This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Plaque Psoriasis

Presentation 3: Plaque Psoriasis Powerpoint File

<br>

Introduction

<style justify>TEXT</style>

<br>

Epidemiology

<style justify>TEXT</style>

<br>

Signs and Symptoms

Figure: A typical psoriatic plaque

Image from: http://www.wikipedia.com

Figure: A red and scaly scalp lesion

Image from: http://nopsoriasis.net </style>

<style justify> Common Symptoms

Plaque psoriasis is characterized by a few main symptoms. First and foremost are the plaques, or skin lesions, themselves. These lesions are often red or silvery in colour, inflamed, scaly or dry, and generally sore or itchy (WebMD, 2017). Plaques are hyperproliferated skin cells on the epidermal layer, and is attributed to premature maturation of keratinocytes and dermal inflammatory cells. These comprise of dendritic cells, macrophages and T cells (Palfreeman et al., 2013). These skin cells with reproduce very quickly, and build up, eventually shedding in scales and patches. These patches are the most visible and obvious symptom of psoriasis, regardless of the type. Psoriasis sufferers are also afflicted by skin soreness, itchiness, and can even report a sensation of burning in the affected areas. For plaque psoriasis sufferers, approximately 50% may also experience scalp plaques (Healthline, 2017). These are similar in look to the bodily plaques.

The location of plaques will change as the affected lesions begin to heal (Healthline, 2017). Newer patches may appear in different locations during future bouts. The symptoms of plaque psoriasis affect every sufferer differently, and no two people will experience exactly the same symptoms and plaque physiology.

The ‘Plaque’ in Plaque Psoriasis

The characteristic skin lesions of psoriasis take the form of raised plaques with silvery scales that can present on any part of the skin. The lesions usually begin as erythematous papules, and then tend to extend peripherally, eventually coalescing to form plaques (Raychaudhuri et al., 2014). However, in plaque psoriasis, the most common areas of the body that are afflicted are the scalp, back, and the extensor surfaces like knees and elbows (Palfreeman et al., 2013). Distribution of plaques on the body is generally random, and it varies greatly from patient to patient. Some may experience large coverage of the body in lesions, some may experiences plaques no larger than a dime.

New lesions can form at random, but also occur when the skin receives direct cutaneous trauma, and this is known as the Koebner phenomenon. Plaque psoriasis sufferers also experience the Auspitz phenomenon, where pinpoint bleeding occurs following a mild disruption of the superficial layer of the lesion. Plaque psoriasis is a chronic disorder, and reappearance of lesions do not necessarily occur in the same spots every time. Also, unlike inverse psoriasis, plaque psoriasis also does not afflict the genitals or armpits. </style>

<br>

Diagnosis

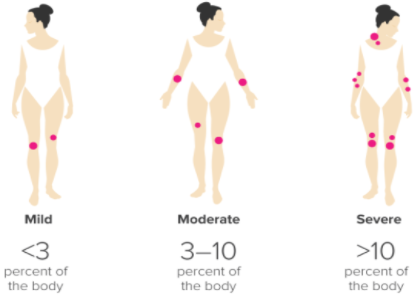

Figure: Ranking the severity of psoriasis, via PASI

Image from: http://www.healthline.com </style>

<style justify> Currently, there is no set diagnostic criteria for psoriasis, and so diagnosis is made clinically through pattern recognition and a detailed morphologic evaluation of skin lesions. Based on the morphology of the lesions and locations of plaques, psoriasis has been classified into various clinical phenotypes (Raychaudhuri et al., 2014).

In this way, the simplest and most accurate way to get an accurate diagnosis of psoriasis is simply to go to the dermatologist and have the doctor assess the lesions on the affected skin. More often than not, dermatologists are very well versed in the symptomatic characteristics of psoriasis and can quickly give a visual diagnosis without the need for blood sampling or extensive testing (WebMD, 2017).

A frequent issue with visual diagnosis of psoriasis is that physiologically, this condition is very similar in look to the presentation of eczema. Patches of plaque psoriasis and eczema share the characteristics of redness, scaliness, and inflammation, making them hard to distinguish from one another (WebMD, 2017). However, psoriasis is usually also accompanied by silvery scaling as well as red. This is because psoriasis is a chronic autoimmune condition that results in the overproduction of skin cells and these dead cells build up into silvery-white scales. Eczema is typically not covered in this dead skin, as it inflammation, and not an immune compromised skin disorder. This is one key feature that can distinguish the two. Yet, sometimes psoriasis does not produce this silvery covering and can still be hard to distinguish from eczema.

When cases like this are more difficult, a skin biopsy can also be used to give a more accurate diagnosis (WebMD, 2017). In a skin biopsy, a small sample of affected skin is taken from a patient and observed under the microscope. The dermatologist will look for clubbed epidermal projections or epidermal thickening as characteristics of psoriasis lesions (Raychaudhuri et al., 2014). This technique can be used when a diagnosis is more difficult, like in the comparison to eczema, or in atypical cases (Healthline, 2017).

The clinical phenotypes of psoriasis have been classified based on factors such as age of onset, degree of skin involvement, morphologic pattern and predominant involvement of specific anatomic location of the body (Raychaudhuri et al., 2014).

Dermatologists can also rank the severity of the condition based on the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, or PASI. This scale allows the doctor to rank the severity of the condition based on how much surface area of the skin is covered in lesions (Healthline, 2017). Less than 3% boyd coverage of plaques is considered ‘mild’, 3-10% is ‘moderate’, and anything over 10% is considered ‘severe’. This is largely at the discretion of the physician. The assessment is made by assigning an ascending score to plaque severity in terms of thickness, redness, and scaling, and the extent of the plaque spread (Healthline, 2017). </style>

<br>

Etiology

<style justify>The etiology of this disease is unclear, as there is no definite cause. This is considered to be a multifactorial disease, which means that it is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

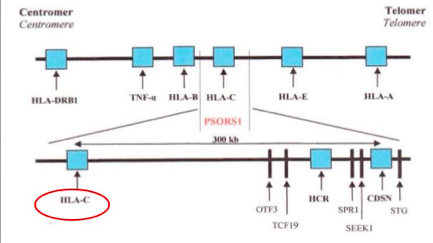

The idea of psoriasis having a genetic basis has been accepted in the medical community for many years now. However, not all the genes that are associated with this disease have yet been identified, through the general region of these genes is known (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007). Specifically, one locus that has been identified in psoriasis is the class 1 region of the major histocompatibility locus antigen cluster (MHC). There have been nine loci identified on different chromosomes that are associated with this disease, and they are named psoriasis susceptibility 1 through 9 (PSOR1 through PSOR9). These genes are located on pathways that lead to inflammation, and mutations of these genes lead to psoriasis (Nestle, Kaplan, & Barker, 2009). The most significant gene locus is PSORS-1, which is located on chromosome 6p2 in the MHC, though the specific gene has not yet been identified. This gene locus contains genes such as the HLA-C variant HLA-Cw6. This locus accounts for 35%-50% of the heritability of this disease (Smith & Barker, 2006). Interestingly, these loci are shared by other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, type1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and atopic dermatitis, which indicates that these complex inflammatory diseases have a similar root cause (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007). The MHC has a low penetrance of only about 10%; this suggests that other factors should also be considered in the etiology of this disease (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007). Another set of genes that have the ability to affect the immune system are those that are involved with keratinocyte differentiation. Specifically, variants in the SLC9A3R1/NAT9 region and loss of the RUNX binding site are factors that could affect regulation of the immune synapse (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007). Another gene pool to be considered is alleles that encode IL-12, IL-19/20, and IRF2, as these also play a role in the pathophysiology of psoriasis (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007).

There are also environmental factors at play which contribute to this disease. These include prolonged psychological stress and trauma and infections in the body (Smith & Barker, 2006). Another environmental trigger is changes in the climate (Smith & Barker, 2006). Certain medications and drugs may also induce psoriasis. Specifically, drug-induced psoriasis may occur with the use of medications such as beta blockers, lithium, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Jain, 2012) and TNF inhibitors (Guerra & Gisbert, 2013).

</style>

<br>

Pathophysiology

<style justify>TEXT</style>

<br>

Prognosis

<style justify>TEXT</style>

<br>

Treatment and Management

<style justify>TEXT</style>

<br>

References

Palfreeman, A. C., McNamee, K. E., & McCann, F. E. (2013). New developments in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a focus on apremilast. Drug Des Devel Ther, 7, 201-210.

“Plaque Psoriasis Pictures”. Healthline. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

“Psoriasis Symptoms and Triggers”. WebMD. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

Raychaudhuri, S. K., Maverakis, E., & Raychaudhuri, S. P. (2014). Diagnosis and classification of psoriasis. Autoimmunity reviews, 13(4), 490-495.

<br>