This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Introduction

Hiccups, also known as hiccoughs and singultus, is a condition that has been experienced by most individuals within their lifetime. Hiccups are due to the involuntary contraction of the diaphragm, which may be due to many factors. Additionally, it can be influenced by peripheral nerve damage and irritation, central nervous system disorders, and metabolic disorders. Hiccups are usually temporary and very little research is known about lengthened and uncontrollable hiccups. Moreover, there are many myths regarding treatments for hiccups which can or cannot be supported by scientific evidence. There are also medications that can be used to treat intractable hiccups; however, there is minimal research due to small sample sizes. In this presentation, we will go over a case study describing the symptoms and treatments on an individual with continuous hiccups.

Pathophysiology

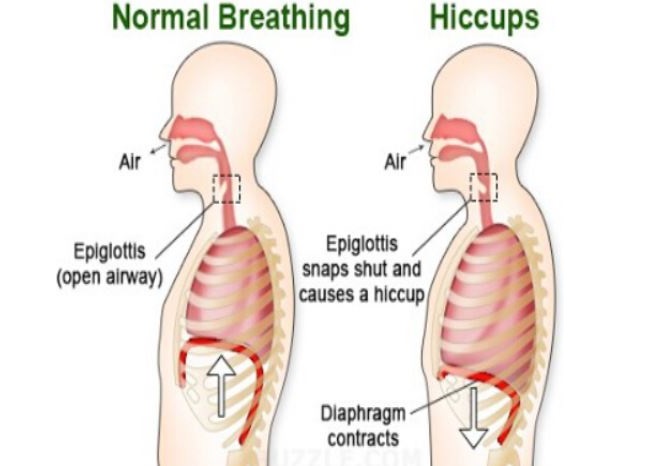

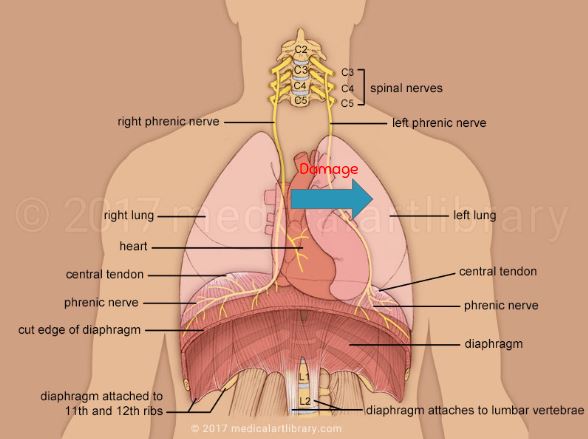

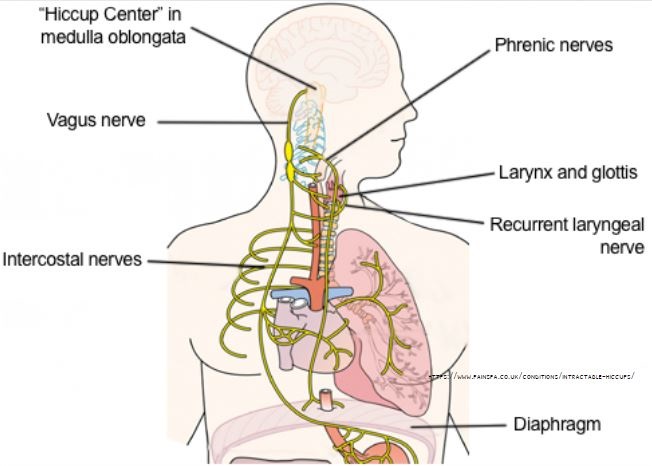

The general pathophysiology of hiccups begins as an afferent signal from diaphragm sides, distal esophagus or stomach which use the phrenic nerve, vagus nerve and sympathetic chain located from T6-T12 (Howes, 2012) to travel to the central location of the hiccup reflex. These afferent signals travel to the medulla where the hiccup reflex is initiated and the signal is processed. The reflex arc uses the efferent nerves to transmit the processed response signal to the diaphragm (Howes, 2012). The transmission of the response signal causes involuntary and spasmodic contraction of the diaphragm, more specifically the left hemidiaphragm (Howes, 2012). The contraction allows for sudden inspiration which is blocked by the involuntary closure of the glottis (Lembo, 2018). This involuntary process produces the “hic” sound the is heard during hiccups (Mayo Clinic, 2017; Lembo, 2018). Once the contractions begin hiccups occur at a rate of four to sixty hiccups per minute depending on the individual and cause. (Howes, 2012).

There are many causes associated with this involuntary process. The severity of hiccups can be indicated by the duration of the hiccups. Hiccups lasting less than 48 hours can be caused by excessive alcohol, carbonated beverages, overeating, emotional stress, sudden excitement, aerophagia, cold showers, drinking cold beverages, drinking hot beverages (Kranke, 2018).

If hiccups last more than 48 hours it is important to contact the doctor as the hiccups could be triggered by the following peripheral nerve damage/irritation, central nervous system disorders, or metabolic disorders (Kranke, 2018).

Peripheral Nerve Damage and Irritation

Hiccups induced from the irritation of the phrenic and diaphragmatic nerves can be caused by a subphrenic abscess, myocardial infarction, esophageal cancer, splenomegaly, hiatus hernia, hepatomegaly, or pericarditis (Kranke, 2018).

Hiccups induced from the irritation of the vagus nerve can be caused by pharyngitis, neck cyst, goiter cyst, asthma, foreign body induced irritation in the tympanic membrane, pneumonia, bronchitis, esophagitis, tuberculosis, lung cancer, bowel obstruction, Crohn disease, hepatitis,, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, gastric cancer, prostatic cancer, pancreatic cancer, appendicitis, abdominal abscess or aortic aneurysm. (Kranke, 2018).

Central Nervous System Disorders

Hiccups induced from CNS may be the result of structural lesions, vascular lesions, infections, epilepsy or trauma (Kranke, 2018).

Structural lesions: multiple sclerosis, cranial neoplasm, ventriculoperitoneal shunt, or Syringomyelia

Vascular lesions: vascular insufficiency, cranial infarction, cranial hemorrhage, or aterio-venous malformation

Infections: Malaria, meningitis, herpes, neurosyphilis, or encephalitis

Metabolic Disorders

Electrolyte imbalances can occur in the body due to metabolic disorders. This causes a direct decrease in the ability to inhibit the activation of the hiccup reflex arc. Some disorders that may cause long term hiccups are diabetes, alcoholism, gout, alkalosis, uremia, hyponatremia or hyperkalemia (Kranke, 2018).

Treatments

Myths

There are many non-pharmacological treatments for hiccups commonly heard such as: holding your breath, breathing into a paper bag, drinking water, biting on a lemon wedge, and being scared. But do any of these really work? Is there any scientific data backing up any of these claims, or are they all just myths?

The mechanism proposed to be behind breath holding, breathing into a paper bag and being scared (and gasping with fright) is that it interrupts or stimulates respiration. Forcible tongue traction, touching the hard and soft palate, gargling, swallowing a lemon wedge with Angostura bitters, swallowing granulated sugar, and drinking water rapidly stimulate the uvula and nasopharynx which is thought to stop hiccups. Counterirritation of the nerves involved in hiccuping or the diaphragm itself are also thought to stop diaphragmatic spasms. Putting pressure on eyeballs and rectal massages are some examples of irritating the vagus nerve, while applying pressure to points of diaphragmatic insertion or chest compression (pulling knees to chest or leaning forward) irritate the diaphragm and stop spasms (Friedman, 1996, Launois et al., 1993, and Chang and Lu, 2012).

Breathing into a bag and breath holding

The mechanism behind this is that hiccups most often begin during inspiration and are inhibited by elevations in PaCO2. Breath holding and breathing into a paper bag are thought to restore normal phrenic nervous rhythms (Ropper & Samuels 2009 and Aldrich & Tso 2005). A study done by Morris et al. (2004) tested breath holding as a means to terminate hiccups in 6 pregnant women. Using the technique of supra-supramaximal inspiration, it was postulated that this technique may terminate spasmodic diaphragm contractions by effectively immobilising the diaphragm for 20 seconds, while also increasing PaCO2. Lung expansion may also cause a reflex reduction in phrenic nerve tonicity (Morris et al. 2004).

Eating a lemon wedge saturated in Angostura bitters

This study included 16 participants, and was only tested on hiccups induced by ethanol (i.e. ingestion of alcohol). A lemon wedge saturated in Angostura bitters was orally administered. There was an 88% success rate (14 out of 16 participants), with the two cases where the treatment failed, the hiccups were overcome after a second treatment. The results confirm “anecdotal success” (Herman & Nolan 1654).

Intranasal vinegar

Success of intranasal vinegar instillation was seen in a patient with tracheostomy related hiccup. Nose drops of small amounts of vinegar was used to stimulate the dorsal pharynx at the supplied area of afferent branches of the hiccup reflex arc and was seen to be effective. Intranasal vinegar might stimulate dorsal wall of nasopharynx where the pharyngeal branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve, which is thought as an afferent of the reflex arch of hiccup, is distributed. This method is a safe and convenient to stimulate the dorsal wall of the nasopharynx (Iwasaki et al. 2007).

The Heimlich maneuver

This study used the Heimlich maneuver, usually utilized to expel aspirated water, vomitus, debris, and other foreign matter to stabilize the diaphragmatic spasms in hiccups. This procedure elevates the diaphragm, increasing intrathoracic pressure and compressing the lungs (Heimlich & Patrick 1988). A modified Heimlich maneuver with 3 thrusts delivered at 10 second intervals was used and seen to be effective in terminating the hiccup immediately. Presumably, this maneuver caused the cessation of the diaphragmatic contractions responsible for the hiccups (Heymann 2003).

Other approaches with rare reports of effectiveness for intractable hiccups include hypnosis, acupuncture, and even surgery. Two examples surgical procedures are a “nerve block” that stops the phrenic nerve (the major nerve supply for the diaphragm) from sending signals so that the diaphragm stops contracting, and implantation of a pacemaker that results in more rhythmic contractions of the diaphragm (The Myth and Mystery of Hiccups. n.d.).

These measures seem to be most effective in transient hiccups and are less effective with persistent hiccups, but it is hard to know if the treatments are really effective or not because they typically resolve themselves, and there is not enough scientific evidence or research yet to back up any of these claims (Schuchmann & Browne 2007). With the research already been conducted on some of these treatments, a lot are anecdotal and have small sample sizes. Overall, these treatments are generally safe to use so it can be worth a try. These remedies may be very convenient and less hazardous, however, their effectiveness to treat serious hiccups are usually uncertain (Chang & Lu 2012).

Some treatments that have less merit, and are more superstitious are curing hiccups with hypnosis and the superstition that hiccups are caused by hate (The Myth and Mystery of Hiccups. (n.d.) and Hindy 2014). An old wives’ tale asserts that you only have hiccups when someone is talking about you in a negative way (in Russia, it’s when someone is thinking about you in a good or bad way) and the only way to cure it is to guess the name of the person who is doing it (Hindy 2014). Of course these aren’t true, but again if you’re desperate it’s worth a try.

Pharmacological Treatments

When it comes to pharmacological treatments, there are not many large randomized control trials nor consensus statements on treating hiccups among researchers. As a result, most of the understanding surrounding treatments for hiccups is from a small number of patients. There are medications used frequently for hiccups that are hard to control and very difficult to treat, otherwise known as intractable hiccups. These treatments include Chlorpromazine, Haloperidol, Metoclopramide, Gabapentin, and Baclofen.

Chlorpromazine

This is the sole medication that is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (Woelk, 2011). Because dopamine is a neurotransmitter known to be a part of the hiccup reflex, Chlorpromazine acts by behaving as a dopamine antagonist in the hypothalamus to reduce the effects of dopamine (Woelk, 2011). As a result, Chlorpromazine is evidently an antipsychotic that affects neural activity – impacting your mood, concentration, etc. (Nausheen, Mohsin, & Lakhan, 2016). However, there are many side effects including hypotension, urinary retention, glaucoma, and delirium (Woelk, 2011). The recommended doses necessary for the drug to work is 25 mg four times a day, or 50 mg four times a day if required (Nausheen, Mohsin, & Lakhan, 2016). Additionally, the method of administration is either intravenously, intramuscularly, or taken orally (Nausheen, Mohsin, & Lakhan, 2016).

Haloperidol

Haloperidol is also shown to be effective in treating hiccups. Similar to Chlorpromazine, researchers assume that it plays a role as a dopamine antagonist (Woelk, 2011).

Metoclopramide

Like chlorpromazine and haloperidol, Metoclopramide is a dopamine agonist; however, it is less effective as a dopamine antagonist (Woelk, 2011).

Gabapentin

This is a drug that is used to decrease pain in individuals with cancer and is also used for neuropathic pain management (Woelk, 2011). The mechanism of Gabapentin in hiccups is not well understood; however researchers believe that it has the ability to block neural calcium channels and promote the release of GABA which modulates the excitability of the diaphragm (Woelk, 2011). There are no major side effects of this drug; however, it can cause temporary sleepiness (Woelk, 2011).

Baclofen

Baclofen is a structure that is similar to GABA and has the ability to reduce excitability and has the effect of preventing the hiccup reflex (Lee et al., 2010). It is expected that baclofen reduces the synaptic transmission at the spinal cord and has the ability to prevent muscle spasms associated with hiccups (Lee et al., 2010). Baclofen is taken orally and is absorbed quickly. It is eliminated from the body in about 3-4 hours by the kidney (Lee et al., 2010). Side effects of Baclofen include confusion, weakness, insomnia, etc. Researchers have also revealed that individuals get involuntary contractions if one stops using the drug. It is recommended that the dosages should be steadily lowered when one stops using this drug (Lee et al., 2010).

Case Study

Case Study: A German Soldier’s Incessant Case of Singultus

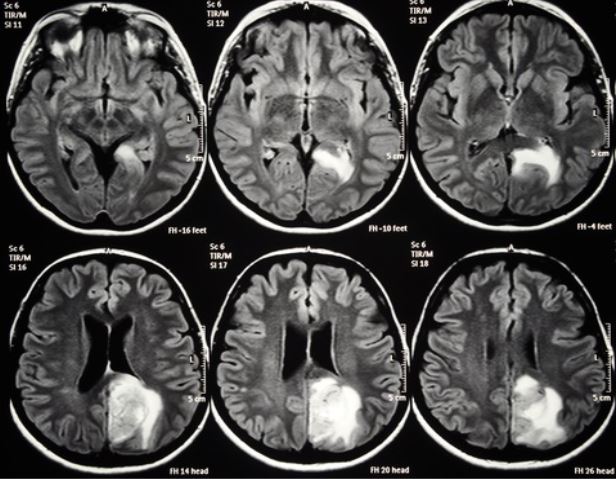

A man in his mid-20s reports that his case of singultus has not recovered, despite his constant personal management of the condition via consuming cold water. An overall exterior bodily examination did not generate any significant discoveries. The patient started using metoclopramide as an initial medication, still resulting in failure for recuperation. Furthermore, tests such as, “gastroscopy, [laboratory testing for stomach-related factors, infection testing], blood count, and abdominal computed tomography (CT)” (Eisenächer et al., 2011) were completed, still presenting no conclusions. Over the progression of the disease, the man recounted periodic episodes of “lack of concentration and dizzy spells” (Eisenächer et al., 2011). As a result, he was not able to complete quotidian tasks, such as driving.

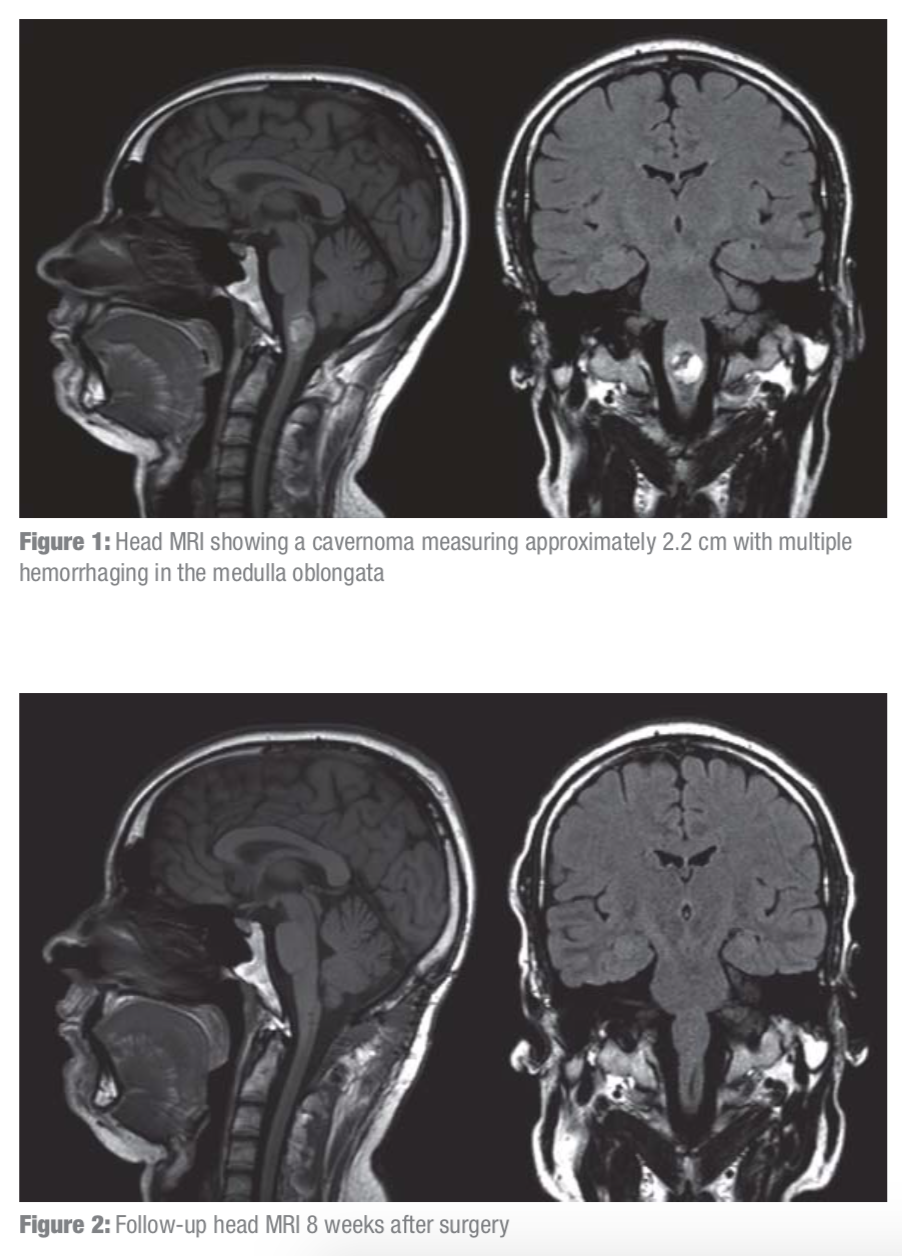

The inconclusive diagnosis resulted in the man being taken to the Berlin Forces’ Hospital, where a more thorough internal examination uncovered “a slight bilateral kinetic tremor…, double vision, and paresthesia in both arms” (Eisenächer et al., 2011). After, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head was taken, ultimately uncovering a “space-occupying lesion measuring 2.2 cm in the medulla oblongata” (Eisenächer et al., 2011). Prior to a formal surgery, the patient suffered an immediate worsening in awareness and breathing. A CT scan revealed “hemorrhaging into the medullary cavernoma” (Eisenächer et al., 2011). All affecting blood vessels and the cavernoma were surgically detached from the brain. This surgery had cured the singultus; however, effects of the surgery include a “slight tingling in the soles of the feet” (Eisenächer et al., 2011) which did not have a significant impact on the patient’s day-to-day routine. Through multiple imaging testing post-surgery for approximately 2 months, it was found that the flesh in the surgically involved area improved and any appearance of growth or bleeding was lacking.

From this case, it is essential to know that if pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions have not succeeded in curing hiccups, the source of the hiccups might result from an exceptional case, which should be examined using additional diagnostic processes.

Presentation Slides

References

Aldrich T. K., Tso R. (2005). The lungs and neuromuscular diseases. Textbook of Respiratory Medicine. 4th ed.Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier Saunders; 2005.)

Chang, F., & Lu, C. (2012). Hiccup: Mystery, Nature and Treatment. Journal of Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 18(2), 123-130. doi:10.5056/jnm.2012.18.2.123

Eisenächer, A., & Spiske, J. (2011). Persistent hiccups (singultus) as the presenting symptom of medullary cavernoma. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 108(48), 822.

Friedman, N. (1996) https://accpjournals-onlinelibrary-wiley-com.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/doi/abs/10.1002/j.1875-9114.1996.tb03023.x

Heimlich H.J., Patrick E.A. (1988). Using the Heimlich maneuver to save near-drowning victims. Postgrad Med, 84, pp. 62-67

Herman JH, Nolan DS. A bitter cure. N Engl J Med 1981;305:1654

Heymann WR. (2003) The Heimlich maneuver for hiccups. J Emerg Med. 2003;25:107–108.

Hindy, J. (2014). 9 Things You Don't Know About Hiccups. Retrieved from https://www.lifehack.org/articles/lifestyle/9-things-you-dont-know-about-hiccups.html

Howes, D. (2012). Hiccups: a new explanation for the mysterious reflex. Bioessays, 34(6), 451-453. Iwasaki N, Kinugasa H, Watanabe A, et al. [Hiccup treated by administration of intranasal vinegar.] No To Hattatsu. 2007;39:202–205. [Japanese]

Kranke, P. (2018, November 30). Hiccups. Retrieved March 2, 2019, from https://online.epocrates.com/diseases/104063/Hiccups/Credits

Launois, S, Bizec JL, Whitelaw WA, Cabane J, Derenne JP. (1993). Hiccup in adults: an overview. European Respiratory Journal 1993 6: 563-575; DOI: https://erj-ersjournals-com.libaccess.lib.mcmaster.ca/content/6/4/563.article-info

Lee, J. H., Kim, T. Y., Lee, H. W., Choi, Y. S., Moon, S. Y., & Cheong, Y. K. (2010). Treatment of Intractable Hiccups With an Oral Agent Monotherapy of Baclofen -A Case Report-. The Korean Journal of Pain,23(1), 42. doi:10.3344/kjp.2010.23.1.42

Lembo, A. J. (2018). Hiccups. UpToDate. Retrieved March 2, 2019, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/hiccups#H37011495 Mayo Clinic. (2017, May 24). Hiccups. Retrieved March 2, 2019, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hiccups/symptoms-causes/syc-20352613 Morris L, Marti J, Ziff D. (2004). Intractable hiccoughs in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2004;24:474.

Nausheen, F., Mohsin, H., & Lakhan, S. E. (2016). Neurotransmitters in hiccups. SpringerPlus,5(1). doi:10.1186/s40064-016-3034-3

Ropper A. H., Samuels M. A. (2009). Disorders of the autonomic nervous system, respiration, and swallowing. Principles of Neurology. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2009.

Schuchmann JA, Browne BA. (2007). Persistent hiccups during rehabilitation hospitalization: three case reports and review of the literature. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2007;86:1013–1018

The Myth and Mystery of Hiccups. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://blog.content.health.harvard.edu/blog/columns/the-myth-and-mystery-of-hiccups/

Woelk, C.J. (2011). Managing Hiccups. Can Fam Physician, 57(6), 672-675.