This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Depression

<style justify> Depression is a commonly occurring form of mental illness that has a global impact on the individual, community and national level. Approximately 350 million people are thought to be affected to date and this number is expected to rise over the coming years. [16] The World Health Organization has classified it as the fourth leading cause of disability worldwide. [15] A sufferer experiences low mood and aversion to activity that can affect the individual's thoughts, behaviour and feelings and sense of wellbeing. These feelings of severe despair are experienced over an extended period of time and it is common for individuals with depression to simultaneously experience symptoms of anxiety. There are several efficacious and cost effective treatments available to date which range from generic antidepressant drugs to different forms of psychotherapy. Overall, depression is a heterogenous, burdensome disorder that exhibits a highly variable course, an inconsistent response to treatment and an incomplete understanding of the underlying neurobiology. </style>

History

The Ancient Greeks hypothesized that depression was caused by an imbalance of bodily fluid, or humor. The presence of different humors led to different dominant personalities. As such, an excess of bile resulted in melancholia - characterised by Hippocrates as a distinct disease, consisting of “fears and despondancies, if they last for a long time.” [14]

Physicians in the muslim and persian world developed ideas about depression in the Islamic golden age. The 11th century Persian physician Avicenna theorized that depression was a mood disorder in which sufferers become suspicious and develop phobias. Ishaq in Imran (d.908) associated depression with the inflammation of the brain and meninges. [10]

Various theories of melancholia flourished in medieval Europe, alongside the theories of Hypocrates, Avicenna and Galen. Acedia, or lethargy, was thought to be linked to be isolation. [14]

During the age of enlightenment (18th and 19th century) depression was thought be inheritable and untreatable weakness in temperament. Thus, depressed individuals were locked up in mental institutions and were subject to homelessness and poverty. [14]

Types and Symptoms

Major depressive disorder: also known as unipolar disorder; severe form of depression. A person with major depressive disorder has had at least one episode of severe depression that lasted almost everyday for at least two weeks. [3] During the episode, the individual has felt at least five of the following symptoms [1]:

- decreased interest in activities

- feelings of low self-esteem or guilt

- significant increase or decrease in weight or appetite

- excessive or insufficient sleep

- fatigue or loss of energy

- impaired concentration or decision–making

- speeded or slowed psychomotor activity

- thoughts of suicide

However, a person that experiences these symptoms within two months of bereavement does not have major depressive disorder.

Persistent depressive disorder: previously known as Dysthymic disorder [11]; mild, chronic form of depression. A person with persistent depressive disorder has experienced milder symptoms of depression, including [11]:

- increase or decrease in appetite

- feelings of low self-esteem or guilt

- impaired concentration or decision–making

- feeling of hopelessness

- insomnia or hypersomnia

The individual with persistent depressive disorder experiences these symptoms for most days for at least two years, with the symptoms being absent for no more than two months at once during that period.

Postpartum depression: may start during pregnancy or up to a year after the birth of the child. A mother or father with postpartum depression may not enjoy the baby and have frequent thoughts that they’re a bad parent. They may also have scary thoughts around harming themselves or their baby [5].

Bipolar I & II: also known as manic depression; when depression is accompanied with mania.

- A person with bipolar I disorder has experienced at least one manic or mixed episodes. In the manic episode, one experiences at least three of the following symptoms for at least a week: delusional self-esteem, low need for sleep, increased talkativeness, poor judgment, and distractibility with many thoughts. In the mixed episode, one experiences symptoms of both major depressive disorder and manic episodes for at least a week.[2]

- A person with bipolar II disorder has experienced at least one major depressive episode and one hypomanic episode. The hypomanic episode lasts for at least four days and has same but less severe symptoms of manic episode.[4]

Cyclothymic disorder: mild, chronic form of Bipolar disorder. A person with cyclothymic disorder experiences both hypomanic episodes and milder symptoms of major depressive disorder for most days for at least two years, with the symptoms being absent for no more than two months at once during that period [6].

Risk Factors

Almost all community epidemiological studies find that gender, age, and marital status are associated with depression [12]. Depression usually presents during the teens, 20s and 30s in both men and women. Women are two times more likely to be diagnosed with depression, but it is still not yet clear whether this is in part due to women being more likely to seek treatment. Individuals who are separated or divorced have significantly higher rates of major depression than the currently married and prevalence of major depression generally goes down with age.

Factors that seem to increase the risk of developing or triggering depression include [8]:

- Personality Traits e.g. pessimism, low self-esteem, self criticism

- Traumatic events (PTSD, death of a loved one, sexual abuse etc.)

- Drug abuse

- History of mental health disorders

- Family history and genetic factors

- Other chronic illness e.g. cancer, heart disease, chronic pain

- Certain prescription drugs

Pathophysiology

The limbic brain regions associated with mood and depression include the hippocampus and the prefrontal cortex. Studies suggest that stress and depression are associated with atrophy and loss of neurons and glia, which contribute to the decreased size and function of these brain areas. There are two main hypotheses for the underlying mechanism of depression.

<style justify> The Monoamine-deficiency hypothesis: The first real indication that depression might result from a problem with the central nervous system modulatory systems came in the 1960s. A drug called reserpine, introduced to control high blood pressure, caused psychotic depression in about 20% of cases. Its mechanism of action involves the depletion of central catecholamines and serotonin by interfering with their loading into synaptic vesicles. Another class of drugs introduced to treat tuberculosis caused a marked elevation in mood. These drugs inhibit monoamine oxidase (MAO) which is the enzyme that degrades catecholamines and serotonin in the synaptic cleft. Furthermore, when it was discovered that the drug imipramine, introduced as an antidepressant years earlier, inhibits the reuptake of released serotonin and norepinephrine, thus promoting their action in the synaptic cleft. As a result of these observations, researchers developed the hypothesis that mood is closely tied to the levels of released monoamine neurotransmitters, norepinephrine and/or serotonin, in the brain. According to this monoamine hypothesis, depression is a consequence of a deficit in one of these diffuse modulatory systems [7]. </style>

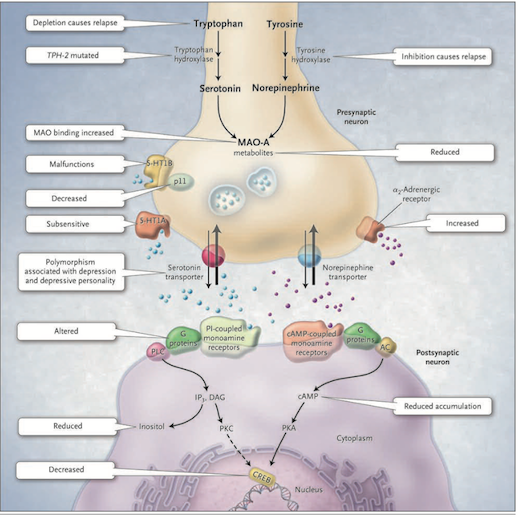

Figure 1: The Monoamine-deficiency hypothesis (Source: Bedmaker & Agam, 2008) </style>

<style justify> This hypothesis postulates a deficiency in serotonin or norepinephrine neurotransmission in the brain. Serotonin is synthesized from tryptophan by the enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase; norepinephrine is synthesized from tyrosine which is catalyzed by the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase. Both monoamine transmitters are stored in vesicles in the presynaptic neuron and released into the synaptic cleft, thereby affecting both presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons. Neurotransmission is mediated by serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine 1A [5-HT1A] and 5-hydroxytryptamine 1B [5-HT1B]) or norepinephrine receptors [7].

There are several mechanisms by which the activity of these neurotransmitters can be terminated. One possibility is through reuptake through the specific serotonin and norepinephrine transporters and by feedback control of release through the presynaptic 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B regulatory autoreceptors for serotonin and the α2-noradrenergic autoreceptors for norepinephrine. Monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A) catabolizes monoamines presynaptically and thereby indirectly regulates vesicular content. The function of the 5-HT1B receptor is increased by the p11 protein and therefore a decrease in this p11 protein is thought to be implicated in depression [7].

On the postsynaptic neuron, serotonin and norepinephrine bind G-protein coupled receptors including the cyclic AMP (cAMP)-coupled receptor and the phosphatidylinositol-coupled receptor. The downstream effects of the cAMP-coupled receptor are to activate adenylyl cyclase which generates cAMP which in turn activates protein kinase A (PKA). The phosphatidylinositol pathway activates phospholipase C which generates two second messengers, IP3 (activates Ca2+ release) and diacylglycerol (activated protein kinase C (PKC)). The two protein kinases affect the cAMP response element–binding protein (CREB). Findings in patients with depression that support the monoamine-deficiency hypothesis include a relapse of depression with inhibition of tyrosine hydroxylase or depletion of dietary tryptophan, an increased frequency of a mutation affecting the brain-specific form of tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH-2), increased specific ligand binding to MAO-A, subsensitive 5-HT1A receptors, malfunctioning 5-HT1B receptors, decreased levels of p11, polymorphisms of the serotonin-reuptake transporter associated with depression, an inadequate response of G-proteins to neurotransmitter signals, and reduced levels of cAMP, inositol, and CREB in postmortem brains [7] [Figure 1]. </style>

<style justify> The Diathesis-stress hypothesis: According to this hypothesis, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the main site where genetic and environmental influences converge to cause mood disorders. As mentioned earlier, depression can run in families and our genes can predispose us to mental illness. Furthermore, early childhood abuse or neglect, and other stresses of life, are important risk factors in the development of depression in adults. Hyperactivity of the HPA axis results in elevated blood cortisol levels as well as higher concentrations of corticotropin-releasing hormone in the cerebrospinal fluid. Injected CRH into the brains of animals produces behavioural effects that are similar to those of major depression: insomnia, decreased appetite, decreased interest in sex and increased behavioural expression of anxiety.[7] </style>

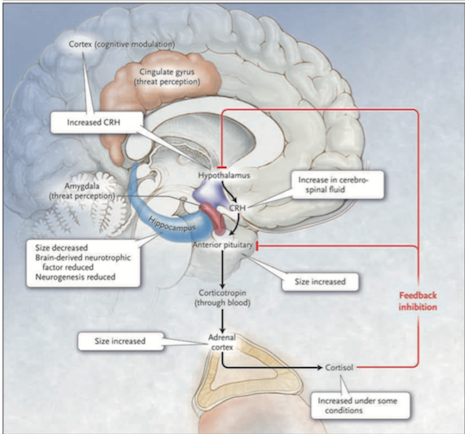

Figure 2: The HPA system in depression (Source: Bedmaker & Adam, 2008) </style>

<style justify> Abnormalities in the cortisol response to stress may underlie depression. The black arrows in Figure 2 show that in response to stress, which is perceived by the brain cortex and the amygdala and transmitted to the hypothalamus, corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) is released. This induces the anterior pituitary gland to secrete corticotropin into the bloodstream. Corticotropin stimulates the adrenal cortexes to secrete the glucocorticoid hormone cortisol. The red line in Figure 2 shows that cortisol, in turn, induces feedback inhibition in the hypothalamus and the pituitary, suppressing the production of CRH and corticotropin, respectively. Activation of hippocampal glucocorticoid receptors by cortisol normally leads to feedback inhibition of the HPA axis. In depressed patients this feedback is disrupted thus leading to the hyperactivation of HPA. A molecular basis for the diminished hippocampal response to cortisol is a decreased number of glucocorticoid receptors. The number of receptors is regulated by genes, monoamines and early childhood experiences. Findings in patients with depression that support the hypothalamic–pituitary–cortisol hypothesis include the following: cortisol levels are sometimes increased in severe depression, the size of the anterior pituitary and adrenal cortex is increased, and CRH levels in the cerebrospinal fluid and CRH expression in the limbic brain regions are increased. Furthermore, hippocampal size and the numbers of neurons and glia are decreased, possibly reflecting reduced neurogenesis due to elevated cortisol levels or due to reduced brain-derived neurotrophic factor. [7] </style>

<br> <br> <br> <br> <br> <br> <br> <br> <br> <br>

Treatment

There are several known, effective treatments for depression that vary from medicinal to psychological in nature. Despite these known methods, fewer than half of those affected in the world receive them. Barriers to effective care include a lack of resources, misdiagnosis, a lack of trained health care providers, and social stigma associated with mental disorders. [12]

Antidepressant: Two of the major classes of drugs used to treat this disorder are Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) and Serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). The mechanisms of these drugs are described below.

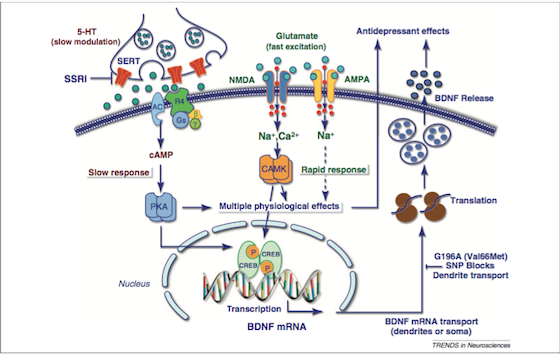

SSRIs: As the name suggests, these drugs prevent the reuptake of serotonin. They do this by inhibiting a monoamine transporter protein, SERT [Figure 3], that transports serotonin from the synaptic cleft to the presynaptic neuron. The SSRIs block the reuptake of serotonin, leading to increased concentrations of the neurotransmitter in the synaptic cleft [Figure 3] and, ultimately, to greater postsynaptic neuronal activity. SSRIs are actually a “successor” to SNRIs, as they are “selective” to serotonin, and usually do not affect other hormones in the nervous system. They are by far the most common drugs prescribed. Some examples of SSRIs include: Fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), and citalopram (Celexa). Side effects include: Sexual Dysfunction, Sleep Disorders, and headaches if treatment is suddenly stopped [13].

<html>

Figure 3: Signalling pathways and the treatment of depression (Source: Duman & Voleti, 2012)

</style>

<style justify> SNRIs: Like SSRIs, SNRIs prevent the reuptake of serotonin by inhibiting the activity of neurotransmitters. Unlike SSRIs, SNRIs also prevent the reuptake of the neurotransmitter Norepinephrine. These can be thought of as the less refined predecessor to SSRIs. Another class of antidepressants, known as tricyclic antidepressant (TCAs), also act in the same way as SNRIs. [13]

Psychotherapy: In the clinic, psychotherapy is often used as an alternative or in conjunction to pharmacological treatment. The main forms of psychotherapy used are cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT).

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT): CBT is founded on the principle that initial thoughts and perspectives are the root of associated behaviour. In CBT, the psychotherapist and patient work together to determine the patterns and markers of detrimental thought patterns. The focus on thought patterns allow it to be used to deal with the feelings of worthlessness in depression.[9]

Interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT): IPT is based on the principle that depressive symptoms are influenced by the relationships the patient holds with other people. The therapy acts to identify and analyze how disruptions in a patient’s relationship with another party plays a role in their behaviour. For example, the challenges of pregnancy often put a strain on the relationship between the new mother and the relationship with her spouse. The economic and personal challenges of having a child may affect the relationship between the new parents, and lead to depressive symptoms in the mother (or even father). Interpersonal therapy analyses relationships from the perspectives of

attachment, communication, and social importance. [9]

</style>

References

[1] American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

[2] Anderson, IM, Haddad, PM, Scott, J (2012). Bipolar disorder. BMJ (Clinical research ed.) 345: e8508. doi:10.1136/bmj.e8508. PMID 23271744.

[3] Belmaker, R.H. and G. Agam (2008): Major depressive disorder. N. Eng. J. Med 358: 55-68.

[4] Benazzi, F. (2007). Bipolar II disorder. CNS drugs, 21(9), 727-740.

[5] Canadian Mental Health Association. (2016). Postpartum Depression. Retrieved 24 January, 2016, from https://www.cmha.ca/mental_health/postpartum-depression/

[6] Drevets, W. C., & Todd, R. D. (2005). Depression, Mania, and Related Disorders.

[7] Duman, R & Voleti, B. (2012). Signaling pathways underlying the pathophysiology and treatment of depression: novel mechanisms for rapid-acting agents. Trends in Neurosciences, 35(1), 47-56.

[8] Fast Facts About Mental Illness. (2015). Retrieved January 26, 2016, from http://www.cmha.ca/media/fast-facts-about-mental-illness/#.

[9] Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The Efficacy of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: A Review of Meta-analyses. Cognitive therapy and research. 2012;36(5):427-440. doi:10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1.

[10] Jacquart D. “The Influence of Arabic Medicine in the Medieval West” in Morrison & Rashed 1996, pp. 980

[11] John M. Grohol, Psy.D. (2013). DSM-5 Changes: Depression & Depressive Disorders. Psych Central.

[12] Kessler, R. C., & Bromet, E. J. (2013). The epidemiology of depression across cultures. Annual Review of Public Health, 34, 119–138. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114409

[13] Marken PA, Munro JS. Selecting a Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor: Clinically Important Distinguishing Features. Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2000;2(6):205-210

[14] Radden, J (March 2003). “Is this dame melancholy? Equating today's depression and past melancholia”. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology 10 (1): 37–52. doi:10.1353/ppp.2003.0081.

[15] World Health Organization. (2008). The Global Burden of Disease 2004 update. Retrieved 24 January, 2016, from http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GBD_ report_2004update_full.pdf

[16] World Health Organization. (2015). Depression Fact Sheet. Retrieved 24 January, 2016, from http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/