This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Presentation Slides

Introduction

The most efficient way to target a large audience is through social media. Social media has been used to direct attention towards a wide variety of issues and other serious topics to even simple things like the best restaurants in Toronto. One topic that has received a lot of attention is veganism, evident by the drastic increase in vegan cafés, restaurants, and food products. Veganism is a lifestyle that involves no consumption of animal products, including dairy, meat, fish and others. While the vegan diet has been a concept since even before we were even born, it has been receiving an increasingly amount of attention on media recently (Quinn, 2016). This can be attributable to the global concern over climate change, heart disease and cancer, which are presumed to influenced greatly by meat consumption (Appleby & Key, 2016). Veganism sounds beneficial to both the individual and the environment, but it receives a lot of negative stigmatization. As such, we sought to examine the effects of a vegan diet on key factors like nutritional content, the cardiovascular system, exercise performance, weight loss, environmental effects and long-term effects on the environment and overall human wellbeing.

Nutrition

While animal products are rich in protein, the adequacy of protein from vegan diets has long been a topic of interest. Vegan plant-based diets are associated with a great number of health benefits. In particular, diets high in unrefined plant foods are associated with greater overall health, lifespan, immune function, and cardiovascular health (Fuhrman & Ferreri, 2010). The elimination of meat and increased consumption of plant foods corresponds to greater quantities of nutrients such as fiber, vitamins, minerals and phytochemicals (Fuhrman & Ferreri, 2010).

Protein Requirements

It is essential to note that although protein is an essential nutrient that holds a vital part in the functioning of the body, humans do not require great quantities of it. In North America, 10-12% of vegans’ calories are retrieved from protein while 14-18% of non-vegetarians’ calories come from protein (Mangels, 1999). Thus, it is evident that vegan diets result in lower levels of protein intake. However, it is important to recognize that a higher level of protein intake does not necessarily correspond to a greater level of health. In fact, high protein diets may have negative consequences in regards to risk of osteoporosis and kidney disease (Mangels, 1999). On average, recommended dietary allowance (RDA) recommends that for every pound one weighs, they intake 0.36 grams of protein (Mangels, 1999). In comparison, vegan athletes’ protein requirements can range from 0.36-0.86 grams of protein/pound (Mangels, 1999). This indicates that protein supplements are not required in order to meet these requirements.

Overall Protein Adequacy in Vegan Diets

Oftentimes, an area of concern arises as to how vegans are able to reach an adequate level of protein intake. This concern is invalid and as a matter of fact, vegans rarely have any difficulty reaching their daily protein intake. A vegan diet is able to sufficiently meet human dietary protein requirements, in the case that energy requirements are fulfilled and the individual consumes a variety of foods (Marsh et al., 2012).

It is a common misconception that the only high protein foods are those that are not plant-based, such as eggs, milk, meat and fish. Rather, soybeans, quinoa and spinach are also high protein sources (Mangels, 1999). Notably, green vegetables such as kale and broccoli, have measurable micronutrient contents per kcal and also provide a high level of protein (Fuhrman & Ferreri, 2010). Further, traditional legumes, nuts and seeds are protein-rich foods that sufficiently allow vegan diets to achieve their recommended daily protein requirements (Mariotti & Gardner, 2019). As seen in Table 1, most plant foods contain a sufficient amount of protein. Common respectable food sources including legumes, soy products, nuts and seeds (Marsh et al., 2012). Many grains and vegetables also contain protein, but in lower doses (Marsh et al., 2012)

Table 1: Sample Vegan Menu Indicating the Ease of Protein Requirements

Protein (grams)

Breakfast:

1 cup Oatmeal 6

1 cup Soy Milk 7

1 medium Bagel 10

Lunch:

2 slices Whole Wheat bread 7

1 Cup Vegetarian Baked Beans 12

Dinner:

5 oz firm Tofu 12

1 cup cooked Broccoli 4

1 cup cooked Brown Rice 5

2 tbsp Almonds 4

Snack:

2 tbsp Peanut Butter 8

6 Crackers 2

TOTAL: 77

Protein Recommendation for Male Vegan: 63

Amino Acid Protein Adequacy in Vegan Diets

Humans have a biological requirement for essential amino acids rather than protein (Mangels, 1999). It is a common myth that amino acid intake is inadequate in vegan diets (Mariotti & Gardner, 2019). The idea that majority of plant foods are lacking certain amino acids, is incorrect (Mariotti & Gardner, 2019). A more accurate statement would be that the amino acid distribution profile is more ideal in animal foods in comparison to plant foods (Mariotti & Gardner, 2019). Out of the twenty amino acids, there are nine that humans are unable to make, and as a result these are considered the essential amino acids. These essential amino acids must be acquired from diets, as they are all necessary in order to make protein (Mangels, 1999). These diets contain vegetables, beans, grains, nuts and seeds, which contain a sufficient amount of energy in order to maintain their weight (Mangels, 1999). Most plant-based foods contain the essential amino acids, with a few amino acids being present at low levels (Mangels, 1999). In order to resolve this problem, professionals in the past recommended combining food that is low in one amino acid with one that has high levels of the same amino acid in order to overcome any deficits and achieve favourable amino acid levels (Mangels, 1999).

It is now apparent that protein combining is not necessary, given that energy intake is adequate and the individual consumes a variety of plant foods throughout the day (Marsh et al., 2012). This is partly due to the fact that the human body has indispensable amino acids which are able to complement dietary proteins (Marsh et al., 2012). Lysine deficit may only be an area of concern in vegans who have a low protein intake due to the fact that their protein intake is based on, for example, grains alone (Mariotti & Gardner, 2019). This is highly unrealistic, and as such it is concluded that protein intakes and amino acids are adequate in vegan diets (Mariotti & Gardner, 2019). It is unnecessary to continuously combine various plant proteins during meals, as a wide variety of foods help the human body to maintain a pool of amino acids which consequently allow for an adequate amount of dietary protein (Marsh et al., 2012).

Exercise - Abhay

Change in Exercise Performance

A common conception amongst general society and athletes is that meat is an integral component of diet. While vegetables and fruits are also considered important, they are conceived to be poor sources of protein. This is understandable as animal-based protein does indeed have a greater concentration of branch-chained amino acids (BCAAs), which are crucial for muscle protein synthesis (van Vilet, Burd, & van Loon, 2015). However, there is no conclusive evidence suggesting that an omnivorous diet improves athletic performance to a greater extent than a vegetarian/vegan diet.

In fact, there is typically no significant difference in the results of an omnivorous diet vs. a vegetarian diet on performance. Evident by the study conducted by Craddock, Probst, & Peoples (2016), factors such as strength, aerobic performance and anaerobic performance did not differ between the groups. This was expected as no change is observed in the maximal aerobic and anaerobic capacity of such athletes, despite higher oxygen consumption at given workloads by individuals on the vegetarian diet (Hanne, Dlin, & Nrotstein, 1986; Hietavala, Puurtinen, Kainulainen, & Mero, 2012). Additionally, levels of physiological markers, creatinine and carnosine, for muscle-building were similar between both groups (Baguet et al., 2011).

Essentially, this research demonstrates that an omnivorous diet is not a requisite for attaining peak performance in exercise. Rather, a vegetarian diet is capable of achieving the same results, with the added health benefits of not consuming meat products and preserving the environment. To maximize performance as an athlete on a vegan diet, intake of lentils, greens, nuts and other plant products are encouraged (Fuhrman & Ferreri, 2010). Additionally, while not required, supplements for BCAAs and vitamins are always available, further disincentivizing the need to consume meat.

Weight Loss

Any active individual is largely concerned about managing their weight and BMI. Considering that nearly two-thirds of America citizens are classified as either overweight or obese, the topic of diet becomes increasingly important in promoting weight loss (Hedley et al., 2004). Vegetarian, similar to low-fat diets, has been proven effective in the short-term for reducing weight, alongside other benefits and effects. In a 14-week prospective study conducted by Turner-McGrievy and colleagues (2007), a vegan diet was significantly greater at promoting weight loss when compared to the National Cholesterol Education Program diet. Additionally, vegetarians and vegans typically have a lower BMI when compared to omnivores (Alewaeters, Clarys, Hebbelinck, Deriemaeker, & Clarys, 2005). These results are consistent even without placing a limit on portion size and calorie consumption, as it is assumed that vegans receive a decrease in dietary energy density and lower energy consumption by vegans (Barnard, Scialli, Turner-McGrievy, Lanou, & Glass, 2005). However, more studies are required to examine the effects of a vegan diet on weight in the long-term.

Cardiovascular - Karan

Several studies have looked at the health risks associated with the consumption of meat. Meat contains saturated fat and red meat has been found to contain more saturated fat than most other sources of proteins such as fish and chicken. It has been shown that large amounts of saturated fat is responsible for raising one’s cholesterol level which could lead to an increased risk of heart disease. In a large European study done in 2013, the relationship between the consumption of meat and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases in 448,568 male and female from 10 countries was published. They confirmed that an increased consumption of red meat increased the mortality by 14%. Similar trend was observed in processed meat. It was shown that consumption of processed meat increased the mortality by approximately 44%.

Trimethylamine N-oxide

Aside from saturated fats, some recent studies have shown that people with high consumption of red meat have higher levels of a metabolite called trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO). TMAO is a toxin that is colorless and is a class of amine oxide, which is usually found in high concentrations in marine organisms. The study showed that people who ate red meat regularly had triple the amount of TMAO compared to people who ate plant-based products. TMAO has also been found to increase the risk of heart disease, stroke and several other cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, the American Heart Association recommends everyone to limit the amount of red meat they consume.

Environmental Factors

Different diets can have varying effects on the environment since various types of foods are included in each one. An omnivorous diet can cause significantly more damage to the environment than a vegan or vegetarian diet since meat and dairy have many negative effects. With the population growing and the demand for meat increasing, the impacts that the meat industry has on the environment is becoming more severe.

Carbon Emission Impact

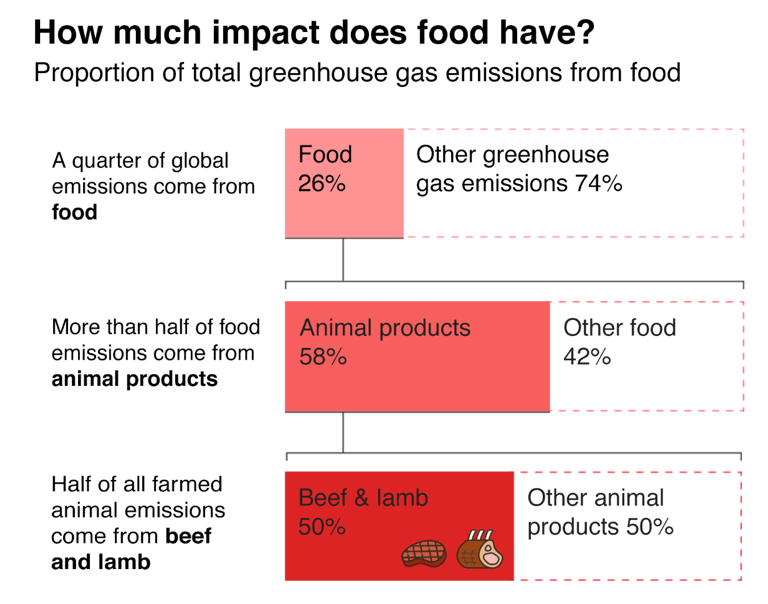

Unfortunately, food production is responsible for about a quarter of human-related emissions and more than half of food emissions are from animal products (Harribin, 2019). Changing to a vegetarian diet can reduce carbon dioxide emissions by over 1200kg per year and a vegan diet can reduce over 1500kg of CO2 (Rosi et al., 2017). Figure FILL IN LATER shows how much of the total greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are connected to food, with beef and lamb causing most amount of the emissions. Beef and lamb produce 10 to 40 times more GHG emissions than vegetables and grains and 20% of overall US methane emissions are produced by cattle (Scheer & Moss, 2011).

Figure FILL IN LATER: Impact of Food on Greenhouse Gas Emissions. A quarter of total emissions are from food while more than half of food emissions are from animal products, especially beef and lamb.

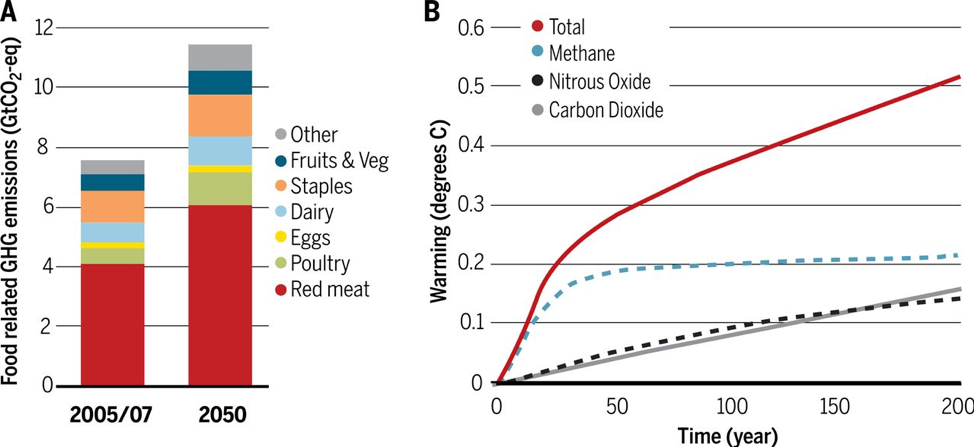

The total amount of gas emissions is expected to steadily increase with the climate warming and meat consumption increasing. Methane increases quickly in the atmosphere but plateaus after about 2 decades while nitrous oxide grows for two centuries, before slow growth occurs. Carbon dioxide is the major contributing factor to harming the environment since it will continue to grow throughout 2 centuries and will increases as long as emissions continue (Godfray et al., 2018).

Figure FILL IN LATER: Relationship between Meat and Climate Change. Figure FILLA: Compares food related emissions created by various foods during 2005-2007 and the predicted, 2050. Figure FILLB: Demonstrates how with increasing temperatures, different types of gases will continue to stay in the environment.

Water Usage

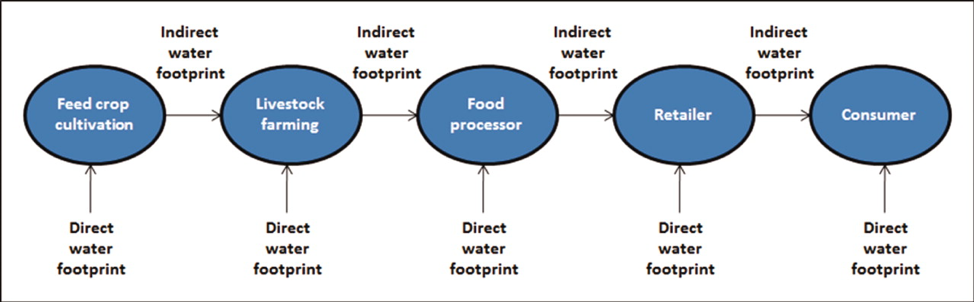

Switching to a vegetarian or vegan diet can reduce the food-related water footprint created by people by more than 36% in certain countries (Hoekstra, 2012). Water footprint of a product is the volume of freshwater used to produce that product. 98% of the water footprint of animal products is from water usage for feeding the animals (Hoekstra, 2012). Cattle typically live in large open fields and require a lot of feed to reach their slaughter weight. In order to produce the large amount of feed required to have the cattle grow, the amount of water usage is constantly on the rise. Figure FILL is a representation of all the different steps where water is required for animal products.

Figure FILL: Direct and Indirect Usage of Water. Water is required in many steps for producing and maintaining animal products. This includes food crop cultivation, livestock farming, food processing, selling and consuming the animal products.

When comparing diets, to produce food for an omnivore for one day, 3,600L of water is required. Compared to the 2,300L of water for food production for a vegetarian or vegan, there is a 36% reduction between the two diets (Hoekstra, 2012). This comparison shows the drastic water usage difference between the two diets and emphasizes the changes that can be done to help save water and help the environment.

Other Environmental Impacts

In order to keep livestock healthy and to sell them, antibiotics are fed to the animals to keep them healthy which has formed antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria that can threaten humans and the environment (Scheer & Moss, 2011). Currently, 65% of deforestation in the Amazon rainforest is connected to cattle ranching and over 440 million hectares of the world is used for animal production (Recanati et al., 2015). Since cattle and other animals require large amounts of land to roam around, many natural habitats are forced to become grassland for them to survive. Habitats are also destroyed to grow grain and soya for cattle consumption (Godfray et al., 2018). This reduces plant species diversity and also increases soil erosion, leading to further biodiversity loss and causing carbon dioxide in the soil to be re-released into the atmosphere (Godfray et al., 2018). Additionally, the nitrogen and phosphorus in animal manure are harmful to aquatic ecosystems and human health if not properly eliminated. Industries can use the animal manure as artificial fertilizer to reduce the amount of energy used to create fertilizer and help lower greenhouse gas emissions (Godfray et al., 2018). The impacts of the meat industry on the environment is extremely harmful and many negative effects can be avoided if meat consumption is decreased and more people are aware of the impacts of a omnivore diet.

Long-Term Impact on Health

Multiple studies have been conducted to determine the long-term impacts of veganism. However, it is impossible to accurately generalize impacts on populations worldwide due to biological, geographical, and environmental variations. The following are some health-related long-term impacts of veganism from a study conducted in western countries by Appleby and Key in 2016:

✔ BMI: Lower by up to 2 kg/m2 across all adult age groups, with a lower prevalence of obesity and weight gain.

✔ Diabetes: The relatively low BMI plays a role in the prevention of Type II Diabetes as well as the management of blood-insulin levels.

✔ Cardiovascular disease: Lower risk of cardiovascular-related conditions due to:

⇒ Lower LDL cholesterol

⇒ Lower BMI

⇒ Lower mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure

✘ Osteoporosis and Fracture Risk: Bone-mineral density is 4% lower and a 30% higher risk of fracture compared to meat-eaters

✔ Cancer: Lower risk of:

⇒ Stomach Cancer

⇒ Colorectal Cancer

⇒ Lymphoma

✔ Other diseases and conditions: Lower risk of:

⇒ Kidney stones

⇒ Diverticulitis

⇒ Degenerative arthritis

⇒ Hyperthyroidism

★ Overall Life Expectancy: No significant difference

Long-Term Impact on Environment

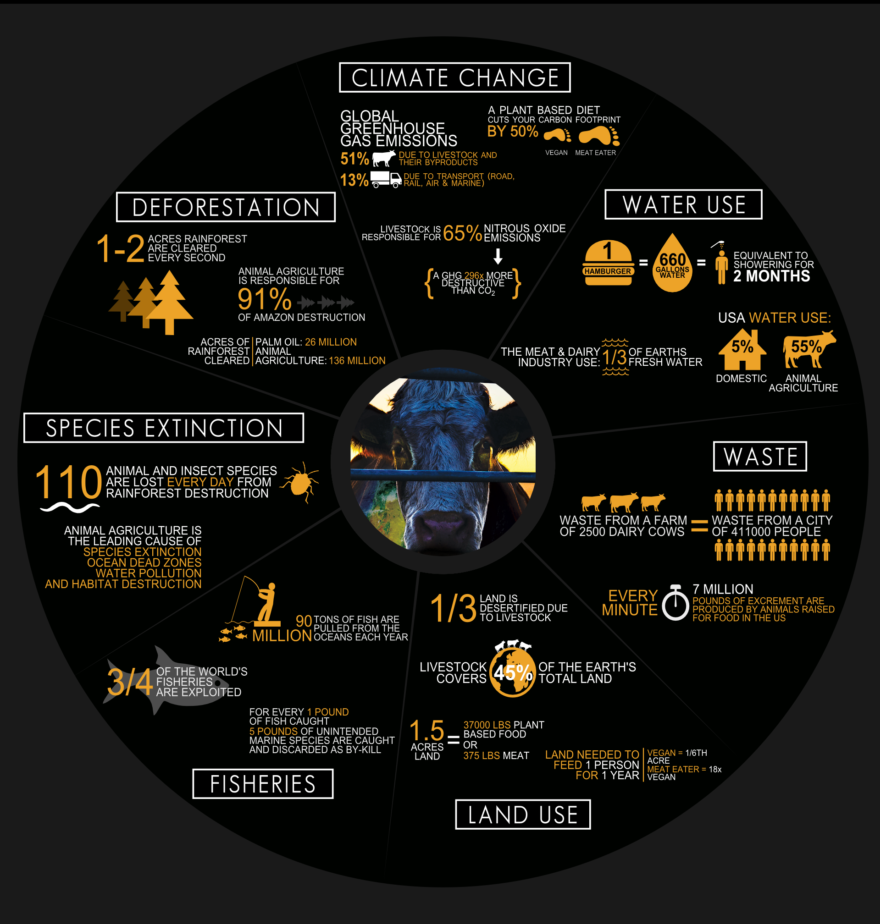

Veganism can have a long-term impact not only on humans but also on their surrounding environment. Figure 4. is an infographic that depicts the various emissions caused by animal agriculture and their negative impact on the environment.

Figure 4. Infographic by the creators of the documentary Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret which features some of the major impacts animal agriculture has on the environment. Some of these impacts include water consumption, deforestation, as well as species extinction. Animal agriculture also contributes to climate change due to the significant pollution caused by the emission of greenhouse gases and other waste products.

Research has shown that if humans turn away from meat and further towards veganism, then livestock-related greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced to up to 70% by the year 2050 (Springmann, Godfray, Rayner & Scarborough, 2016). This lower rate would also impact the economic side as the social cost of carbon (SCC) would also decrease. It is estimated that by the year 2050, having significantly more people following a vegan lifestyle would result in 1-31 trillion US dollars in economic benefits.

References

Appleby, P. N., & Key, T. J. (2016). The long-term health of vegetarians and vegans. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 75(3), 287-293. DOI: 10.1017/s0029665115004334

Alewaeters, K., Clarys, P., Hebbelinck, M., Deriemaeker, P., & Clarys, J. P. (2005). Cross-sectional analysis of BMI and some lifestyle variables in Flemish vegetarians compared with non-vegetarians. Ergonomics, 48(11-14), 1433-1444.

Baguet, A., Everaert, I., De Naeyer, H., Reyngoudt, H., Stegen, S., Beeckman, S., … & Taes, Y. (2011). Effects of sprint training combined with vegetarian or mixed diet on muscle carnosine content and buffering capacity. European journal of applied physiology, 111(10), 2571-2580.

Barnard, N. D., Scialli, A. R., Turner-McGrievy, G., Lanou, A. J., & Glass, J. (2005). The effects of a low-fat, plant-based dietary intervention on body weight, metabolism, and insulin sensitivity. The American journal of medicine, 118(9), 991-997.

Berry, J . (2019, August 27). Is red meat bad for you? Benefits, risk, research, and guidelines. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326156.php

COWSPIRACY: The Sustainability Secret. (2014). Retrieved from https://www.cowspiracy.com/infographic

Craddock, J. C., Probst, Y. C., & Peoples, G. E. (2016). Vegetarian and omnivorous nutrition—Comparing physical performance. International journal of sport nutrition and exercise metabolism, 26(3), 212-220.

Fuhrman, J., & Ferreri, D. M. (2010). Fueling the vegetarian (vegan) athlete. Current sports medicine reports, 9(4), 233-241.

Godfray, H. C. J., Aveyard, P., Garnett, T., Hall, J. W., Key, T. J., Lorimer, J., … & Jebb, S. A. (2018). Meat consumption, health, and the environment. Science, 361(6399), eaam5324. DOI: 10.1126/science.aam5324

Hanne, N., Dlin, R., & Nrotstein, A. (1986). Physical fitness, anthropometric and metabolic parameters in vegetarian athletes. Journal of sports medicine and physical fitness, 26(2), 180-185.

Harrabin, R. (2019). Plant-based diet can fight climate change – UN. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-49238749

Harvard Health Publishing. (n.d). Red meat, TMAO, and your heart. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/red-meat-tmao-and-your-heart

Hedley, A. A., Ogden, C. L., Johnson, C. L., Carroll, M. D., Curtin, L. R., & Flegal, K. M. (2004). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. Jama, 291(23), 2847-2850.

Hietavala, E. M., Puurtinen, R., Kainulainen, H., & Mero, A. A. (2012). Low-protein vegetarian diet does not have a short-term effect on blood acid–base status but raises oxygen consumption during submaximal cycling. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 9(1), 50.

Hoekstra, A. Y. (2012). The hidden water resource use behind meat and dairy. Animal frontiers, 2(2), 3-8. https://doi.org/10.2527/af.2012-0038

Janeiro M., Ramirez, M., Milagro, F., Martinez, J., & Solas, M. (2018). Implication of Trimethylamine N-Oxide (TMAO) in Disease: Potential Biomarker or New Therapeutic Target. Nutrients, 10(10), 1398. Doi: 10.3390/nu10101398

Mangels, R. (1999). Protein in the vegan diet. Simply Vegan, 5.

Mariotti, F., & Gardner, C. D. (2019). Dietary Protein and Amino Acids in Vegetarian Diets—A Review. Nutrients, 11(11), 2661.

Marsh, K. A., Munn, E. A., & Baines, S. K. (2012). Protein and vegetarian diets. The Medical Journal of Australia, 1(2), 7–10.

Quinn, S. (2016). Number of vegans in Britain rises by 360% in 10 years. The Telegraph, 18, 2016.

Recanati, F., Allievi, F., Scaccabarozzi, G., Espinosa, T., Dotelli, G., & Saini, M. (2015). Global meat consumption trends and local deforestation in Madre de Dios: assessing land use changes and other environmental impacts. Procedia engineering, 118, 630-638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2015.08.496

Richi, E. B., Baumer, B., Conrad, B., Darioli, R., Schmid, A., & Keller, U. (2015). Health risks associated with meat consumption: a review of epidemiological studies. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res, 85(1-2), 70-78.

Rosi, A., Mena, P., Pellegrini, N., Turroni, S., Neviani, E., Ferrocino, I., … & Maddock, J. (2017). Environmental impact of omnivorous, ovo-lacto-vegetarian, and vegan diet. Scientific Reports, 7(1), 1-9. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-06466-8

Scheer, R. & Moss D. (2011). How Does Meat in the Diet Take an Environmental Toll? Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/meat-and-environment/

Springmann, M., Godfray, H., Rayner, M., & Scarborough, P. (2016). Analysis and valuation of the health and climate change cobenefits of dietary change. Proceedings Of The National Academy Of Sciences, 113(15), 4146-4151. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1523119113

Turner‐McGrievy, G. M., Barnard, N. D., & Scialli, A. R. (2007). A two‐year randomized weight loss trial comparing a vegan diet to a more moderate low‐fat diet. Obesity, 15(9), 2276-2281.

Velasquez, M., Ramezani, A., Manal, A., &Raj, D. (2016). Trimethylamine N-Oxide: The Good, the Bad and the Unknown. Toxins, 8(11), 326. Doi:10.3390/toxins8110326

Van Vliet, S., Burd, N. A., & Van Loon, L. J. (2015). The skeletal muscle anabolic response to plant-versus animal-based protein consumption. The Journal of nutrition, 145(9), 1981-1991.