This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Adderall

Introduction

History of Adderall

Adderall is a prescribed medication that consists of a mixture of two different molecular structure of amphetamine. Amphetamine was first synthesized in 1887 by a Romanian chemist, Lazăr Edeleanu. The drug’s first pharmacological appearance was in 1934 as an inhaler for congestion under the trade name Benzedrine. It was not until World War II, the Allied and Axis forces discovered the performance-enhancing effect of the drug and began widely consumed by the soldiers to boost combat morale and concentration. The discovery of amphetamine’s stimulant properties widely expanded its applications, from focus enhancement drug to promoting its effects on weight loss. Pharmaceutical companies began to market the drug to the general public as a weight loss pill and even as a medication for depression (Rasmussen, 2008).

Figure 2. Image of soldiers during World War II (Nix, 2018)

Current Use of Adderall

Today, amphetamine is sold under the brand Adderall. It is commonly used as a treatment for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to increase focus and reduce impulsive behaviors. Adderall also showed effeteness in increasing daytime wakefulness for people with narcolepsy (WebMD, n.d.). However, the drug is not without consequences. Adderall contained a boxed warning from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), indicating a significant risk of serious or even life-threatening effects when consuming inappropriately. However, because of Adderall’s ability to improve attention and performance, people often abused the drug by using it as a performance and cognitive enhancer. Students and professionals use Adderall to help them stay awake and focus for a longer period of time in the face of ever-increasing demand from school and work (Juergens, 2019). Professional players in the eSport industry take Adderall to boost their concentration and help them perform better in tournaments (The Recovery Village, 2019). People also abuse Adderall for recreational purposes due to its stimulative and addictive properties. As a result, Adderall abuse is a prevalent issue in today’s society, and the public needs to be better educated about the drug to make an informed decision when considering it.

Figure 3. Image of professional eSport players (Itani, 2017)

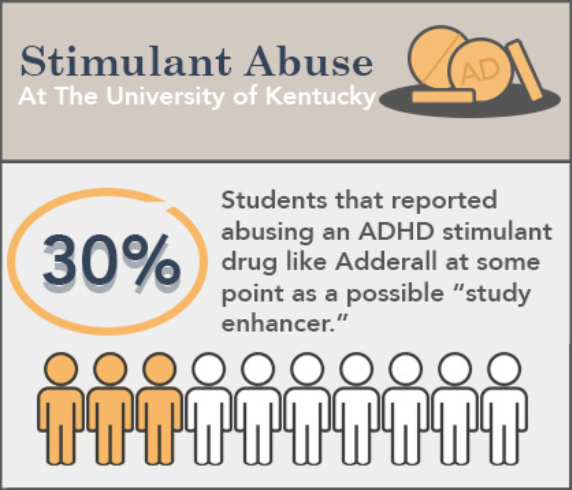

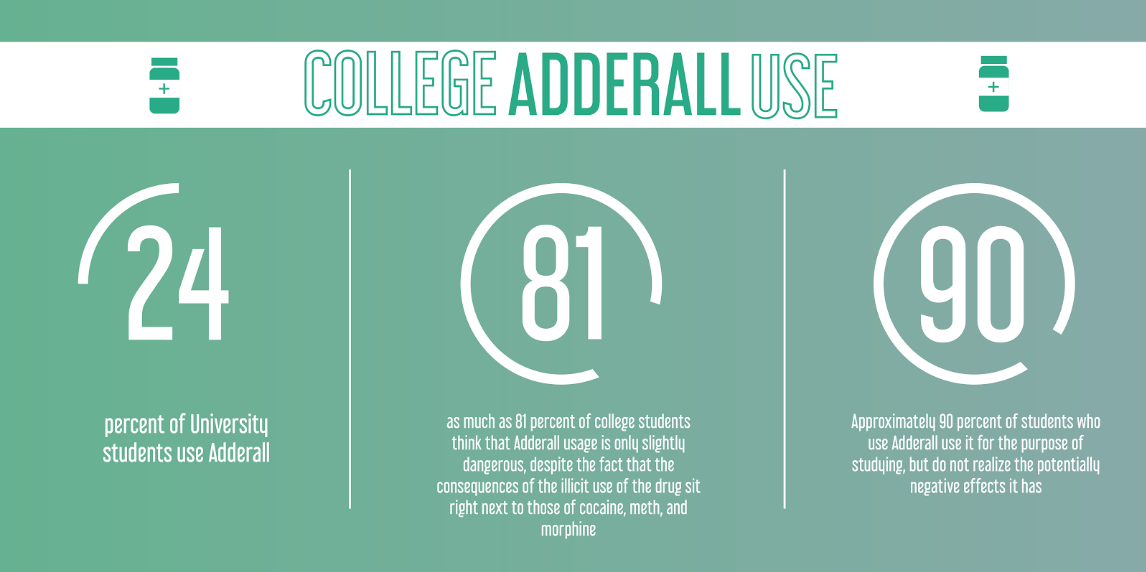

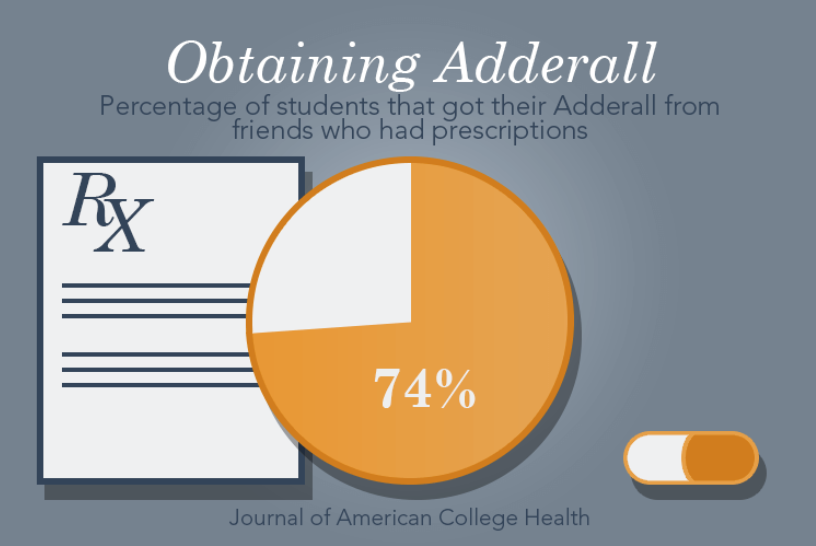

Statistics on the Use of Adderall by Students

The reliance on Adderall by students has been a concern for some time, especially due to the number of students who are unaware of the potential negative health impacts of Adderall abuse. The only legal method of obtaining Adderall is through prescription, however, many students continue to use Adderall illegally by borrowing them from someone they know, such as a friend.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is classified as a mental health condition in which an individual has difficulty paying attention, focusing on tasks, acts without thinking, and has trouble sitting still. ADHD is most commonly diagnosed between the ages of 6 and 12 via an intensive analysis of the child’s distractibility, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (Husney, 2018). The exact cause of ADHD is yet to be determined, but it is generally understood that both genetic and environmental factors play a role in the disruption of normal brain function and development.

Figure 7. Image of young students in class (CITATION NEEDED**)

ADHD has a mean worldwide prevalence of 2.2% of cases in all children and adolescents (younger than 18 years of age). The mean prevalence in adults in Asia, Europe, North and South America, and the Middle East is 2.5%. It has also been noted that ADHD is more often reported in males as compared to females (ADHD Institute, 2019).

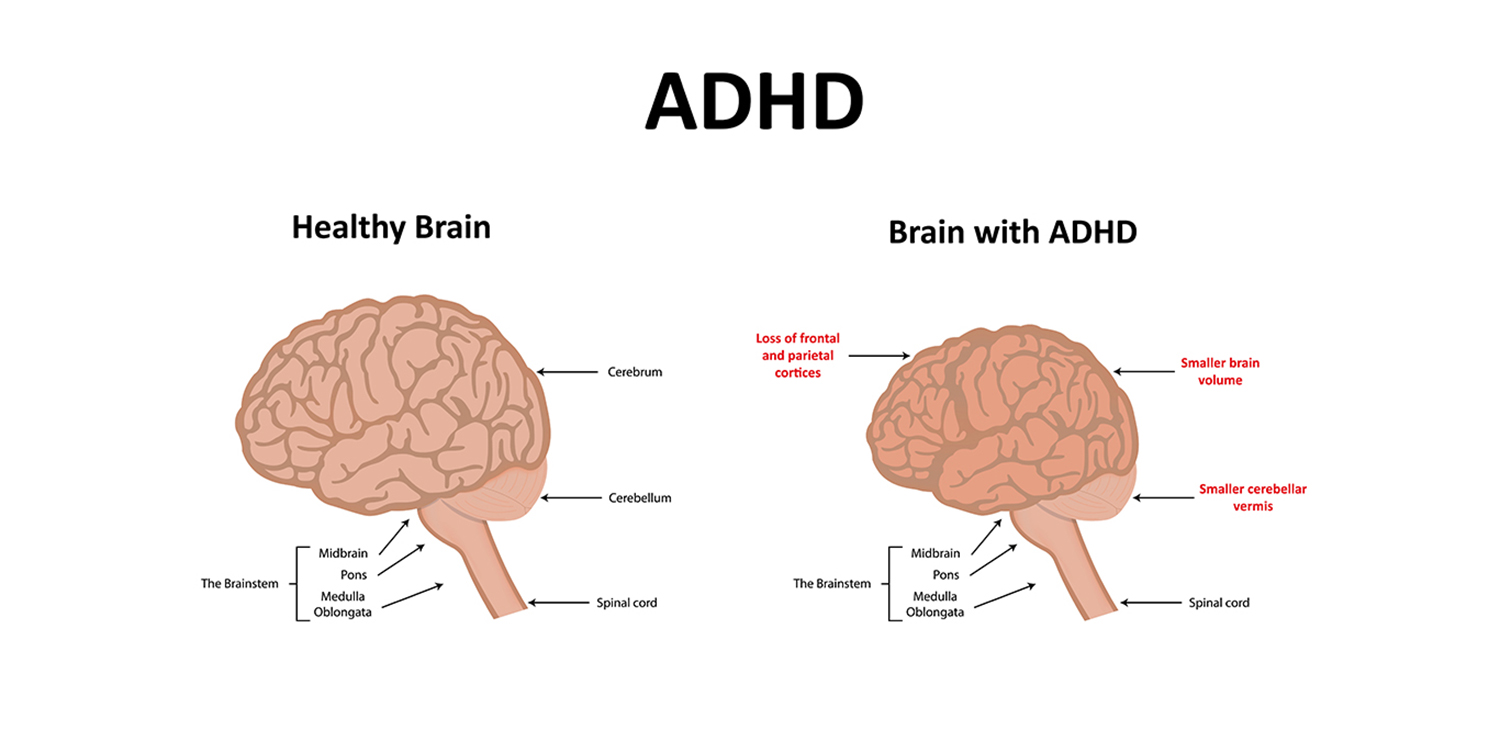

Previous studies on individuals with ADHD have demonstrated that parts of the ADHD brain mature at a much slower pace and do not reach the same level of maturity when compared to the brain of an individual who does not have ADHD (Hoogman et al, 2017). A previous 2010 study found that ADHD children do not have the same neural connections between the frontal cortex of the brain and the visual processing area, suggesting that the ADHD and non-ADHD brains process information differently (Mazaheri et al, 2010). Furthermore, the ADHD brain has shown an inability to regulate the homeostatic dopamine system. Such individuals are not able to produce enough dopamine and its complementary receptors, resulting in the dopamine in their brains unable to be efficiently utilized (Campo et al, 2011). Despite these noticeable differences in the brain, ADHD is not diagnosed with the use of a PET of fMRI scan because such screening tests are only able to provide information about how an individual’s brain is functioning at the moment of the test, whereas a clinical interview and behavioral questionnaire coordinated by a registered physician will take into account how the brain functions in different situations to allow for a more concrete diagnosis.

Figure 8. The difference between a healthy brain and a brain with ADHD (CITATION NEEDED**)

Due to the dysregulation of dopamine in the ADHD brain, stimulant medications are often used as treatments in order to promote increased levels of dopamine in the brain. One such stimulant in Adderall, with vast research in support of its ability to improve attention, focus, and reduce impulsive behavior. Between 75-80% of children see improved symptoms with the use of Adderall (Kolar et al, 2008).

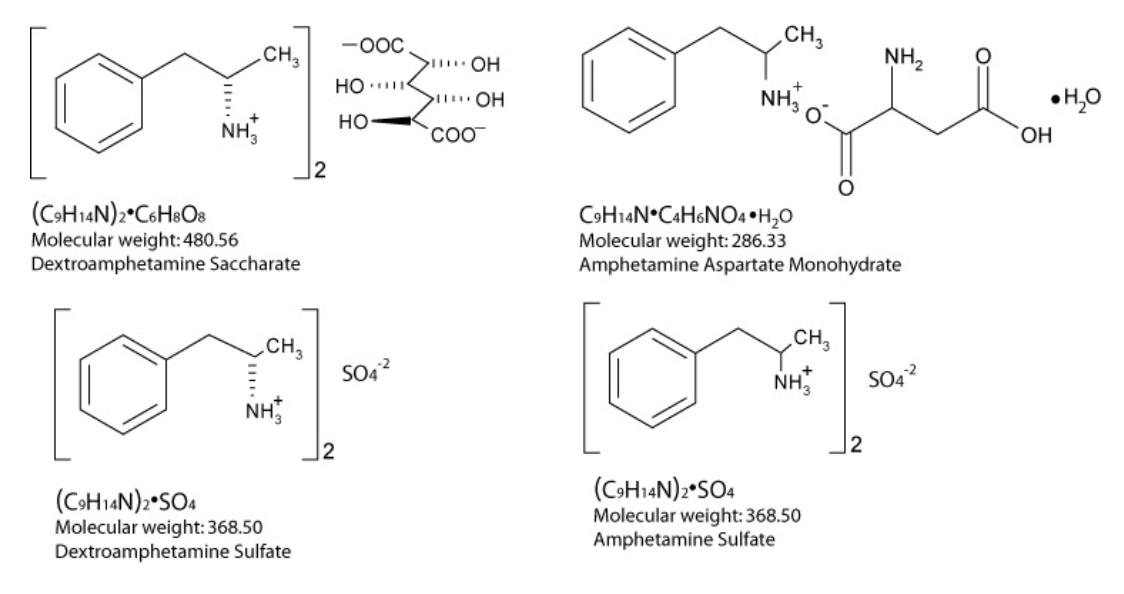

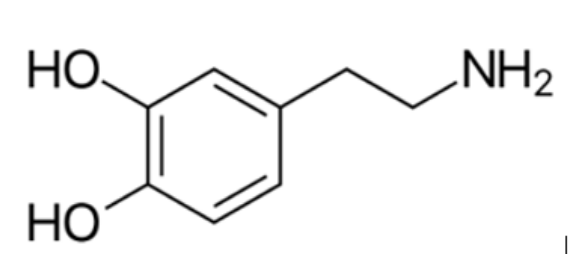

Mechanisms of Adderall

Adderall is taken orally, meaning it is initially absorbed by the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (Sherzada, 2012). The effects of Adderall are at maximum efficiency after 3 hours upon taking the drug (Sherzada, 2012). Adderall is made of small molecules known as amphetamines, that have the ability to overcome an obstacle for many types of molecules, being able to cross the blood-brain-barrier (BBB) (Sherzada, 2012). Being able to cross the BBB allows amphetamine’s effects to reach the central nervous system. Dextroamphetamine salts account for 75% of the salt content of Adderall, and levoamphetamine salts account for the other 25% (Sherzada, 2012). Dextroamphetamine targets the prefrontal cortex of the brain and increases levels of the neurotransmitter dopamine, whereas levoamphetamine targets the peripheral nervous system and increases levels of another neurotransmitter, norepinephrine (Sherzada, 2012).

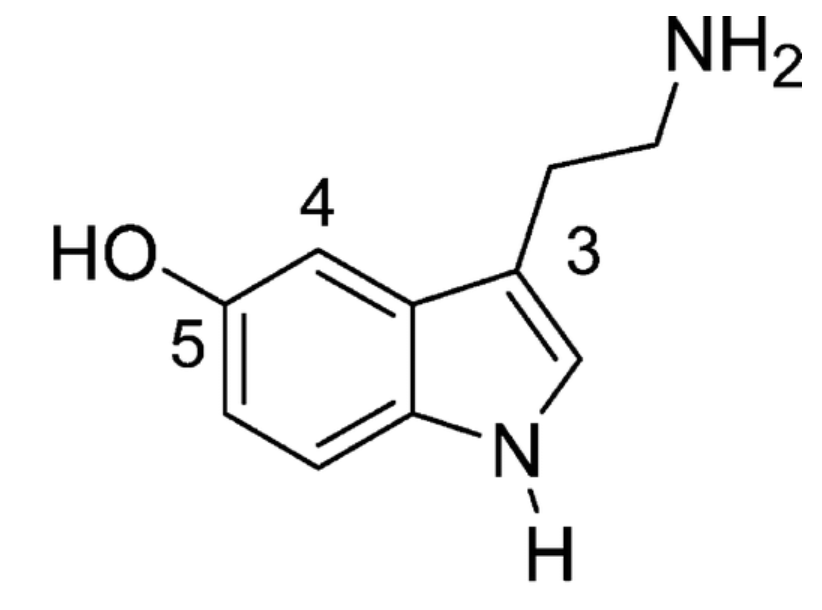

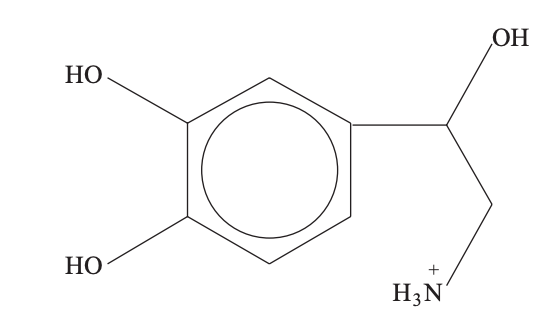

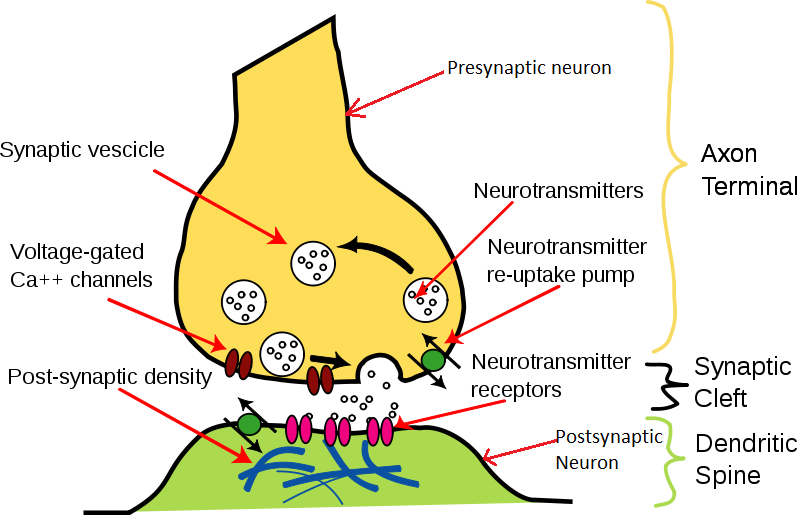

Although amphetamines such as dextroamphetamine are capable of increasing levels of dopamine, the mechanism by which this change occurs is relatively unknown (Freyberg et al., 2016). However, some mechanisms have been proposed for the regulation of dopamine levels. One example involves the interaction of amphetamines in vitro with the vesicular monoamine transporter (VMAT) (Freyberg et al., 2016). In this mechanism, amphetamines behave as non-substrate inhibitors that work to block the collection of dopamine into vesicles, thereby allowing more dopamine to exit rather than being stored (Freyberg et al., 2016). Neurotransmitters are chemicals that are released from presynaptic nerve terminals which serve as a communication tool by sending messages along cells to perform an action in the body, by using the power of action potentials (Rizo, 2018). The neurotransmitter dopamine is responsible for increasing levels of motivation and motor function (Wise, 2004). The associated increase in dopamine can induce a feeling of euphoria when stimulants are taken nonmedically (Varga, 2012). The neurotransmitter norepinephrine is responsible for increasing blood pressure and heart rate, which makes individuals feel more alert and energized (Strawn, Ekhator, Horn, Baker, & Geracioti Jr, 2004). Norepinephrine has also been shown to promote memory consolidation in the earlier stages of memorization (Murchison et al., 2004). The third neurotransmitter targeted by Adderall is serotonin, which promotes mood and can also help the body maintain a circadian rhythm, or waking up and sleeping at about the same time each day (Ursin, 2002).

The key mechanism of Adderall is to prevent neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine and also serotonin from being uptaken by the presynaptic neuron and instead be released into the synaptic space (Sherzada, 2012). This ultimately results in an increase in the levels of these neurotransmitters which work to reduce symptoms of ADHD, such as hyperactivity, impulsive actions and a minimized attention span (Sherzada, 2012). There are also enzymes in the body that work to inhibit the levels of these neurotransmitters by breaking them down, also known as monoamine oxidase (Sherzada, 2012). Amphetamine in Adderall can inhibit the action of this enzyme to maintain a high level of neurotransmitters in the body (Sherzada, 2012).

Side Effects of Adderall

Prescription

The study by Ahmann et al. (2001) looked at the efficacy and side effects of Adderall for young children with ADHD. They found that Adderall was effective and its side effect profile was consistent with other psychostimulants. Other studies also found that Adderall for children with ADHD had minimal side effects in the short and long term (Manos et al., 1999; Findlin et al., 2005).

Illicit/Recreational Use

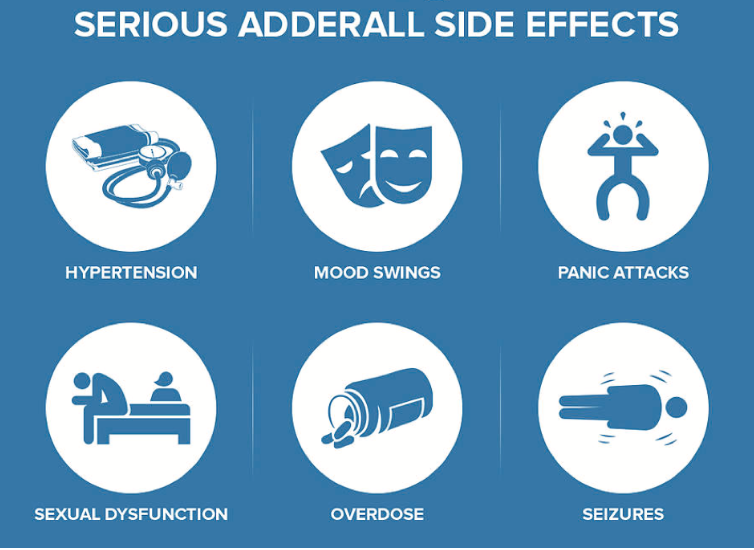

Short terms of Adderall abuse include gastrointestinal problems, blurred vision, increased body temperature, increased blood pressure, increased heart rate, reduced circulation, irritability, and insomnia. Long-term and excessive use of Adderall may result in hallucinations, psychotic episodes, cardiac arrest, a comatose state, or even death. Intense mood changes and physical and mental cravings are common symptoms long-term users can also experience. Furthermore, drug tolerance increases with continual use resulting in heightened physiological dependency, which intensifies the impact of withdrawal symptoms when usage ceases. Individuals entering withdrawal can experience violent mood swings, extreme fatigue, and uncontrollable cravings (Varga, 2012).

Clinical signs of Adderall overdose in humans include hyperactivity, hyperthermia, tachycardia, tachypnea, mydriasis, tremors, and seizures. Amphetamine and its analogues stimulate the release of norepinephrine affecting both α– and β–adrenergic receptor sites (Fitzgerald & Bronstein, 2013).

Addiction and Withdrawal

Adderall abusers are 20 times more likely to use cocaine and heroin once the body builds a tolerance for Adderall. Multiple studies have revealed associations between prescription drug abuse and higher rates of cigarette smoking; heavy episodic drinking; and marijuana, cocaine, and other illicit drug use (Volkow, 2005).

Over time, the body may become dependent on the drug to function normally. The withdrawal symptoms that could arise include tiredness, panic attacks, crankiness, extreme hunger, depression, and nightmares. These symptoms are psychological and stopping the drug suddenly can cause extreme fatigue and severe, even suicidal, depression in adult patients. Again, a person should never stop taking Adderall abruptly but should do so gradually (Sherzada, 2012).

Treatment of Adderall Abuse

Treatment involves two main approaches, medication-assisted treatment (MAT) and psychotherapy (American Addiction Centers, 2019). MAT uses medication to reduce the effect of symptoms and slowly weaning the patient off of Adderall. Treatment is directed at controlling life-threatening central nervous system and cardiovascular signs. Seizures can be controlled with benzodiazepines, phenothiazines, pentobarbital, and propofol. Cardiac tachyarrhythmias can be managed with a β-blocker such as propranolol. Intravenous fluids counter the hyperthermia, assist in the maintenance of renal function, and help promote the elimination of amphetamine and its analogues (Fitzgerald & Bronstein, 2013). Psychotherapy is used to maintain abstinence from Adderall through cognitive behavioral therapy (American Addiction Centers, 2019).

Case study - Adderall Addiction, Tolerance, Withdrawal from a University Sophomore

The use of Adderall has been increasing rapidly. In the 1990s, an estimated 3 to 5 percent of school-age American children were believed to have A.D.H.D., according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In 2012, roughly 16 million Adderall prescriptions were written for adults between the ages of 20 and 39. The medication was accessible nearly everywhere.

The twenty-first century was the century where the young adults, with or without ADHD, were on Adderall in the belief that it is an academic performing enhancer drug. The medication started to appear from close acquaintances distributing the medication to black markets. High-achieving, ambitious students may take Adderall, out of curiosity or desire to perform better at school. Unfortunately, Adderall is an addictive drug where individuals develop tolerance to the drug and unable to perform without it. The twenty-first century was soon coined the term “Adderall generation”.

An example of the student in the Adderall generation is Casey Schwartz, a typical undergraduate who went to Brown University. In her sophomore year, she once lamented to a friend the impossibility of her plight: she had a five-page paper due the next afternoon on a book she had only just begun reading. Her friend asked, “Do you want an Adderall?”

After taking the Adderall that her friend offered, Casey claimed that she was able to focus like never before, locking herself up in the basement of the library, being able to put two all-nighters in a row. She described this intense experience as “peerless ecstasy”. hunkered down in the Absolute Quiet Room, in a state of peerless ecstasy. However, as attractive her first experience with Adderall seemed, the addiction and dependence of Adderall seemed to grow a lot more. Casey claims that there would be days when she said it would be hard to keep track of how many pills of Adderall she has already taken. One day, when she was madly typing in the library (once again, powered by Adderall), she claimed that outside the window, the sky was turning pink. She would experience excitement and be able to experience higher self-esteem from her capability and the quality of the work that she would produce with Adderall. For this, she would go out of her way to get hands-on Adderall on campus, for 2 years. She was confident that with Adderall, she would never go back to the “lazier, glitchy self” and become the “indistractable, high-achieving” person she always wanted to be.

“Adderall wiped away the question of willpower. Now I could study all night, then run 10 miles, then breeze through that week’s New Yorker, all without pausing to consider whether I might prefer to chat with classmates or go to the movies. It was fantastic.”

Figure 16. Casey Schwartz, a staff writer at Newsweek/The Daily Beast, where she covered neuroscience, psychology, and psychiatry. Her writing has also appeared in The New York Times and The New York Sun (Schwartz, 2015).

Then, the good side of adderall stops here: Casey in the library realizes she has difficulties to breathe, accompanied by the bright room shining too bright and the light dilating around her. Casey was immediately taken to the emergency room and was diagnosed with: anxiety, adderall induced panic attack, a reaction induced by taking too much adderall (adderall overdose). Along with this, Casey was unable to sleep properly, with nights where she was “craving “ adderall, to the extent where one medication of the drug was not “suffice”. In other words, she has developed tolerance. Although she wanted to stop taking the drug after the emergency department incident, she admitted that it was difficult to not get her hands on it.

Figure 17. Quote by Casey Schwartz (Schwartz, 2016)

Martha Farah, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Pennsylvania, studied the effect of Adderall on subjects taking a host of standardized tests that measure restraint, memory and creativity. On balance, Farah and others have found very little to no improvement when their research subjects confront these tests on Adderall. Ultimately, she says, it is possible that “lower-performing people actually do improve on the drug, and higher-performing people show no improvement or actually get worse.” In fact, a study found that the average GPA of students taking Adderall to be 3.071, and for students not taking Adderall to be 3.267 (Girer, Sasu, Ayoola, & Fagan, 2011). Adderall complicates the usual dynamic of drug addiction by being squarely associated with productivity, achievement and success. It is very hard to go off it because it leads individuals to think that they will no longer be able to produce the great works they used to with adderall without it. Plenty of people are still able to do well when they go off adderall, but Dr. Farah claims that it is the fear in going off Adderall more than anything.

While Casey thought she was having total control over herself through Adderall, she realized that it was exactly the opposite: The Adderall made her life unpredictable.

“I was terrified I had done something irreversible to my brain, terrified that I was going to discover that I couldn’t write at all without my special pills.” - Casey

The following information has been obtained from: Casey Schwartz, a New York Times article in 2016.

Conclusion - Natural Remedies for ADHD Symptoms

There are many natural remedies to avoid Adderall or ADHD in general. Maintaining a healthy lifestyle can help minimize the symptoms of ADHD, and is an effective alternative for people without ADHD who resort to drugs such as Adderall to improve their focus, such as students. Essentially, students can work to enhance their ADHD by changing their lifestyle (Lakhan & Kirchgessner, 2012). Living a healthy life is not only beneficial for improving concentration and minimizing other ADHD symptoms, it is also beneficial for mental health and overall well-being.

Methods of naturally improving health:

- Eating a healthy, well-balanced diet

- Getting at least 60 minutes of exercise each day

- Getting plenty of sleep (e.g. 8 hours)

- Limiting daily screen time from phones, computers, and TV to improve sleep quality, have all been proven remedies.

Figure 18. Image of healthy food (Gunnars, 2019)

References

ADHD Epidemiology. (n.d.). ADHD Institute. Retrieved January 25, 2020, from http://adhd-institute.com/burden-of-adhd/epidemiology/

Ahmann, P. A., Theye, F. W., Berg, R., Linquist, A. J., Van Erem, A. J., & Campbell, L. R. (2001). Placebo-controlled evaluation of amphetamine mixture—dextroamphetamine salts and amphetamine salts (Adderall): efficacy rate and side effects. Pediatrics, 107(1), e10-e10.

American Addiction Centers. (2019). Adderall Addiction - From Abuse to Treatment. Retrieved from https://americanaddictioncenters.org/adderall

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). (n.d.). HealthLink BC. Retrieved January 25, 2020, from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/hw166083

Campo, N. del, Chamberlain, S. R., Sahakian, B. J., & Robbins, T. W. (2011). The Roles of Dopamine and Noradrenaline in the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 69(12), e145–e157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.02.036

Findling, R. L., Biederman, J., Wilens, T. E., Spencer, T. J., McGough, J. J., Lopez, F. A., & Tulloch, S. J. (2005). Short-and long-term cardiovascular effects of mixed amphetamine salts extended release in children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 147(3), 348-354.

Fitzgerald, K. T., & Bronstein, A. C. (2013). Adderall®(amphetamine-dextroamphetamine) toxicity. Topics in companion animal medicine, 28(1), 2-7.

Freyberg, Z., Sonders, M. S., Aguilar, J. I., Hiranita, T., Karam, C. S., Flores, J., … & Martin, C. A. (2016). Mechanisms of amphetamine action illuminated through optical monitoring of dopamine synaptic vesicles in Drosophila brain. Nature Communications, 7(1), 1-15.

Girer, N., Sasu, N., Ayoola, P., & Fagan, J. M. (2011). Adderall Usage Among College Students.

Gunnars, K. (2019). 50 Foods That Are Super Healthy. Healthline. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/nutrition/50-super-healthy-foods

Hoogman, M., Bralten, J., Hibar, D. P., Mennes, M., Zwiers, M. P., Schweren, L. S. J., Hulzen, K. J. E. van, Medland, S. E., Shumskaya, E., Jahanshad, N., Zeeuw, P. de, Szekely, E., Sudre, G., Wolfers, T., Onnink, A. M. H., Dammers, J. T., Mostert, J. C., Vives-Gilabert, Y., Kohls, G., … Franke, B. (2017). Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: A cross-sectional mega-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(4), 310–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30049-4

Itani, H. (2017). eSports: Are they here to stay? Retrieved from https://www.sotrender.com/blog/2017/06/esports-are-they-here-to-stay/?fbclid=IwAR3INtfXApN3Ml8DEOrkSm6xSAlPn14C4CleWaJvf8t_QoefeFOJ8BxpPXw

Kolar, D., Keller, A., Golfinopoulos, M., Cumyn, L., Syer, C., & Hechtman, L. (2008). Treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 4(2), 389–403.

Lakhan, S. E., & Kirchgessner, A. (2012). Prescription stimulants in individuals with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: misuse, cognitive impact, and adverse effects. Brain and Behavior, 2(5), 661–677. doi: 10.1002/brb3.78

Manos, M. J., Short, E. J., & Findling, R. L. (1999). Differential effectiveness of methylphenidate and Adderall® in school-age youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(7), 813-819.

Mazaheri, A., Coffey-Corina, S., Mangun, G. R., Bekker, E. M., Berry, A. S., & Corbett, B. A. (2010). Functional Disconnection of Frontal Cortex and Visual Cortex in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biological Psychiatry, 67(7), 617–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.022

Murchison, C. F., Zhang, X. Y., Zhang, W. P., Ouyang, M., Lee, A., & Thomas, S. A. (2004). A distinct role for norepinephrine in memory retrieval. Cell, 117(1), 131-143.

Nix, E. (2018). Why Were American Soldiers in WWI Called Doughboys? Retrieved from https://www.history.com/news/why-were-americans-who-served-in-world-war-i-called-doughboys?fbclid=IwAR12BxkBIEFC2kndsLK7DaFZk8AaQvtMY8rPisKb526225nq5nSA_IorBuI

Rasmussen, N. (2008). America’s First Amphetamine Epidemic 1929–1971. American Journal of Public Health, 98(6), 974–985. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2007.110593

Rizo, J. (2018). Mechanism of neurotransmitter release coming into focus. Protein Science, 27(8), 1364-1391.

Schwartz, C. (2015). 096: Casey Schwartz. Retrieved from https://www.oneyoufeed.net/casey-schwartz/

Schwartz, C. (2016). Generation Adderall. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/16/magazine/generation-adderall-addiction.html

Sherzada, A. (2012). An analysis of ADHD drugs: Ritalin and Adderall. JCCC Honors Journal, 3(1), 2.

Strawn, J. R., Ekhator, N. N., Horn, P. S., Baker, D. G., & Geracioti Jr, T. D. (2004). Blood pressure and cerebrospinal fluid norepinephrine in combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychosomatic Medicine, 66(5), 757-759.

The Recovery Village. (2020). Adderall. Retrieved from https://www.floridarehab.com/drugs/adderall/?fbclid=IwAR2hVjdPu_eQWjjC0s_dod60Uf1o6u_QxqT-kzrrH_9Zhwn7PTWmJCFyMfc

The Recovery Village. (2019). League of Amphetamines: Should Adderall Be Banned From eSports? Retrieved from https://www.therecoveryvillage.com/adderall-addiction/adderall-users-banned-esports/#gref

Ursin, R. (2002). Serotonin and sleep. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 6(1), 55-67.

Varga, M. D. (2012). Adderall abuse on college campuses: a comprehensive literature review. Journal of evidence-based social work, 9(3), 293-313.

Volkow, N. D. (2005). Prescription drugs: Abuse and addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse.

WebMD. (n.d.). Adderall Oral : Uses, Side Effects, Interactions, Pictures, Warnings & Dosing. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/g00/drugs/2/drug-63163/adderall-oral/details

Wise, R. A. (2004). Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 5(6), 483-494.