Table of Contents

Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome

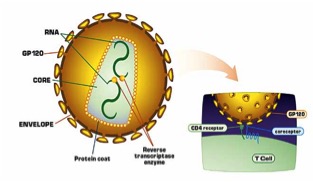

Human Immunodeficiency Virus, or HIV, is a retrovirus that causes AIDS, or acquired immune deficiency syndrome. It does this by infecting immune cells in the body, specifically CD4+ T cells, making the infected host vulnerable to infection. Without proper treatment of HIV, AIDS can take up to 8 years to develop, which can make diagnosis difficult (Sharp, 2011). An image of an infected CD4+ T cell can be seen in Figure 1 (right).

Introduction

Origins

HIV has two known strains, HIV-1 and HIV-2. The strain that is most commonly associated with AIDS pathogenicity is HIV-1. These strains originated from the Simmian Immunodeficiency Virus, or SIV, which initially infected several primates in Africa. Through cross-species transmission, several genetic modifications were made to SIV, allowing it to infect humans, leading to the classification of HIV (Sharp, 2011).

Once in the human population, the incredible pathogenicity of the virus allowed it to turn into a pandemic eventually killing millions of people around the world. It is thought that Hunters in West Africa were exposed to infected blood in primates, and initially contracted the virus. After this, through international travel and changes in patterns of sexual behaviour, the virus was able to transmit into several areas in the world (Sharp, 2011).

History of HIV/AIDS

<style justify>

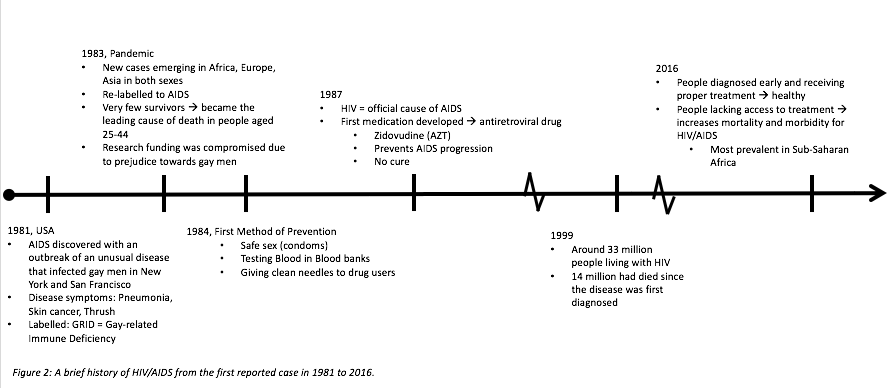

In 1981, AIDS first broke out in the US amongst gay men in New York and San Francisco. They were initially classified as having a mysterious pneumonia-like disease that presented with a rare from of skin cancer, thrush, and other characteristic symptoms. Since this was highly prevalent in gay men, the name for this disease was called GRID, or Gay-related Immune Deficiency (Holland, 2013).

In a matter of 2 years, AIDS became a pandemic. This was largely due to the fact that research funding was compromised due to the prejudice surrounding gay men at the time. This halt in research gave the virus time to spread across the world, such as Africa, Europe, and Asia. More importantly, the disease was found to be prevalent in both sexes, which contradicted the initial theory that gay interactions lead to the disease, and so it was re-labelled to AIDS. Unfortunately, AIDS became the leading cause of death in people aged 25-44, however, this statistic accelerated research surrounding the disease (Holland, 2013)

Since finding a cure to AIDS was incredibly difficult, the goal was shifted to AIDS prevention. In 1984, the first method of prevention was established based on the finding that AIDS was primarily transmitted through sexual intercourse associated with mucosal membrane abrasions, and blood transfusions. Thus, prevention methods included the promotion of safe sex (especially through the use of condoms), testing blood in blood banks, and giving clean needles to drug users (“A Timeline of HIV/AIDS”, n.d).

By the late 1980s, HIV was officially labelled as a retrovirus that causes AIDS. As research surrounding the properties of retrovirus continued, the first anti-retroviral drugs were created and administered. One of these drugs was called zidovudine, or AZT. This prevented AIDS progression, rather than providing a cure (Holland, 2013).

However, despite advances in AIDS therapy, the majority of people suffering from AIDS did not have proper health care or access to treatment. The region with the highest prevalence of AIDS was in Sub-Saharan Africa. By 1999, around 33 million people, including women, children and men, were living with HIV. Since the first reported case of AIDS in the 1980s, around 14 million people had died (“Global HIV/AIDS Overview”, 2016).

Today, testing methods for AIDS are quick, and easily determined which allows for early diagnosis. These people must continue to take anti-retroviral therapy for the rest of their lives to prevent AIDS progression, but they can live healthy lives. However, there are still a large proportion of people, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, who do not have access to either prevention methods (like safe sex), or anti-retroviral treatment (Holland, 2013).

Currently, 36.7 million people are living with AIDS, 1.8 million of cases are in children. Since the start of the epidemic, 35 million people have died. However, the number of people receiving treatment drastically increases every year, with 17 million people receiving anti-retroviral treatment this year, which is 10 million higher than the statistic 2 years ago. Of the total pregnant women suffering from HIV, 77% of them are being treated, and there has a 50% decline in the rate of incidence in newborns, which again, is a huge advancement (“Global HIV/AIDS Overview”, 2016). A summarized version of the timeline can be seen in Figure 2 (below).

</style>

Epidemiology

<style justify>

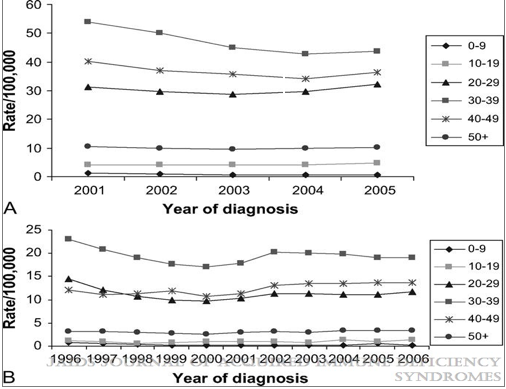

National surveillance systems in Canada and the United states have been used to observe the trends in AIDS and HIV. In 2005 AIDS diagnosis rates in the United states were substantially higher in blacks, followed by hispanics and then caucasians. In Canada, the AID diagnosis were higher for aboriginal peoples, then blacks, and substantially lower for caucasians. In both countries the trend was seen that HIV diagnosis increased for men who were having sex with men, and in general men were diagnosed at substantially higher rates than women. The age group with the highest rate of diagnosis was 30-39. In Canada, the rates peaked in 1984-1985, which is associated largely with the male homosexual population increase. After 1985, a steady decrease is seen until the early 1990s which was followed by another peak during 1996 and 1997. This peak can be linked back to the high infection rates among the injection drug users population. Incident infections may have increased somewhat since the late 1990s, but there is a great deal of uncertainty associated with recent incidence estimates and if present, this increase is much less than that seen in the early 1980s. At any rate, it can be stated with more certainty that diagnosis rates have not decreased in recent years. There is a need for prevention efforts in order to reduce the diagnosis rates, especially in ethnic minorities, as well as men who have sex with men. (Hall, 2009)

Figure 3: Rates of HIV diagnosis by age, 33 US states (A) and Canada. Retrieved from:http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/qai.0b013e3181a2639e

</style>

Mechanism of Action

Viral Structure

<style justify>

HIV is a type of RNA virus that is enclosed by a phospholipid envelope. The surface of the virus contains protrusions consisting of 3-4 GP41 glycoproteins, which are then capped by GP120 glycoproteins. The GP120 proteins are what will bind to the receptors of immune cells to allow viral infection of HIV. Within the envelope of the virus, there is a protein nucleocapsid, which surrounds two single stranded RNA molecules as well as enzymes important for viral functioning. These enzymes include reverse transcriptase, protease and integrase. Reverse transcriptase is used to create a DNA molecule from an RNA template. Protease is involved in the cleavage of proteins, which allows for activation of the HIV virus. Finally, integrase allows viral DNA to be inserted into the host cell’s chromosome (Berger et al., 2016).

</style>

Figure 4: Structure of viral HIV. Retrieved from: https://learner.org/courses/biology/units/hiv/index.html

HIV Life Cycle

<style justify>

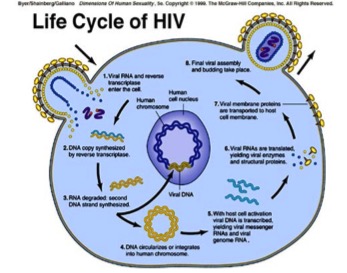

The HIV virus first gains entry into the host cell where it is able to stimulate certain signaling cascades that assist in viral replication. Specifically, HIV attacks CD4 immune cells, which are a type of white blood cell that protects the body from infection. HIV viral cells have two molecules attached to its’ surface, GP120 and GP41 cells. GP120 binds to CD4 receptor cells; this causes conformational changes and spore formation that allow the virus to gain entry into the CD4 immune cells. Once in the cell, the viral genome is released and it is reverse transcribed into DNA by the viral enzyme, reverse transcriptase. The viral genome is then inserted into the host chromosome via the viral enzyme integrase. The DNA is transcribed and translated into proteins and exported out of the host cell via the vesicular sorting pathway. These new HIV viral particles are immature and noninfectious; therefore it cannot infect another cell (Simon, Ho & Karim, 2006). However, once the noninfectious HIV has left the host CD4 cell, the HIV releases protease, which breaks up longer protein chains within the noninfectious virus, thus forming the mature and infectious form of HIV (AidsInfo, n.d.).

</style>

Figure 5: Life Cycle of the HIV virus. Retrieved from: http://nigeriahivinfo.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/hiv-virus-life-cycle.jpg

Progression to AIDS

<style justify>

HIV will continue to proliferate within the body at low levels for many years. This chronic form of HIV will eventually become AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome). The progression of HIV to AIDS typically takes approximately 10 years or more, depending on the course of treatment. HIV damages the immune system so severely that the body is unable to fight off infections and the patient is thus diagnosed with AIDS. An individual must have a CD4 count of less than 200 cells/mm3 and/or have one or more opportunistic infections in order to be formally diagnosed with AIDS. Opportunistic infections are characteristic of individuals with extremely weakened immune systems and they are often associated with end stage HIV/AIDS (AidsInfo, n.d.).

</style>

Prognosis of HIV

<style justify>

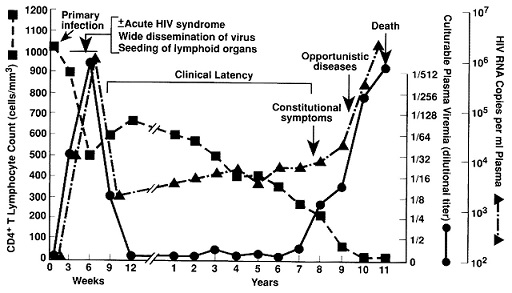

The timeline of an HIV infection begins at the acute stage, specifically known as “acute retroviral syndrome”, where the individual is first infected with the virus. They show no immediate symptoms, and two to four weeks later likely experience flu-like symptoms, of which include a fever, rash, muscle pain, and swollen glands. It is at this stage that the individual is at most risk of transmitting the virus to other people, as the viral load in their blood is at the highest level.

After the appearance of the flu-like symptoms, the viral particles then begin to reproduce at a very slow pace, and no longer aggravate any symptoms within the individual. This is the longest stage of the HIV infection, as it lasts an average of ten years. Certain factors do delay or accelerate the onset of AIDS, such as nutrition, genetic background, antiretroviral therapy (which will delay the onset of AIDS), and co-infection with other viruses (which will accelerate the onset of AIDS)

The final stage of the HIV infection is the onset of AIDS. As HIV is a virus that targets your CD4+ T cells, AIDS is diagnosed when the CD4+ T cell levels falls below 200 cells/mm3 of blood. This exposes the immune system, allowing for opportunistic infections to occur (“Stages of HIV infection”, 2015). The most common and severe infection to occur is pneumocystis pneumonia (“Fungal Diseases”, 2014) a fungal infection that causes fever, shortness of breath, fatigue, and a dry cough. Antibiotic treatment is used, as without proper treatment the mortality rate is closer to 100% (“Stages of HIV infection, 2015). Figure 6 (below) shows the general progression form HIV to AIDS, noting the gradual decline of CD4+ T cells, which is correlated to the increase in viral load at the onset of AIDS.

</style>

Figure 6: Progression of an HIV infection. Retrieved from http://annals.org/aim/article/709558/immunopathogenic-mechanisms-hiv-infection

Screening and Diagnosis

<style justify>

There is a wide range of tests done to screen someone for the presence of an HIV infection. The most commonly used procedure is an Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISA for short), which tests for antibodies present in the patients’ blood or oral fluid. First, a multi-well plate is filled with antigens, and then these wells are filled with the patients’ fluid sample. The wells are then washed out to remove any unbound antibodies, and an enzyme conjugate (specifically an animal immunoglobulin with an attached enzyme) is added, which will then bind to the specific antibody. The plate is washed out once more, and substrates that interact with the enzyme to produce colour are added to the wells. A coloured plate will therefore indicate an HIV positive test (“HIV Antibody Assays”, 2006). A person infected with HIV only produces a measurable amount of HIV antibodies three to twelve weeks post infection, so it is recommended that a person is retested 3 months after possible exposure, as screening during this “window period” will lead to a false negative (“HIV/AIDS Testing”, 2016).

A fourth generation assay, used by all laboratories across Canada, detects both HIV antibodies and the p24 antigen, a viral protein that composes the majority of the viral core (Wilton, 2015). It takes approximately two to six weeks for an individual to produce enough antibodies and antigens for a successful reading, therefore it is suggested that a re-test is done if the individual is tested during this period of time and receives a negative result (“HIV/AIDS Testing”, 2016). Two home tests are available on the market, the Home Access HIV-1 Test System and the OraQuick In-Home HIV test. The former test involves the individual pricking their finger to collect a blood sample and sending the sample to a laboratory. Their results are then processed as early as the following business day. The latter test is a home swab kit for oral fluid sample, and provides results within twenty minutes. A positive test will require a follow-up test at a clinic. Both tests detect HIV antibodies in the body fluids (“HIV Test Types”, 2015).

</style>

Transmission

<style justify>

The HIV virus is only transmittable through bodily fluids, specifically blood, semen, pre-seminal fluids, breast milk, and rectal and vaginal fluids. It is only spread through contact with mucosal membranes (via anal and vaginal membranes during sex), damaged tissues, and direct injection of the virus into the bloodstream (through sharing needles). It can also be spread from mother to child over the course of a pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding (“HIV Prevention”, 2016).

</style>

Figure 7: Modes of HIV transmission from human-to-human. Retrieved from: http://www.avert.org/hiv-transmission-prevention/how-you-get-hiv

Treatments

<style justify>

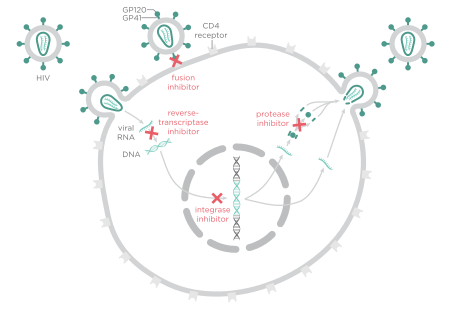

Currently, there is no cure for HIV/Aids, but medications are effective in fighting HIV and its complications. Most of the treatments are designed to reduce HIV in your body, keep your immune system as healthy as possible and decrease the complications you may develop. Several medications used for treatment have shown to slow down the growth of the virus or stop it from making copies of itself. Although these drugs don’t eliminate the virus completely from the body, they keep the amount of virus in the blow low. The amount of virus in the blood is called viral load and it can be measured by a test (Nordqvist, 2016).

There are several types of anti-HIV drugs and each type attacks the virus in its own way. Most people who are getting treated for HIV take 3 or more drugs. This is called combination therapy or “the cocktail”. Combination therapy is the most effective treatment for HIV (Robinson, 2016). HIV medicines have become much easier to take in recent years. Some of the newer drug combinations package three separate medicines into only one pill take once a day with minimal side effects. Most of the medications taken are tolerable and effective and let HIV-positive people live long and healthy lives although this is not the same case for every HIV patient it might be difficult for certain people to take the medication or cause some serious side effects (Robinson, 2016). It is possible for some of these drugs taken to become less effective overtime or stop working. Once the patient has taken the medication, they must discuss with their health care provider to monitor how well the medications are working and to find solutions for side effects (Nordqvist, 2016).

Earlier HIV Antiretroviral treatment

This treatment improves quality of life, extends life expectancy and reduces the risk of transmission according to the World Health Organization’s guidelines issued in 2013. When an HIV-positive adults CD4 cell count is 500 cells/mm3 or lower they should start treatment immediately (Nordqvist, 2016).

Figure 8: HIV Antiretroviral Treatment Retrieved from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d5/HIV-drug-classes.svg/450px-HIV-drug-classes.svg.png

Emergency HIV pills

If an individual believes that they have been exposed to the virus within the last 3 days (72 hours) anti-HIV medication called PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis) may stop the infection (Nordqvist, 2016). This treatment is very useful as it should be taken as soon as possible after contact with the virus. PEP is a very demanding treatment lasting about four weeks and it also includes side effects such as diarrhea, nausea, weakness and fatigue (Robinson, 2016).

Some of the drugs approved by the FDA for treating HIV and AIDs include:

Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NRTI)

· These drugs interrupt the virus from duplicating, which may slow the spread of HIV in the body. They do this by binding to the reverse transcriptase enzyme leading to its degradation. These include: · Abacavir · Didanosine · Emtricitabine · Lamivudine · Stavudine · Tenofovir · Zalcitabine · Zidovudine

Combinations of these NRTIs make it possible to take lower doses and maintain effectiveness (Nordqvist, 2016).

</style>

Fusion Inhibitors

Fusion inhibitors are new class of drugs that act against HIV by preventing the virus from fusing with the inside a cell, preventing it from replicating (Nordqvist, 2016). The group of drugs includes Enfuvirtide, also known as Fuzeon or T-20 (Nordqvist, 2016).

Non-Nucleoside Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitors (NNRTI)

Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) block the infection of new cells by HIV. These drugs may be prescribed in combination with other anti-retroviral drugs, Include: · Delvaridine · Efavirenz · Nevirapine (Robinson, 2016).

Current Research

<style justify>

As of November 2nd 2016, the first HIV Vaccine Trial has been initiated in South Africa, which has 7 million HIV-infected individuals, or one-fifth of the world HIV-positive population. Approximately 5400 men and women are enrolled in Phase III clinical trials of the HVTN (HIV Vaccine Trials Network) 702 vaccine (Surugue, 2016). The vaccine regimen actually consists of two different vaccines: the first is a canarypox-based vaccine, and the second is a bivalent GP120 subunit with an adjuvant to elicit an immune response. The canarypox-based vaccine is viral vaccine that elicits a cytotoxic T cell response towards HIV-infected cells. The bivalent GP120 vaccine with and adjuvant also helps boost the host's immune system by developing antibodies to recognize and remove viral particles if they enter the body. The type of GP120 subunit used is known to be associated with the strain of HIV that is the most prevalent in South Africa (“Large Scale HIV Vaccine Trial”, 2016). This provides the population with pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the the incidence and spread of HIV. The trial will last from November 2016 to December 2020 (Surugue, 2016).

</style>

References

<style justify>

- A Timeline of HIV/AIDS. (n.d.). Retrieved October 17, 2016, from https://www.aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/hiv-aids-101/aids-timeline/index.html

- AIDS.gov. (2015). HIV Test Types. Retrieved from https://www.aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/prevention/hiv-testing/hiv-test-types/AIDS.gov. (2015). HIV Test Types. Retrieved from https://www.aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/prevention/hiv-testing/hiv-test-types/

- AIDS.gov. (2015). Stages of HIV Infection. Retrieved from https://www.aids.gov/hiv-aids-basics/just-diagnosed-with-hiv-aids/hiv-in-your-body/stages-of-hiv/

- AIDSInfo. (2016). HIV Prevention. Retrieved from https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/education-materials/fact-sheets/20/48/the-basics-of-hiv-prevention

- AidsInfo. N.d. HIV Life Cycle. Retrieved from: https://aidsinfo.nih.gov/education-materials/fact-sheets/19/45/hiv-aids--the-basics

- Berger, E., Garrett, L., MacGregor, R. R., Vonmuller, E., Weiner, D. 2016. HIV and AIDS. Annenberg Learner. 91-106.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). HIV/AIDS Testing. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/testing.html

- Global HIV/AIDS Overview. (2016, September 28). Retrieved October 20, 2016, from https://www.aids.gov/federal-resources/around-the-world/global-aids-overview/index.html

- Hall, H., Geduld, J., Boulos, D., Rhodes, P., An, Q., & Mastro, T. et al. (2009). Epidemiology of HIV in the United States and Canada: Current Status and Ongoing Challenges. JAIDS Journal Of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 51(Supplement 1), S13-S20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/qai.0b013e3181a2639e

- Holland, K., & Krucik, G. (2013, July 12). The History of HIV. Retrieved October 17, 2016, from http://www.healthline.com/health/hiv-aids/history#EarliestCase1

- Large-Scale HIV Vaccine Trial to Launch in South Africa | NIH: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. (2016, May 18). Retrieved November 04, 2016, from https://www.niaid.nih.gov/news-events/large-scale-hiv-vaccine-trial-launch-south-africa

- Nordqvist, C. (2016, May 11). “HIV/AIDS: Causes, Symptoms and Treatments.” Medical News Today. Retrieved 26 October 2016, from http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/17131.php.

- Robinson, J. (2016). Understanding Treatment of AIDS/HIV. WebMD. Retrieved 26 October 2016, from http://www.webmd.com/hiv-aids/guide/understanding-aids-hiv-treatment?page=3

- Sharp, P. M., & Hahn, B. H. (2011). Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine, 1(1), a006841.

- Simon, V., Ho, D. D., Karim, Q. A. 2006. HIV/AIDS Epidemiology, pathogenesis, prevention and treatment. The Lancet, 368: 489-504.

- Surugue, L. (2016, November 2). First large-scale HIV vaccine trial in seven years to start in South Africa. International Business Times. Retrieved November 2, 2016, from http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/first-large-scale-hiv-vaccine-clinical-trial-seven-years-start-south-africa-1589468

- University of California San Francisco. (2006). HIV Antibody Assays. Retrieved from http://hivinsite.ucsf.edu/InSite.jsp?page=kb-02-02-01

</style>