Table of Contents

Osteoporosis

History

Osteoporosis is a medical condition characterized by low bone density and deterioration

of bone matrix in connective tissues (Melton, 2001). Osteoporosis usually occurs after 50 years of age and impacts millions of Canadians and people around the globe. Osteoporosis induced injuries can result in prolonged hospitalization, decreased independence, higher incidence of depression, and a reduced quality of life (Iqbal, 2000). Osteoporosis results in significant personal and economic damage, with estimated costs of a yearly $13.8 billion for direct medical treatment in the United States (Iqbal, 2000).

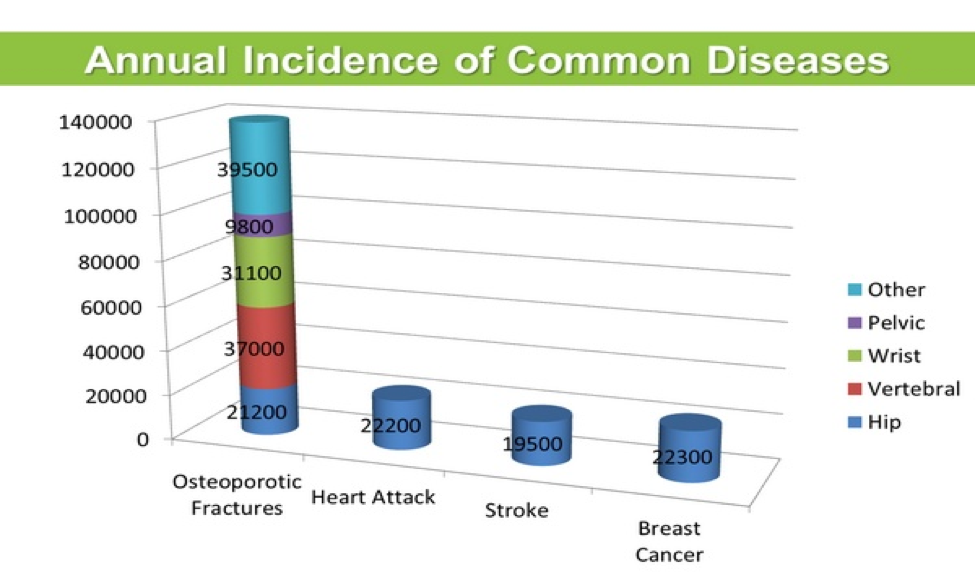

Research shows that approximately 20% of men over 50 years old are diagnosed with osteoporosis of the hip, spine or wrist. Furthermore, about 50% of women will suffer an osteoporotic fracture at some point in their life. The World Health Organization defines osteoporosis on the basis that an individual has a bone mineral density (BMD) of more than 2.5 standard deviations below the normal mean. Particularly, postmenopausal women have higher risks of developing osteoporosis due to declines in estrogen levels. A survey by the National Health and Nutrition institute in the United States, revealed that 20% of white postmenopausal women had osteoporosis of the femoral neck compared to 10% of Hispanic women and 5% of African-American women. In this same study, the prevalence of osteoporosis among white, Hispanic, and African-American men was 4%, 2%, and 3%, respectively (Melton, 2001). The following figure shows the annual incidence of common diseases in Canada and it is clearly evident that osteoporotic fractures are more common than heart attacks, stroke and breast cancer (Grant, 2015).

Osteoporosis is a medical condition characterized by low bone density and deterioration

of bone matrix in connective tissues (Melton, 2001). Osteoporosis usually occurs after 50 years of age and impacts millions of Canadians and people around the globe. Osteoporosis induced injuries can result in prolonged hospitalization, decreased independence, higher incidence of depression, and a reduced quality of life (Iqbal, 2000). Osteoporosis results in significant personal and economic damage, with estimated costs of a yearly $13.8 billion for direct medical treatment in the United States (Iqbal, 2000).

Research shows that approximately 20% of men over 50 years old are diagnosed with osteoporosis of the hip, spine or wrist. Furthermore, about 50% of women will suffer an osteoporotic fracture at some point in their life. The World Health Organization defines osteoporosis on the basis that an individual has a bone mineral density (BMD) of more than 2.5 standard deviations below the normal mean. Particularly, postmenopausal women have higher risks of developing osteoporosis due to declines in estrogen levels. A survey by the National Health and Nutrition institute in the United States, revealed that 20% of white postmenopausal women had osteoporosis of the femoral neck compared to 10% of Hispanic women and 5% of African-American women. In this same study, the prevalence of osteoporosis among white, Hispanic, and African-American men was 4%, 2%, and 3%, respectively (Melton, 2001). The following figure shows the annual incidence of common diseases in Canada and it is clearly evident that osteoporotic fractures are more common than heart attacks, stroke and breast cancer (Grant, 2015).

Risk Factors

Osteoporosis can happen due to insufficient adolescent bone density, fluctuation in hormone levels leads to imbalances and an overall nutrient poor diet. During adolescence or puberty, bone density continuously increases and peak levels are reached when an individual is in their early 20’s. Following this age, osteoclast activity tends to surpass the osteoblast activity and rate of bone formation declines. Studies have revealed that a low peak bone density during puberty may induce a greater risk of developing osteoporosis when one is an adult (Schettler & Gustafson, 2004). Hormonal imbalances can occur because of an overactive or underactive thyroid and this phenomenon can in turn increase susceptibility to osteoporosis. Moreover, males who have low testosterone levels and females who have low estrogen levels, have a significantly greater risk of developing osteoporosis. A diet that is poor in Vitamin D or calcium can significantly decrease bone density (Larsen, Mosekilde & Foldspang, 2003). Calcium is deposited into trabecular bone during osteogenesis and without this essential element, bone growth occurs significantly slower and the overall structure may turn unstable. Vitamin D is essential for the small intestines as they use this vitamin to absorb calcium which is in turn supplied to the bones via the blood stream. Therefore, Vitamin D is vital to bone growth and insufficient amounts are indeed risk factors for osteoporosis.

Signs and Symptoms

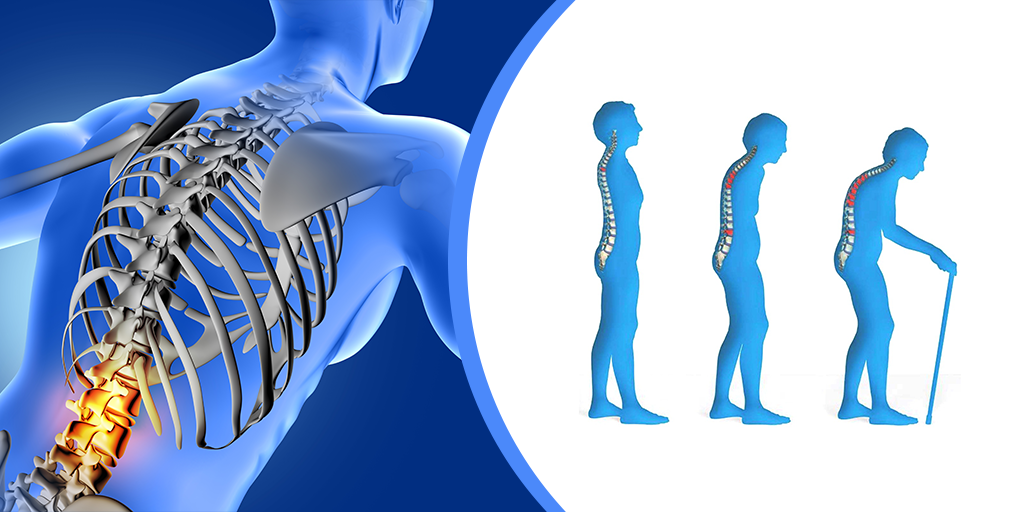

For individuals that have osteoporosis, treating this disease early on is the best way to prevent more serious risks, but being able to detect bone loss signs early on is really unusual (Minnis, 2016). A couple signs that have been visible for individuals with osteoporosis in the early age include having a weaker grip strength, weaker fingernails, and receding gums (Minnis, 2016). As the individual enters a later stage of osteoporosis, an increase in bone loss is observed (Minnis, 2016). At this stage, the individual begins to observe more obvious signs (Minnis, 2016). These signs include neck and back pain, fractures that occur from a fall, getting a hunched back, and a loss of height (Minnis, 2016). For individuals with osteoporosis, areas of fracture include hip, wrist, and spine (Minnis, 2016).

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of osteoporosis is dependent on many factors such as the pathology and histology of the disease, the hormonal regulation of bone metabolism, bone mineral density (BMD), the type of fracture the individual had/has and the models for risk of fracture predictions (Lorentzon & Cummings, 2015).

Endocrine Regulation

Riggs and Melton (1993), believed that the diagnosis of osteoporosis can be divided into two types of osteoporosis, this being so:

Type 1: this type of osteoporosis is due to low levels of oestradiol and the loss of trabecular bone following a few years after menopause in women

Type 2: this type of osteoporosis is due to ageing with dysfunctional calcium handling, which results in reduced levels of vitamin D, lead to hip/spine fractures. After many other researchers tried to confirm this, it was found that this method of diagnosis was not correct. This was because osteoporosis and fractures tend to occur many years after menopause not in the first couple of years which, was claimed by, Riggs and Melton. Also, low levels of oestradiol were associated with hip/spine fractures but not low levels of Vitamin D.

Bone mineral density

Bone mineral density also known as BMD, can be used to measure the density of all bones in the body. Historically, single photon absorptiometry was used which, did not measure all bones in the body (Cameron, 1963). In present day, dual energy x-rays absorptiometry (DXA) is being used to measure the bone mineral density in peripheral/axial skeletal sites (Lorentzon & Cummings, 2015). This method is much more efficient, and accurate compared to the historical methods (Lorentzon & Cummings, 2015). It has been determined that if the patients femoral neck BMD is 2.5 SD below, the average young, healthy person has osteoporosis (Lorentzon & Cummings, 2015). The BMD tends to decrease because of age and other external factors. Research on the efficacy of DXA was tested on human cadavers via measuring the BMD of actual bones and it was seen to be a good proxy (Cheng et al., 1997).

Risk Models

There are a lot of risk factors that are associated with osteoporosis. These factors include, age, previous fractures (low-trauma in adulthood), smoking, oral glucocorticoid usage, rheumatoid arthritis and alcohol use (WHO, 2007). Both smoking and alcohol are dosage dependent (WHO, 2007). These risk factors come together and make up the FRAX calculator (Lorentzon & Cummings, 2015). This is available online and is country specific since there are many geological variations (Lorentzon & Cummings, 2015). The FRAX model gives an approximate 10-year probability of any hip fracture or major fracture, that might occur in an individual (FRAX, n.d.).

Pathophysiology

Osteoporosis is a systemic disease of the bones characterized by a low skeletal bone density and mass, as well as deterioration of bone tissues. Together, these cause an individual with osteoporosis to have an increased risk of bone fracture (Garnero, 2008).

That being said, there are two classifications of osteoporosis identified; primary and secondary. Most commonly seen is primary osteoporosis which includes type 1 and type 2 which are postmenopausal osteoporosis and senile osteoporosis, respectively. On the other hand, secondary osteoporosis is characterized by bone mass loss from certain diseases. In addition, secondary osteoporosis is also caused from poor health choices like smoking and consumption of alcoholic beverages. Within primary osteoporosis, type 1 is associated with a loss of the hormones, estrogen and androgen, leading to increased bone turnover, bone resorption exceeds bone formation and dominant loss of trabecular bone rather than cortical bone. Type 2 osteoporosis is defined by predominant loss of cortical bone, and results from age related bone loss caused by systemic senescence and is induced by loss of stem-cell precursors (Dobbs, Buckwalter, & Saltzman, 1999).

Around the ages between 40 and 50, bone mass starts to decrease in both men and women at a yearly rate of 0.3 to 0.5 percent. In fact, postmenopausal women experience an increase in the loss of bone mass by as much as 10 times. Similarly, this increased rate also occurs in men after castration, when there is loss of function of the testicles (Dobbs, Buckwalter, & Saltzman, 1999).

Treatments - Prevention & Management

Unfortunately, there is no cure for osteoporosis as it is a symptom from ageing, however there are many prevention and management methods to reduce its severity. Thus, the current treatment methods are targeted at preventing the progression of osteoporosis, which include changes to one's lifestyle and drugs that reduce bone loss, increase bone strength and bone formation (Kling, Clarke, & Sandhu, 2014).

Lifestyle

There are many lifestyle modifications that individuals can engage in to reduce the detriments of osteoporosis and prevent its progression. Since one component of bones is calcium, one recommendation is to include more foods rich in calcium in one’s diet. Some examples of calcium rich foods are dairy products like milk or yogurt, leafy dark green vegetables, nuts and calcium-fortified foods. Additionally, there are calcium supplements available like calcium citrate and calcium carbonate that an individual can take. Together, these foods and supplements will aid in building bone strength and reducing the progression of osteoporosis (NYU Langone Health, n.d.).

Another vitamin that will help in preventing osteoporosis from progressing is vitamin D. Similar to calcium, there are foods and supplements available that an individual with osteoporosis can take. Examples include fatty fish like tuna or salmon, beef liver, cheese and egg yolks, as well as vitamin D supplements one can obtain over the counter. That being said, vitamin D works by promoting calcium absorption in the intestines and aids in the maintenance of balanced calcium levels. Moreover, vitamin D supplements can be taken in combination with calcium rich foods or supplements to increase the efficiency of calcium absorption (NYU Langone Health, n.d.).

Lastly, a healthy and physically active lifestyle is highly recommended for someone with osteoporosis, especially exercises involving the use of small weight. Some examples of exercises individuals can partake in are dancing, walking, jump rope, hiking, and stair climbing. These exercises can aid in increasing bone strength and stimulating bone growth. In addition, health practitioners recommend that individuals suffering from osteoporosis should avoid smoking and consume no more than two alcoholic drinks per day as both decrease bone density and increase fracture risk (NYU Langone Health, n.d.).

Methods of Prevention

Beginning at a young age, it’s important to take steps to prevent osteoporosis. Some healthy practices/steps that can be taken include (“Osteoporosis”, 2017):

- Healthy diet incorporating whole grain, fruits, and vegetables

- No smoking

- Avoiding the act of smoking can help maintain bone density, as non-smokers often have greater bone mineral density in comparison to smokers.

- Reducing caffeine consumption

- Calcium absorption can be negatively affected by excessive caffeine consumption.

- Reducing alcohol consumption

- The risk of developing osteoporosis can increase by drinking excessive amounts of alcohol. For this reason, alcohol consumption should be limited.

- Adequate intake of vitamin D

- Vitamin D is naturally obtained from sun exposure, but there are limits to intake as too much exposure to the sun is not safe. Vitamin D from sun exposure is also limited depending on geographical location, or an individuals skin type. However, Vitamin D aids in the absorption of calcium though diet, which is why it’s important to consume foods that have some quantity of Vitamin D, even if it’s a small amount. Some of these foods include eggs or fatty fish such as salmon. Vitamin D supplements can also be taken, as foods containing Vitamin D are often not enough to achieve the recommended intake.

- Eating food that’s rich in calcium

- Maintaining a diet rich in calc * Unordered List Itemium is vital to preserve bone density. This will ensure that the body is receiving calcium from the blood, rather than taking it away from bones, which will affect bone density. Some foods that are high in calcium include dairy products, almonds, spinach, and sardines. Calcium supplements are also an option if this is unattainable through diet.

- The recommended calcium intake for different age groups is:

- Children: 1,300 mg

- Adults: 1,000 mg

- Men or women over the age of 70: 1,300 mg

- Strength training and/or weight-bearing exercises

- Exercises that are weight bearing can help improve balance and reduce the likelihood of falls. Weight bearing exercises include dancing, jogging, walking or any activity that requires movement on your feet. Exercises that are not weight bearing include cycling or swimming. Strength (or resistance) training is also beneficial for bone health as they can help maintain bone mineral density. Muscle strength can also help with balance, posture, and coordination.

Drugs and Medication

Osteoporosis used to be considered a sign of aging that was inevitable but can now be treated and prevented (Khosla & Hofbauer, 2017). Seeking treatment is recommended for individuals with osteoporosis as it can reduce the risk of fractures by almost 70% (Khosla & Hofbauer, 2017). Treatment is dependent on each individuals fracture risk and bone mineral density. To maximize positive outcomes, various forms of treatment are available that can be used in conjunction with healthy lifestyle and diet changes.

Various treatment methods/drugs work to slow the naturally occurring process of bone loss by inhibiting osteoclast activity (Khosla & Hofbauer, 2017). These medications are considered antiresorptive:

- Bisphosphonates

- Examples: Alendronate, risedronate, ibandronate, zoledronic acid (Khosla & Hofbauer, 2017)

- Disadvantage: this drug can have rare side effects such as bone tissue death in the jaw area, atypical femur fractures, and atrial fibrillation (Khosla & Shane, 2016)

- They are taken orally and are usually the first line of treatment. However they require users to take a break from treatment after 3-5 years of use to limit the risk of adverse effects (Khosla & Hofbauer, 2017)

- Selective oestrogen receptor modulators (SERMs)

- Raloxifene (Khosla & Hofbauer, 2017)

- Denosumab (Curtis, Moon, Dennison, Harvey, & Cooper, 2015)

- Strontium ranelate (Curtis et al., 2015)

There are also treatments that aid in bone formation, which are considered anabolic medications:

- Teriparatide

- Analogous to parathyroid hormone (PTH) which activates a pathway that is important to reduce the activation, proliferation, and maturation of osteoclasts (Khosla & Hofbauer, 2017)

- Treatment should be followed by the use of an antiresorptive to maintain bone density

Conclusion

Although there are treatments available and preventative measures that can be taken, osteoporosis is still prevalent worldwide with severe health implications. With the course of aging, this condition results in significant bone loss that makes those at risk more susceptible to fractures and other negative health outcomes. There are treatment options available to help maintain or increase bone mineral density, while reducing the risk of fracture by minimizing bone loss. However, many of the most common forms of treatment can be associated with adverse side effects following prolonged use. Further research is required to determine more effective forms of treatment or therapy that would be beneficial in treating patients long-term, as well as minimizing side effects.

References

Christodoulou, C., & Cooper, C. (2003). What is osteoporosis?. Postgraduate medical journal, 79(929), 133-138.

Grant, S. (2015). November is Osteoporosis Month. Retrieved March 5, 2019, from http://www.proofofcare.com/2015/11/november-is-osteoporosis-month/

Iqbal, M. M. (2000). Osteoporosis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Southern Medical Journal, 93(1), 2–18. Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10653058

Larsen, E. R., Mosekilde, L., & Foldspang, A. (2003). Vitamin D and Calcium Supplementation Prevents Osteoporotic Fractures in Elderly Community Dwelling Residents: A Pragmatic Population-Based 3-Year Intervention Study. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 19(3), 370–378. https://doi.org/10.1359/JBMR.0301240

Melton, L. J. (2001). The Prevalence of Osteoporosis: Gender and Racial Comparison. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00223-001-1043-9 Schettler, A. E., & Gustafson, E. M. (2004). Osteoporosis Prevention Starts in Adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 16(7), 274–282. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2004.tb00450.x

Minnis, G. (2016). Osteopeorosis Symptoms: Early and Late Stages. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/osteoporosis-symptoms#complications

Morrison, W. (2016). Osteoporosis Causes: Remodeling, Balance, and Hormones. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/osteoporosis-causes