This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Albinism

Introduction

Albinism is characterized as the absence of pigmentation found throughout the body. It is a congenital disorder meaning that it’s effects can be seen from birth, and it can affect both plants as well as animals, ranging from humans to reptiles as an example. In humans, albinism causes changes to the colour of the eyes, skin, and hair, which appear lighter in colour (Ablbinism, 2018). Some of the symptoms that appear with albinism include a number of vision defects, as well as increased rates of sunburning and skin cancer due to a lack of skin pigmentation (Ablbinism, 2018). In some rare cases, Albinism may also cause deficiency in immune function and increase the rates of certain infections (Ablbinism, 2018).

Albinism is a recessive genetic disorder and results from inheritance of two alleles containing the mutation. However, due to its recessive nature, the parents of the offspring may or may not be displaying the phenotype while being carriers of the mutated alleles (Ablbinism, 2018). Albinism occurs due to a mutation that codes for the enzyme tyrosinase, where it is either absent or defective. Tyrosinase is involved in the production of melanin (Ablbinism, 2018).

Epidemiology

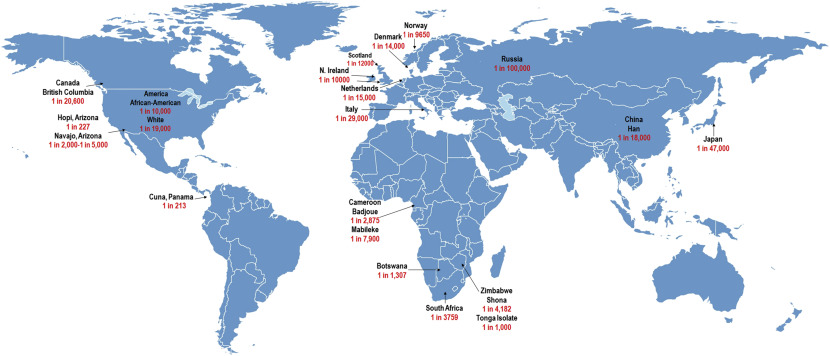

The epidemiology of albinism is still poorly understood, but studies have demonstrated that incidence varies from region to region, and does not preferentially affect one sex over another. In Africa, albinism has an incidence rate of 1 in 4000-5000. In Europe, the incidence rate is roughly 1 in 20,000. In China, the incidence rate is 1 in 18,000. In the United States, the incidence rate is 1 in 16,000. However, incidence rate has been shown to change based on population and genetics, one example is the American Indian Hopi tribe from Arizona which has a much higher incidence rate compared to the rest of the country (1 in 227). Thus, demonstrating that this disease is largely genetic in nature (Kromberg, 2018).

The prevalence of types of albinism also vary by ethnic group and location. For example, in the United States, OCA2 is the most common form of albinism and disproportionately affects African Americans and Africans. The estimated frequency is 1 in 10,000 in African-Americans compared with caucasians being 1 in 36,000 (Bashour, 2018).

Etiology

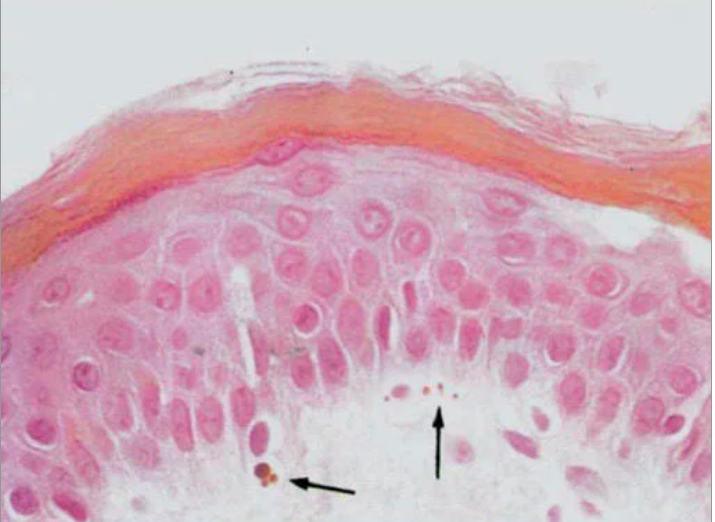

The cause of albinism is genetic in nature, with specific loci identified for each type of albinism. From the albinism database compiled by the University of Minnesota, the following loci have been identified for the following types of albinism (Albinism Database, 2009).

Risk Factors

It has been established that albinism is an inherited genetic disorder. In order for a person to have albinism, both of their parents must carry the albinism gene. This is due to the fact that the albinism gene is a recessive gene, therefore the offspring has to receive a copy from both parents to have the disorder (Porter, 2018). Thus, those who are at risk of developing albinism include:

- Children of parents whom both have albinism

- Children of parents whom do not have albinism but both carry the albinism gene

- Positive family history for albinism (siblings or relatives)

- Males as X-linked ocular albinism exclusively affects males

- Being of sub-Saharan African or Puerto Rican heritage (“Albinism”, 2017)

Symptoms

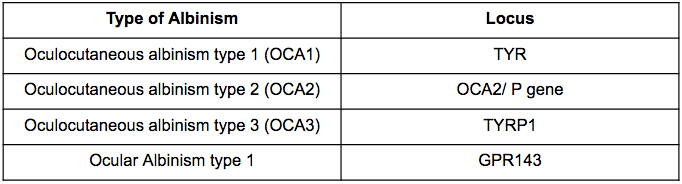

The symptoms of OCA (oculocutaneous albinism) are seen as various alterations among the pigmentation of the skin, hair and eyes for an individual (U.S. National Library of Medicine [U.S. NLM], 2018). This is caused by minimal or completely no production of melanin in the body (U.S. NLM, 2018). Since melanin affects the development of optic nerves as well, affected individuals experience vision complications (U.S. NLM, 2018).

OCA Type 1 is characterized by a complete absence in pigmentation or highly reduced pigmentation in the skin, colour of irises and hair (U.S. NLM, 2018). This results in paleness, white hair and lighter coloured irises (U.S. NLM, 2018). On the other hand, OCA Type 2 pigmentation symptoms have less severity (U.S. NLM, 2018). This is seen as affected individuals display creamy white skin and light yellow or brown hair (U.S. NLM, 2018). When examining vision problems among Type 2 individuals, they are similar symptoms as Type 1 (U.S. NLM, 2018). Both types have forms of visual impairment including nystagmus; which involves rapid involuntary eye movements and light sensitivity; called photophobia (U.S. NLM, 2018). Additionally, patients experience a range of other symptoms including decreased vision and depth perception, strabismus, astigmatism and more (U.S. NLM, 2018). Type 3 is correlated to rufous oculocutaneous albinism, which is a different form of albinism that targets dark-skinned individuals (U.S. NLM, 2018). Patients with Type 3 have red-bronze skin, ginger hair and blue or brown irises (U.S. NLM, 2018). This Type 3 category also consists of more moderate vision abnormalities compared to Type 1 and 2 (U.S. NLM, 2018).

The other primary form of albinism is OA (ocular albinism) which only results in symptoms in the eyes (U.S. NLM, 2018). Characteristic features that can be observed include severe negative impacts on visual acuity, depth perception, iris translucency, and other visual symptoms stated previously (U.S. NLM, 2018).

Figure 1: Symptoms observed in the skin, hair, lashes and eyes of an individual affected by OCA 1 (Hertle, 2013).

Figure 1: Symptoms observed in the skin, hair, lashes and eyes of an individual affected by OCA 1 (Hertle, 2013).

Diagnosis

There are steps that can be taken in order to determine which type of albinism a patient has. To begin with, a doctor can assess the phenotype of the patient. Complete depigmentation of skin and hair will indicate there is a likelihood that the patient has OCA 1A (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). To confirm this, a hair bulb assay can be conducted (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). The hair bulb taken from the scalp can indicate the catalytic activity of tyrosinase through a histochemical procedure or radioactive biochemical assay (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). The histochemical procedure involves incubation of the samples in the substrate DOPA, this can demonstrate the induction of melanin (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). The other method, a radioactive biochemical assay will involve incubating the samples with a radiolabelled tyrosine precursor (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). This way, the results can show how much radiolabel is released after enzymatic conversion, by measuring with a spectrophotometer (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). A negative result through each of these assays will confirm OCA 1A (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998).

If a patient demonstrates partial depigmentation, this indicates the patient could have OCA 1B, OCA 2 or OCA 3 (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). To further diagnose which type of albinism the individual has, genetic sequence analysis; the most definitive test for this can be used (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). This type of analysis will examine genes encoding tyrosinase, P protein and TRP-1 (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). Another procedure that can be done is creating cultures of melanocytes from a skin biopsy, to look at the function and expression of these 3 proteins (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998).

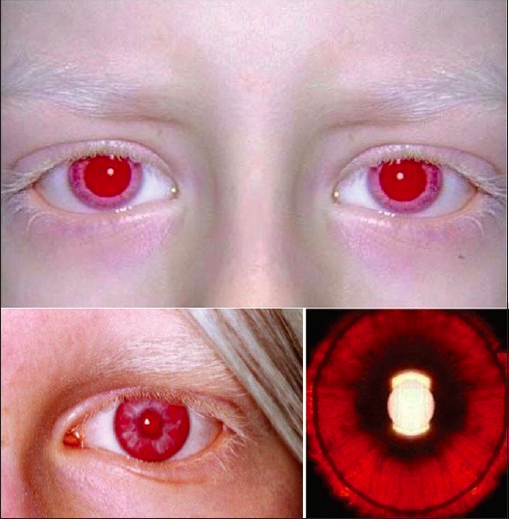

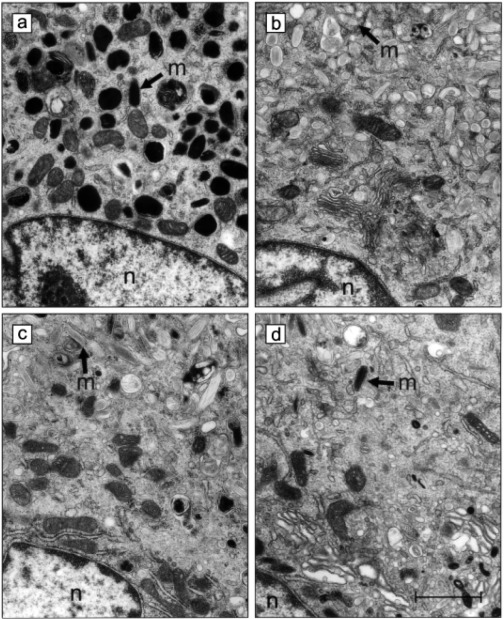

Lastly, if the patient exhibits eye symptoms that match the phenotype of individuals with ocular albinism (OA 1), females need to be checked for carrier status (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). This status is indicated by a mud-splattered fundus (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). Next, a skin histology examination can be taken to detect macromelanosomes, known as giant melanosomes in pigmented skin lesions (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998).

Figure 2: Histology from skin biopsy displaying macromelanosomes (Shiono, Tsunoda, Chida, Nakazawa, & Tamai, 1995).

Figure 2: Histology from skin biopsy displaying macromelanosomes (Shiono, Tsunoda, Chida, Nakazawa, & Tamai, 1995).

Pathophysiology and Mechanisms

Pathology

There two main types of albinism. The first type is called ocular albinism(OA), a rare x-linked recessive disorder caused by mutations on the x-chromosome (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). The second and most common type of albinism is called oculocutaneous albinism (OCA)(Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). This is a group of heterogeneous autosomal recessive disorders that are caused by many different gene mutations that compromise melanin production (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998).

Mechanisms

There are three main types of Oculocutaneous albinism (OCA).

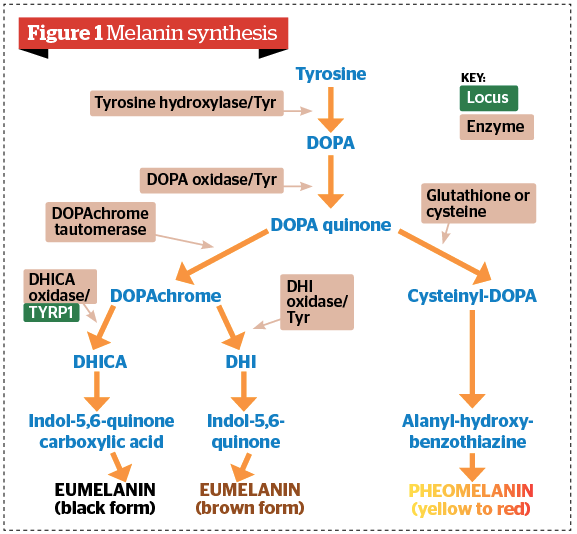

OCA1: It is caused by a mutation in the tyrosinase gene (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). This gene mutation is found to be on chromosome 11, caused by a nonsense, frameshift, or missense mutations(Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). Tyrosinase is essential for the biosynthesis of melanin by catalyzing 3 main steps in the biosynthesis process of melanin (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). Therefore without it, little to no melanin will be produced, causing albinism.

Figure 3: The biosynthesis of melanin, including the three important catalyzing reactions of tyrosinase (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998).

Figure 3: The biosynthesis of melanin, including the three important catalyzing reactions of tyrosinase (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998).

OCA2: It is caused by a mutation in the human P-gene (Puri, Gardner & Brilliant, 2000). The function of the gene product of this gene is not fully known. However, it is thought that the P-protein maintains the right PH of melanosomes (acidification) and also targets necessary molecules that are involved in the production of melanin such as tyrosine, into the melanosome (Puri, Gardner & Brilliant, 2000). Therefore without this protein, the PH levels of the melanosome will no longer be maintained and the transportation of tyrosine into the melanosome to produce melanin, will be compromised (Puri, Gardner & Brilliant, 2000).

Figure 4: a) A functioning melanosome (m) producing melanin. (b,c,d) A mutated P protein causing a deficiency of melanin production in the melanosome (m) (Puri, Gardner & Brilliant, 2000).

Figure 4: a) A functioning melanosome (m) producing melanin. (b,c,d) A mutated P protein causing a deficiency of melanin production in the melanosome (m) (Puri, Gardner & Brilliant, 2000).

OCA3: It is caused by mutation in the TRP-1 gene (tyrosine related protein 1)(Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). This mutation is located on chromosome 9(Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). TRP-1 is a protein that regulates the production of black melanin(Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998). A defect in that protein will disrupt the production of black melanin, producing brown melanin instead. This disease is mostly present in black patients (Carden, Boissy, Schoettker, & Good, 1998).

Figure 5: The biosynthesis of melanin, highlighting the important role of TRP-1 protein in regulating the production of black melanin (“Facial hyperpigmentation in skin of colour: PRIME Journal”, 2018).

Albinism and Skin Cancer

Albinism is characterized by hypopigmentation of the eyes, skin and hair due to the lack of cutaneous melanin pigment production. Melanin is a protective pigment which protects the skin from the harmful effects of ultraviolet radiation. The deficiency of melanin in people with albinism is what puts them at a high risk of developing extreme sun sensitivity and skin cancer (Mabula et al., 2012). High level of exposure to ultraviolet radiation increases the risk of all three major forms of skin cancer – basal cell cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma (Yurtoğlu, 2010). Although albinism affects people of all ethnic background and has a worldwide distribution, the highest incidence of albinism occurs in Africa. This is evident as the frequency of albinism can be as high as 1 in 2,500 people in Tanzania to 1 in 4,000 people in Zimbabwe (Mabula et al., 2012). It was found that squamous cell carcinoma was the most common skin cancer seen in albinos. In addition, the head and the neck were the sites most commonly affected (Yakubu & Mabogunje, 1993).

Figure 6: Incidence of albinism in most prevalent countries (Kromberg, 2018)

Figure 6: Incidence of albinism in most prevalent countries (Kromberg, 2018)

In Africa, the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in normally pigmented population ranges from 7.8 – 16% of all diagnosed skin malignancies. Whereas in the African albino population, the risk of developing these cancers has been reported to be almost 1000-fold (Mabula et al., 2012). From available studies, it was found that skin cancers in albinos are preventable. This can be done through various skin protective measures such as sun-screening agents, protective clothing, reducing time spent outdoor and early treatment (Yurtoğlu, 2010). The lack of information on the connection between albinism and skin cancer plays a major role in worsening this situation. To address this, the public (especially those with albinism) should be educated on early institution of preventive measures. In addition, the government should provide treatment funds for albinos with low socioeconomic status to reduce the high rates of skin cancer among albinos (Mabula et al., 2012).

Figure 7: An image of squamous cell carcinoma on the head of a patient (Yurtoğlu, 2010)

Figure 7: An image of squamous cell carcinoma on the head of a patient (Yurtoğlu, 2010)

Treatment

Albinism is both congenital and genetic, meaning that it is present for birth and cannot be cured. However, many of its symptoms can be treated.

One of the most common symptoms of Albinism are several conditions affecting sight. Surgery may be recommended for patients suffering from strabismus (cross-eyes). Corrective lenses or laser eye surgery may also be used to treat poor visual acuity. Some people with albinism may also suffer from light sensitivity due to on pigmentation in their iris. In these instances, sunglasses are usually employed to block UV light.

Albinism also leaves skin to be vulnerable to sunlight, making it easier to get burned and develop skin cancer. It is therefore recommended that people with Albinism limit their time in the sun as well as use high SPF sunscreen along with frequent checks by a dermatologist.

Since the disorder is genetic, couples worried that their offspring my inherit the disorder can be screened for genetic mutations that are known to cause the condition.

Final Remarks

In conclusion, Albinism is a disorder that has long been observed. It has been seen in humans, plants, and animals alike. Although living with Albinism may come with it’s own set of obstacles, the majority of those born with then condition may be able to live a relatively normal lifestyle. Having Albinism may mean having to wear glasses and watch exposure to the sun, however other complications are relatively rare if the disorder is correctly managed. Due to recent advances in technology, couples with a history of Albinism in the family may also be able screen for the condition if they are concerned.

References

Albinism. (2017, April 27). Retrieved November 24, 2018, from https://www.dovemed.com/diseases-conditions/albinism/

Albinism Database. (2009, September 1). Retrieved November 26, 2018, from http://www.ifpcs.org/albinism/

Bashour, M., Dr. (2018, November 08). Albinism. Retrieved from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1200472-overview

Carden, S. M., Boissy, R. E., & Schoettker, P. J. (1998, February 01). Albinism: Modern molecular diagnosis. Retrieved from https://bjo.bmj.com/content/82/2/189.full

Hertle, R. (2013). Albinism: Particular Attention to the Ocular Motor System. Middle East African journal of ophthalmology. 20. 248-255. 10.4103/0974-9233.114804.

Kromberg, J. G. (2018). Epidemiology of Albinism. In Albinism in Africa (pp. 57-79).

Mabula, J. B., Chalya, P. L., Mchembe, M. D., Jaka, H., Giiti, G., Rambau, P., . . . Gilyoma, J. M. (2012). Skin cancers among Albinos at a University teaching hospital in Northwestern Tanzania: A retrospective review of 64 cases. BMC Dermatology, 12(1). doi:10.1186/1471-5945-12-5

Oculocutaneous albinism - Genetics Home Reference - NIH. (2018, November 20). Retrieved from https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/oculocutaneous-albinism#

Porter, D. (2018, April 13). Who Is At Risk for Albinism? Retrieved November 24, 2018, from https://www.aao.org/eye-health/diseases/albinism-risk

Puri, N., Gardner, J., & Brilliant, M. (2000). Aberrant pH of Melanosomes in Pink-Eyed Dilution (p) Mutant Melanocytes. Journal Of Investigative Dermatology, 115(4), 607-613. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00108.x

Shiono, T., Tsunoda, M., Chida, Y., Nakazawa, M., & Tamai, M. (1995). X linked ocular albinism in Japanese patients. The British journal of ophthalmology, 79(2), 139-43.

Yakubu, A., & Mabogunje, O. A. (1993). Skin Cancer in African Albinos. Acta Oncologica, 32(6), 621-622. doi:10.3109/02841869309092440

Yurtoğlu, N. (2010). Albinism and Skin Cancer. History Studies International Journal of History, 10(7), 241-264. doi:10.9737/hist.2018.658