Table of Contents

Crohn's Disease (CD)

Introduction

What is Crohn's Disease (CD)?

Crohn disease is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory process of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract which affects any parts of the tract ranging from the mouth to the anus. It is believed to be the result of an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators. Some factors which encourages this imbalance are genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers. Hence, there is no real single factor that induces this intestinal inflammation.

Signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, and weight loss. Usually, these symptoms induce complications by intestinal fistulization and obstruction. Additionally, individuals diagnosed with this risk are at a greater risk of developing bowel cancer. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/copd>

Epidemiology

According to a National Survey analysis that was done on a geographically diverse health insurance claims database, it estimated that the prevalence of Crohn disease among US children and adults between 2003-2004 to be 201 cases per 100,000 persons among adults and 43 per 100,000 among children.

Urban areas are estimated to have a higher prevalence of IBD than rural areas do. Moreover, upper socioeconomic classes are predicted to have a higher prevalence than lower socioeconomic classes due to the difference in the access to health care between the two groups.

In general, the frequency of this disease is similar in males and females, with some studies that shows a very slight female predominance. The rate of Crohn disease is deemed to be 1.1 – 1.8 times higher in women than in men. Moreover, Crohn disease is reported to be more common in white patients than black patients, and very rare in Asian and Hispanic individuals. On average, approximately 20% of all Crohn disease patients are of black descent.

Pathophysiology

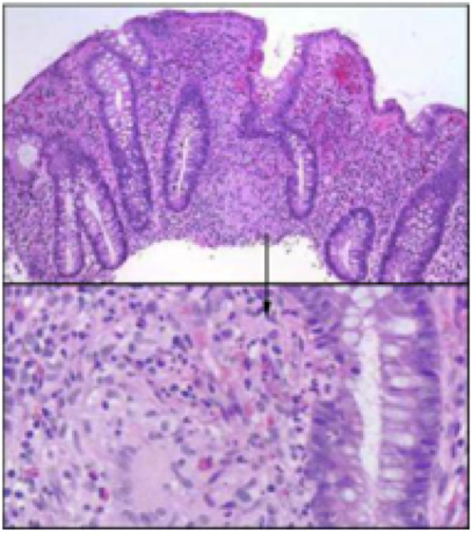

The pathophysiology of Crohn’s disease stems from a chronic inflammation from T-cell activation leading to tissue injury in the gastrointestinal tract. After the antigen activates an immune response, type 1 T-helper (Th1) cells predominate and stimulate an inflammatory response with other Th1 cytokines. Th1 cytokines include interleukin (IL)-12 and TNF-alpha that stimulate this inflammatory response. Inflammatory cells recruited by these cytokines release metabolites, proteases, and free radicals that all result in direct injury to the intestine.

According to a study conducted in 2012, researchers suggest that genetic factors for Crohns Disease leads to an abnormal observation in epithelial barrier integrity, deficits in autophagy, deficiencies in innate pattern recognition receptors, and problems with lymphocyte differentiation (Ghazi, 2016).

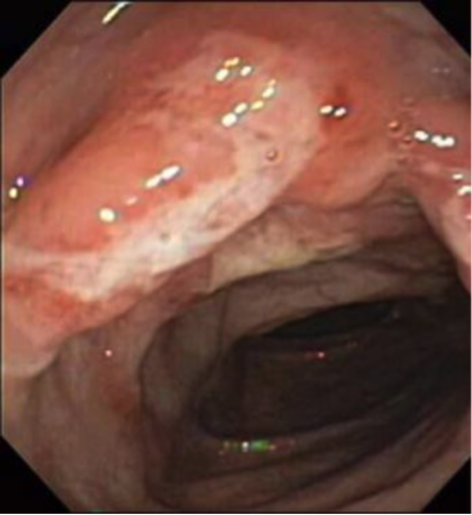

On a microscopic level, the initial lesion starts from an ulceration of the superficial mucosa. The inflammatory cells such as granulomas then invade the deep mucosal layers and start extending through all layers of the intestinal walls and into the regional lymph nodes. Although granuloma formation is the primary pathophysiologic factor of Crohn disease, its absence does not exclude the diagnosis.

Risk Factors

Family History

Studies have shown that there is a genetic factor involved in developing Crohn’s Disease. These studies propose that siblings are at a 30 Xs greater risk than the general population for developing CD (Probert et al., 1993). They are not entirely sure what the model of inheritance this genetic predisposition follows, but it does not seem to be a simple Mendelian pattern. Research shows that the condition is due to a recessive gene with incomplete penetrance. This genetic factor then combines with an environmental factor to determine their disease susceptibility. So the people at greatest risk are those that have the genetic predisposition and are exposed to some environmental factor.

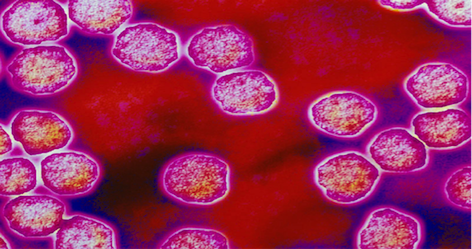

Measles Virus Measles virus infection can disrupt immune function, mainly in helper T-cell response. Many studies show the role measles virus plays in the aetiology of inflammatory bowel diseases, like Crohn’s disease. A technique called immunogold electron microscopy has confirmed the persistence of measles in Crohn’s disease affected bowel. There is a positive relationship between perinatal exposure to measles and the development of CD (Thompson., Pounder., Wakefield., & Montgomery, 1995).

Breastfeeding Measles virus infection can disrupt immune function, mainly in helper T-cell response. Many studies show the role measles virus plays in the aetiology of inflammatory bowel diseases, like Crohn’s disease. A technique called immunogold electron microscopy has confirmed the persistence of measles in Crohn’s disease affected bowel. There is a positive relationship between perinatal exposure to measles and the development of CD (Thompson., Pounder., Wakefield., & Montgomery, 1995).

Exacerbating Factors

Intercurrent infections

Intercurrent infections (both upper respiratory tract and enteric infections) have been seen to exacerbate Crohn’s disease. Many studies have examined the interaction between infections and CD and have shown that infections can initiate the onset and relapse of inflammatory bowel diseases (including CD). The disease also puts patients at a higher risk of infection and the medications to treat CD and further increase the risk. The lack or poor response to vaccinations can also play a role in infections (Irving, & Gibson, 2008).

Cigarette Smoking

Smoking cessation has a beneficial effect to patients with Crohn’s disease. Studies have shown patients with Crohn’s disease who stopped smoking for more than 1 year had a more benign disease course than if they had never smoked. Considering the rate of flare-up and therapeutic needs, disease severity was similar in patients who had never smoked and those who stopped smoking, and both had a better course than patients who continued smoking (Cosnes., Beaugerie., Carbonnel., & Gendre, 2001).

Stress Many patients and family members report stress being an influencing factor for the onset and progression of CD (Hanauer., & Sandborn, 2001). However, there have been not studies that support this relation. Researchers have not been able to link trauma events or a stressful life to the development of CD. More research must be done in this area of study to form more conclusive evidence.

Medications- Prednisone

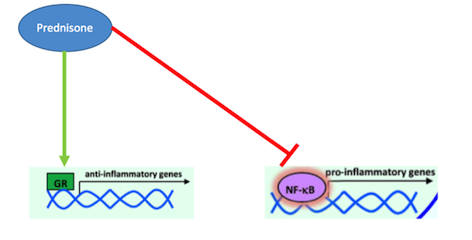

What is Prednisone? Prednisone is a corticosteroid that acts as a glucocorticoid receptor agonist in order to treat inflammatory diseases, such as Crohn’s (Barnes, 1998). Inflammation of the digestive tract is a common symptom in Crohn’s disease patients due to the pathophysiology of this disease. In the past, corticosteroids like Prednisone have been used for their immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties (Jobin & Sartor, 2000). They are able to decrease inflammation by inhibiting the actions of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thus decreasing recruitment of white blood cells, like monocytes and neutrophils, which cause inflammation (Auphan et al., 1995). Many studies have conclusively shown that pro-inflammatory cytokine, such as TNF- alpha and IFN-gamma, are responsible for the inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract that is present in Crohn’s disease patients (Wakefield et al., 1991). Typically, the anti-inflammatory response in the body is controlled by glucocorticoids. When their release is normally stimulated in the body, they will bind to intracellular, cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptors (Farell & Kelleher, 2003). These receptors will dimerize upon binding and immediately be transported to the nucleus where the regulate the transcription of target genes through block transcription of the promote NF-kappa-B. As mentioned earlier, NF-kappa-B is a potent transcription factors that, when activated, will lead the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha (Beato, Herrlich & Schutz, 1995). Research into other inflammatory disorders, such as asthma and irritable bowel syndrome, have proven that these diseases are caused by glucocorticoid resistance, which leads to an un-regulated inflammatory response, caused by increased cytokines which increase recruitment of white blood cells (Barnes, 1998). Since inflammation is a primary part of the pathophysiology of Crohn’s disease, Prednisone can effectively manage these symptoms by binding to glucocorticoid receptors and promoting their activation. By doing do, Prednisone is able to inhibit inflammatory cytokine production and thus ultimately decrease white blood cell recruitment and inflammation (Barnes, 1998).

Effectiveness

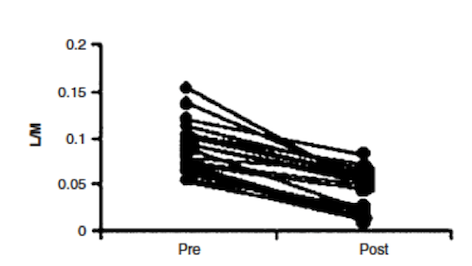

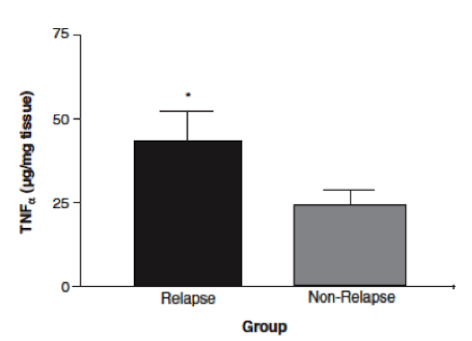

In a study done by Wild et al. (2003), effectiveness of Prednisone in the treatment of Crohn’s disease pathophysiology was illustrated. By measuring intestinal permeability and TNF-alpha levels, they were able to determine that Prednisone was effective in reducing bowel inflammation in Crohn’s disease patients. Typically, in Crohn’s disease, increased intestinal permeability to sugars and macromolecules has been illustrated (Hollander et al., 1986). Intestinal permeability can be measured using urinary clearance of lactulose to mannitol (LM ratio). This is thought to be caused by the un-regulated inflammatory response in Crohn’s disease patients, which leads to decreases in epithelial barrier integrity and thus increased intestinal permeability (Wild et al., 2003). The anti-inflammatory properties of Prednisone were measured by muscle biopsies taken endoscopically (Scheinman et al., 1995). By comparing LM ratios and muscle samples to measure TNF-alpha levels, Wild et al. were able to observe the effects of Prednisone on Crohn’s disease pathophysiology. Results indicated that LM ratios were significantly reduced after treatment with prednisone. Prednisone was seen to reduce the LM ratio by approximately 50%, indicating it was able to induce remission; however, it was no proven to maintain remission after discontinuation of the drug (Wild et al., 2003). Additionally, TNF-alpha levels were measured by comparing levels of those who relapsed immediately and those who did not. In those that did not immediately relapse, there was a reduction in TNF-alpha levels, which is indicative of decreased inflammation (Wild et al., 2003). Overall, Prednisone was seen to aid in the induction of remission of Crohn’s disease patients, illustrated by reduced LM ratios (improved intestinal permeability) and TNF-alpha levels. However, once taken off the drug, Prednisone was not proven to be effective in maintaining remission, which is difficult because individuals cannot be on prednisone for too long due to side effects, which will be discussed in the next section.

Side Effects

Corticosteroids, like Prednisone, are very effective drugs to treat the inflammation that is typically seen in Crohn’s disease patients. However, these anti-inflammatory properties are caused by the suppression of the immune system, which has many side effects on the body (Malchow & Brandes, 1984). Pro-inflammatory cytokines, like TNF-alpha, promote vasodilation and increased white blood cell migration of injury suite within the body (Scheinman et al., 1995). Since Prednisone blocks the transcription of TNF-alpha within the body, it is able to decrease the inflammatory response within the bowels of Crohn’s disease patients that TNF-alpha causes, it also supresses the other effects of the drug. A typical side effects that patients on Prednisone may experience is high blood pressure, which is associated with water retention (1 Malchow & Brandes, 19847). Additionally, decreased cytokine production prevents white blood cell recruitment to sites of injury and infection within the body, thus leading to an increase susceptibility to infections while on Prednisone because of this immunosuppressive effect (Coutinho & Chapman, 2011). Overall, Prednisone is very effective in treating Crohn’s disease pathophysiology when patients take it, but prolonged use is discouraged due to the side effects that accompany this drug.

Medications- Infliximab/ Remicade

What is Prednisone/ Remicade?

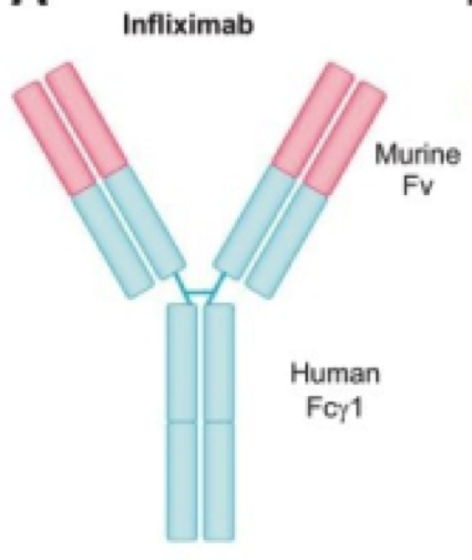

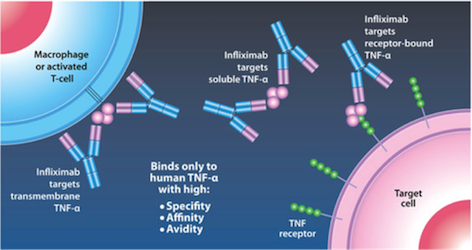

Kirman, Whelan, & Nielsen (2004) identify infliximab (trade name Remicade) is an IgG monoclonal antibody drug that targets TNF-alpha, a tumor necrosis factor. It is effective in ⅔ of Crohn’s Disease patients. The antibody is developed from mice and then replaced with human antibody domains (Kirman, Whelan, & Nielsen, 2004). Not only does infliximab treat Crohn’s Disease, but it also treats ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, plaque psoriasis (Janssen Biotech, 2016). Having an excess of TNF-alpha can cause the immune system to attack healthy cells in the GI tract leading to inflammation, and symptoms of Crohn’s Disease (Janssen Biotech, 2016).

Mechanism of Action Infliximab is given by IV infusion 6 times a year after 3 starting doses given at 0,2, and 6 weeks (Janssen Biotech, 2016). This drug can only be administered by healthcare professionals, and can even be delivered with other medications to reduce or eliminate side effects (Janssen Biotech, 2016). Infliximab binds to TNF-alpha expressing cells, as seen in Figure 8 (replace with real figure name), and precents TNF-alpha from binding to its receptor. The results of this drug are apoptosis of T-lymphocytes and monocytes, and down regulation of other inflammatory cytokines such as Th1 (Kirman, Whelan, & Nielsen, 2004). Apoptosis of monocytes is initiated by the CD95/CD95L signaling pathway and mitochondrial release of cytochrome C (Lügering et al., 2001). Cytochrome C release triggers the transcriptional activation of Bax and Bak, pro apoptotic regulators (Van Deventer, 2001).

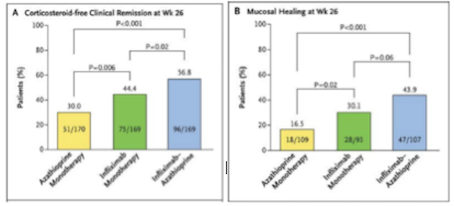

Effectiveness Infliximab is highly effective compared to other methods of treatments due to its high effectiveness and relatively low toxicity. When compared to another method of treatment, azathioprine, a purine analog working as an immunosuppressant, it has significantly better results (Colombel et al., 2010). Infliximab, seen in green on Figure 9 (replace with right number), is not more effective than a combined therapy, seen in blue. However, the combined therapy is much more toxic than the infliximab alone, therefore negates its effectiveness (Colombel et al., 2010). Furthermore, the increase in effectiveness of combined therapy is most likely due to the additive effect of using both drugs (Colombel et al., 2010).

Side Effects

There is a higher risk of infection with mycobacteria, and thus increase risk of contracting tuberculosis (Antoni & Braun, 2002). This higher risk of infection is due to the patient's immunocompromised state when taking the drug, and to avoid serious illness patients need to be informed of their immunocompromised state and educated on necessary precautions by doctors before taking infliximab (Antoni & Braun, 2002). If patients take the signs of infection seriously and report it to their doctors they will receive antibiotics right away and chances of serious infection will be drastically reduced. When patients are traveling anywhere with high rates of tuberculosis they should not receive the treatment at all, however in the USA less than 1% of the population has tuberculosis. This treatment is not administered if the patient is planning on visiting countries with higher incidence of tuberculosis because it could result in them contracting the disease (Antoni & Braun, 2002). Infliximab use has also been loosely correlated with an increased incidence of lymphoma (Antoni & Braun, 2002). There is a rare chance of acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions dye to development of human chimeric antibodies, but this is only in 10% of patients, with only 2.6% of patients discontinuing treatment due to serious infusion reactions. (Kirman, Whelan, & Nielsen, 2004). Infusion reactions symptoms are headache, dizziness and nausea (Antoni & Braun, 2002).

A positive side effect of Infliximab is that in reducing the TNF-alpha concentrations in the body, patients can see a reduction in the symptoms of other diseases. Things that have improved are rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis (Van Deventer, 2001).

Current Research

Current research is exploring the role of endogenous microbial communities in Crohn’s disease patients and healthy individuals. Researchers are concerned with dysbiosis, an imbalance in gut microbiota composition, and its association with several diseases, particularly inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s.

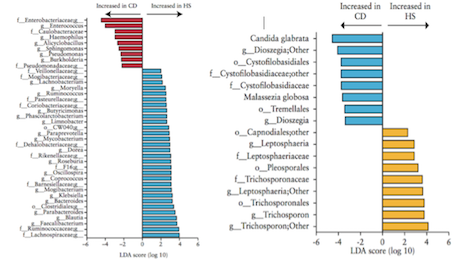

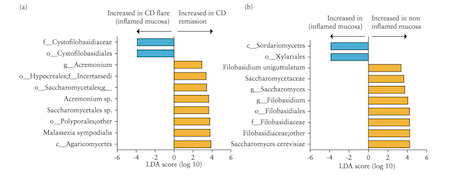

Liguori et al. (2015) A study by Liguori et al. (2015) analyzed bacterial and fungal microbiota biodiversity, and bacterial and fungal compositions present in the colonic mucosa of both Crohn’s patients and healthy subjects. Crohn’s disease was diagnosed in these patients according to classical clinical, endoscopic, and histological parameters (Liguori et al., 2015). Patients were considered healthy if they had no history or clinical symptoms of intestinal disorders or endoscopic or histological signs of irritable bowel disease (Liguori et al., 2015). Colonic mucosa specimens of Crohn’s patients were surgically acquired during oleo-colonic resection. Diseased specimens of the right colon, in both inflamed and non-inflamed mucosa, were collected. Specimens of healthy patients were sampled during colonoscopy using standardized biopsies of the right colon (Liguori et al., 2015). Liguori et al., (2015) observed a decline in biodiversity of Crohn’s disease patients samples compared with healthy subject samples. This result was true in both active and dormant Crohn’s patients, and in inflamed and non-inflamed mucosa. In Crohn’s patients, an increase of Proteobacteria was observed with a decrease of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (Liguori et al., 2015). The most major differences between Crohn’s and healthy patients were observed in the Proteobacteria and Firmicutes phyla (Liguori et al., 2015). The results also revealed a significant increase of global fungus load in Crohn’s patients when compared with healthy subjects. This was observed in both inflamed and non-inflamed mucosa (Liguori et al., 2015).

Hoarau et al. (2016) Another study conducted by Hoarau et al. (2016) outlines five major findings.

1. Microbiotas of familial samples are distinct from those of nonfamilial samples (Hoarau et al., 2016) Gut samples collected from related individuals indicated greater similarities to each other regardless of their Crohn’s disease status. This provides insight for identifying organisms linked to the disease by comparing the microbiotas within affected and unaffected family members (Hoarau et al., 2016).

2. Abundance of potentially pathogenic bacteria is increased while beneficial bacteria are decreased in CD (Hoarau et al., 2016) An increased abundance of potentially pathogenic bacterial species, such as Escherichia coli and Serratia marcescens, were found in the samples of Crohn’s patients compared to healthy subjects. The team identified the abundance of 11 genera and 15 species that differed significantly in Crohn’s patients (Hoarau et al., 2016).

3. Candida tropicalis abundance is significantly increased in CD patients (Hoarau et al., 2016) Correlations between C. tropicalis abundance and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) levels were investigated because the yeasts of the genus Candida are described as immunogens for Crohn’s Disease biomarkers designated ASCAs. The ASCA level was significantly higher in Crohn’s patients than in the healthy group. C. tropicalis was also the only fungus that was positively associated with ASCA (Hoarau et al., 2016).

4. CD is associated with inter- and intrakingdom correlations (Hoarau et al., 2016) Hoarau et al. (2016) found several significant associations at the genus and species levels in both bacteria and fungi. Moreover, C. tropicalis demonstrated significantly positive associations with 13 bacterial species, including E. coli and S. marcescens (Hoarau et al., 2016).

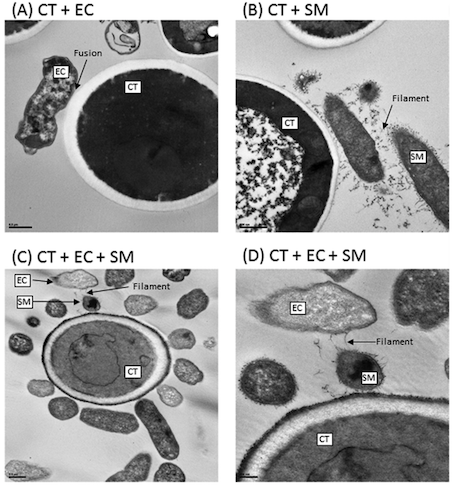

5. Biofilm formation mediates interkingdom interactions in CD (Hoarau et al., 2016) The analysis of a method called scanning electron microscopy (SEM) showed that biofilms formed by C. tropicalis alone comprised yeast forms while the biofilms formed by a combination of C. tropicalis and either E. coli or S. marcescens were enriched in fungal hyphae, a form of growth associated with pathogenic conditions (Hoarau et al., 2016).

Figure 12: Interactions of Transmission electron microscopy analyses of biofilms formed by C. tropicalis alone or in combination with E. coli and/or S. marcescens. (A) C. tropicalis plus E. coli; (B) C. tropicalis plus S. marcescens; (C) C. tropicalis plus E. coli plus S. marcescens (bar, 0.5 m); (D) C. tropicalis plus E. coli plus S. marcescens (bar, 200 nm). Modified from Hoarau et al. (2016).

Conclusion

A lot of research still needs to be done in order to better understand Crohn’s Disease. Genetic factors are linked with Crohn’s disease and increases the risk of diagnosis. The risk is much greater in individuals of similar familial background than those who are unrelated. Measles viral infections are also a confirmed risk factor of Crohn’s disease. Knowledge of risk may result in better preparation before diagnosis and more applicable treatments following diagnosis. Genetically susceptible individuals may engage in necessary measures to avoid triggering the disease symptoms while others may take precautions by receiving appropriate immunizations.

Awareness of certain factors that exacerbate Crohn’s is valuable for disease treatment and management. Avoiding habits which jeopardize optimal health in Crohn’s patients, such as cigarette smoking and use of contraceptives, may lead to fewer flares and discomfort experienced by these individuals. Crohn’s patients may also seek alternative methods to satisfy these habitual needs.

Treatment depends on the severity of each case, but medication is available for a large proportion of patients. Prednisone and infliximab/ remicade are both examples of effective pharmaceuticals prescribed to manage existing cases of Crohn’s. Current research suggest that there may be specific microbiota associated with Crohn’s disease. Recent findings on microbial communities is promising and may be pivotal point in Crohn’s disease history and treatment discovery, development, and approach.

References

Antoni, / C, & Braun, J. (2002). Side effects of anti-TNF therapy: Current knowledge. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology, 20, s152-7.

Auphan, N., DiDonato, J.A., Rosette, C., Helmberg A, Karin M. (1995). Immunosuppression of glucocorticoids: inhibition of NF-jB activity through induction of IjB synthesis. Science. 270, 286–90.

Barnes, P.J. (1998). Anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids: molecular mechanisms. Clin Sci. 94, 557–72.

Beato, M., Herrlich, P., Schutz, G. (1995). Steroid hormone receptors: many actors in search of a plot. Cell. 83, 851–857.

Colombel, J. F., Sandborn, W. J., Reinisch, W., Mantzaris, G. J., Kornbluth, A., Rachmilewitz, D., … Rutgeerts, P. (2010). Infliximab, Azathioprine, or Combination Therapy for Crohn’s Disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 362(15), 1383–1395. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0904492

Coutinho, A.E., Chapman, K.E. (2011) The Anti-inflammatory and Immunosuppressive Effects of Glucocorticoids, recent developments and Mechanistic Insights. Mole Cell Endocrinol. 335, 2-13.

Farell, R.J., Kelleher, D. (2003). Mechanisms of Steroid Actions and Resistance in Inflammation: Glucocorticoid Resistance in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Journal of Endocrinology. 178, 339-346.

Hanauer, S. B., & Sandborn, W. (2001). Management of Crohn's disease in adults. The American journal of gastroenterology, 96(3), 635.

Hoarau, G., Mukherjee, P. K., Gower-Rousseau, C., Hager, C., Chandra, J., Retuerto, M. A., . . . Ghannoum, M. A. (2016, September 20). Bacteriome and Mycobiome Interactions Underscore Microbial Dysbiosis in Familial Crohn’s Disease. MBio, 7(5). doi:10.1128/mbio.01250-16.

Hollander, D., Vadheim, C. M., Brettholz, E., Petersen, G. M., Delahunty, T., & Rotter, J. I. (1986). Increased intestinal permeability in patients with Crohn's disease and their relatives: a possible etiologic factor. Annals of internal medicine, 105(6), 883-885.

Irving, P. M., & Gibson, P. R. (2008). Infections and IBD. Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 5(1), 18-27.

Janssen Biotech. (2016). How REMICADE® Works | REMICADE® (infliximab). Retrieved from http://www.remicade.com/crohns-disease/how-remicade-works.

Jobin, C., Sartor, R.B. (2000). NF-jB signaling proteins as therapeutic targets for inflammatory bowel diseases. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 6, 206–13.

Kirman, I., Whelan, R. L., & Nielsen, O. H. (2004). Infliximab: mechanism of action beyond TNF-alpha neutralization in inflammatory bowel disease. European Journal of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 16(7), 639–41. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15201575

Koletzko, S., Sherman, P., Corey, M., Griffiths, A., & Smith, C. (1989). Role of infant feeding practices in development of Crohn's disease in childhood. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 298(6688), 1617.

Liguori, G., Lamas, B., Richard, M. L., Brandi, G., Costa, G. D., Hoffmann, T. W., . . . Sokol, H. (2015). Fungal Dysbiosis in Mucosa-associated Microbiota of Crohn’s Disease Patients. ECCOJC Journal of Crohn's and Colitis, 10(3), 296-305. doi:10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv209

Lügering, A., Schmidt, M., Lügering, N., Pauels, H. G., Domschke, W., & Kucharzik, T. (2001). Infliximab induces apoptosis in monocytes from patients with chronic active Crohn’s disease by using a caspase-dependent pathway. Gastroenterology, 121(5), 1145–57. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11677207

Malchow, H., Ewe, K., Brandes, J.W., et al. (1984) European cooperative Crohn’s disease study (ECCDS): results of drug treatment. Gastroenterology. 86, 249–66. Probert, C. S., Jayanthi, V., Hughes, A. O., Thompson, J. R., Wicks, A. C., & Mayberry, J. F. (1993). Prevalence and family risk of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease: an epidemiological study among Europeans and south Asians in Leicestershire. Gut, 34(11), 1547-1551.

Scheinman RI, Cogwell PC, Lofquist AK & Baldwin Jr AS (1995) Role of transcriptional activation of I_B_ in mediation of immunosuppression by glucocorticoids. Science; 270: 283–286.

Thompson, N. P., Pounder, R. E., Wakefield, A. J., & Montgomery, S. M. (1995). Is measles vaccination a risk factor for inflammatory bowel disease?. The Lancet, 345(8957), 1071-1074.

Timmer, A., Sutherland, L. R., & Martin, F. (1998). Oral contraceptive use and smoking are risk factors for relapse in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology, 114(6), 1143-1150.

Van Deventer, S. J. H. (2001). Transmembrane TNF-α, induction of apoptosis, and the efficacy of TNF-targeting therapies in Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterology, 121(5), 1242–1246. https://doi.org/10.1053/gast.2001.29035

Wakefield, A. J., Sawyerr, A. M., Hudson, M., Dhillon, A. P., & Pounder, R. E. (1991). Smoking, the oral contraceptive pill, and Crohn's disease. Digesive diseases and sciences. 36, 1147-1150.

Wild, G.E., Waschke, K.A., Bitton, A., Thomson, A.B.R. (2003). The Mechanisms of Prednisone Inhibition of Inflammation in Disease In Crohn’s Disease Involve Changes in Intestinal Permeability, Mucosal TNF alpha Production and Nuclear factor kappa B expression. Ailment Pharmacol Theory. 18, 309-317.