Table of Contents

Melanoma

Introduction

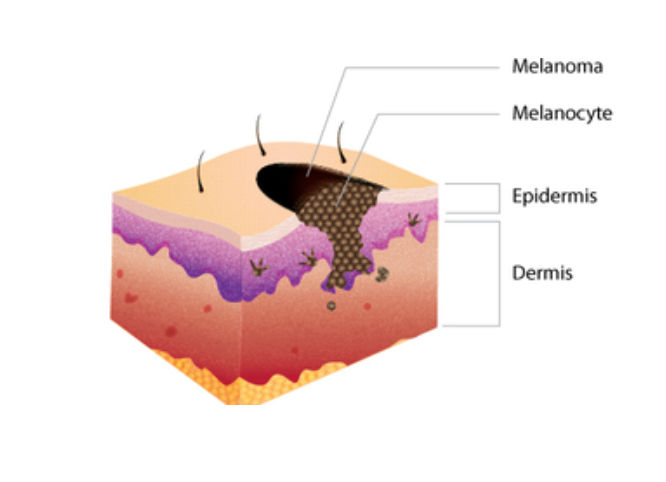

Melanoma is one specific type of skin cancer. It starts in the cells of the skin called melanocytes, which make the pigment melanin (“What is melanoma skin cancer”, 2018). Melanin is a critical pigment produced by the body which gives hair, eyes, and skin their respective colours. In a person with melanoma, skin cells, specifically melanocytes, multiply swiftly to form a cancerous tumor, or multiple cancerous tumours (“What is melanoma skin cancer”, 2018). Although melanoma usually begins in the skin, it can quickly spread to other parts of the body, including vital organs and bones. For example, in patients diagnosed with melanoma, it has commonly spread to the brain, liver and lungs, among other organs (“Metastatic Melanoma”, 2018). Melanoma typically develops as moles on the surface of the skin (“Skin Cancer Melanoma”, n.d.).

Incidence

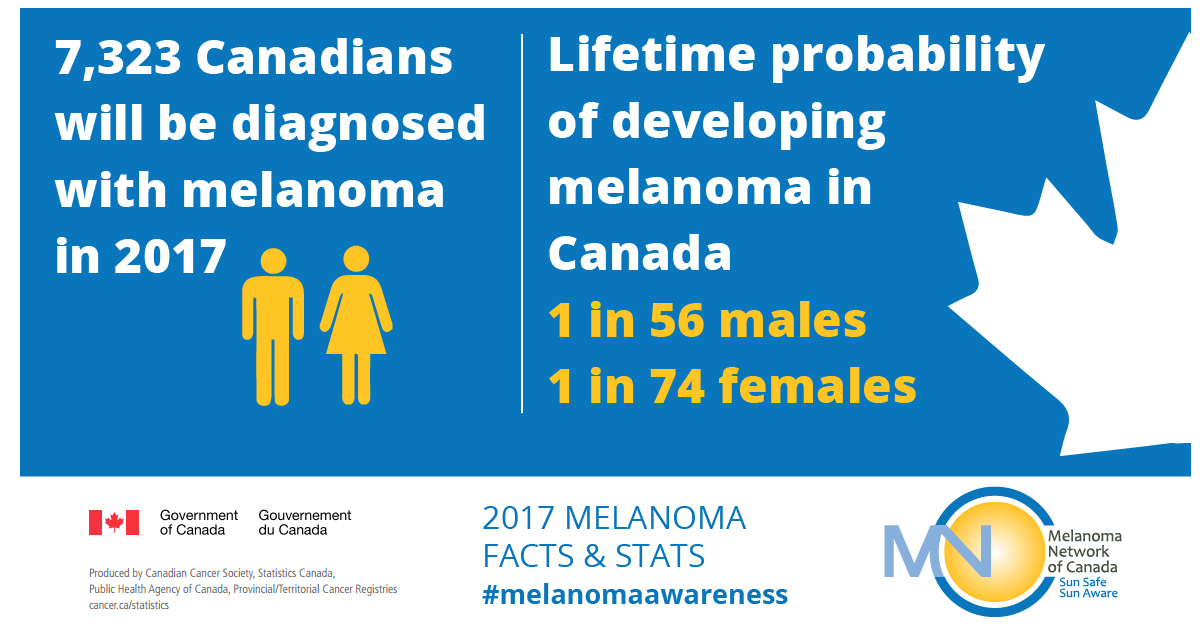

Melanoma is one of the most common forms of cancer in Canada. In fact, according to the Canadian Cancer Society, it ranks as the seventh most common cancer in Canada (“Melanoma skin cancer statistics”, 2017). Unfortunately, unlike other cancers where the incidence rate is decreasing, the incidence rate for melanoma is actually increasing. In fact, in many developed countries, it has increased faster than any other cancer since the 1950’s. In fact, in Canada in 2017 alone, 7,200 people were diagnosed with it, and 1,250 people died from it (“Melanoma skin cancer statistics”, 2017). Globally, approximately 132,000 cases of melanoma are diagnosed each year (WHO, 2018). There may be various reasons why the incidence rate of melanoma is increasing. For one, doctors have become better at detecting this cancer. In addition, the increase in the incidence rates of this cancer can be attributed to the use of tanning beds by many people, which emit ultraviolet radiation, shown to increase the chances of melanoma (“Why melanoma skin cancer is increasing“, 2017).

Distribution

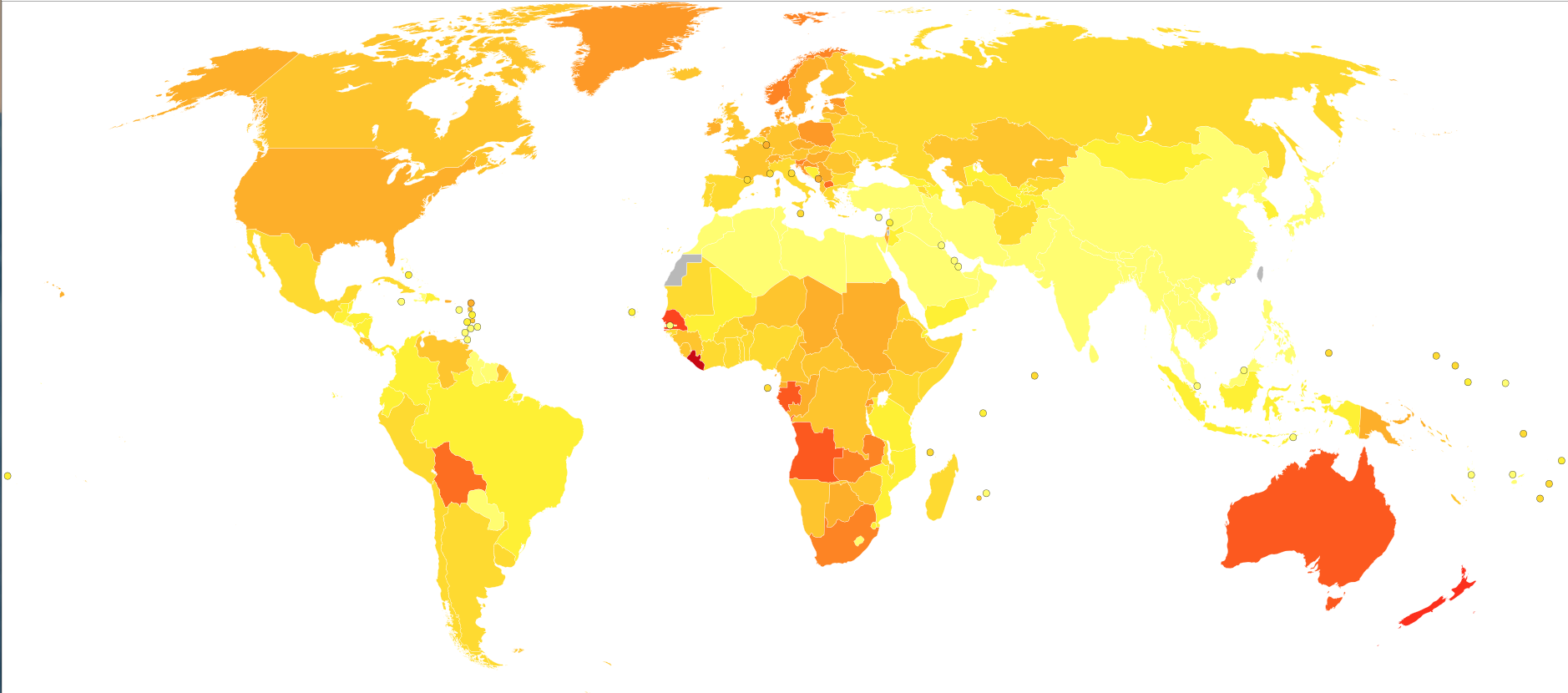

Worldwide, melanoma makes up 1.7% of all cancer cases diagnosed (“Worldwide cancer data”, 2018). However, the distribution of melanoma is not equal throughout the world. According to a recent study, melanoma predominantly affects residents from Australasian countries such as Australia and New Zealand, as well many European countries (Karimkhani et al., 2015). There are a few reasons for this discrepancy in melanoma cases between these parts of the world and others. One reason is because melanoma predominantly affects fair skinned people, and many residents of these areas possess fair skin (Karimkhani et al., 2015). Another reason for the increased rates of melanoma may be because these countries typically have higher levels of ultraviolet radiation, a common characteristic that causes melanoma (Karimkhani et al., 2015).

Survival Rates

Fortunately, melanoma has one of the highest rates of survival, among any form of cancer, especially if it is caught early (Melanoma, n.d.). However, if the cancerous cells proliferate to other parts of the body and affect vital organs, it becomes very difficult to treat. If a patient is diagnosed quickly, and the melanoma is only in its early stages, the survival rate may be as high as 97% (“Survival Rates for Melanoma Skin Cancer”, 2018). However, on the other hand if the melanoma is diagnosed late, and is in its last stage, the survival rate is between 15% and 20% (“Survival Rates for Melanoma Skin Cancer”, 2018). However, each patient’s situation is different, and many factors may affect the survival rate such as the type of melanoma, as well as the tumor thickness.

Symptoms

There are several symptoms that patients with melanoma may experience. These abnormalities include: non-healing sores, pigment in the form of redness or swelling that radiates from the original spot, itching, pain or tenderness, novel changes to an existing mole, and maybe even spots in the iris or blurring of vision (Swetter, 2018).

Etiology

Predisposition

Specific melanoma-related genes can be inherited. Most inherited melanomas often have changes in tumour suppressor genes. The major susceptibility gene is CDKN2A, which encode the P16 and p14ARF proteins. These proteins affect the p53 and retinoblastoma (Rb) cell cycle genes. CDK4 is another gene that is changed through inherited melanomas, preventing them from carrying out their normal activity of controlling cell growth (Long et al., 2011). However, it is important to note that most of the gene changes causing melanoma are not a result of inheritance. They are more likely caused by damage induced by environmental factors (“What Causes Melanoma Skin Cancer?,” n.d.).

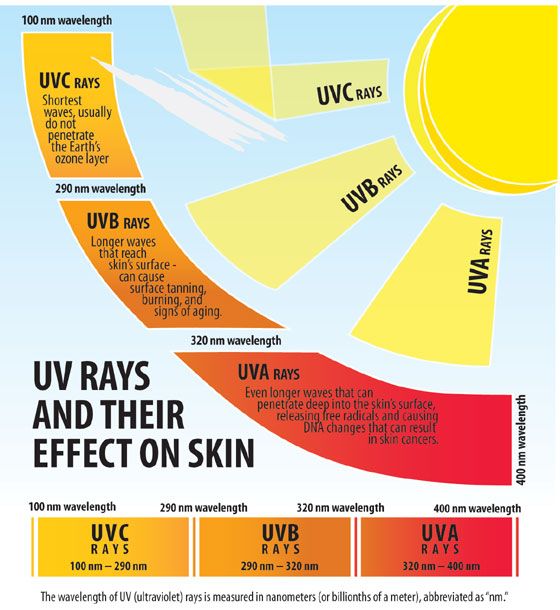

Environmental Factors

Exactly what induces damage in skin cell DNA and how this causes melanoma is not fully understood. It is likely that a combination of factors cause DNA changes. The most known factors are excessive exposure to solar and artificial UV radiation from the sun and tanning beds, respectively. UV ray damage on the DNA in skin cells affects various genes that control how skin cells grow and divide. If such genes stop working effectively, the affected cells become cancerous (“What Causes Melanoma Skin Cancer?,” n.d.). A history of sunburns and intermittent high-intensity sun exposure are more strongly associated with melanoma development compared to cumulative chronic sun exposure (Long et al., 2011).

Risk Factors

Skin Colour

Skin colour plays a protective role of melanoma against UV light. Melanoma is much more common in Caucasian with light skin compared to Blacks with darker skin. Sun-sensitive skin such as fair skin types are more prone to sunburn. Darker skin has been found to protect against melanoma. In fact, in the United States, Caucasians are 8-19 times more likely than blacks to develop melanoma (Koh, Sinks, Geller, Miller, & Lew, 1993).

Figure 1. The graph is of melanoma incidence rates based on race/ethnicity in the United States from 1999-2013

Figure 1. The graph is of melanoma incidence rates based on race/ethnicity in the United States from 1999-2013

Age

It has also been observed that melanoma risk increases by age. The increased risk has been attributed to greater cumulative exposure to environmental agents and UV light (Koh et al., 1993).

Geographic Location

Individuals living closer to the earth’s equator tend to be more susceptible to melanoma. The sun’s rays are more direct to this location resulting in this population experiencing higher amounts of UV radiation compared to those living in higher latitudes. In the same way, those living at higher elevation tend to be exposed to more UV radiation resulting in higher risk (“What Causes Melanoma Skin Cancer?,” n.d.).

Screening for Melanoma

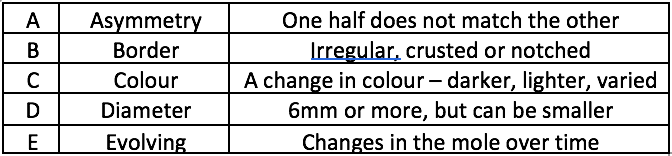

ABCDE Check

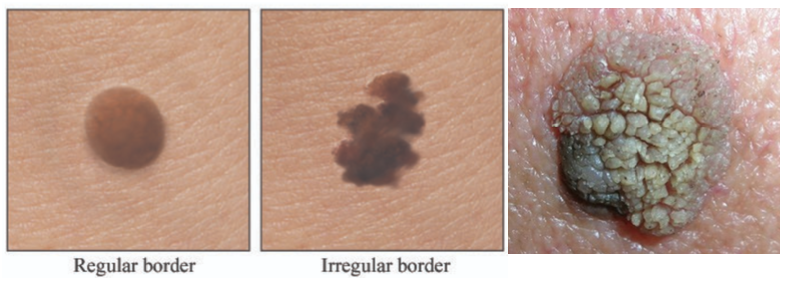

An ABCDE is a quick check that can be performed either by a doctor or a person themselves to help identify if a melanoma is developing (BAPRAS, 2015). This check should be performed if someone is suspicious of a mole or lesion on their body. Dermatologists offer a yearly skin exam where they check a patient's body for any suspicious moles or lesions and can help to diagnose melanoma at an early stage so that there is a higher chance of it being cured. It is recommended that you seek advice from a dermatologist if you suspect that you are developing melanoma because they can confirm it for sure (BAPRAS, 2015). The table shown above states the criteria for each letter check that can be used to determine whether a specific mole or lesion may be cancerous.

The picture on the left above shows the difference between a normal and irregular border. An irregular border is indicative of melanoma because cancerous cells divide in irregular patterns. The picture on the right shows a crusty mole which is also indicative of melanoma as per the criteria on the ABCDE check.

Abnormal Nail (Subungual Melanoma)

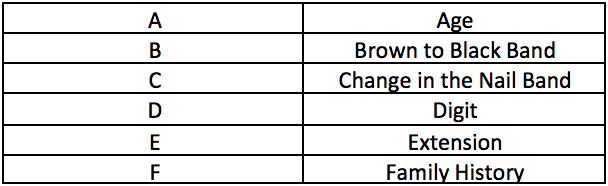

Brown colouration under a nail or at the base of a nail may represent a subungual melanoma (BAPRAS, 2015). Subungual melanoma is a rare type of melanoma that does not have many early diagnostic tools (Levit et al., 2000). One diagnostic tool that was created for early detection of subungual melanoma is called ABCDEF where each letter stands for something similar to the ABCDE check designed for melanoma in general (Levit et al., 2000).

Any noticeable change in a nail should make someone suspicious of developing subungual melanoma. As shown in the table above, age is one factor that should be taken into consideration when checking for subungual melanoma. Any change in the nail band length or colour and as well as family history should also be checked for. Although this check is useful for detecting subungual melanoma early, absolute diagnosis can only be determined through a biopsy (Levit et al., 2000).

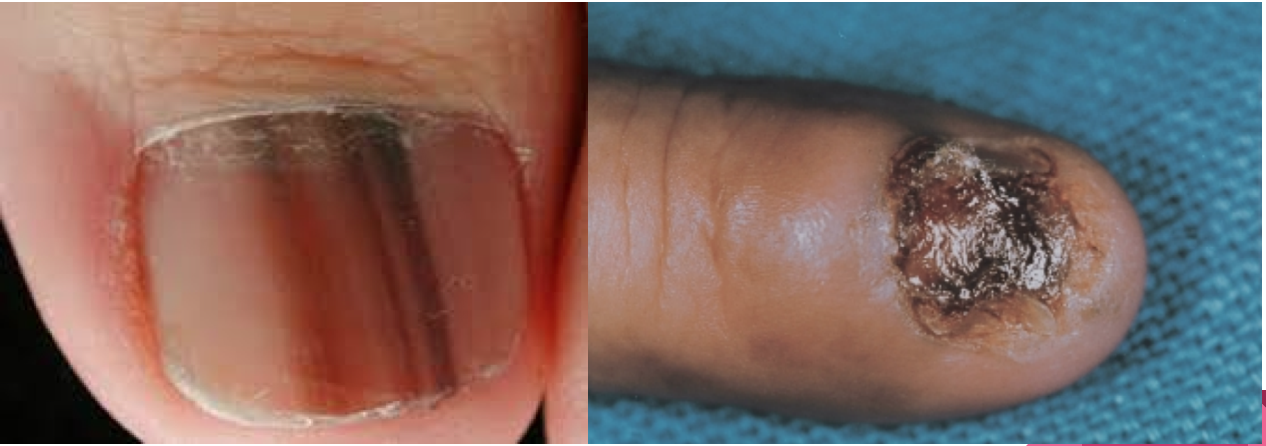

The images shown above are nails of people who have subungual melanoma. The image on the left is of a person's nail who has subungual melanoma at a fairly early stage. The brown and black bands across the nails according to the ABCDEF check indicate that this person is developing subungual melanoma. The image on the right is of a 68 year old female's nail who has had subungual melanoma for 2 years. At this point, the melanoma has spread and completely destroyed the nail.

Excision Biopsy

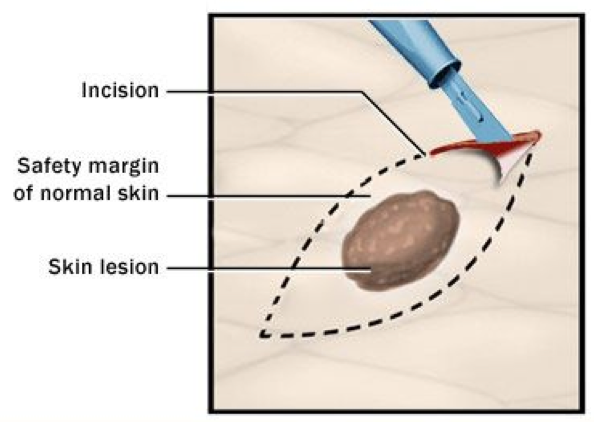

Excision biopsy is another procedure that can be performed to detect for melanoma. This biopsy involves the removal of a mole along with about 2mm of normal skin (BAPRAS, 2015). The extra normal skin is necessary to see if the melanoma is spreading beyond the mole.

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SNLB)

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy (SNLB) is another procedure that is performed on a patient with melanoma to detect whether the melanoma cells have travelled to the lymph nodes in the armpits, neck, or groin region (BAPRAS, 2015). Lymph nodes are small bean shaped tissue that are important for developing an immune response as they contain multiple different types of white blood cells. This is a procedure that is usually conducted prior to any surgery so that affected lymph node areas can also be removed at the same time (BAPRAS, 2015).

Other Screening Procedures:

CT Scans are requested if there is a risk that melanoma may have spread to other parts of the body (BAPRAS, 2015).

Blood tests are also requested to examine whether the liver is functioning normally (BAPRAS, 2015). The reason for why liver function is tested is because the liver regulates the breakdown of old and damaged blood cells.

Fine Needle Aspiration involves inserting a thin needle into the lesion area and collecting a sample of skin cells (Melanoma Research Foundation, 2018). These cells are transported onto a glass slide and sent to the lab for further analysis.

Punch Biopsy involves taking a small piece of skin in the shape of a circle (Melanoma Research Foundation, 2018). This procedure is fairly easy to do and involves administrating patients with local anesthesia meaning that the affected area is numbed.

Pathophysiology

Mutations that occur in the DNA greatly alter cellular functions. Specifically, the cellular rates of proliferation and differentiation become uncontrolled and increased. The mutations to DNA also cause the cell to often ignore apoptosis or rather programmed cell death. They also make the skin and cells more susceptible to the harmful and cancer-causing potential of UV radiation (Swetter, 2018). Interestingly, higher number of birth marks or spots (nevus counts) on the body are a predisposing factor for the disease (Swetter, 2018). This is however a strong correlation and causation has not been established.

The specific mutations are frequently in the BRAF, NRAS and KIT oncogenes. Mutations in oncogenes increase the risk of cancer and these three in particular have been linked with melanoma. Sun exposed areas usually have mutations in the BRAF oncogene whereas areas which aren’t exposed to the sun as much show mutations in the KIT oncogene (Takata, 2010). Some other mutations have also been discovered which lead to disruptions to the p16/Rb pathway, cyclin D1 (CCND1) and cyclin dependent kinase 4 (CDK4) which all alter cell cycle progression and cellular senescence (Sauter, 2002; Takata 2010). Proliferation and telomerase mutations also play a role in speeding up the progression of melanoma (Murata, 2007).

Stages of Skin Cancer

Stage 0 - at this stage melanoma is in situ, meaning that the melanoma cells are only found in the outer layer of the epidermis. In this stage, it is unlikely for melanoma to spread to other parts of the body.

Stage I - This is the primary melanoma stage, where melanoma cells are only found in the skin. - Stage IB - subgroup of stage I, depending on the thickness of melanoma and whether or not the pathologist is able to see ulceration under a microscope.

Stage II - Melanoma is thicker than in stage I, and extends through the epidermis into the dermis (the inner layer of the skin). In this stage, there is a higher chance of spreading. The stage can be divided into 3 subgroups – A, B, or C– depending on the thickness of melanoma and whether there is ulceration.

Stage III - In this stage, melanoma has spread locally or through the lymphatic system, which is a part of the immune system and drains fluid from the body through tubes or vessels. This stage is also divided into subgroups – A,B,C or D – depending on size and number of lymph nodes impacted by melanoma, whether primary tumour has satellite lesion and if ulceration appears under a microscope or not.

Stage IV - Melanoma has spread through the bloodstream to other parts of the body (distant locations on the skin, distant lymph nodes or other organs).

- M1a: the cancer only spread to distant skin.

- M1b: the cancer spread to the lung.

- M1c: the cancer spread to any other location that does not involve central nervous system.

- M1d: The cancer has spread to the central nervous system (brain, spinal cord or cerebrospinal fluid).

Current Treatments, Future Treatments and Implications

Chemotherapy

Vindesine - The vinca alkaloid vindesine has also been evaluated in the adjuvant treatment of malignant melanoma. In a non-randomised trial, researchers have found a highly significant improvement in disease-free as well as the overall survival in patients treated with vindesine following resection of regional lymph nodes compared with patients followed by observation alone.

Levamisole - This is another type of chemotherapy that has been evaluated as an adjuvant treatment following excision of a primary melanoma. In a trial conducted by the National Cancer Institute of Canada, were able to demonstrate a reduction of 29% in both the death rate (p = 0.08) and the recurrence rate (p = 0.09) in a cohort of patients who were randomized to receive adjuvant levamisole as opposed to observation alone.

Gene Therapy

Constitutive activation of certain signal transducer and activator of transcription proteins, including Stat3, has been found in increasing numbers of human cancers. Researchers have found that the levels of activated Stat3 in the B16 tumour cell line are relatively low. Over-expression of a Stat3 Dominant-negative Protein, Stat3b, Induces Cell Death in B16 Tumour Cells in Vitro (Niu et al., 1999).

References

British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons. (2015). Malignant Melanoma. Retrieved November 27, 2018, from http://www.bapras.org.uk/public/patient-information/surgery-guides/skin-cancer/malignant-melanoma

Cutaneous Melanoma. (2018, October 31). Retrieved from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100753-overview

Karimkhani, C. Green, A.C. Nijsten, T. Weinstock, M.A. Dellavalle, R.P. Naghavi. Fitzmaurice, C. (2015). The global burden of melanoma: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Br J Dermatol. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5575560/pdf/BJD-177-134.pdf

Koh, H. K., Sinks, T. H., Geller, A. C., Miller, D. R., & Lew, R. A. (1993). Etiology of melanoma. In L. Nathanson (Ed.), Current Research and Clinical Management of Melanoma (pp. 1–28). Boston, MA: Springer US. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-3080-0_1

Levit, E. K., Kagen, M. H., Scher, R. K., Grossman, M., & Altman, E. (2000). The ABC rule for clinical detection of subungual melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 42(2), 269-274.

Long, G. V., Menzies, A. M., Nagrial, A. M., Haydu, L. E., Hamilton, A. L., Mann, G. J., … Kefford, R. F. (2011). Prognostic and Clinicopathologic Associations of Oncogenic in Metastatic Melanoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29, 1239–1246. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2010.32.4327

Melanoma. (n.d.). Canadian Dermatology Association. Retrieved from https://dermatology.ca/public-patients/skin/melanoma/

Melanoma Research Foundation. (2017, June 26). Diagnosing Melanoma. Retrieved November 27, 2018, from https://www.melanoma.org/understand-melanoma/diagnosing-melanoma

Metastatic Melanoma. (2018). Melanoma Research Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.melanoma.org/understand-melanoma/what-is-melanoma/metastatic-melanoma

Murata, H., Ashida, A., Takata, M., Yamaura, M., Bastian, B. C., & Saida, T. (2007). Establishment of a novel melanoma cell line SMYM‐PRGP showing cytogenetic and biological characteristics of the radial growth phase of acral melanomas. Cancer science, 98(7), 958-963.

Sauter, E. R., Yeo, U. C., von Stemm, A., Zhu, W., Litwin, S., Tichansky, D. S., … & Bastian, B. C. (2002). Cyclin D1 is a candidate oncogene in cutaneous melanoma. Cancer research, 62(11), 3200-3206.

Skin Cancer, Melanoma. (n.d.). Health Link BC. Retrieved from https://www.healthlinkbc.ca/health-topics/hw206547

Skin Cancer Statistics. (2017). Canadian Cancer Society's Advisory Committee on Cancer Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/skin-melanoma/statistics/?region=on

Survival Rates for Melanoma Skin Cancer. (2018). American Cancer Society. Retrieved from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates-for-melanoma-skin-cancer-by-stage.html

Swetter, S. M. (2018, October 31). Cutaneous Melanoma. Retrieved from https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1100753-overview#a5

Takata, M., Murata, H., & Saida, T. (2010). Molecular pathogenesis of malignant melanoma: a different perspective from the studies of melanocytic nevus and acral melanoma. Pigment cell & melanoma research, 23(1), 64-71.

What Causes Melanoma Skin Cancer? (n.d.). Retrieved November 21, 2018, from https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/what-causes.html

What is melanoma skin cancer? (2018). Canadian Cancer Society. Retrieved from http://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/skin-melanoma/melanoma/?region=on

Why melanoma skin cancer is increasing and what we can do. (2017). SkinVision. Retrieved from https://www.skinvision.com/articles/why-melanoma-skin-cancer-is-increasing-and-what-we-can-do

World Health Organization (WHO). (2018). Skin cancers. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/uv/faq/skincancer/en/index1.html

Worldwide Cancer Data. (2018). World Cancer Research Fund. Retrieved from https://www.wcrf.org/dietandcancer/cancer-trends/worldwide-cancer-data