This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Obesity

Introduction

Obesity is a progressive illness which is usually defined by an abnormal and excessive accumulation of body fat that can have a negative impact on one’s health (Mokdad et al., 2003).

Obesity is a progressive illness which is usually defined by an abnormal and excessive accumulation of body fat that can have a negative impact on one’s health (Mokdad et al., 2003).

Population health studies estimate the prevalence of obesity by categorizing individuals based on a Body Mass Index (BMI) (Katzmarzyk & Mason, 2006). Generally, individuals with a body mass index greater than 30 kg/m2 are considered to be obese. However, a body mass index alone is not enough to diagnose someone with obesity. A qualified health care professional will make the diagnosis based on additional clinical tests and measures (Katzmarzyk & Mason, 2006).

Studies show that the prevalence of obesity has increased significantly in the last 30 years (“Obesity in Canada,” n.d.). According to the 2014 and 2015 Canadian Community Health Surveys, over 5 million adults have obesity and 30% of adults in Canada have obesity and these individuals may require medical support to manage their condition. Organizations such as Obesity Canada, the American Medical Association and the World Health Organization now consider obesity to be a chronic disease. Furthermore, obesity is the main cause of of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, heart disease, stroke, arthritis and cancer. In fact, 1 in 10 premature deaths among Canadian adults from ages 20 to 64 is thought to occur directly due to obesity related complications (“Obesity in Canada,” n.d.).

In 2001, a US study conducted a telephone survey of 195 005 adults aged 18 years or older residing from all states (Mokdad et al., 2003). They found the prevalence of obesity (BMI ≥30) to be 20.9% and had risen dramatically when compared to prevalence rates from the 1990’s. Overall, the study concludes that increases in obesity among US adults continue in both sexes, all ages, all races, all educational levels, and all smoking levels (Mokdad et al., 2003).

Aside from physiological impairments, obesity can also impact one’s overall psychological, social and economic well-being due to the social stigma associated with the disease. Obesity stigma can cause unequal access to employment, healthcare and education. This is because some individuals may view obese people as lazy, careless and apathetic.

Studies predict that the direct healthcare cost of obesity based on hospitalization and medication costs is approximately $7 billion (“Obesity in Canada,” n.d.). By 2021, the costs are expected to rise to $9 billion and continue to rise as the prevalence of obesity is expected to increase during the next two decades (“Obesity in Canada,” n.d.).

Ultimately, public, private and non-governmental initiatives covering the rises of obesity and treatment options are needed to control this global epidemic.

Diagnosis

Obesity diagnosis can be based on the individual’s physical exam, medical history, their body mass index, and their waist circumference (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019).

Body Mass Index

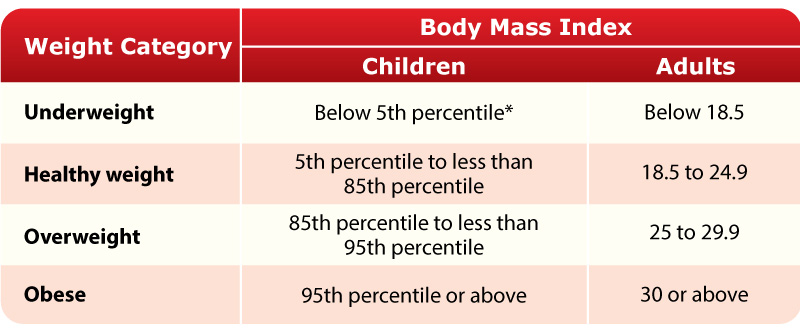

Dependent on if you are a child or adult, doctors use calculations to measure the BMI of the individual to diagnose obesity. The body mass index is a calculation that uses an individual’s weight and height. The formula is BMI = weight (kg) / height (m^2). The body mass index is used to determine whether the individual is underweight, healthy weight, overweight, or obese. Looking at the chart provided, children are considered underweight if their BMI is under the 5th percentile, and adults are considered underweight if their BMI is under 18.5 (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019). Children are considered obese if their BMI is the 95th percentile or above, and adults are considered overweight if their BMI is 30 or above (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019).

Physical and Medical Examination

Doctors tend to ask the individual about their family history and the individual’s physical and eating habits, which helps them to determine whether other conditions are causing obesity or if obesity is causing any other complications (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019). When the doctors are doing a physical exam, the doctor’s look at the abdomen examining the unhealthy fat it contains, which allows them to measure your waist circumference (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019).

Causes

One of the causes of obesity is an imbalance in energy (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019). This energy is calculated in calories and means that the energy going out does not equal the energy coming in. Energy going out is when the body uses the calories for breathing or physical activities. Energy going in is when the body gains the calories from drinks and food. When the body takes in more calories then it uses, that is when obesity develops (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019). The imbalance in energy leads to the body storing fat.

There are many medicines in the market that can lead to an individual gaining weight and becoming obese. Some of these medicines include antipsychotics and antidepressants (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019).

Hormones produced by the endocrine system help maintain a balance in energy in the body. When there is a disorder or tumor in the endocrine system, it can lead to the individual becoming obese (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019). An example of this is hypothyroidism (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019). Individuals that have this condition have a low amount of thyroid hormones. This is linked with reduced metabolism, leading to the individual gaining weight.

Risk

Obesity has many risk factors that can be changed and many risk factors that cannot be changed. The factors that can be changed are environments and unhealthy lifestyle habits (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019). The factors that cannot be changed are age, sex, genetics, family history, and ethnicity (National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, 2019). Changing your unhealthy lifestyle habit into a healthy lifestyle can decrease the risk of becoming obese.

Pathophysiology

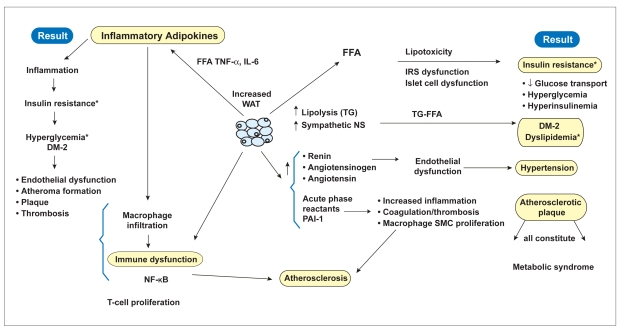

In the past decade, a bulk of research regarding obesity has looked into its regulation since it is tied with molecular regulation of appetite, ultimately affecting energy homeostasis. With that said, during nutrient deprived states, like starvation, a plethora of stored fat is necessary in order for the individual’s survival. On the other hand, during prolonged abundance of food in the body, there is excessive storage of fats that result in obesity, due to the body’s extremely efficiency fat storage system (Spiegelman & Flier, 2001). The excessive storage of fat that creates obesity will stimulate an enhanced sympathetic state, which will eventually lead to release of excessive fatty acids from enhanced lipolysis. Subsequently, this excessive release of fatty acids are free in the body and can stimulate lipotoxicity because there is oxidative stress to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mitochondria of cells that is created by the lipids and their metabolites. Not only does this phenomenon affect adipose tissues, but also non-adipose tissues as well, which is why obesity extends its pathophysiology to many organs like the kidneys, liver and pancreas as well as in metabolic syndrome (Evans, Barish, & Wang, 2004). In addition, fatty free acids that are secreted from excessively stored triglyceride also aid in the inhibition of lipogenesis which prevents proper clearance of serum triglyceride levels. As a result, the improper clearance of triglyceride contributes to hypertriglyceridemia which means there are a high levels of triglycerides on the blood serum. One consequence of hypertriglyceridemia is the release of fatty acids by endothelial lipoprotein lipase within elevated beta lipoproteins. With that said, there is insulin-receptor dysfunction due to this elevation and this dysfunctional state creates hyperglycemia and increased glucose production in the liver. Furthermore, one other effect from the lipotoxicity caused by excessive fatty acids is a decrease in the secretion of insulin from the pancreas, resulting in beta-cell exhaustion (Redinger, 2007).

Linked Diseases

When an individual suffers from obesity, there are many increased health risks for certain diseases, making them more susceptible. These include sleep apnea, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary heart disease, gall stones, cancer, gout and arthritis, to name some. However, the three leading diseases linked to obesity are type 2 diabetes, coronary heart disease and cancer (Redinger, 2007).

Since obesity is accompanied by inflammation in many of the tissues and organs within the body, a major risk factor of obesity includes cancer in various forms like breast, colon, renal and prostate, to name a few. In fact, obesity was found to account for 20 to 33% of breast, esophageal, endothelial and kidney cancer. The increased risk of cancer is brought about through many different mechanisms seen in the pathophysiology of obesity. For instance, the risk of colon cancer is increased due to the combined effects of diabetes, insulin resistance and increased BMI because the excessive fatty acids exert lipotoxicity leading to decreased insulin secretion. Additionally, studies have observed an association between the increased leptin levels that occur in obese individuals and cancer. Thus, cancer risk increased as these leptin levels contribute to cellular proliferation, dedifferentiation and inhibition of apoptosis in cancer (Redinger, 2007).

Another disease that is closely linked to obesity is type 2 diabetes mellitus, due to insulin-receptor dysfunction and beta-cell exhaustion from elevated beta lipoproteins, as well as progressive insulin resistance. Since both insulin resistance and insulin-receptor dysfunction occur early in obese individuals, they progressively worsen overtime which ultimately lead to type 2 diabetes (Golay & Ybarra, 2005). One key factor that contributes to the onset of diabetes and insulin resistance in obese individuals is tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), which is a pro-inflammatory adipokine. With that said, increased secretion of TNF-alpha is observed with higher total body-fat mass individuals and it enhances inflammation in fatty livers and fat depots in other locations of the body, like the pancreas. Through interference with insulin receptor tyrosine kinase activity in both fat and muscle tissues, TNF-alpha causes insulin resistance and dysfunction and abnormalities of the pancreatic insulin receptors, as seen in multiple mice studies. Thus, leading to type 2 diabetes (Hotamisligil & Spiegelman, 1994).

Lastly, individuals whom suffer with obesity are at major risk for development and progression of sleep apnea. In fact, sleep apnea is twice as prevalent in obese adults compared to normal-weight adults. Additionally, within obese children sleep apnea is 6 times as prevalent than in normal-weighted children. The link between obesity and sleep apnea is very complex, however evidence from studies show that there is a correlation that is present. With that said, possibility for obesity to worsen sleep apnea occurs due to fat deposition at specific sites in the body. For instance, there is fat deposition within tissues that surround the upper respiratory tract and trachea which makes an individual more vulnerable to sleep apnea. Moreover, there are also fat deposits around the thorax which reduce chest compliance, increase oxygen demand and reduce the volume of air present in the lungs when exhaling passively (Romero-Corral et al., 2010).

Prevention

In order to prevent obesity, it is important to eat and drink according to nutritional needs, exercise regularly, and monitor weight (Wirth, Wabitsch, & Hauner, 2014). Along with this, it is recommended that individuals consume foods with a low energy density as they often have a high water and fibre content (Wirth et al., 2014). Some examples include foods containing whole grains, fruits, and vegetables. In order to eat healthy, it is also recommended that the consumption of sugary drinks, alcohol, and fast food be reduced as they have a high fat and sugar content (Sayon-Orea, Martinez-Gonzalez, & Bes-Rastrollo, 2011). Other drinks such as fruits juices are also sweetened, high in sugar, and are not filling, which may cause an individual to consume greater quantities (Vartanian, Schwartz, & Brownell, 2007). In addition to consuming nutritious foods, living an active lifestyle can also prevent obesity. Periods of sitting should be reduced and individuals should engage in activities that promote weight loss (Wirth et al., 2014). A study by Donnelly et al. (2009) found that weight loss goals are best accomplished through endurance-focused exercise where large muscle groups are used for over 2 hours per week. With a combination of exercise and monitoring what is consumed, the risk of obesity can be reduced or prevented.

Treatment

Treatment for obesity depends on the individual’s BMI and body fat distribution, an assessment of risk factors, the presence of existing medical conditions, and the patient’s preferences (Wirth et al., 2014). If an individual is seeking treatment, there are often indicators that can assess whether it is needed (Wirth et al., 2014). For one if an individual has a BMI that is equal to, or greater than 30 kg/m2 , then they are considered to be obese. If an individual’s BMI is between 25 and 30 kg/m2, then they are considered to be overweight but treatment would be recommended if this were also accompanied by other factors. These factors include other health impairments related to weight gain such as type 2 diabetes or hypertension, psychosocial stress, and abdominal obesity. More specifically, in seeking treatment, the long-term impacts of cardiovascular risk factors also need to be taken into account (Lawlor & Chaturvedi, 2006). This includes risk factors such as dyslipidaemia, hypertension, and insulin resistance. Along with this, disease outcomes such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and osteoporosis also need to be assessed.

Goals for Treatment

Prior to treatment, it can be beneficial to set goals in order to see desirable outcomes and maintain the results. For example, individuals with a BMI between 25 and 35 kg/m2 should aim to lose over 5% of their initial weight (Wirth et al., 2014). For individuals with a BMI greater than 35 kg/m2, they should aim to lose over 10% of their initial weight. Other goals for treatment should be to decrease the risk factors that can lead to obesity and any diseases associated with it, reduce the risk of early death, prevent early retirement as a result of a decline in health, improve quality of life, and improve psychosocial health (Wirth et al., 2014).

Forms of Treatment

Diets

For diets, recommendations are personal according to the risk profile of the patient and their goals (Wirth et al., 2014). Diet plans are only effective if the patient complies with the lifestyle changes and recommendations. Diet plans can also be offered through diet therapy, where nutritional counselling is often received along with a medical management program. This can occur individually or in groups, but research has shown that group sessions can be more effective (Wirth et al., 2014). Within these sessions, diet recommendations can consist of strategies to reduce fat consumption, carbohydrate consumption or both. Research has looked at many effects of weight loss interventions in adults with obesity (Wirth et al., 2014). It was found that very low energy density diets consisting of less than 800 kcal/day, resulted in weight loss with about 15-25% of initial weight lost over a short period for individuals who completed a program. However, there are downsides to such programs as they can be expensive, and have a high chance of regaining 50% of the lost weight. In addition, there are many programs available over the internet, but it was found that many of these did not show weight loss results (Wirth et al., 2014). Other diets that have shown to be effective are low fat diets. They have positive effects on blood pressure and dyslipidaemia for obese individuals (Lawlor & Chaturvedi, 2006).

Weight Loss Drugs

Weight loss drugs are only recommended for use along with other interventions such as exercise, diet and behavioural therapy. One common type is Orlistat (Wirth et al., 2014). This is a gastrointestinal lipase inhibitor and aids in reducing fat absorption. It is recommended for individuals with a BMI over 28, or if there is a presence of other risk factors or co-morbidities. It can also be used if other basic programs for weight loss have not been effective. GLP-1 mimetics and SGLT2 inhibitors can also be used but are recommended for individuals with a BMI over 30, or if they have type 2 diabetes. GLP-1 regulates insulin and digestion and works to reduce appetite, while SGLT2 reduced glucose levels in the body. Furthermore, drugs such as diuretics, amphetamines, human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG), thyroxine, testosterone, and growth hormones are not recommended because their benefits don’t always outweigh the risks (Wirth et al., 2014).

Physical Exercise

Exercising daily or during free time can decrease risk factors and obesity associated disease while improving weight loss (Lawlor & Chaturvedi, 2006). It is recommended that individuals engage in over 150 minutes of exercise per week along with monitoring their caloric intake for optimal results. Research also shows that strength training alone is not effective, and that working out using large muscle groups, with moderate to high intensity is more beneficial (Wirth et al., 2014). Overall, there is great health value associated with an increase in exercise besides just weight loss as overall health can also be improved.

Behaviour Modification and Behavioural Therapy

This form of treatment works to implement lifestyle changes. This therapy is often a program for weight reduction and can occur in a group setting or individually. It mainly focuses on lifestyle changes such as nutrition and exercise, and methods to improve them (Wirth et al., 2014). In cases where symptoms are more severe such as depression or eating disorders, psychiatrists and psychotherapists could be involved. In this form of treatment, common strategies are used that can be adjusted depending on the individual case and expectations. Some of these strategies consist of:

- Social support

- Observing progress and behaviour (exercise, eating habits, and body weight)

- Controlled, flexible, exercise and eating rather than rigorous control

- Controlling stimuli that may trigger eating

- Strategies to deal with any return of weight gain

- Cognitive reconstruction (modifying thoughts that are dysfunctional)

- Training for problem-solving

- Training for assertiveness or social competence

- Strategies for reinforcement (rewarding any changes that are observed)

- Prevention strategies for relapse

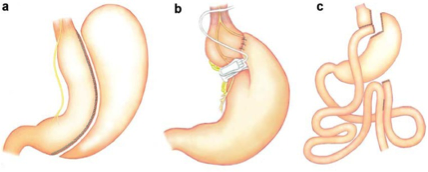

Surgical Interventions

Surgery is often used for cases of extreme obesity or if all other conservative treatment methods are not successful (Wirth et al., 2014). It can also be recommended as a primary treatment before trying conservative methods if it is believed that they will have no effect. Surgery is often used for three different grades of obesity that are characterized by BMI (Wirth et al., 2014). Grade I is for individuals with a BMI between 30 and 35, with type 2 diabetes. Grade II obesity categorizes individuals with a BMI between 35 and 40 with significant co-morbidities, while grade III obesity means the individual has a BMI over 40. Different types of surgery can also be used such as sleeve gastrectomy (a), gastric banding (b), and gastric bypass ©. Overall, surgery is more effective in reducing body fat, decreasing obesity related disease, and decreasing mortality risk due to the large impact it can have compared to other treatments (Lawlor & Chaturvedi, 2006). To put this into perspective, one study found that in a one to two year time span, individuals were able to lose 20-40kg through bariatric surgery, 4-6kg through dietary therapy, and only 2-3 by exercise therapy (Lawlor & Chaturvedi, 2006). However, these results would vary depending on the individual, their dedication, and maintenance of their health goals.

Conclusion

Obesity is a problem that is impacting many individuals around the world specifically in western countries. This disease can be inherited by environmental or genetic factors. With the consumption of many fats, and high caloric meals the individual can develop obesity. It is critical that the individual burns more calories than they consume. Although, this may not always be the reason but, research has shown that if a person has low to none exercise levels, he or she has a high possibility to develop obesity. Medicines such as insulin and thiazolidinediones (TZDs) can also result in excessive weight gain (OAC, n.d.). Using the body mass index, we can determine whether the person is obese or not. If the child is 95th percentile or over they are considered to be obese and if the adult is 30 or above he/she is obese. To prevent obesity from happening it is critical that to maintain a healthy lifestyle and ask doctors about what medication can result in weight gain.

References

Donnelly, J. E., Blair, S. N., Jakicic, J. M., Manore, M. M., Rankin, J. W., & Smith, B. K. (2009). Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 41(2), 459-471.

Evans, R. M., Barish, G. D., & Wang, Y.-X. (2004). PPARs and the complex journey to obesity. Nature Medicine, 10(4), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm1025

Golay, A., & Ybarra, J. (2005). Link between obesity and type 2 diabetes. Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 19(4), 649–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beem.2005.07.010

Hotamisligil, G. S., & Spiegelman, B. M. (1994). Tumor necrosis factor alpha: a key component of the obesity-diabetes link. Diabetes, 43(11), 1271–1278.

Katzmarzyk, P. T., & Mason, C. (2006). Prevalence of class I, II and III obesity in Canada. CMAJ : Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de l’Association Medicale Canadienne, 174(2), 156–7. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.050806

Lawlor, D. A., & Chaturvedi, N. (2006). Treatment and prevention of obesity—are there critical periods for intervention?.

Mokdad, A. H., Ford, E. S., Bowman, B. A., Dietz, W. H., Vinicor, F., Bales, V. S., & Marks, J. S. (2003). Prevalence of Obesity, Diabetes, and Obesity-Related Health Risk Factors, 2001. JAMA, 289(1), 76–79. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.1.76

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. (2019). Overweight and Obesity. [online] Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/overweight-and-obesity [Accessed 31 Mar. 2019].

Obesity in Canada - Obesity Canada. (n.d.). Retrieved April 1, 2019, from https://obesitycanada.ca/obesity-in-canada/

Redinger, R. N. (2007). The Pathophysiology of Obesity and Its Clinical Manifestations. Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 3(11), 856–863. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3104148/

Romero-Corral, A., Caples, S. M., Lopez-Jimenez, F., & Somers, V. K. (2010). Interactions Between Obesity and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Chest, 137(3), 711–719. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-0360

Sayon-Orea, C., Martinez-Gonzalez, M. A., & Bes-Rastrollo, M. (2011). Alcohol consumption and body weight: a systematic review. Nutrition reviews, 69(8), 419-431.

Spiegelman, B. M., & Flier, J. S. (2001). Obesity and the regulation of energy balance. Cell, 104(4), 531–543.

Vartanian, L. R., Schwartz, M. B., & Brownell, K. D. (2007). Effects of soft drink consumption on nutrition and health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of public health, 97(4), 667-675.

Wirth, A., Wabitsch, M., & Hauner, H. (2014). The Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Deutsches Aerzteblatt Online. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2014.0705