This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Crying

Presentation Slides

What is Crying?

Crying is defined as the shedding of tears in response to an emotional state or physical irritation of the eye (Gracanin, Bylsma & Vingerhoets, 2014). Crying has been defined as a complex secremotor phenomenon that is characterized by the shedding of tears from the lacrimal apparatus, without any irritation of the ocular structures (Newman, 2007). It is often accompanied by alterations in the muscles that regulate facial expression and vocalization (Gracanin, Bylsma & Vingerhoets, 2014). For crying to be described as sobbing, it needs to be accompanied by a set of other symptoms such as: slow but erratic inhalation, occasional instances of breath holding and spasms of the respiratory and truncal muscle groups (Gracanin, Bylsma & Vingerhoets, 2014).

Functions of Crying

Crying can be elicited by various events that range from extremely negative to extremely positive experiences (Gracanin, Bylsma & Vingerhoets, 2014). Crying often occurs in situations that are characterized by separation, loss and helplessness and being overwhelmed by strong emotions. Crying serves two broad functions: intra-individual functions and inter-individual functions. Intra-individual functions of crying refer to the effects that crying has for the individual. These functions are predominantly linked to stress reduction and the experience of mood enhancement and relief that follows crying. Conversely, inter-individual functions of crying involve the effects that crying has on other people. Theories that analyze the social effects of crying stress the signal value of distress vocalizations and/or of human tears. From the attachment theory perspective, crying is viewed as an appeal for the presence and attention of the caregiver. Crying, particularly visible tears, has been shown to promote empathy and prosocial behaviour, facilitates social bonding and reduces inter-personal aggression. Recent research has shown that visible tears impact the evaluation of a human face and identify the need for support. On the other hand, the sound of infants crying has been shown to elicit anger, irritation, frustration and even aggression from others (Gracanin, Bylsma & Vingerhoets, 2014).

Non-Humans Animals and Crying

Humans have been identified as the only species to produce emotional tears. In all mammals and most birds, offspring react with separation calls or distress calls upon being removed from their parents (Gracanin, Bylsma & Vingerhoets, 2014). This is the phylogenetic basis of acoustical crying of human infants. This form of crying is meant to alleviate separation from the parents. In animals, distress calls are mainly displayed by young offspring and they are never accompanied by the production of tears. They are able to produce tears in response to irritation of the eye, or to keep the eyes moist, however, they do not cry in response to a psychological event (Gracanin, Bylsma & Vingerhoets, 2014).

Distress Calls in Mammals

It has been shown that mammals respond to the distress calls of infants, regardless of species (Lingle & Riede, 2014). Researchers wanted to test the theory that a mammal mother’s instinct can recognise calls of any infant, regardless of species. They recorded the cries of various infant mammals. This included humans, fur seals, cats, dogs, young yellow-bellied marmots, sea lions, domestic cats, silver-haired bats and several other deer species. These recordings were played using hidden speakers to wild female mule and white-tailed deers in Canada. The calls were played at both normal and pitched frequencies and a positive response was recorded of the deer approached the speaker, which is similar to how they would react if their own fawn was crying. In experiments, wild mule and white-tailed deers responded equally to the cries of their own fawns as well as those of humans, cats and even infant silver-haired bats. However, they did not approach the speaker when the pitch fell outside the range of her fawn’s call. The researchers wanted to understand if the deers were simply responding to pitch rather than the type of call, so they played generic noises at frequencies outside the range of their fawn’s call. In all instances, the female deer did not respond to the control sounds, indicating that they were able to distinguish between the two types of noises. The results of this experiment suggest that the acoustic traits of infant distress vocalizations are essential for a response by caregivers and the caregivers sensitivity to those acoustic traits may be shared across diverse mammals. Furthermore, the frequency of distress calls across mammals likely differs to make it easier for species to identify each other (Lingle & Riede, 2014).

Mechanism of Crying

The mechanism of crying is attributable to a neuronal connection between the lacrimal gland and the regions of the human brain that regulate emotion (Botelho, 1964). Human tears are synthesized by a concerted arrangement of structures, collectively referred to as the lacrimal system. This response is modulated by various neural circuits in the brain (Botelho, 1964).

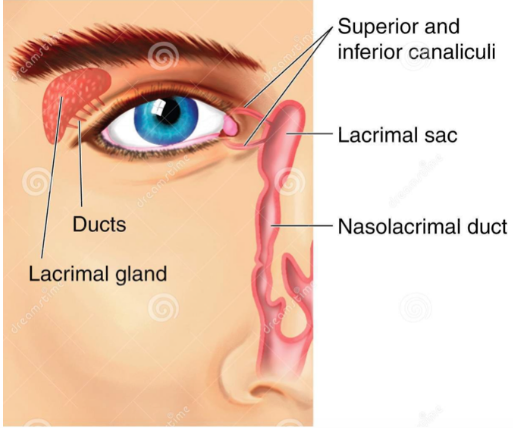

Lacrimal System

The lacrimal system is named after its largest and main gland, called the lacrimal gland, which is responsible for expelling tears through a multitude of ducts around the eye (Botelho, 1964). The lacrimal gland is also commonly referred to as the tear duct. This system is composed of both a secretory and an excretory system, which produces tears and drains the tears, respectively. Tears are produced by the lacrimal gland, which are then secreted through ducts onto the surface of the eye. Some of the liquid evaporates between blinks, and some is drained through the lacrimal punctum, which will eventually pass through the nose. Any excess fluid that was not subject to evaporation or drainage through the punctum will fall over the eyelid, which in turn presents as the tears that an individual cries (Lutz, 1999). The lacrimal system does not solely synthesize and secrete tears, but also collects them (Botelho, 1964). As an individual blinks, the eyelids direct tear fluid towards the punctum. The punctum then acts as a passageway for the tears to move into the lacrimal sac, and subsequently downwards into the nasolacrimal duct (Botelho, 1964). This can explain why when a person is crying, they may also experience a runny nose.

Types of Tears

There are three types of tears: basal tears, reflexive tears, and psychic tears (Lutz, 1999). Basal tears are synthesized at a rate of one to two microliters per minute. Their role is to keep the eye lubricated and regulate any abnormalities on the corneal surface (Lutz, 1999). The production of basal tears maintains a liquid film on the surface of the eye (Botelho, 1964). Reflexive tears are synthesized in response to irritants that come in contact or are around the eye, such physically getting poked in the eye or while chopping onions (Lutz, 1999). They are produced by the excitation of sensory receptors that are positioned in the conjunctiva of the eye and mucous membranes of the nose (Botelho, 1964). Psychic, or emotional, tears are produced by the lacrimal system and are the tears excreted during periods of intense emotion (Lutz, 1999). The lacrimal gland is fundamentally in charge of making reflexive and emotional tears. Interestingly, in a study conducted by Saree Penbharkkul and Samuel Karelitz, it was exhibited that the lacrimal system is not fully developed when a human is born (Botelho, 1964). Only approximately 13% of infants are able to produce tears when crying in the first five days of life. They suggested that this delayed capacity for tear production may be attributed to the impartial development of the parts of the central nervous system that innervate the lacrimal system in newborns (Botelho, 1964).

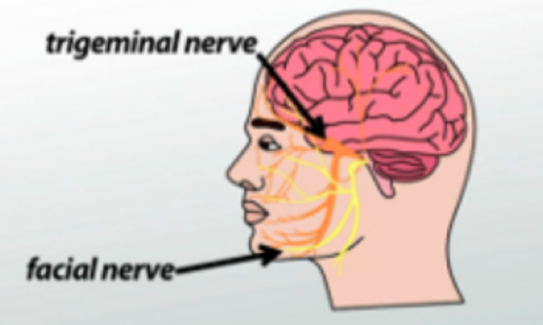

Neurological System

The trigeminal nerve, also known as the fifth cranial nerve, contains the sensory pathway that is responsible for tears (‘Tears’, 2018). The motor pathway is involuntary, and considered to be a part of the autonomic nervous system. This utilizes the pathway of the facial, or seventh cranial nerve (‘Tears’, 2018). Lacrimal gland secretion of proteins, electrolytes, and water is controlled by the activation of sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves that release neurotransmitters (Dartt, 2009). The key neurotransmitters in crying are norepinephrine and neuropeptide Y, which are sympathetic, and acetylcholine and vasoactive intestinal peptide, which are parasympathetic. All of these neurotransmitters stimulate separate signalling pathways, however these pathways do interact. Lastly, enkephalins, which are related to endorphins, activate an inhibitory pathway that blocks lacrimal gland secretion and crying (Dartt, 2009).

Humans and Crying

The Amygdala

Everyone cries, it is one of the first behaviours we express as infants (Oaklander, 2016). There are times in everyone’s life where we have experienced times when we cry out of both frustration or pure joy (Oaklander, 2016). An example is if you were just accepted into medical school, a dream that you worked towards throughout your academic career or the loss of a family member. A question everyone has thought to themselves: is there a difference between the tears of joy or sadness?

The amygdala is a structure within the brain that registers emotional reactions that in turn send its signals towards the hypothalamus (Lewis, 2016). The hypothalamus in turn activates the autonomic nervous system which proceeds to tear production (Lewis, 2016). The hypothalamus cannot tell what type of response is occurring, whether we are sad, happy, stressed, angry (Lewis, 2016) Basically, its role is to release the buildup of emotions that is occurring and it cannot distinguish between different types of emotions (Lewis, 2016).

Why Do We Cry When We Are Happy?

It is an interesting concept to have negative emotion occur while you are happy. A group of researchers in Yale have figured out why exactly we cry tears of joy. Aragón et al., 2015 explained their results from their experiment in terms of a equilibrium of emotions. Individuals who participated in the study were presented with extremely positive emotions and their baseline emotional levels were recorded (Aragón et al., 2015). They wanted to see if there was a difference with the time it would take for individuals to return to this baseline emotional level and whether they used dimorphous expressions. The researchers found that individuals who responded to these extremely positive events with both a positive and negative emotion (crying) returned to their baseline emotional level quicker than participants who did not (Aragón et al., 2015). The researchers believe by responding to an overwhelmingly positive emotion with a negative one allows the individual to recover from strong emotions. Examples of this could be screaming while winning the lottery or crying at your child’s graduation (Aragón et al., 2015).

Tear Composition

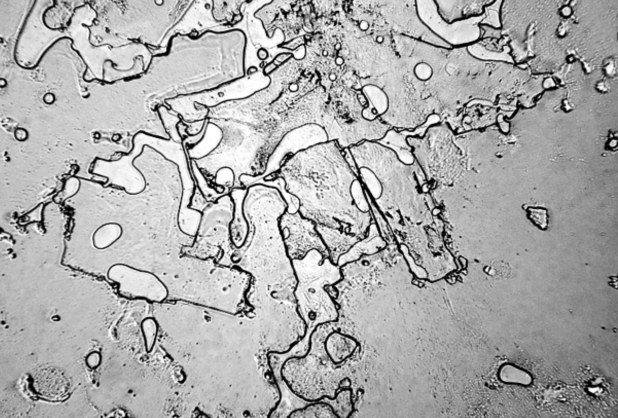

Your body produces 3 types of tears as stated above. The basal variety is used as a lubricant and protectant of the eye and coat your eyes each time you blink (Botelho, 1964). There are also reflex tears which are another form of protection released in response to wind, dirt etc… Finally, there are emotional tears (Botelho, 1964). Each of these types of tears is a combination of salt water, oils, antibodies and enzymes (Botelho, 1964). In the project topography of tears the photographer, Rose-Lynn Fisher examined dried human tears under a microscope to create a collection of different images. Her main conclusion was that tears coming from love developed patterns of complex beauty whereas tears coming from negative emotions became disordered (Fisher, 2017).

Hormones and Tears

Emotional tears have a much different make-up than basal and reflex tears. There is a much higher concentration of hormones such as adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), which humans produce under stress and prolactin, which controls the neurotransmitter receptors in the lacrimal glands that release tears (Walter, 2006). This may also explain why women cry more often as they have higher levels of prolactin in their bodies, especially after puberty (Walter, 2006). It is speculated that emotional crying may be the body’s way of flushing out the increased concentration in hormones present in the body when experiencing strong feelings (Walter, 2006). However, this seems unlikely since the lacrimal gland itself is small and cannot flush out enough hormones to provide relief to the body (Walter, 2006).

Sex Hormones and the Lacrimal Glands

The structure and function of the lacrimal gland is partly mediated by the regulation of sex hormones such as androgens (Truong et al., 2014). Reduced androgen activity has been shown to result in inflammatory changes in the lacrimal gland such as aqueous-deficient dry eye (Truong et al., 2014). Women with low serum levels of androgens have been shown to exhibit dry eye syndrome (Truong et al., 2014). Furthermore, women that are in menopause or have undergone ovariectomy exhibit a lacrimal gland deficiency, therefore not producing the fluid that contributes to the aqueous layer of the tear film (Truong et al., 2014). In contrast, men who take anti-androgen medication have not shown a decrease in their tear reduction, suggesting that there may be sex-related differences in the effect of androgens on the lacrimal gland (Truong et al., 2014).

Likewise, animal studies have shown significant sex-related differences in the lacrimal gland of various species. For instance, male rabbits have larger lacrimal glands and have a greater number of cells than their female counterparts (Truong et al., 2014). In rats, a reduction in androgens due to castration of the males resulted in resemblance of the lacrimal gland to female rats (Truong et al., 2014). On the other hand, female and castrated rats that were treated with testosterone lead to the lacrimal glands resembling that of male rats (Truong et al., 2014). Androgen activity or change in the size of the gland has not been shown to be proportional to the secretory capacity of the lacrimal tissue (Truong et al., 2014). Castrated male rats showed an increase in tear volume while female rats that underwent ovariectomy showed no significant difference in tear volume (Truong et al., 2014). Interestingly, administration of androgens restored lacrimal tissue regression, but decreased its secretion capacity (Truong et al., 2014).

It is speculated that sex-related differences in the lacrimal gland are due to changes in gene expression . The lacrimal gland expresses genes for androgen receptors (Truong et al., 2014). The density of these receptors is much greater in male rats than females, however when both sexes undergo either orchiectomy (castration) or ovariectomy, the number of androgen receptor proteins is identical (Truong et al., 2014). It was observed that administration of testosterone to castrated male rats restored the density of androgen receptors in the lacrimal gland (Truong et al., 2014).

Psychopaths and Crying

Psychopaths make up approximately 1% of the population (Hare, 2003). They are individuals who unlike the rest of us act slightly differently and react to social situations in a unique way. Psychopaths are generally seen as individuals who do not have emotions, but rather are able to mimic the emotional response of others without truly feeling anything. The Hare checklist is used to diagnose an individual as a psychopath. Each person is given a rating of 0-2 for 20 items by a psychiatrist based on the degree to which they exhibit that behaviour (Hare, 2003). A few notable qualities are cunning and manipulative, glib and superficial charm, and criminal versatility. A study done by Rice et. al in 1992 looked at the likelihood of first time offenders to reoffend after being released from prison, based off of whether or not they were treated with empathy training. The participants were also rated on the Hare checklist and given a diagnosis of psychopathic or not. The results they found were quite disturbing—that is, individuals who were treated with empathy training who were not psychopaths showed a much lower number of re-offenses. On the contrary, individuals who were psychopaths who were treated with empathy training actually had a higher rate of re-offences. This suggests that psychopaths are able to learn from their environment and use emotions to manipulate the general population.

So can psychopaths cry? The answer is one we do not have a clear cut answer to, as we do not fully understand the complete mechanism of emotional tears or the wiring of a psychopaths brain. Dr. David P. Bernstein from the forensic psychiatric center de Rooyse Wissel seems to think that indeed they can, as he hypothesizes that psychopathy is on a spectrum, and therefore certain individuals are more prone to emotional vulnerability then others. This is why he believes that certain psychopaths could show some weakness and cry. The problem is, we still do not know if this weakness is a learned reaction from their environment like the Rice et al. study may suggest, or rather a genuine human emotion. More work is needed to be done to fully understand this highly complex topic.

References

Aragón, O. R., Clark, M. S., Dyer, R. L., & Bargh, J. A. (2015). Dimorphous Expressions of Positive Emotion: Displays of Both Care and Aggression in Response to Cute Stimuli. Psychological Science, 26(3), 259–273. http://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614561044

Bernstein, D. P. (2012). “ Big Boys Don’t Cry!” Or Do They?: Can Forensic Patients Change?.

Botelho, S. (1964). Tears and the Lacrimal Gland. Scientific American, 211(4), 78-87. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/24931663

Dartt, D. A. (2009). Neural Regulation of Lacrimal Gland Secretory Processes: Relevance in Dry Eye Diseases. Progress in Retinaland Eye Research, 28(3), 155–177. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2009.04.003

Fisher, R. L. (2017). The Topography Of Tears. Retrieved from http://rose-lynnfisher.com/books.html

Gračanin, A., Bylsma, L. M., & Vingerhoets, A. J. (2014). Is crying a self-soothing behavior?. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 502.

Hare, R. D. (2003). The psychopathy checklist–Revised. Toronto, ON.

Lewis, J,G. 2016. Why Do We Cry When We’re Happy? Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/brain-babble/201308/why-do-we-cry-when-were-happy

Lingle, S., & Riede, T. (2014). Deer mothers are sensitive to infant distress vocalizations of diverse mammalian species. The American Naturalist, 184(4), 510-522.

Lutz, Tom (1999). Crying : the natural and cultural history of tears (1. ed.). New York: W. W. Norton.

Newman, J. D. (2007). Neural circuits underlying crying and cry responding in mammals. Behavioural brain research, 182(2), 155-165. Oaklander, M. 2016. The Science of Crying. Time. Retrieved from http://time.com/4254089/science-crying/

Rice, M. E., Harris, G. T., & Cormier, C. A. (1992). An evaluation of a maximum security therapeutic community for psychopaths and other mentally disordered offenders. Law and human behavior, 16(4), 399.

Tears. (2018, March 02). Retrieved March 13, 2018, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tears#cite_note-ReferenceA-3

Truong, S., Cole, N., Stapleton, F., & Golebiowski, B. (2014). Sex hormones and the dry eye. Clinical and Experimental Optometry, 97(4), 324-336.

Walter, C. (2006). Why do we cry?. Scientific American Mind, 17(6), 44-51.