side Effect and Efficacy

Side effects and efficacy cannot be fully determined at the moment. None of the clinical studies have been conducted for more than 2.5 years. Only significant side effects that were determined among the contraception were with testosterone therapy. Testosterone therapy increased in lean body mass and bone mineral density (Roth & Amory 2016).

Among other therapies

- Acne

- Changed in body weight

- Changes in cholesterol profile (decreased HDL, LDL and total cholesterol)

- Mood changes (Roth & Amory 2016)

Conclusion

In conclusion, contraceptives have evolved significantly over the past two centuries. Initially, birth control methods heavily relied on a physical barrier approach to now more sophisticated hormone based techniques. With more research and knowledge, there is an increase in efficacy as well as safety. There is a wide range of options including but not limited to permanent methods, long-term reversible options as well as emergency contraceptions. OHIP in Canada is able to cover some costs for certain contraceptive methods such as most combined birth control pills, emergency IUDs and injections. It can be assured that there is something that works for everyone!

References

Baird, A., & Glasier, A.,(1993). Hormonal Contraception. The New England Journal of Medicine, 328(21). doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305273282108

BC option. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2020, from http://www.ppt.on.ca/facts/bc-options/ Berg, E. G. (2015). The Chemistry of the Pill. ACS Central Science, 1(1), 5–7. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.5b00066

Beatty, D. (2019, January 1). History of Vasectomy. Retrieved January 22, 2020, from https://thevasectomist.com.au/history-of-vasectomy/

Birth Control. (2019, November 5). Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/hw237864

Birth Control: 8 Things You Should Know About IUDs. (2020). Retrieved 31 January 2020, from https://www.besthealthmag.ca/best-you/girlfriends-guide/birth-control-iud/

Copper IUD – Planned Parenthood Toronto. (2020). Retrieved 31 January 2020, from http://www.ppt.on.ca/facts/copper-iud/

Dean, M. (2019, June 28). All Hail Contraceptives! Retrieved January 21, 2020, from https://www.studentpost.org/2017/12/all-hail-contraceptives/

EngenderHealth. (2002). Contraceptive Sterilization: Global Issues and Trends. Retrieved January 21, 2020, from https://www.engenderhealth.org/wp-content/uploads/imports/files/pubs/family-planning/factbook_chapter_6.pdf

Estrogen and Progestin (Oral Contraceptives): MedlinePlus Drug Information. (2015, September 15). Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a601050.html

Fish, S. (2019, October). Progesterone. Retrieved from https://www.hormone.org/your-health-and-hormones/glands-and-hormones-a-to-z/hormones/progesterone

Frye, C. A. (2006). An overview of oral contraceptives: Mechanism of action and clinical use. Neurology, 66(Issue 6, Supplement 3). doi: 10.1212/wnl.66.66_suppl_3.s29

FPA. (2010, November 15). Contraception: past, present and future factsheet. Retrieved from http://www.fpa.org.uk/factsheets/contraception-past-present-future

Galzote, R., Rafie, S., Teal, R., & Mody, S. (2017). Transdermal delivery of combined hormonal contraception: a review of the current literature. International Journal of Womens Health, Volume 9, 315–321. doi: 10.2147/ijwh.s102306 Hormone Imbalance, Menstrual Cycles & Hormone Testing. (n.d.). Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://womeninbalance.org/about-hormone-imbalance/

Glassier, A. (2002, October 1). Contraception: Past and Future. Retrieved January 21, 2020, from https://www.nature.com/fertility/content/full/ncb-nm-fertilitys3.html

How Do I Get a Tubal Ligation & How Much Will It Cost? (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2020, from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control/sterilization/what-are-benefits-sterilization

IUD Birth Control | Info About Mirena & Paragard IUDs. (2020). Retrieved 31 January 2020, from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control/iud

Leuking, A. (2013, March 20). Review of Female Sterilization. Retrieved January 20, 2020, from https://www.wesleyobgyn.com/pdf/lectures/Female-Sterilization.pdf

Miller, K. (2020). 13 Things You Absolutely Should Know Before Getting the Copper IUD. Retrieved 31 January 2020, from https://www.self.com/story/copper-iud-facts

Mirena (hormonal IUD) - Mayo Clinic. (2020). Retrieved 31 January 2020, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/mirena/about/pac-20391354

Nikolchev, A. (2010, May 11). A brief history of the birth control pill. Retrieved January 21, 2020, from https://www.pbs.org/wnet/need-to-know/health/a-brief-history-of-the-birth-control-pill/480/

Non-Hormonal IUDs. (2020). Retrieved 31 January 2020, from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control/iud/non-hormonal-copper-iud

Parenthood, P. (n.d.). How to Use Birth Control Pills: Follow Easy Instructions. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control/birth-control-pill/how-do-i-use-the-birth-control-pill

Reed, B. G. (2018, August 5). The Normal Menstrual Cycle and the Control of Ovulation. Retrieved January 29, 2020, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279054/

Roth, M. Y., Page, S. T., & Bremner, W. J. (2015). Male hormonal contraception: looking back and moving forward. Andrology, 4(1), 4–12. doi: 10.1111/andr.12110

Roth, M., & Amory, J. (2016). Beyond the Condom: Frontiers in Male Contraception. Seminars in Reproductive Medicine, 34(03), 183–190. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1571435

Sherif, K. (1999). Benefits and risks of oral contraceptives. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 180(6). doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70694-0

Statistics Canada. (2015, November 27). Oral contraceptive use among women aged 15 to 49: Results from the Canadian Health Measures Survey. Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2015010/article/14222-eng.htm

Tortora, Gerald, and Bryan Derrickson. “The Menstrual Cycle.” John Wiley & Sons, 2014.

Tubal ligation—Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2020, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/tubal-ligation/about/pac-20388360

Tubal Ligation Side Effects, Recovery & Steps in the Procedure. (n.d.). EMedicineHealth. Retrieved January 31, 2020, from https://www.emedicinehealth.com/tubal_sterilization/article_em.htm

Vasectomy Procedure: Effectiveness, Recovery, Side Effects, Pros & Cons. (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2020, from https://www.webmd.com/sex/birth-control/vasectomy-overview

What birth control method is right for you? (2019, February 14). Retrieved January 27, 2020, from https://www.womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/birth-control-method

What is the Effectiveness of a Vasectomy? (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2020, from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control/vasectomy/how-effective-vasectomy

Where Can I Buy a Vasectomy & How Much Will It Cost? (n.d.). Retrieved January 31, 2020, from https://www.plannedparenthood.org/learn/birth-control/vasectomy/how-do-i-get-vasectomy

Presentation 4m03_topic_1.pdf