Table of Contents

Sneezing

A sneeze, also known as a sternutation, is a defense mechanism for the human body to protect the airway of the respiratory system. It is a sudden, forceful, involuntary expulsion of air from the lungs through the nose and mouth caused by foreign particles irritating the mucous membranes of the nose or throat. Sneezing is the body's way of clearing irritants from the nose or throat. It can be provoked by a variety of things, including allergens, microbes, nasal irritants, inhalation of corticosteroids through a nasal spray, and drug withdrawal (“Everything You Need to Know About Sneezing”, 2019). This page will discuss the biological and pathophysiological aspects of the sneezing, severe implications of sneeze and its treatment methods, and a case study describing the implications, symptoms, and treatments on an individual who attempted to hold his sneeze.

Pathophysiology

Nose

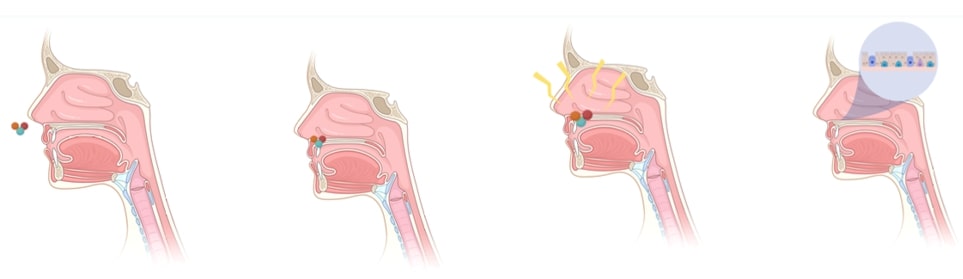

The human body is trained to fight intruders and maintain a healthy internal system. Sneezing is a protective reflex. Foreign particles such as bacteria, dirt, dust, smoke, perfumes or other irritate the respiratory epithelium lining of the nose and trigger the immune system. A signal is sent out to release chemicals known as histamine and leukotriene (Scientific American, 2000)]. These substances are manufactured by inflammatory cells such as eosinophils and mast cells typically found within the nasal mucosa. Histamine travels to the site of irritation, in this case the nose, and binds with special receptors to produce inflammation or increased mucus production (Söldner, Horn, & Sticht, 2018). Allergic reactions with the nasal mucosa require the presence of IgE (allergy antibody specific for the allergen). This leads to fluid leakage from vessels in the nose, causing symptoms of congestion and nasal drip.

The human body is trained to fight intruders and maintain a healthy internal system. Sneezing is a protective reflex. Foreign particles such as bacteria, dirt, dust, smoke, perfumes or other irritate the respiratory epithelium lining of the nose and trigger the immune system. A signal is sent out to release chemicals known as histamine and leukotriene (Scientific American, 2000)]. These substances are manufactured by inflammatory cells such as eosinophils and mast cells typically found within the nasal mucosa. Histamine travels to the site of irritation, in this case the nose, and binds with special receptors to produce inflammation or increased mucus production (Söldner, Horn, & Sticht, 2018). Allergic reactions with the nasal mucosa require the presence of IgE (allergy antibody specific for the allergen). This leads to fluid leakage from vessels in the nose, causing symptoms of congestion and nasal drip.

Brain

The nerves then transmit a signal to the medulla, also known as the ‘brain’s sneeze center’, where the sneeze reflex is triggered (Seijo-Martinez, 2006). This is why when we are sleeping we are unable to sneeze, given that the neurotransmitters that are signalled to the medulla are inactive.

Head & Neck

The nervous impulse travels up the sensory nerves and down the nerves controlling muscles in the head to go back and the neck to extend, leading to the rapid expulsion of air.

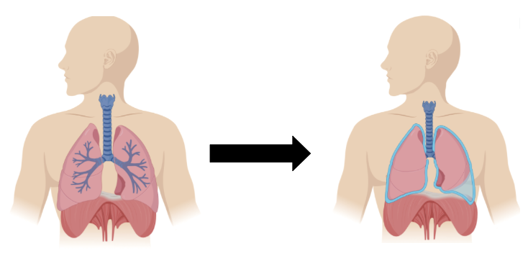

Abdominal & Chest

The abdominal and chest muscles are then activated, compressing the lungs to produce a blast of air (WebMD, n.d.).

The abdominal and chest muscles are then activated, compressing the lungs to produce a blast of air (WebMD, n.d.).

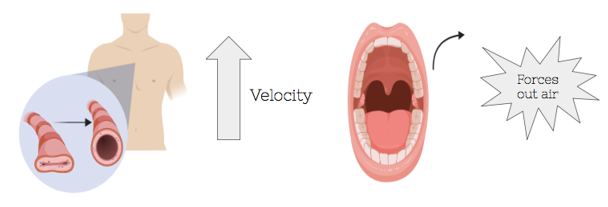

Tongue & Vocal Cords

The high velocity of the airflow is achieved by the buildup of pressure inside the chest and with the vocal cords closed. The sudden opening of the cords allows the pressurized air to flow back up the respiratory tract to expel the irritants. This helps to remove offending particles in the nose. The back of the tongue is elevated to force the air out of the mouth and nose (WebMD, n.d.). However, in infected individuals, it also allows for the spread of the common cold, as innumerable viral particles are contained within each droplet of mucus expelled. Germs from a sneeze can travel up to 6 feet (CDC, n.d.).

The high velocity of the airflow is achieved by the buildup of pressure inside the chest and with the vocal cords closed. The sudden opening of the cords allows the pressurized air to flow back up the respiratory tract to expel the irritants. This helps to remove offending particles in the nose. The back of the tongue is elevated to force the air out of the mouth and nose (WebMD, n.d.). However, in infected individuals, it also allows for the spread of the common cold, as innumerable viral particles are contained within each droplet of mucus expelled. Germs from a sneeze can travel up to 6 feet (CDC, n.d.).

Eyes

The split second the air is being forced out, the cranial nerves link both the eyes and the nose to the brain. Therefore, the stimulus also triggers the eyelid muscles to locked shut, making it impossible to keep eyes open while sneezing (WebMD, n.d.).

The split second the air is being forced out, the cranial nerves link both the eyes and the nose to the brain. Therefore, the stimulus also triggers the eyelid muscles to locked shut, making it impossible to keep eyes open while sneezing (WebMD, n.d.).

Heart

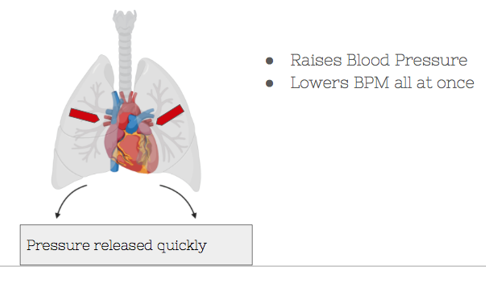

The moment a sneeze occurs, all the pressure built up in the abdomen gets released quickly. This increases the blood flow back to the heart, raises blood pressure, and lowers the BPM all at once.

The moment a sneeze occurs, all the pressure built up in the abdomen gets released quickly. This increases the blood flow back to the heart, raises blood pressure, and lowers the BPM all at once.

Sneezing Triggers

PSR (Photic Sneeze Reflux) or ACHOO (autosomal dominant compulsive helio-ophthalmic outbursts of sneezing) syndrome is when sneezing is induced by bright light. PSR occurs in 18 to 35 percent of the population and is genetic by nature (Scientific American, 2002).

Normal sneezing occurs due to irritation in the nasal cavity, while the photic sneezes occur due to irritation in the ocular cavity.

Potential consequences:

It can be dangerous for those with PSR when driving (going from a dim tunnel to the bright light).

Severe Implications of Sneezing

Because of the rarity of sneeze-related injuries, there is no recorded incidence. However, between 1948 - 2018 there have been 52 unique reports of sneezing-related injuries (Setzen & Platt, 2019). Of the cases reported 30% of the individuals had risk factors (Comorbidity) (Roselle & Herman, 2010) and 81% were males.

There are three causes/risk factors commonly associated with injury:

- Valsalva Maneuver - When the airways are voluntarily closed, and the pressure created by expiration is redirected towards soft tissue, injuries can occur. Because of the closed airway, this redirected pressure becomes 20x greater than a normal sneeze (Rahiminejad et al., 2016).

- Comorbidity - Makes an individual susceptible at the site of injury. Examples include trauma and infection.

- Gender - Increased lung size and therefore pressure during expiration makes males more at risk for injury.

Injuries can be divided into six areas: 1) Thoracic cavity, 2) Throat, 3) Ears, 4) Eyes, 5) Intracranium, 6) Other. The region with the most unique number of cases are the eyes (27%) (Ababneh, 2013) and the least are the ears (6%) (Comacchio & Mion, 2018).

Examples of injuries from the six regions include Rib Fractures, Laryngeal Fracture, Orbital Emphysema, Transient Ischaemic Attack, Vertigo, and Acute Myocardial Infarction (Setzen & Platt, 2019). Notable individuals with reported injuries as a result of sneezing include former Blue Jay player Kevin Pillar, baseball HOFer Sammy Sosa, and actor Billy Crystal.

Treatments

Non-pharmacological treatments:

Below are non-pharmacological treatments and ways to stop sneezing.

1) Treating allergies

Allergy sneezes can often occur in bursts of two to three. Therefore, treating allergies is one of the appropriate methods to prevent sneezing. In order to treat allergies, one needs to identify the allergens which trigger the allergic reaction (“How to Stop Sneezing: 10 Natural Remedies”, 2020) . Once identified, the person might be able to avoid the allergens and the resulting sneezing. Additionally, there are over-the-counter medications that assist with mitigating allergic symptoms, including antihistamine tablets and glucocorticosteroid nasal spray. However, in case of experiencing a more severe allergic reaction, prescription medications and allergy shots may be required to prevent or reduce the symptoms.

2) Treating photic sneezing

Photic sneezing is triggered as a person looks directly at bright lights, especially to the sun. Research indicates that about one-third of individuals are triggered to sneeze by looking to the bright lights globally (“How to stop sneezing: 12 natural tips”, 2020). People with photic sneezing can prevent multiple sneezes by simply not looking directly at bright lights such as sun and wearing sunglasses during sunny days, avoiding direct exposure to sunlight.

3) Consuming black cardamom

There are several health benefits of consuming black cardamoms; chewing two to three times a day helps to prevent multiple continuous sneezes. Additionally, research has shown that the black cardamom oil assists with normalizing mucus flow through the respiratory tract (“How to stop sneezing: 12 natural tips”, 2020).

4) Increasing vitamin C intake and drinking chamomile tea

Both vitamin C and chamomile are known to have an anti-histamine effect leading to the enhancement of the immune system. Therefore, by increasing the amount of vitamin C and drinking chamomile tea, a person can prevent sneezing via the reduction of the total amount of histamine in the body (“These natural home remedies can help you stop sneezing”, 2020). It is worth to mention that citrus fruits such as oranges, lemons, and grapefruits stores chemicals called flavonoids, that are significant antioxidant helping in empowering immune systems and thus assisting the human body in combating with microbes causing cold and other allergies which as a result leads to various symptoms including sneezing (“These natural home remedies can help you stop sneezing”, 2020).

Pharmaceutical Treatments:

Both allergic rhinitis (hay fever) and nonallergic rhinitis (vasomotor rhinitis) have similar symptoms, including chronic sneezing, congestion, and runny nose (“Nonallergic rhinitis”, 2019). However, there is no sign and evidence of an allergic reaction present in a person who was diagnosed with nonallergic rhinitis. Although there is little research on the exact cause of nonallergic rhinitis. Some common triggers include weather changes, environmental irritants such as dust and smog, and certain medications (Chang, 2018).

Common medications to reduce allergen-induced sneezes and allergic rhinitis are (Pathak, 2019): diphenhydramine (Benadryl) Loratadine (Claritin) Cetirizine (Zyrtec) Fexofenadine (Allegra) These pharmaceutical treatments and medications are known as antihistamines targeting histamine, which the body significantly produces during the allergic reaction.

Medications for non-allergic sneezes and nonallergic rhinitis include (“Nonallergic rhinitis”, 2019): azelastine (Astelin), Olopatadine (Patanase), and Nasal glucocorticoids.

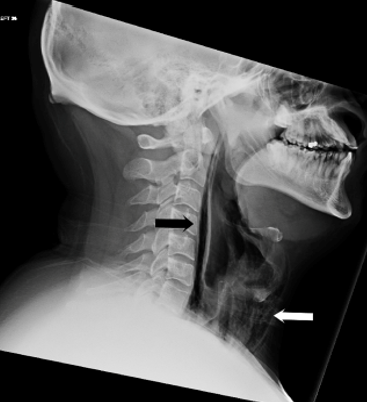

Case Study: Holding in A Sneeze

A healthy 34-year-old man presented to the hospital with odynophagia (pain when he swallowed) and a change to his voice after attempting to hold in his sneeze by holding his nose and mouth shut (Yang, Sahota, & Das, 2018). Due to the unusual nature of this condition, doctors had difficulty diagnosing the patient. Physical examination of his throat revealed that there was extreme swelling and tenderness concluding that he had ruptured the back of the throat. Doctors claimed to hear popping and crackling noises, extending from his neck to his ribcage (Yang, Sahota, & Das, 2018). The patient had no previous history of respiratory illnesses and denied swallowing anything sharp (Yang, Sahota, & Das, 2018). Upon admission, vital signs were taken and presented as stable with no fever. Several tests were completed hereafter. A laryngoscopy test showed normal functioning of the vocal cords. A CT taken of the neck showed streaks of air in the retropharyngeal region (Yang, Sahota, & Das, 2018). From this, doctors concluded that the air buildup and emphysema was a result of a pharyngeal tear after holding in the sneeze. The air collection was also the reason for the popping and crackling noises heard previously. The patient was diagnosed with spontaneous perforation of the pharynx similarly seen in those with blunt neck trauma (Yang, Sahota, & Das, 2018).

As this was an unusual case, the patient was treated with prophylactic intravenous antibiotics until the pain and swelling had gone down. The patient was fed via a nasogastric tube. After 7 days of admission, the patient’s emphysema had decreased and the nasogastric tube was removed (Yang, Sahota, & Das, 2018). The patient was given a soft-food diet. The patient was discharged and prescribed with advice on avoiding blocking the nose and covering the mouth when having to sneeze. After a two-month follow-up, the patient presented healthy, with no complications (Yang, Sahota, & Das, 2018).

From this case, it is important to take away that holding in a sneeze can cause serious complications. Though the patient was able to recover in a short period with minimal complications, in extreme cases, severe complications can arise from a pharynx rupture including respiratory failure, shock, sepsis, cerebral aneurysm, and potentially death (Yang, Sahota, & Das, 2018).

Presentation

https://docs.google.com/presentation/d/1NeYr9VY3Mte07KUEAX_N1hVM7J3lQT-iz5oZzaPqLws/edit?usp=sharing

References

Ababneh, O. (2013). Orbital, subconjunctival, and subcutaneous emphysema after an orbital floor fracture. Clinical Ophthalmology, 1077. doi: 10.2147/opth.s44649

Amin, S. (2019). The Potential Dangers of Holding in a Sneeze . Healthline. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/holding-in-a-sneeze#can-it-cause-a-heart-attack

Compare Current Sneezing Drugs and Medications with Ratings & Reviews. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/drugs/2/condition-3174/sneezing

Comacchio, F., & Mion, M. (2018). Sneezing and Perilymphatic Fistula of the Round Window: Case Report and Systematic Review of the Literature. The Journal of International Advanced Otology, 106–111. doi: 10.5152/iao.2018.4336

Chang, L. (2018, June 7). Nonallergic Rhinitis: Common Causes & Treatments. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/allergies/nonallergic-rhinitis#1

Do Your Part to Slow the Spread of Flu. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nonpharmaceutical-interventions/pdf/do-your-part-slow-spread-flutem5.pdf

Everything You Need to Know About Sneezing. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/sneezing

Fletcher, J. (2018, March 24). How to stop sneezing: 12 natural tips. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321305.php#12-ways-to-stop-sneezing

How to Stop Sneezing: 10 Natural Remedies. (2020). Retrieved 30 January 2020, from https://www.healthline.com/health/how-to-stop-sneezing

Nonallergic rhinitis. (2019, January 23). Retrieved from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/nonallergic-rhinitis/symptoms-causes/syc-20351229

Pathak, N. (2019, April 10). Allergy Relief: Which is Best: Antihistamines or Decongestants? Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/allergies/antihistamines-1

Roselle, H. A., & Herman, M. (2010). A hearty sneeze. The Lancet, 376(9755), 1872. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(10)61161-0

Rahiminejad, M., Haghighi, A., Dastan, A., Abouali, O., Farid, M., & Ahmadi, G. (2016). Computer simulations of pressure and velocity fields in a human upper airway during sneezing. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 71, 115–127. doi:10.1016/j.compbiomed.2016.01.022

Seijo-Martinez, M. (2006). Sneeze related area in the medulla: localisation of the human sneezing centre? Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 77(4), 559–561. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2005.068601

Setzen, S., & Platt, M. (2019). The Dangers of Sneezing: A Review of Injuries. American Journal of Rhinology & Allergy, 33(3), 331–337. doi: 10.1177/1945892418823147

Sneeze Video: What Happens to Your Body. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/allergies/allergy-education-17/video-anatomy-of-a-sneeze

Söldner, C. A., Horn, A. H. C., & Sticht, H. (2018). Binding of histamine to the H1 receptor—a molecular dynamics study. Journal of Molecular Modeling, 24(12). doi:10.1007/s00894-018-3873-7

Songu, M., & Cingi, C. (2009). Sneeze reflex: facts and fiction. Therapeutic Advances in Respiratory Disease, 3(3), 131–141. doi: 10.1177/1753465809340571

Why does bright light cause some people to sneeze? (2002, November 18). Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-does-bright-light-cau/

Why do we sneeze? (2000, April 17). Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-do-we-sneeze/

Yang, W., Sahota, R. S., & Das, S. (2018). Snap, crackle and pop: when sneezing leads to crackling in the neck. BMJ Case Reports. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2016-218906