Table of Contents

herpes_simplex_virus_group_2.pdf

Herpes Simplex Virus

Herpes is an ancient Greek terminology meaning ‘creep’ or ‘crawl’, which represents a family viruses (Whitley & Roizman, 2001). The most common viruses within this family which infect humans are the Herpes Simplex Virus-1 (HSV-1) and Herpes Simplex Virus-2 (HSV-2).

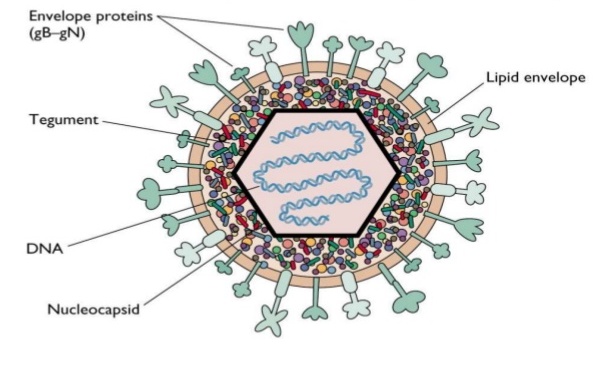

HSV contains double-stranded DNA in the core of the virion (Whitley & Roizman, 2001). Superficial to the core is the icosapentahedral capsid, surrounded by an amorphous layer of protein called tegument. Like many other viruses, the HSV has a lipid envelope at the most outer layer. The envelope of the virus contains many different surface proteins which bind to the cell-surface receptor, and through this mechanism they are able to initiate the infection.

Epidemiology

A serology study, which involves measuring a type of pathology within a population through analyzing their serum, was conducted in Ontario, Canada. This study aimed to determine the seroprevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-2. Their results indicated that the seroprevalences of HSV-1 was 51.1% and the seroprevalence HSV-2 was 9.1% within their study sample between the ages of 15-44 (Howard et al., 2003). These results coincide with a review paper done by Wald in 2006 stating that the frequency of HSV-1 is increasing more than HSV-2. The statistics for America is higher when compared to Canada. However the prevalence of HSV-2 infection among Americans aged 14-49 has decreased from 21% to 16% from 1990 to 2010 (LeVay & Baldwin, 2012). This decrease may be due to great efforts spent on advertising medication that suppresses outbreaks.

When looking at global statistics, the World Health Organization (WHO) 67% of the population are infected with HSV-1 (WHO, 2015). The prevalence of HSV-2 is 11.3% globally, which is significantly lower compared to HSV-1 (Looker et al., 2015).

Risk Factors

Infection rate greatly depends on geographical location and socioeconomic status. Studies support that those with lower socioeconomic status generally report a higher HSV seroprevalence (Howard et al., 2003). The prevalence of HSV-1 and HSV-2 is highly variable according to the geographical locations of the population. For example, Eritrea has the highest reported prevalence of HSV-1 up to date, with 97% of the population over the age of 5 being seropositive (Smith & Robinson, 2002). Other risk factors of HSV-2 may include higher number of sex partners (Wald, 2004). This may be due to the fact that 90% of people infected with HSV-2 are unaware of this fact, and thus they are at a great chance of transmitting the disease (Leone & Corey, 2005).

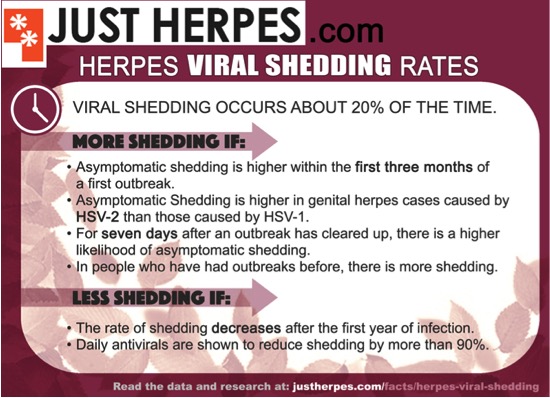

Although the chance of transmission is lower during the asymptomatic period, some studies suggest that the virus can be transmitted during periods of asymptomatic viral shedding. In a study done by Dr. Mertz and colleagues, 70% of patients appeared to get infected during the asymptomatic period (Mert, Benedetti, Ashley, Selke, & Corey, 1992). This study also showed that the risk of acquiring the infection was higher in women than men. Furthermore, exposure to HSV-1 infection was correlated with a reduction in the risk for acquisition of HSV-2 in women.

Pregnant females who are infected with herpes can put their infants at a great risk of exposure as the virus can be transmitted through the process of giving birth (LeVay & Baldwin, 2012). This is why it is often suggested for these group of females to undergo cesarean.

Symptoms

HSV-1

The primary symptoms of HSV-1 include blisters or open sores around the mouth. Due to these sores, individuals often experience pain and discomfort through symptomatic periods. HSV-1 herpes is highly contagious. Most HSV-1 infections are acquired through childhood. Majority of cases of HSV-1 show symptoms in or around the mouth (sometimes called Orolabial, oral-labial or oral-facial herpes), but some cases show signs around the genitalia, called genital herpes, or anal area. However, the majority of people who are infected with oral HSV-1 show no symptoms, as the infection itself is mostly asymptomatic. However, Symptoms of HSV-1 include painful blisters or open sores called ulcers in or around the mouth. Lesions on the lips are commonly referred to as “cold sores.” an Infected person will often experience a tingling, itching or burning sensation around his/her mouth, before the appearance of sores. After the initial infection, the blisters or ulcers can periodically recur. The frequency of recurrences varies from person to person. HSV-1 can also cause genital herpes in rare episodes. The symptoms can also be mild which include blisters on the genital or anal area or can be asymptomatic as well. In immunocompromised people, such as those with advanced HIV infection, HSV-1 can have more severe symptoms and more frequent recurrences. Rarely, HSV-1 infection can also lead to more severe complications such as encephalitis or keratitis (eye infection) (Herpes simplex virus, 2017).

HSV-2

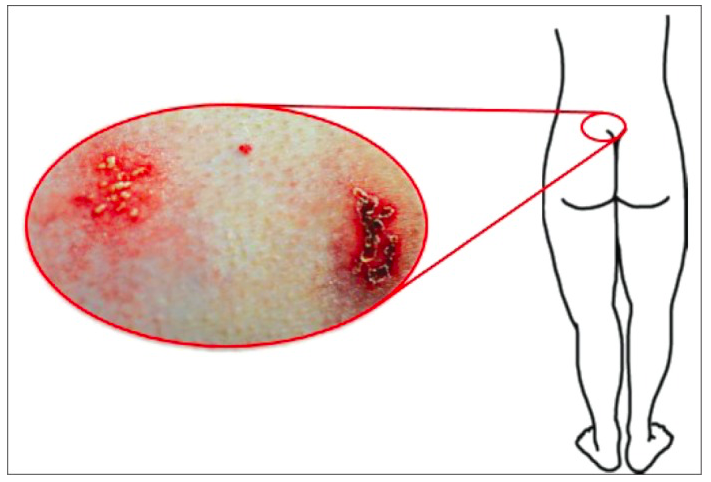

It's widespread around the world and is transmitted mainly through sexual intercourse. However, HSV-2 can also be sent through oral sex. The infections that follow HSV-2 are usually severe and incurable. HSV-2 is the leading cause of genital herpes, which can also be caused by herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) as mentioned earlier. Infection with HSV-2 is lifelong and incurable. Most people are unaware of their infections thinking its some rash on their private areas. An estimate of only 10-20% of people who are infected in HSV-2 reports a prior diagnosis of genital herpes. This also because most of the symptoms are also asymptomatic like in HSV-1 infections. When symptoms do occur, genital herpes is characterized by one or more genital or anal blisters or open sores called ulcers. In addition to genital ulcers, signs of recent infections of HSV-2 often include fever, body aches, and swollen lymph nodes. After an initial genital herpes infection with HSV-2, recurrent symptoms are common but usually less severe than the first outbreak. The frequency of outbreaks tends to decrease over time. People infected with HSV-2 may experience sensations of mild tingling or shoot pain in the legs, hips, and buttocks before the occurrence of genital ulcers (Herpes simplex virus, 2017).

Infections in Other Parts of The Body

One of the complications that can occur due to Herpes is that it can cause infection in the eye if an individual is exposed to a virus-shedding sore (Crooks, & Baur, 2014). This can lead to what is known as Ocular Herpes, or eye infection. To prevent getting an eye infection when one touches a virus-shedding sore, it is important to thoroughly wash hands with hot water and soap immediately after touching the lesions. There are also effective treatments for ocular herpes that must be started right away (Crooks, & Baur, 2014). HSV could also infect the skin and the mucosa layer of the skin through exposure (Whitley, Kimberlin, & Prober, 2007). The pulp or nail bed are the most common site of infection, and this type of infection is commonly referred to as the herpetic whitlow. The central nervous system (CNS) is also another site of infection for the HSV. Studies show that HSV-1 is the most common cause of sporadic severe encephalitis in America. Without any treatments, 70% of all those infected die, and the rest face severe consequences.

Transmission of HSV-1

Initial infection with HSV-1 is caused by contact with mucosal surfaces or abraded skin (Whitley & Roizman, 2001) in regions such as the lips, mouth, and skin above the waist (Nahmias, Keyserling & Lee, 1989). An individual can be affected with HSV-1 through close nonsexual contact with an affected individual such as kissing (even on the cheek), sharing utensils and sharing drinks, as the virus can remain viable for a brief period of time on skin, clothing and plastics (Fatahzadeh & Schwartz, 2007). An individual is most contagious when they are exhibiting cold sores or lesions, but is still contagious without showing symptoms.

HSV-1 invades surfaces through the interaction of cell surface receptors with viral glycoproteins (Heldwein & Krummenacher, 2008). Nectin-1 is a cell adhesion molecule and HVEM is the herpes virus entry mediator that is found on the surface of different cells (Shui & Kronenberg, 2013). Nectin-1 is found on oral epithelium cells and HVEM is expressed in approximately 40% of cells. One or both of these receptors bind with viral glycoproteins, with glycoprotein D being the principle glycoprotein. The virus then invades the epithelium through the basal layer (Thier et al., 2017).

.

Transmission of HSV-2

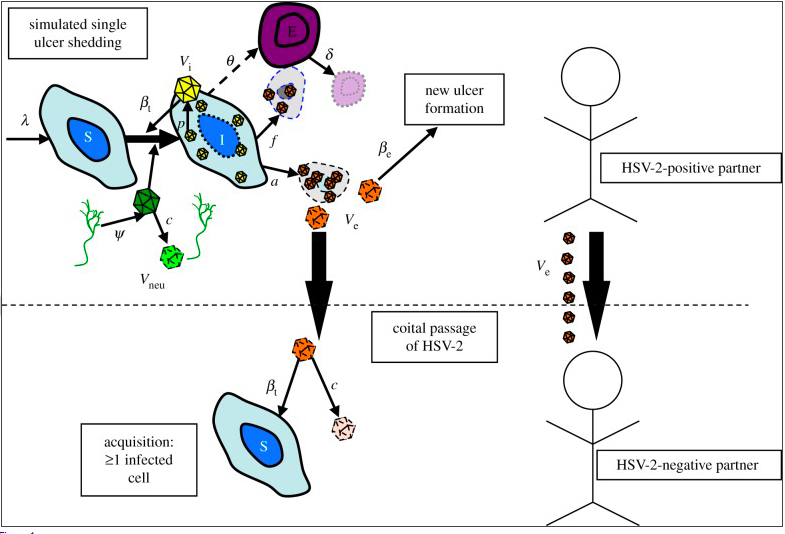

Transmission of HSV occurs when a person who is shedding the virus from a lesion or cyst in the genital tract or on other skin or mucosal surface, inoculates the virus onto a mucosal surface or small crack in the skin of a sexual partner. The duration of shedding is different per case, ranging from hours to weeks. Therefore, there is no way to be sure when individuals are not in a transmissive mode. Transmission to an uninfected partner happens during sexual intercourse during this genital shedding period (Figure —).

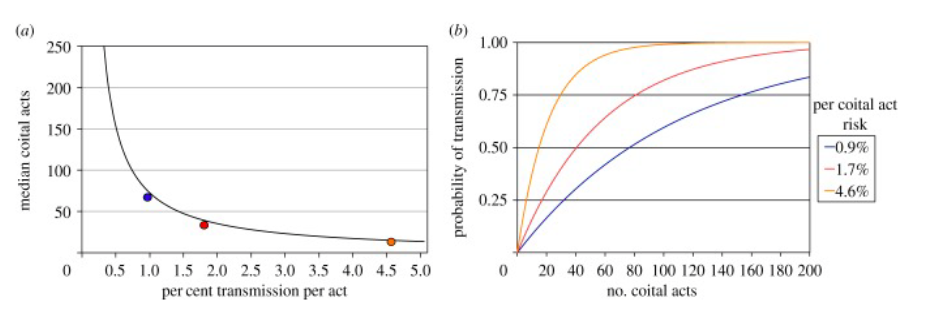

Figure 5: (a) illustrates the number of acts prior to transmission. The higher the probability of transmission, the lower number of sexual acts needed to transmit the virus. The orange, red and blue dots are the median number of acts prior to transmission needed that correlate with the lines in illustration (b). (b) shows the correlation between the number of sexual acts with the probability of transmission. (Schiffer, Mayer, Fond, Swan, & Wald, 2014)

Many episodes of HSV-2 are associated with visible lesions and cysts, but most transmission occurs during asymptomatic reactivation (no symptoms visible). This accounts for approximately 80% of the duration of shedding. Most clinical models suggest that episodes associated with sufficient viral load, have ulcers with a diameter smaller than 3mm and result in high transmission. Although, during episodes that do not have visible ulcers, the virus can still have a high viral load and transmit the virus efficiently before lesions are even visible. Studies have also shown that the number of times sexual intercourse takes place before transmission happens is relatively low. Under the assumption that all shedding during sex results in transmission regardless of viral load, a median of 3.5 sex acts would result in transmission (Figure 5) (Schiffer, Mayer, Fond, Swan, & Wald, 2014).

Figure 6: Visualizes the shedding of a lesion in an infected partner, with the transfer of the virus to the uninfected partner during sexual intercourse. It also illustrates infection, which happens when a virus enters and replicates within the neural cells of the uninfected individual (Schiffer, Mayer, Fond, Swan, & Wald, 2014)

After initial infection, the virus remains latent in neurons, this is a key feature of alpha herpesviruses. HSV 1 is predominately latent in trigeminal neurons, and HSV 2 in lumbosacral ganglia. The latency period is for reasons unknown. During this time, the virus can shed and again, transmit to partners via asymptomatic shedding of the virions. HSV 2 specifically, will eventually begin to spread cell to cell by innervating nerves such as sacral ganglia for this period of latency (Akhtar & Shukla, 2009).

Attachment and Recognition for HSV-1 & HSV-2

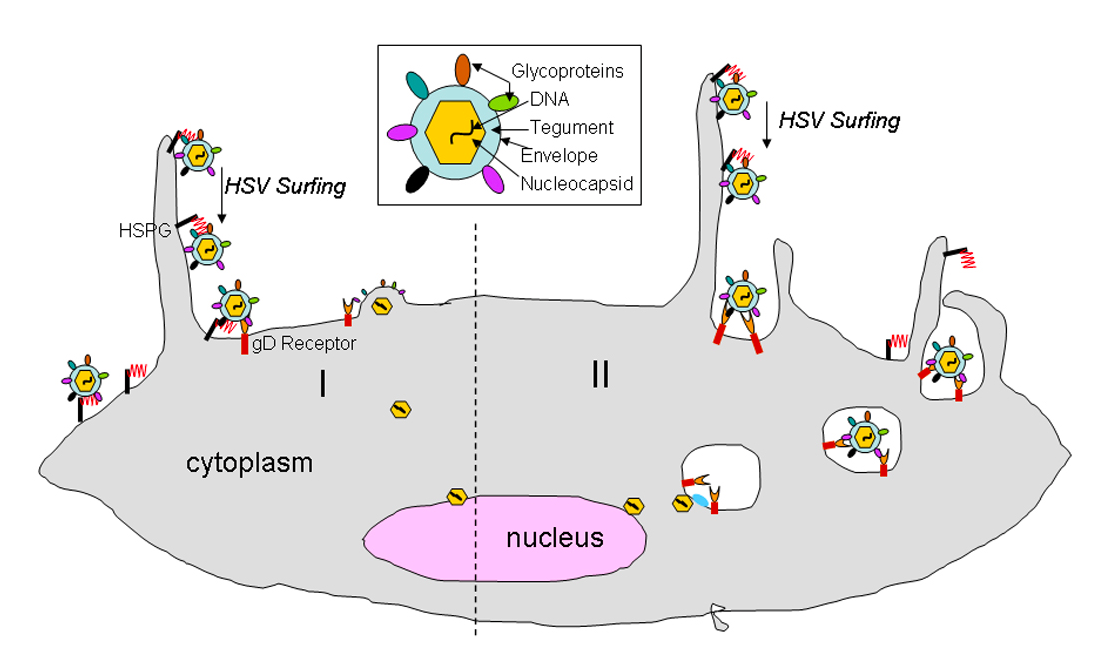

Both HSV 1 and 2 have a linear double-stranded DNA genome packaged into an icosahedral capsid. The capsid is also enclosed in a layer of proteins called the tegument. The tegument is covered by a lipid membrane bilayer consisting of membrane proteins and glycoproteins. This protected DNA genome is essential to the viral infectivity. The HSV virions can enter the host cells in two different ways. One is through a pH-independent fusion of the viral envelope with the plasma membrane, or via a pH-independent or dependent endocytic pathway using phagocytosis to uptake the viral particles. In both pathways, the HSV particles initially attache to host cells using an association between filopodia-like membrane protrusions, rich in actin, on the cells and heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG). Heparan sulphates (HS) are abundantly expressed on the surface of most cell types as HSPG. As HS possesses negative charges, it interacts well with positively charged glycoproteins. “HSV surfing” then occurs when the virus particles bound to the filopodia facilitates them closer to the cell body for entry via interactions between the glycoproteins on the HSV virus and other host cellular receptors such as gD, and gB receptors. The “surfing” of the virus closer to the host cell is accomplished via myosin- dependent F-actin retrograde flow (Figure 8)

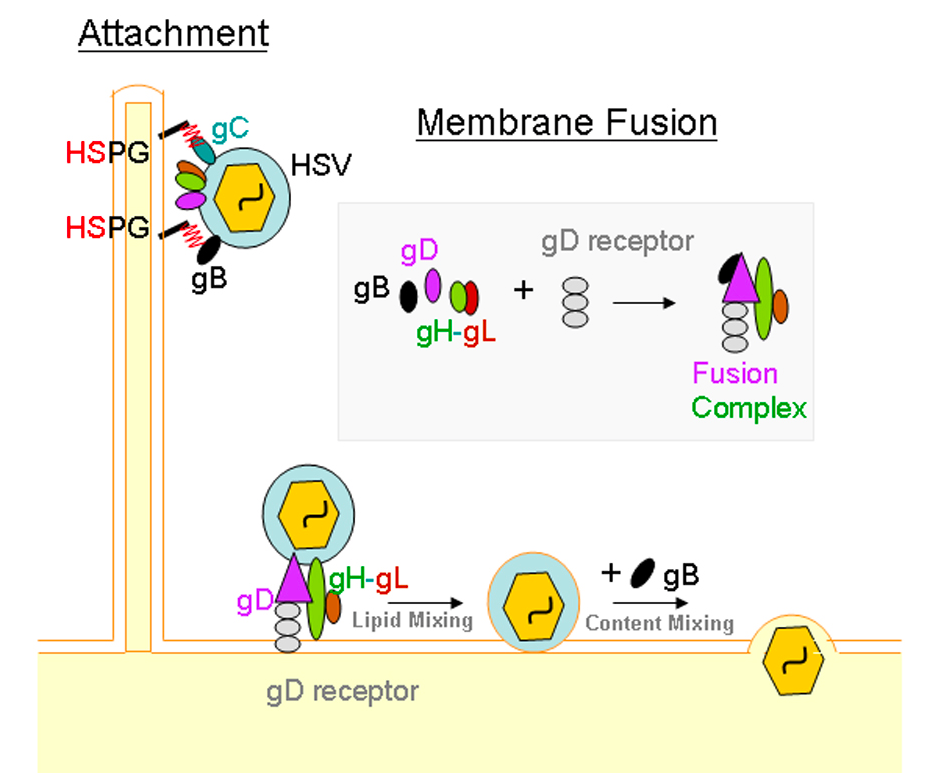

The current model for membrane fusion between HSV and the host cell suggests that binding to one of the gD receptors using Nectin-1 (both HSV-1 and HSV-2) and Nectin-2 (HSV-2) induces a conformational change in gD that initiates the fusion between the virus and the host cell. The conformational change activates a multi-glycoprotein complex involving gB, gD, gH, and gL receptors. Once the viral envelope is fused with the cellular membrane, viral and cellular membranes are merged and lipid mixing occurs. This results in the release of the viral nucleocapsid and tegument proteins into the host cell’s cytoplasm. The gB receptor is primarily responsible for this (Figure 8) With endocytosis, the enveloped particles through phagocytosis fuse with a vesicular membrane. Using similar interactions between gB, gD, gH, and gL, and host cell receptors, except all in an endosome, facilitate the fusion with host cell membrane. Whether or not the virus using endocytosis or fusion at the plasma membrane is dependent upon individual cell types that they encounter. In Vero and Hep2 infected cells, there is no preference. However, in CHO, HeLa, RPE, human epidermal keratinocytes and KCjE cells, there is a preference for endocytosis. (Akhtar & Shukla, 2009)

Post Entry Into Host Cell for HSV-1 & HSV-2

Once the HSV has entered the cytoplasm of the host cell, HSV nucleocapsids dissociate with tegument proteins and bind to a microtubule dependent minus end-directed motor dyenin. This allows the virus to be transported towards the nuclear membrane using a dynein-propelled mechanism. Once it arrives at the nuclear membrane, the virus is uncoated and then the viral DNA can be released into the nucleus of the host cell. Once internalized inside the nucleus, transcription and replication of the virus can take place in the nucleus in order to spread and further infect (Akhtar & Shukla, 2009).

Neural Cells Affected by HSV-1

After the virus invades the epithelium and replicates, it travels to the trigeminal ganglia and surrounding sensory neurons in retrograde via nerve termini where the virus will be latent (Nicoll, Proenca, & Efstathiou, 2012). HSV-1 can then reactivate due to physical and emotional stress, tissue damage, fever and ultraviolet light (Whitley & Roizman, 2001). During the latent phase, gene expression is suppressed, but increased during the reactivation phase through the expression of lytic cycle genes (Margolis, Imai, Yang, Vallas, & Krause, 2007). As a result, the virus then travels anterograde back to the epithelium producing lesions and sores (Liu, Khanna, Carriere, & Hendricks, 2001).

Neural Cells Affected by HSV-2

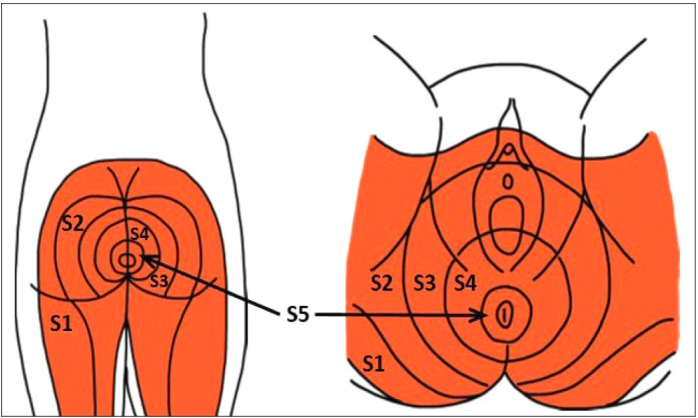

HSV-1 and HSV-2 are very similar except for differences in site-specific activation of symptoms. Once the virus has infected the cells, it enters a dormant state and can establish a lifelong latent infection in sensory neurons of the central nervous system that innervate the site of primary, and productive infection. The latency of the virus is important because it forms a reservoir of the virus to produce recurrent infections, disease, and transmission to other individuals. HSV-2 is associated with latent infection in the lumbosacral dorsal root ganglia (DRG), giving rise to the symptoms below the waist and predominantly in the genital area (Figure 10 and 11) (Kramer, Cook, Roth, Khu, Holman, Knipe, & Coen, 2003).

The specific effects that HSV-2 has on these neurons is still under extensive research. However, researchers do know that latent HSV-2 infection changes the gene expression in these neurons and attaches to neurons that are KH10 positive. HSV-2 acts by inducing neuronal injury or by inducing a persistent immune response to the latent infection that induces the expression of cytokines which are also known to alter gene expression. Specifically, it can cause an increase of Stat1 in neurons. In addition, studies have shown that altered gene expression causes changes in Gprc1g, Gabbr1, Kcnab2, and Kcnc1 genes, affecting the neuronal excitability in an interconnected manner. The changing of the neuronal physiology alters sensations in this area and the latently infected ganglia exhibit alterations in ion channel functioning, leading to the commonly observed symptoms in the genitals (Kramer, Cook, Roth, Khu, Holman, Knipe, & Coen, 2003).

Crossover between HSV-1 and HSV-2

The difference between the two virus types is in their latency stage. HSV-1 remains dormant in the nerve cells in the neck region, hence the outbursts on the face and mouth. HSV-2 remains dormant in the nerve cells located at the base of the spine, hence the outbursts in the genitals (Pierce, n.d.). Although they differ in where they remain dormant, it is possible and quite common for the viruses to crossover to different regions from the upper body to the lower body, and vice versa. Therefore, HSV-1 can cause genital herpes and HSV-2 can cause oral herpes. HSV-1 can cause genital herpes due to the fact that the lesions of the mouth also undergo the process of “shedding” and during oral sex, come into contact with mucosal membranes, gaining access to entering the body. This can also happen in a reverse fashion. If an individual has HSV-2 and oral sex is performed, the unaffected partner can contract oral herpes by being exposed to HSV-2 due to the same shedding process of the lesions. Therefore, allowing the virus to gain access to mucosal membranes in the mouth area (STDcheck, 2015). In addition, it is important to note that HSV-1 and HSV-2 do invade different neurons - HSV-1 being trigeminal ganglia and HSV-2 being the lumbosacral dorsal root ganglia. However, HSV-1 is characterized by two different patterns of gene expression. When there is an abundant expression of lytic cycle genes, the HSV-1 virus is infective in some neurons, whereas in other neurons, latency is established. This is all controlled by which neurons express either MAb KH10 (productive infection), or MAb A5 (latent infection). Both of these factors are expressed predominantly on trigeminal ganglia, but also can be found on lumbosacral DSG. In contrast, HSV-2 infects KH10-positive neurons which are primarily found in the lumbosacral DSG, but also in the trigeminal ganglia. Nonetheless, these viruses can take advantage of two different biological niches. Therefore, this phenomenon explains why it is possible to have crossovers between the two viruses, as well as why they are able to infect opposite areas of the body (Margolis, Lmai, Yang, Vallas, Krause, 2007).

Treatment/Management of HSV

As of right now, there is no effective treatment available for the Herpes Simplex Virus (Crooks, & Baur, 2014). There is optimism for the future that there will be the development of a Herpes vaccine, however currently, there are only ways to prevent the virus, reduce the discomfort that it causes the person, and speed the healing process during an outbreak of the virus (Crooks, & Baur, 2014).

Treatment for Oral and Genital Herpes

Oral Acyclovir, when taken several times a day, has shown to be an effective treatment for Genital Herpes (Crooks, & Baur, 2014). Valacyclovir (Valtrex) and Famciclovir (Famvir) are two other antiviral agents that also manage Genital Herpes. Genital Herpes can recur as well. There are two antiviral treatment strategies that are used to manage it, Suppressive Therapy and Episodic Treatment. The Suppressive Therapy medication is to be taken daily to prevent recurrent Genital Herpes. The medication often prevents the reactivation of the Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) and the development of herpes lesions. This medication also reduces viral shedding that is asymptomatic and between the outbreaks that may occur. It also reduces the risk of the transmission of HSV infections sexually (Crooks, & Baur, 2014). Suppressive Therapy reduces the recurrence rate of Genital Herpes by about 70%-80% in those who have frequent outbreaks (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Evidence from documentation shows that treatment is effective and safe among patients who have been receiving daily therapy of Acyclovir for about 6 years and with Valacyclovir or Famciclovir for 1 year. They have reported that their quality of life has improved in many patients with frequent recurrences who have been receiving Suppressive Therapy rather than Episodic Treatment. For the treatment with Valacyclovir, they say 500mg daily decreases the rate of Genital Herpes transmission in heterosexual couples where the source partner has a history of Genital Herpes infection. Suppressive Therapy is also likely to reduce transmission when a person who has multiple partners, uses it and also by those who are seropositive but without having a history of genital herpes (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015). Episodic Treatment is used when herpes outbreaks occur, and they involve antiviral agents (Crook, & Baur, 2014). This treatment reduces the severity and duration of lesion pain and the time needs for healing is also reduced.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Recommended Treatments for Suppressive Therapy for Genital Herpes

- Acyclovir 400 mg orally twice a day

- Valacyclovir 500 mg orally once a day*

- Valacyclovir 1 g orally once a day

- Famiciclovir 250 mg orally twice a day

*Valacyclovir 500 mg once a day may be less effective than other Valacyclovir or Acyclovir dosing treatments in people who have recurrences often (Ex. Greater than or equal to 10 episodes per year) (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015).

Episodic treatment however does not reduce the risk for transmitting HSV to as sexual partner like Suppressive Therapy does (Crooks, & Baur, 2014). Episodic Treatment is effective for recurrent genital herpes when the therapy is initiated within a day of lesion onset or during the prodrome that follows the outbreaks. When the symptoms begin, it is important to provide the patient with a supply of drug or a prescription for the medication with the instructions so that they can start their treatment right away (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015).

Recommended Treatments for Episodic Treatment for Genital Herpes

Listed below are various recommended treatments (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2015):

- Acyclovir 400 mg orally three times a day for 5 days

- Acyclovir 800 mg orally twice a day for 5 days

- Acyclovir 800 mg orally three times a day for 2 days

- Valacyclovir 500 mg orally twice a day for 3 days

- Valacyclovir 1 g orally once a day for 5 days

- Famciclovir 125 mg orally twice daily for 5 days

- Famciclovir 1 gram orally twice daily for 1 day

- Famciclovir 500 mg once, followed by 250 mg twice daily for 2 days

Acyclovir: Mechanism of Action

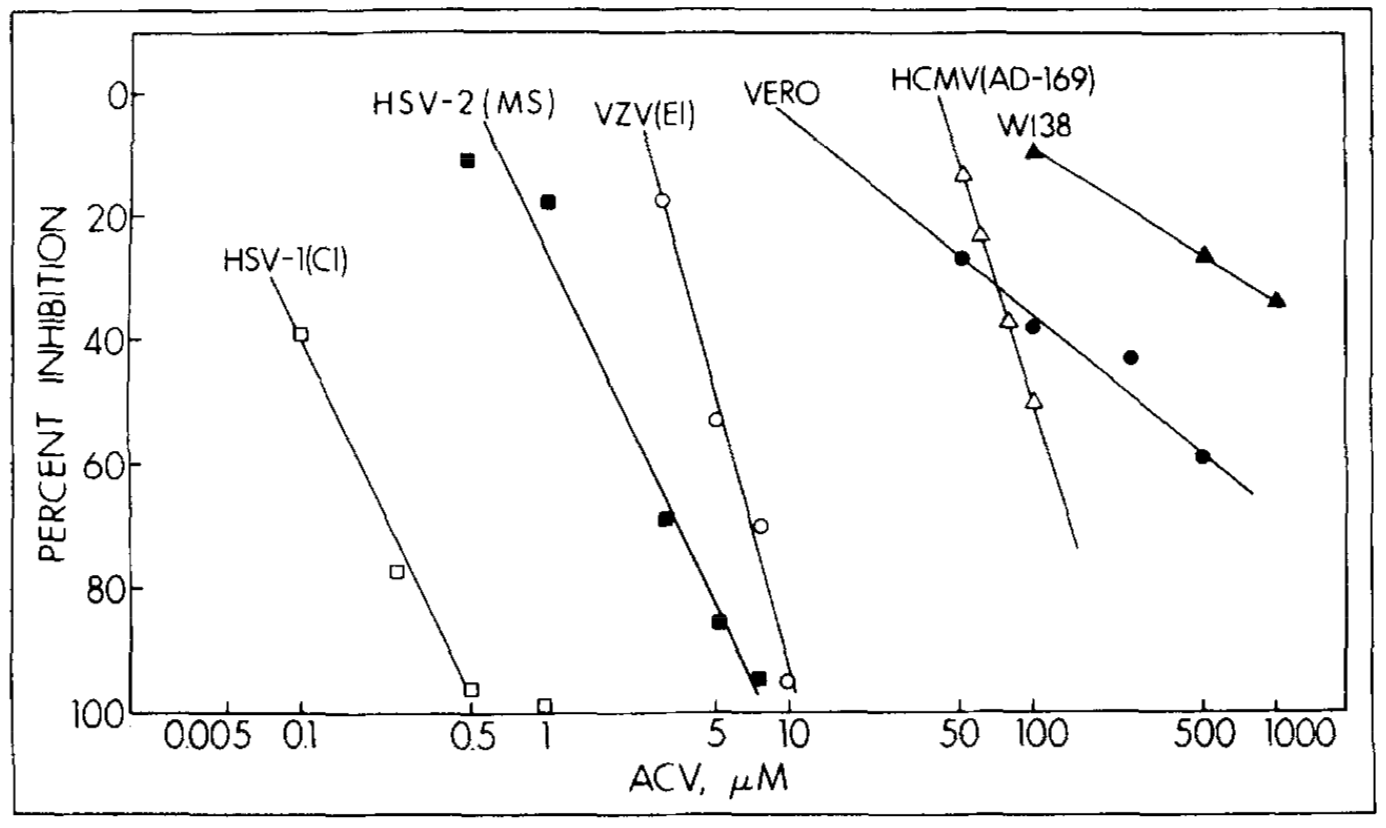

Acyclovir acts to inhibit the viral replication of HSV-1 and HSV-2 (Jane, 2011). It interferes with the synthesis of viral DNA. This reduces the viral shedding and reduces the time for healing of the lesions (Jane, 2011). Acyclovir, is an acyclic purine nucleoside analog that is a very potent inhibitor of Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV) (Elion, 1982). It has a significantly low toxicity for the host cells. The virus code for a viral thymidine kinase that can phosphorylate Acyclovir to a monophosphate form that uninfected cells are not able to do. This causes selectivity by Acyclovir. The monophosphate Acyclovir (acyclo-GMP) is converted to Acyclovir triphosphate (acyclo-GTP) by the virus cells. Acyclo-GTP stays in the HSV-infected cells for hours even after Acyclovir is removed. The amount of acyclo-GTP present in the HSV-infected cells is much greater than in non-infected cells. It is the Acyclo-GTP form of Acyclovir that acts as a potent inhibitor of the viral DNA polymerase in Oral Herpes (HSV-1), and Genital Herpes (HSV-2). Both HSV-1 and HSV-2’s DNA polymerase bind very strongly to the acyclo-GMP-terminated template, and gets inactivated (Elion, 1982).

Effects of Acyclovir

An experiment done by Elion and team, looked at the activity of acyclo-GTP in viral DNA (Elion, 1982). The replication of Herpes Viruses depend on a virus-specific DNA polymerase that is different than that of cellular DNA polymerase. In this experiment, Elion looked at how a strain of virus that has its own DNA polymerase and its own sensitivity is affected by acyclo-GTP. The activity of DNA polymerase was measured by its ability to include dTTP into an activated DNA template with the presence of dCTP, dATP, and dGTP. It is important to note that Acyclovir had not effect on the rate of reaction, however acyclo-GTP was acting in an inhibitory manner. The reaction rate of the inhibited reaction for the initial 15 minutes was linear. However, at higher concentrations, about 20 microM, the reaction rate of the viral DNA polymerase was decreased and almost ceased. When inhibition constants for each DNA polymerase were calculated for viral and cellular DNA polymerase, it became evident that cellular DNA polymerases were much less sensitive to acyclo-GTP than viral DNA polymerase, proving the selectivity aspect of Acyclovir. These results aided in showing that Acyclovir is selective (Elion, 1982).

The mechanism of action is very similar for Valacyclovir and Famciclovir as well, they both act to inhibit the replication of the viral DNA in the host’s body.

Other treatments for oral herpes include:

- A topical anesthetic such a Lidocaine (Dilocaine, Nervocaine, Xylocaine, Zilactin-L) to relieve pain

- Oral or IV medication for those with a weakened immune system, infants who are younger than 6 weeks, or those with severe disease

Serious cases may require hospitalization such as:

- Severe local infection

- Infection which has spread to other parts of the body

- Individuals who have been dehydrated and need IV hydration (DerSarkissian, 2016)

Management of Genital Herpes

To manage Genital Herpes, there are a number of ways a person can go about doing that (Crooks, & Baur, 2014). This may vary from person to person and it is encouraged that they try different ways to manage the virus.

Keep blisters dry and clean

This will reduce the chances of secondary infections, shorten the period of viral shedding, and speed up lesion healing. It is important to wash the area of concern with warm water and soap 2-3 times a day. After bathing, it is important to dry the area thoroughly by gently patting it using a soft cotton towel or blow drying the area with a hair dryer that is on Cool. It is important to keep the area dry as mentioned before and so sprinkling the dried area with cornstarch or baby powder can also be helpful. It is recommended to wear loose cotton clothing that does not trap moisture and keeps the area dry.

Take 2 aspirin every 3 to 4 hours to help reduce the pain and itching

Local anaesthetic such as lidocaine jelly, can help to reduce soreness. Ice packs can be applied directly to the area of lesions as it provides temporary relief but it is important to note not to wet the lesions when using an ice pack as ice melts. One can powder the area to reduce and alleviate the itching.

Drink lots of fluids

One of the symptoms some can have is intense burning sensation when urinating if the urine comes in contact with the lesions. This is discomforting and it can be reduced by pouring water over the genitals while urinating or to urinate in a bathtub filled with water. Drink a lot of fluids to help dilute the acid in the urine, but avoid liquids that may cause the urine to become more acidic, such as cranberry juice.

Reduce stress

It had also been implicated that stress can trigger the recurrence of herpes, and so it is a good idea to reduce negative influence that may be causing stress. To do this, one may try different relaxation techniques, Yoga, or meditations, and using counselling to cope with the daily pressures.

Recognize common occurrences

If one is prone to getting recurrent herpes, it may be helpful to record the events that occur right after the outbreak to see if they are able to recognize any common events that occur such as fatigue, stress, or even excessive sunlight. This way, they can avoid such events in the future and reduce the number of relapses of herpes (Crooks, & Baur, 2014).

Management for Oral Herpes

For the management of oral herpes, one can use Acetaminophen (such as Feverall, Panadol, and Tylenol) or Ibuprofen (such as Ibuprin, Advil, and Motrin) for fever and muscle aches as they are some of the symptoms in people who are diagnosed with Oral Herpes. It is also important for people with Oral Herpes to drink plenty of fluids, use the pain medications that as prescribed by the doctor, and watch for signs and symptoms of dehydration (DerSarkissian, 2016).

Prevention

Oral Herpes

There are some simple preventative measures one can take to avoid getting oral herpes in the first place. These include (American Academy of Dermatology, 2018):

- Avoiding direct physical contact with others

- Not sharing items that can spread the virus around such as towels, silverware, clothing, makeup, cups, and lip-balm

- Not engaging in oral sex, kissing or any other type of sexual activity during an outbreak

- Washing your hands thoroughly

Genital Herpes

- Avoid having sex with infected partners

- Use a latex condom to lower the risk of spreading the virus if you cannot stay away from infected partners (however, be aware that it is possible to spread the virus it if lies nearby the skin that the condom does not cover)

- If you are pregnant, let your doctor know if you or your partner has genital herpes to take prepare precautions to not transfer the virus to your baby (American Academy of Dermatology, 2018).

Getting Tested

Many clinics around the world, especially in North America, offer a type-specific blood test for both HSV-1 and HSV-2. These blood tests look for antibodies to HSV-1 and HSV-2 in the patient's blood. These tests usually test for genital infections. For instance, HSV-2 can be detected as early as three weeks after possible exposure. However, it's recommended to wait between 3-6 weeks to get tested for more accurate results. After three months post-exposure to the virus, getting tested again is advised to eliminate the possibility of recurrent infection. Testing for HSV-1 in the blood is done using the Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) test. This HSV-1 specific blood test looks for antibodies to the HSV-1 virus in the bloodstream. This test is highly sensitive and will only detect the presence of HSV-1 antibodies. Since HSV-2 causes 20% of oral herpes cases, we recommend ordering both the HSV-1 test and HSV-2 test. After taking both tests, results will read as either positive (HSV-1 or HSV-2 is found in blood) or negative (no HSV-1 or HSV-2 virus is found in blood) (Genital Herpes Overview, 2018).

Where is Treatment Available?

Treatment is available at your local pharmacy and even online. In Hamilton specifically there are health units that provide services related to the testing of STIs, information of STIs, etc..

Conclusion

HSV-1 and HSV-2 most commonly infect humans. HSV-1 predominantly affects regions above the waist as the virus binds to A5 and KH10 receptors on the trigeminal ganglia located in the brain. HSV-2 predominantly affects regions below the waist as the virus binds to the KH10 receptors that are in abundance in the lumbosacral root ganglia located the base of the spine. Crossover between the two types occurs as well due to both ganglia having the KH10 receptor. Although HSV is not curable, there are numerous treatment options, with episodic and suppressive therapies being two in particular.

References

- Akhtar, J., & Shukla, D. (2009). Viral entry mechanisms: cellular and viral mediators of herpes simplex virus entry. The FEBS journal, 276(24), 7228-7236.

- American Academy of Dermatology. (2018). Herpes Simplex: Tips for Managing. American Academy of Dermatology Association. Retrieved from https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/contagious-skin-diseases/herpes-simplex#tips

- Baugher, Jessie. (2018). Mouth Herpes Symptoms and Treatment. Retrieved from https://www.shelbydentalcare.com/mouth-herpes-symptoms-and-treatment

- Crooks, R., & Baur, K. (2014). Our Sexuality. Belmont, CA: Jon-David Hague.

- DerSarkissian, C. (2016). Oral Herpes. WebMD. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/oral-herpes#3-6

- Danziger, P (2016). Could A Zika Virus Break the Vaccine Stalemate? Slate. Retrieved from http://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/medical_examiner/2016/09/the_zika_vaccine_could_convince_anti_vaxxers_of_vaccines_necessity.html

- Dokter Online (2018). Famvir. Doktoronline.com. Retrieved from https://www.dokteronline.com/en/famvir-famciclovir

- Elion, G. B. (1982). Mechanism of action and selectivity of acyclovir. The American journal of medicine, 73(1), 7-13.

- Fatahzadeh, M., & Schwartz, R.A. (2007). Human herpes simplex virus infections: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, symptomatology, diagnosis, and management. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 57(5), 737-763.

- Genital Herpes Overview .(2018). STD Check. Retrieved from https://www.stdcheck.com/herpes-2.php

- Heldwein, E.E., & Krummenacher, C. (2008). Entry of herpesviruses into mammalian cells. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences, 65(11), 1653-1668.

- Herpes simplex virus. (2017). World Health Organization Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs400/en/# hsv1

- Herpes Simplex. (2018). American Academy of Dermatology Association. Retrieved from https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/contagious-skin-diseases/herpes-simplex#symptoms

- Howard, M., Sellors, J. W., Jang, D., Robinson, N. J., Fearon, M., Kaczorowski, J., & Chernesky, M. (2003). Regional distribution of antibodies to herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) and HSV-2 in men and women in Ontario, Canada. Journal of clinical microbiology, 41(1), 84-89.

- Jane, D. (2011). Acyclovir-Drug Study. Nursingcrib. Retrieved from http://nursingcrib.com/drug-study/acyclovir-drug-study/

- John Hopkins University. (2018). Oral Herpes. John Hopkins Medicine. Retrieved from https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/healthlibrary/conditions/adult/infectious_diseases/Oral_Herpes_22,OralHerpes

- Just Herpes. (2015). Herpes Viral Shedding: The Research and the Rates. Just Herpes. Retrieved from http://justherpes.com/facts/herpes-viral-shedding/

- Karki, G. (2018). Herpes simplex virus(HSV): Structure and genome, mode of transmission, pathogenesis, infection, laboratory diagnosis and treatment -. Retrieved from http://www.onlinebiologynotes.com/herpes-simplex-virushsv-structure-genome-mode-transmission-pathogenesis-infection-laboratory-diagnosis-treatment/

- Kramer, M. F., Cook, W. J., Roth, F. P., Zhu, J., Holman, H., Knipe, D. M., & Coen, D. M. (2003). Latent herpes simplex virus infection of sensory neurons alters neuronal gene expression. Journal of virology, 77(17), 9533-9541.

- Leone, P. & Corey, L. (2005). Genital herpes: prevalence, transmission, and prevention. Retrieved from: https://www.medscape.org/viewarticle/502718_3

- LeVay, S., & Baldwin, J. I. (2009). Human sexuality. Sunderland, Mass: Sinauer Associates.

- Liu, T., Khanna, K.M., Carriere, B.N., & Hendricks, R.L. (2001). Gamma Interferon Can Prevent Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Reactivation from Latency in Sensory Neurons. Journal of Virology, 75(22), 11178-11184.

- Looker, K. J., Magaret, A. S., Turner, K. M., Vickerman, P., Gottlieb, S. L., & Newman, L. M. (2015). Global estimates of prevalent and incident herpes simplex virus type 2 infections in 2012. PloS one, 10(1), e114989.

- Margolis, T. P., Imai, Y., Yang, L., Vallas, V., & Krause, P. R. (2007). Herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) establishes latent infection in a different population of ganglionic neurons than HSV-1: role of latency-associated transcripts. Journal of virology, 81(4), 1872-1878.

- MedlinePlus. (2018). Herpes-oral. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/000606.htm

- Mertz, G. J., Benedetti, J., Ashley, R., Selke, S. A., & Corey, L. (1992). Risk factors for the sexual transmission of genital herpes. Annals of Internal Medicine, 116(3), 197-202.

- Nahmias, A.J., Keyserling, H., & Lee, F.K. (1989). Herpes Simplex Viruses 1 and 2. Viral Infections of Humans. New York: Plenum Publishing Corporation.

- Nicoll, M.P., Proenca, J.T., & Efstathiou, S. (2012). The molecular basis of herpes simplex virus latency. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 36(3), 684-705.

- Payne, W.A., Hahn, D.B., & Lucas, E.B. (2013). Understanding Your Health. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Pettersson, N. (2013). Valacyclovir HCl. hsvtype1.com. Retrieved from http://hsvtype1.com/valacyclovir-hcl.html

- Pierce, J.M. What is the difference between HSV1 & HSV2? Oral and Genital Herpes. The STD Project. Retrieved from https://www.thestdproject.com/what-is-the-difference-between-hsv1-hsv2-oral-and-genital-herpes/

- Public Health. (2018). Clinics & Services. Hamilton. Retrieved from https://www.hamilton.ca/public-health/clinics-services

- Schiffer, J. T., Mayer, B. T., Fong, Y., Swan, D. A., & Wald, A. (2014). Herpes simplex virus-2 transmission probability estimates based on quantity of viral shedding. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 11(95), 20140160.

- Shui, J.W., & Kronenberg, M. (2013). HVEN: An unusual TNF receptor family member important for mucosal innate immune responses to microbes. Gut Microbes, 4(2), 146-151.

- Smith, J. S., & Robinson, N. J. (2002). Age-specific prevalence of infection with herpes simplex virus types 2 and 1: a global review. The Journal of infectious diseases, 186(Supplement_1), S3-S28.

- STDcheck. (2015). Getting Genital Herpes from Oral Herpes & Vice Versa. Exposed. Retrieved from https://www.stdcheck.com/blog/getting-genital-herpes-from-oral-herpes-vice-versa/

- Taylor, S. (2018). Herpes Simplex. healthline. Retrieved from https://www.healthline.com/health/herpes-simplex

- Thier, K., Petermann, P., Rahn, E., Rothamel, D., Bloch, W., & Knebel-Morsdorf, D. (2017). Mechanical Barriers Restrict Invasion of Herpes Simplex Virus 1 into Human Oral Mucosa. Journal of Virology, 91(22), e01295-17.

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. (2015). Genital HSV Infections. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/herpes.htm

- Vassantachart, J. M., & Menter, A. (2016). Recurrent lumbosacral herpes simplex virus infection. Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, 29 (1), 48-49.

- Wald, A. (2004). Herpes simplex virus type 2 transmission: risk factors and virus shedding. Herpes: the journal of the IHMF, 11, 130A-137A.

- Wald, A. (2006). Genital HSV‐1 infections. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82(3), 189–190. http://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2006.019935

- Whitley, R., Kimberlin, D. W., & Prober, C. G. (2007). Pathogenesis and disease.

- Whitley, R. J., & Roizman, B. (2001). Herpes simplex virus infections. The Lancet, 357(9267), 1513-1518.

- WHO (2015). Globally, an estimated two-thirds of the population under 50 are infected with herpes simplex virus type 1. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/herpes/en/