Table of Contents

Presentation Slides

Music Therapy

“Music therapy is a discipline in which credentialed professionals (MTA*) use music purposefully within therapeutic relationships to support development, health, and well-being. Music therapists use music safely and ethically to address human needs within cognitive, communicative, emotional, musical, physical, social, and spiritual domains.”

CAMT. (n.d.)

Development of Music Therapy

- At the end of World War II, music therapy was used to help returning soldiers recover from physical and mental injuries.

- Music therapy research was also conducted for many years to prove its validity.

- In 1974, Canadian Association for Music Therapy (CAMT) was created.

Music Therapy Models

The Nordoff-Robbins approach - Creative Music Therapy

A music-centered, humanistic approach developed by Paul Nordoff (American Composer) and Clive Robbins (British special educator). They believed that within each one of us is a “music child”, meaning regardless of diagnoses the ability to engage in music remains healthy and able to engage with others. In this approach, one therapist is playing an instrument, while the second therapist is with the child, helping them play their instrument. The music therapists need to be accomplished musicians and flexible with the music in this approach.

BioMedical Models

Music is Biopsychosocial; it has an impact on us biologically through the release of hormones (endorphins) as well as emotionally, psychologically through the evocation of memories, and socially bringing people together.

Neurologic Music Therapy (NMT)

Requires extra training after post standard music therapy training. This additional training is also available to physiotherapists. This approach of Music Therapy focuses on using aspects of music to facilitate movement through standardized interventions. Common uses of this approach are for rehabilitation post car accident, post-stroke, and with Parkinson's Disease.

Aesthetic Music Therapy

Music is integral to the session and it must sound good. The goal of these therapists are to surround the music being played by the client with music that compliments the sound, to make an aesthetically sounding/pleasing improvisation.

Behavioural model

Using music as a reward or consequence. This method is used predominantly in the United States, it is results driven, where the therapist leads the session and the client to change behaviour. For example, music can be used as a reward to reduce a certain behaviour.

Cognitive Behaviour Music Therapy (CBT)

This approach involves providing new experiences for the client to help them shift their perspective, for example reframing a negative situation they were in into a positive experience. The goal is for the client to take the skills of reframing learned in the session and transition it’s use into everyday life as well. It especially useful for clients with anxiety, as they practice transforming bad situations to good ones. Music Therapy sessions are a safe place to improvise and reinforce that it's okay to take a risk, and provide opportunities to have a good experience.

Free improvisation model

In this model, the client makes up music on the spot by singing or by using an instrument within the moment. As a result, they are able to create a rhythm, melody, and a song. During the process, the music therapist does not implement any rules and allows the client to improvise freely (Bruscia, 1988). It helps the client explore their mood and encourages social skills and interaction. Within this model, goals include verbal communication, self-expression, group skills, creativity, and cognitive skills (Bruscia, 1988). This model is used for many clients including those with neurological damage, mental health conditions, anxiety, and autistic spectrum disorders (Macdonald & Wilson, 2014).

Analytically-oriented music therapy model

This model was created by Mary Priestly. This model includes approaches that places the ‘unconscious’ as the basis of emotional disturbance. In this model, the music therapy aims to explore hidden motivations and feelings of the client. In this model, the client and the music therapist creates music together to externalize their internal feelings and experiences (Wingram, Pedersen, & Bonde, 2002). Music therapists believe that making music by using instruments allows one to freely express their emotions such as anger without guilt. Afterwards, there is dialogue between the music therapist and client revolves around dreams and fantasies to explore the conscious and unconscious states of the client (Wingram, Pedersen, & Bonde, 2002).

Eclectic Approach

In this model, music therapists uses methods from various types of therapies as they believe no single theory is adequate for complexities of human behaviours. This is to customize the therapy to efficiently meet the specific goals and needs of the clients. The frameworks behind the theories are not analyzed in this model (Arnold, 2015) but is simply used. By using a combination of models, clients are able to reflect upon themselves and their abilities. The eclectic approach can treat individuals with addictions, substance abuse disorders, eating disorders, mood disorders, etc. (Arnold, 2015).

Music Therapy Techniques

Instrumental music playing

In this model, the client actively participates by playing an instrument. It is believed that this helps refine the client’s motor skills and muscle control. It also helps with motion, endurance, strength, hand movements, finger dexterity, and other functional movements (Thaut, 2008).

Lyric analysis

In this model, song lyrics are used to promote meaningful discussion in individual or group music therapy. It can provide a sense of normalcy, and to comprehend death, loss and pain in a more comfortable method (Ellis, 2016). The songs can be selected by the client or it can be a contemporary song. The idea is that analyzing lyrics of a song allows the client to reflect on how they view themselves in the world and how they are feeling (Ellis, 2016).

Songwriting

Songwriting is an intervention that has been gaining popularity in the music therapy research over the past twenty years. Research by Baker et al. (2008) explores the trends in the clinical practice of songwriting. A survey was implemented involving nearly twenty questions and were given to 477 professional music therapists practicing in 29 countries (Baker et al., 2008) and studied. The qualitative data indicated that songwriting was often utilized in developmental disability and autism spectrum disorder systems. In addition to this, the survey ascertained that the most repeatedly identified skill development were “experiencing mastery, develop[ing] self-confidence, enhance[ing] self-esteem, choice and decision making,…[and] gaining insight or clarifying thoughts and feelings” (Baker et al., 2008).

With respect to autism, specifically Asperger’s Syndrome, research has indicated that children with the condition are naturally drawn attracted to technology; as such, researchers have “[taken] advantage of this fascination” (Baker et al., 2009) and used songwriting as an apt virtual intervention (i.e. via Skype). Use of computers have been beneficial in skill development, such as acknowledging and guessing outcomes of human feelings. Furthermore, children’s critical thinking and language development were also positive outcomes of using such an intervention. To assist the researchers in identifying further benefits of songwriting, a list of 10 codes were developed (including “confirming statements, disagreeing statements, head nodding, smiling/laughing, etc.). These codes were used by the therapists to develop transcripts of how a music therapy session went and for researchers to analyze client engagement levels. This study concluded that using on-line video technology was a viable means of “[implementing] online music therapy with…client[s]” (Baker et al., 2009).

Singing

“Singing, or the act of producing musical sounds with the voice, has the potential to treat speech abnormalities” as it invariably invigorates the muscle systems related with “respiration, phonation, articulation, and resonance” (Wan et al., 2010). Singing is generally comprised of relatively powerful and quick inhalations in addition to longer exhalations. Furthermore, development of the art contributes to maturation of vocal strength, which is inhibited in some neurological conditions, such as Parkinson’s disease. Additionally, “it has been suggested that singing increases respiratory muscle strength” (Wan et al., 2010).

Stuttering is a progressive speech condition which impacts the articulacy of communication. It can be described as a “repetition of words or parts of words, as well as prolongations of speech sounds,” (Wan et al., 2010) which contributes to interruptions in the regular pace of dialogue. This disorder often takes place in childhood and youth, while voice and literacy skills are gained. In fact, “1% of adults continue to be affected by this condition” (Wan et al., 2010). Neuroimaging reports assessed affected individuals with a control group. By means of a positron emission tomography (PET), researchers studied brain stimulations connected with activities that induce better articulacy and fluency. For example, singing takes place with a fluency-inducing tasks (e.g. with a metronome: a device that provides an external, controlled tempo) versus tasks that are conducive to less organization and assistance in word formation. Specifically, The areas of the brain which were substantially more operational during fluency-inducing tasks compared to the opposing group “included auditory areas that process speech and receive sensory feedback as well as motor and premotor regions that are involved in articulatory motor actions” (Wan et al., 2010). This insinuates that there is a mechanism involving the auditory motor that may trigger stuttering. The fluency inducing activities caused stronger stimulation within the left hemisphere of the stuttering group; this may imply reimbursing neurological activities that enable fluidity in speech (Wan et al., 2010).

Biology of How Music Therapy Impacts Pain Perception

Pain

Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage. On the other hand, nociception is the biological event of pain. Nevertheless, pain is an emotional response as a result of nociception. Pain is not just a physical sensation, but it is influenced by attitudes, beliefs, personality, and social factors. These influences nevertheless have the ability to affect one's emotional and mental wellbeing. The experience of pain is highly subjective; therefore, it can vary greatly from person to person. There are many studies that supports the use of music listening to assist with pain management, using brain imaging (fMRI, PET).

Neurotransmitters

Neurotransmitters that mediate pain (and emotions) include:

- norepinephrine

- dopamine

- melatonin

- epinephrine

- L-dopa

- serotonin

- prolactin

- enkephalins.

Studies measuring hormone levels in the blood have shown an increase in serotonin, which inhibits pain, and dopamine, which causes pleasure, following music therapy

How can music modify pain?

Exact mechanisms still remain unclear as to why music may affect pain perception; however, music can modify pain in the following ways:

Affective (pertaining to emotions)

- Music facilitates a sense of control over pain (Linnemann et al. 2015; Mitchell & MacDonald, 2006).

- Additionally, it has the ability to reduce pain perception by reducing stress (Linnemann et al. 2015).

Cognitive (pertaining to distracting stimulus)

- “Gate control theory” (Melzack & Wall, 1965)

- Music evokes emotions and memories that distract from the pain.

Sensory

- Music and pain travel along the same biological pathway

- Music can elicit physiological responses such as the release of endorphins that counteract pain (Beaulieu-Boire et al. 2013).

Entrainment

- Music can induce relaxation through entrainment effects to slow breathing and heartbeat (Bradt, 2010).

Music Therapy Interventions for Pain

Instrument playing

When clients use instrument playing during music therapy sessions, there are many advantages. This includes improving one’s own wellbeing, feeling that you belong to a part of something and obtaining the ability to express oneself. This overall leads to less pain (Finnerty, 2006).

Activities with Rhythm

Advantages of using rhythm for music therapy clients include the ability for the rhythm to regulate breathing, regulate heart rate, and overall causing relaxation. This relaxation is nevertheless correlated to reduced pain (Finnerty, 2006).

Improvising

Benefits of improvisation during music therapy sessions include the presence of meaningful interpersonal contact and expression between the client and the music therapist. During improvisation, researchers also predict that endorphins are being released. As a result, pain perception is decreased after the release of endorphins and after the release of emotions from improvising (Finnerty, 2006).

Listening

When clients listen to meaningful music during music therapy sessions, this music can prompt happy memories and evoke emotions. This is nevertheless associated with the limbic system. As a result, the perception of pain decreases as happy feelings overrules pain (Finnerty, 2006).

Composing

When a music therapist and a client composes music together, the client is able to share their feelings and experiences through the music. Additionally, endorphins are released in the body. Again, this is associated with the limbic system. Consequently, pain perception decreases as emotions are being released and endorphins are increased (Finnerty, 2006).

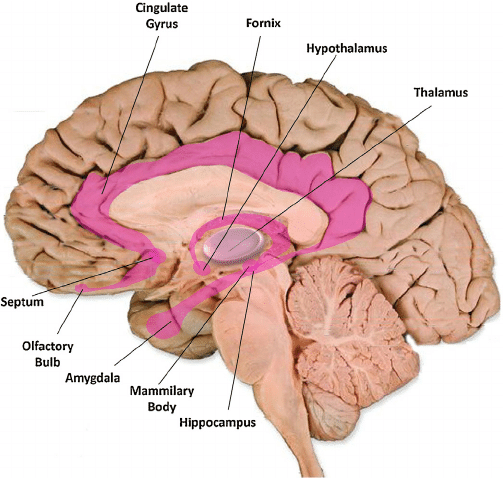

Limbic System

The limbic system consists of a complex set of structures largely responsible for emotional states. Areas in the limbic system are activated during music listening and in music therapy sessions. During music therapy sessions, endorphins are released which make clients feel better and reduce pain perception.

Hypothalamus

According to Finnerty (2006), the hypothalamus regulates responses to pain and pleasure, in addition to hunger, thirst, anger, etc. In relation to pain, the fight or flight response is managed by the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system. An increase in pain also correlates to increased heart rates, blood pressure, and breathing (Finnerty, 2006).

Hippocampus and Mammillary body

The hippocampus and the mamillary body is involved in forming memories and converting short term memories to long term memories (Finnerty, 2006). Memories nevertheless causes pain in an individual. Music therapy has the opportunity to stimulate pleasurable memories to override the painful memories (Finnerty, 2006).

Nucleus Accumbens

The nucleus accumbens is involved in reward, pleasure, and addiction, In relation to pain, it has the ability to block the systems involved in pleasure and reward. Music therapy possesses the opportunity to stimulates pleasure; thus, distracting the feelings of pain (Finnerty, 2006).

Orbitofrontal cortex

The orbitofrontal cortex is responsible for decision-making. Pain causes a lack of motivation for making good decisions (Finnerty, 2006). Music therapy, however, has the ability to increase one’s self-confidence and motivation which nevertheless improves better decision-making (Finnerty, 2006).

Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA)

The ventral tegmental area is the part of the limbic system involved in pleasure due to the dopamine pathway. Analgesics, or pain relievers, has the ability to increase dopamine levels, thus decreasing pain (Finnerty, 2006). Music therapy can also have similar effects. Music therapy has the ability to increase dopamine and decrease the extent of pain as well (Finnerty, 2006).

Studies

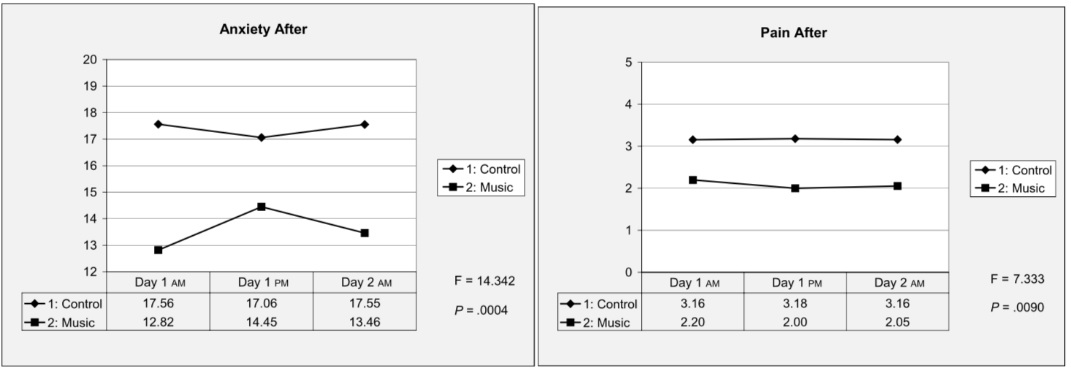

Physiological and psychological Outcomes in Cardiac Patients

Cardiac surgeries have been found to instigate various mechanisms relating to pain and anxiety, especially after surgeries have taken place. This research study is introductory which reveals that there is a positive relationship between using music therapy and encouraging physiologic and psychological results for cardiac patients.

The Gate Control Theory supports the idea that pain stimuli are conducted originating from the “nerve receptor to synapses in the gray matter (the substantial gelatinosa) of the dorsal horns of the spinal cord” (Sendelbach et al., 2006). Such synapses play the role of “gates” which become compact to prevent stimuli from going to the brain or “open to allow the impulses to ascend and therefore reach higher levels of conscious awareness of pain” (Sendelbach et al., 2006). Other sensory impulses may inundate these gates depending on whether or not these gates are open. In the case of using music therapy as a means to reduce pain, the use of guided imagery by patients acts as sensory input which may be adequate to close the pain-inducing pathway.

Sendelbach and colleagues studied whether music therapy during postoperative recovery periods contributed to a reduction in “anxiety, pain levels, HR and BP”. Both anxiety and pain levels were measured using a scale ranging from 0 to 10. Heart rate, a physiological parameter, was non-invasively measured using a bedside monitor; likewise, the blood pressure was measured. There were significant decreases in all four parameters, having measured them before and after music therapy. The interventions used included music selection and listening.

Oncology And Palliative Care Pilot Study

This pilot study consisted of oncology and palliative care subjects in a hospital pilot program at the Royal Melbourne Hospital. After undergoing music therapy, 89% of patients found music therapy either “extremely helpful” or “helpful” in reducing pain perception (with over half of those responding with “extremely helpful”)

References

Arnold, M. (2015). What Is Eclectic Therapy? Retrieved from https://www.crchealth.com/types-of-therapy/what-is-eclectic-therapy/

Baker, F., & Krout, R. (2009). Songwriting via Skype: An online music therapy intervention to enhance social skills in an adolescent diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome. British Journal of Music Therapy, 23(2), 3-14.

Baker, F., Wigram, T., Stott, D., & McFerran, K. (2008). Therapeutic Songwriting in Music Therapy: Part I: Who Are the Therapists, Who Are the Clients, and Why Is Songwriting Used?. Nordic Journal of Music Therapy, 17(2), 105-123.

Beaulieu-Boire, G., Bourque, S., Chagnon, F., Chouinard, L., Gallo-Payet, N., & Lesur, O. (2013). Music and biological stress dampening in mechanically-ventilated patients at the intensive care unit ward—a prospective interventional randomized crossover trial. Journal of Critical Care, 28(4), 442-450. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.01.007

Bruscia, K. (1988). A Survey of Treatment Procedures in Improvisational Music … Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0305735688161002

Bradt, J., Magee, W. L., Dileo, C., Wheeler, B. L., & Mcgilloway, E. (2010). Music therapy for acquired brain injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd006787.pub2

CAMT. (n.d.). About Music Therapy. Retrieved April 3, 2019, from https://www.musictherapy.ca/about-camt-music-therapy/about-music-therapy/

Ellis, A. (2016). Lyric Analysis. Retrieved from http://blogs.cuit.columbia.edu/are2126/2016/12/02/lyric-analysis/

Finnerty, R. (2006, November). Music Therapy as an Intervention for Pain Perception. Retrieved April 2, 2019, from http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.530.5016&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Linnemann, A., Kappert, M. B., Fischer, S., Doerr, J. M., Strahler, J., & Nater, U. M. (2015). The effects of music listening on pain and stress in the daily life of patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9. doi:10.3389/fnhum.2015.00434

Macdonald, R. A., & Wilson, G. B. (2014). Musical improvisation and health: A review. Psychology of Well-Being,4(1). doi:10.1186/s13612-014-0020-9

Melzack, R., & Wall, P. D. (1965). Pain mechanisms: A new theory. Science, 150(3699), 971-9, 3-11.

Mitchell, L. A., & Macdonald, R. A. (2006). An Experimental Investigation of the Effects of Preferred and Relaxing Music Listening on Pain Perception. Journal of Music Therapy, 43(4), 295-316. doi:10.1093/jmt/43.4.295

Sendelbach, S. E., Halm, M. A., Doran, K. A., Miller, E. H., & Gaillard, P. (2006). Effects of music therapy on physiological and psychological outcomes for patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Journal of cardiovascular nursing, 21(3), 194-200.

Thaut, M. H. (2008). Rhythm, music, and the brain: Scientific foundations and clinical applications. New York: Routledge.

Wan, C. Y., Rüüber, T., Hohmann, A., & Schlaug, G. (2010). The therapeutic effects of singing in neurological disorders. Music perception: An interdisciplinary journal, 27(4), 287-295.

Wigram, T., Pedersen, I. N., & Bonde, L. O. (2002). A comprehensive guide to music therapy: Theory, clinical practice, research, and training. London: Jessica Kingsle