This is an old revision of the document!

Table of Contents

Global Burden of Disease: Coronary Artery Disease

Introduction

What is the Global Burden of Disease?

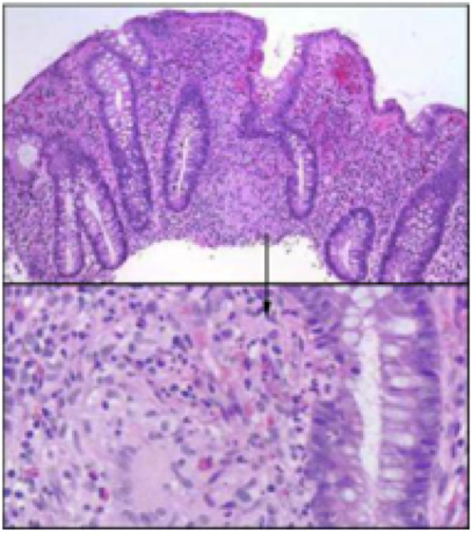

Crohn disease is an idiopathic, chronic inflammatory process of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract which affects any parts of the tract ranging from the mouth to the anus. It is believed to be the result of an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators. Some factors which encourages this imbalance are genetic susceptibility and environmental triggers. Hence, there is no real single factor that induces this intestinal inflammation.

Signs and symptoms include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, and weight loss. Usually, these symptoms induce complications by intestinal fistulization and obstruction. Additionally, individuals diagnosed with this risk are at a greater risk of developing bowel cancer. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/copd>

Coronary Artery Disease

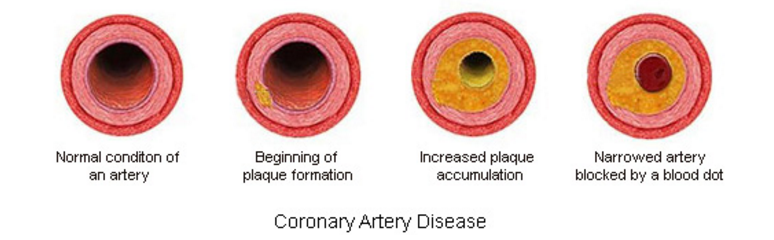

Coronary Artery disease (CAD), also known as Coronary Heart Disease (CHD) and Ischaemic heart disease is the largest contributor to cardiovascular diseases (Wong 2014). The diseases are characterized by: angina (chest pain), shortness of breath and myocardial infarction which may contribute to patient mortality. One of the main causes of CAD is atherosclerosis which is characterized by gradual thickening of the coronary artery walls. This occurs when plaque, composed of debris, fat and organic substances accumulates inside the arterial walls, leading to narrowing and hardening of the blood vessels.

Other risk factors include hypertension, cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus or elevated glucose levels, increased cholesterol levels, and obesity (Wong, 2014). Specifically, a dangerous combination of poor nutrition and lack of physical exertion can lead to many of these risk factors. Current research suggests preventive measures are the most beneficial in reducing an individual's risk for developing CAD; this includes proper nutrition and doing regular exercise. Furthermore, additional treatment options include the use of medication such as beta blockers, nitrates, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and antiplatelets. Surgery is a more invasive option for those afflicted with multiple blockages and the goal is to improve circulation of blood towards the heart.

Epidemiology

CAD is a major cause of death and disability in developed countries, although mortality rates have been observed to be decreasing over the last decades in western countries (Sanchis-Gomar et al 2016). Despite the decline, CAD still causes approximately one-third of all deaths in people older than 35 years. The Framingham Heart, which is an ongoing population-based cardiovascular cohort study concludes the many risk factors that contribute to CAD. The study concluded that men over the age of 38 had 1.5 times greater risk of developing atrial fibrillation than women (Benjamin et al 1994). A follow up of the Framingham study based on 44 years of data and observation of the offspring of the original study members was conducted. Results indicated individuals aged over 40, the lifetime risk of developing CAD was 49% in men and 32% in women. The lifetime risk for 70 years old individuals was 35% in men and 24% in women. Lastly, for total coronary events, the incidence rose steeply with age, with women behind men by approximately 10 years.

The 2016 Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics update of the American Heart Association reported that 15.5 million people over 20 years of age in the USA have CAD, with the prevalence increasing with age for both sexes (Sanchis-Gomar et al, 2016). The results of the data collected on CAD and MI is illustrated in the graphs where the prevalence for men is observed to be much greater than women. Furthermore, in a 2009 report based on data from National Health and Nutritional Survey (NHANES), myocardial infarction prevalence was observed in middle aged individual (35-45 years of age) during the 1988-1994 and 1999-2004 time periods. The results indicated a higher prevalence in men compared to women, but the trend declined for the former over time.

The World Health Organization released estimates of the global and regional burden of disease, which included 20 leading causes.The data was collected for 2000 and 2012, with a reported increase in DALY being observed both globally and in regions such as Southeast Asia, the Eastern Mediterranean and the western pacific region. The global rank of ischemic heart disease increased from being the third leading cause of death in 2000 to the first leading cause of death in 2012 (World Health Organization, n.d.) Although the global burden of coronary artery disease was dominant in western countries during the early 20th century, the burden now lies in specific Asian and middle-Eastern regions (Wong 2014). The global ischemic heart disease DALY data collected for both sexes indicates a high concentration in central asia, North Africa and West Europe.

Pathophysiology

Coronary Artery Anatomy

Arteries are shaped like hollow tubes and have muscular walls lined with a layer of cells known as the endothelium (Libby & Theroux, 2005). These walls are smooth and elastic and provide a physical barrier between the walls of the artery and the blood stream (Cleveland Clinic, 2017).

Atherosclerosis

One of the leading causes of CAD is atherosclerosis or the gradual thickening of the walls of the coronary arteries (Cleveland Clinic, 2017). Atherosclerosis occurs when plaque builds up inside of arterial walls, causing the narrowing and hardening of these blood vessels (Cleveland Clinic, 2017).

As individuals age, cellular debris begins to stick to the vessel walls. The amalgamation of debris, fat and other substances combine to create what is known as ‘plaque' (Libby & Theroux, 2005). Plaque can be composed of many things, but often includes cholesterol, fat substances, metabolic waste, calcium, and fibrin (a clotting compound found in the blood) (Libby & Theroux, 2005). The inside of the arteries develop plaques of different shapes and composition as a person ages (Libby & Theroux, 2005). Most plaques have a fibrous ‘cap’ covering a softer interior. If the cap either cracks or is torn, the soft inside is exposed, and platelets form a clot around the plaque (Cleveland Clinic, 2017). This can cause irritation in the endothelium, and even cause a disruption in function where the artery contracts inappropriately and thus narrows the artery even more (Cleveland Clinic, 2017).

Once broken off, the clot may disintegrate into smaller components, thus restoring normal blood flow patterns (Cleveland Clinic, 2017). However, what often happens is the thrombus (blood clot) begins to block blood supply to the heart muscle causing what is known as a coronary occlusion. This would be an acute cause of CAD, as it is the result of a sudden rupture of a plaque and formation of a thrombus (Cleveland Clinic, 2017). The alternate cause of CAD is of chronic origin- the coronary artery is simply narrowed over time and blood supply is slowly limited (Cleveland Clinic, 2017).

Atherosclerotic Lesions

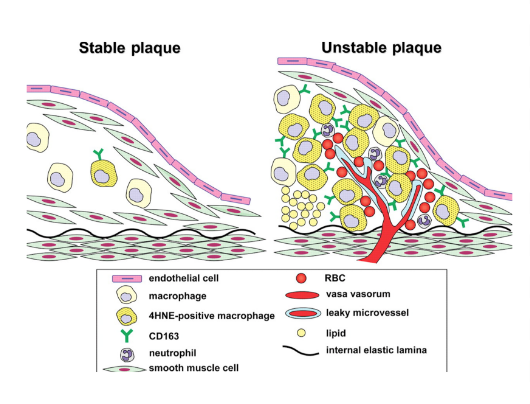

Beginning as smaller lesions, early atherosclerotic lesions can then rapidly enlarge into plaques in individuals with coronary risk factors (Fuster et al., 1992). Atherosclerotic lesions, or atheromata, are the asymmetric thickening of the intima (the innermost layer of the artery). Atheromata are composed of cells, connective tissue elements, lipids, and cellular debris (Fuster et al., 1992). The core of an atheroma is made up of immune cells such as T-cells and macrophages, which can produce inflammatory cytokines, coagulation factors, radicals, and proteases when activated. These factors can then, in turn, destabilize lesions and induce ischemic events (Fuster et al., 1992).

Ischemic Events & Plaque Disruption

An ischemic event occurs when there is a restriction or a reduction in blood supply to the tissues, causing a shortage in the materials needed for cellular metabolism in the cells (e.g. oxygen and glucose) (Fuster et al., 1992). In CAD, there are a variety of ways in which ischemic events can be triggered (Fuster et al., 1992).

1) Lipid-Rich Plaques - Small atherosclerotic plaques are often made up of a crescent-shaped mass of lipids, and are relatively small and soft due to both their high concentration of cholesterol and the presence of the chemical compound ester. If there is a change in shear force around the area of stenosis or a sudden change of intraluminal pressure, these small plaques may be disrupted and cause an ischemic event (Fuster et al., 1992).

2) Macrophages - Responsible for the uptake and metabolism of lipids, macrophages are thought to play a role in the development of plaques. Macrophages may also play a role in plaque formation because they enhance the transport of cholesterol, and release a mitogenic factor that helps the proliferation of smooth-muscle cells. They play a role in plaque disruption as they release proteases that digest the extracellular matrix, which can then cause a plaque to be released (Fuster et al., 1992).

3) Vessel Wall Stress - Plaques may also be disrupted due to alterations on or within plaques. Some plaques, known as fissured plaques, contain a fibrous cap that when under tensile stress, can rupture due to the lack of collagen support under the cap. Other forms of plaques may be distressed by vessel wall stress due to the disturbed blood flow pattern due to areas of stenosis (narrowing). This altered pressure and flow may cause plaque tearing. Finally, plaques may also be disrupted by the bending and twisting of the artery during contractions (Fuster et al., 1992).

Symptoms

CAD can present itself in a variety of ways, including:

1) Chest Pain (Angina) is typically described as tightness or pressure in your chest and normally occurs in the middle or left side. Typically induced by stress, the pain usually subsides within minutes of reducing exertion. Women tend to feel the pain in the neck, arm, or back instead of the chest (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2015).

2) Shortness of Breath is due to the obstruction or stenosis of arteries. In these cases, the heart is unable to pump blood to meet the needs of the body which can cause extreme fatigue (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2015).

3) Heart Attack or Myocardial Infarction (MI) can occur if the coronary artery is completely occluded. Symptoms of a heart attack include a crushing or squeezing pressure in the chest, pain in your shoulder or arm, shortness of breath, nausea, denial, or sweating. Women often experience different symptoms than men, such as pain in the neck or jaw. Heart attacks can also occur without any of the hallmark warning signs or symptoms, these are known as ‘silent Heart Attacks’ (Mayo Clinic Staff, 2015).

Risk Factors

Modifiable and Non-Modifiable Risk Factors There are numerous factors which can increase one’s risk of developing CAD. Physiologically, high cholesterol, high blood pressure, and high blood sugars (diabetes) have all been reported as key risk factors for CAD (Coronary Artery Disease Risk Factors, 2016). In addition, one’s risk for developing CAD increases greatly as the number of risk factors an individual possess increases (CADRF, 2016). Fortunately because of the advances in medicine, there are numerous pharmacological treatment options available for combating each and every single one of these aforementioned risks. Furthermore, there are also non-modifiable risk factors for which someone can do nothing about. These include age, sex, and ethnicity (CADRF, 2016).

Lifestyle Factors However, the truly problematic risk factors are the ones that are sociological in nature for which there are no easy fixes. For example, it has been shown that a combination of poor nutrition and lack of physical activity can lead to the development of obesity which can greatly increase one’s risk for developing CAD (Eckel & Krauss, 1998). It can seem obvious to state that if an obese individual wanted to lower their risk factors for CAD that they should lose weight. This simple statement is extremely difficult to implement as long term clinically significant weight loss is seldomly achieved (Wing & Phelan, 2005).

Healthcare Factors To further complicate the problem, individuals in developing nations simply lack the access to affordable and reliable healthcare facilities to adequately treat their chronic conditions. In addition, healthcare systems around the world are reactionary in nature and tend to treat diseases only when the patient manifests symptoms rather than preventing the disease in the first place. This approach to healthcare is especially problematic for chronic diseases such as CAD for which there appears to be no immediate cure but rather the only plausible medical solution is to manage the current conditions to not allow any advancement in the disease. Unfortunately, this approach to disease is extremely expensive, and thus simply impractical for many living in developing nations. Thus without the proper medical management of CAD in addition to rising global life expectancies, especially in predominantly developing parts of the world, the global burden of CAD will undoubtedly increase for the foreseeable future (World Health Organization, n.d.). The most effective long term strategy for combating CAD should focus on preventing any and all risk factors associated with CAD from occurring in the first place.

Exacerbating Factors

Intercurrent infections

Intercurrent infections (both upper respiratory tract and enteric infections) have been seen to exacerbate Crohn’s disease. Many studies have examined the interaction between infections and CD and have shown that infections can initiate the onset and relapse of inflammatory bowel diseases (including CD). The disease also puts patients at a higher risk of infection and the medications to treat CD and further increase the risk. The lack or poor response to vaccinations can also play a role in infections (Irving, & Gibson, 2008).

Cigarette Smoking

Smoking cessation has a beneficial effect to patients with Crohn’s disease. Studies have shown patients with Crohn’s disease who stopped smoking for more than 1 year had a more benign disease course than if they had never smoked. Considering the rate of flare-up and therapeutic needs, disease severity was similar in patients who had never smoked and those who stopped smoking, and both had a better course than patients who continued smoking (Cosnes., Beaugerie., Carbonnel., & Gendre, 2001).

Stress Many patients and family members report stress being an influencing factor for the onset and progression of CD (Hanauer., & Sandborn, 2001). However, there have been not studies that support this relation. Researchers have not been able to link trauma events or a stressful life to the development of CD. More research must be done in this area of study to form more conclusive evidence.

Medications- Prednisone

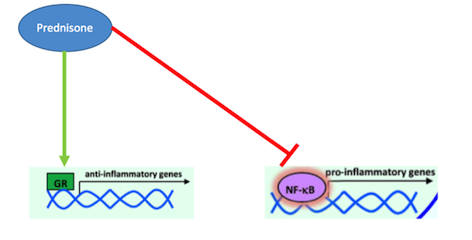

What is Prednisone? Prednisone is a corticosteroid that acts as a glucocorticoid receptor agonist in order to treat inflammatory diseases, such as Crohn’s (Barnes, 1998). Inflammation of the digestive tract is a common symptom in Crohn’s disease patients due to the pathophysiology of this disease. In the past, corticosteroids like Prednisone have been used for their immunosuppressive and anti-inflammatory properties (Jobin & Sartor, 2000). They are able to decrease inflammation by inhibiting the actions of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thus decreasing recruitment of white blood cells, like monocytes and neutrophils, which cause inflammation (Auphan et al., 1995). Many studies have conclusively shown that pro-inflammatory cytokine, such as TNF- alpha and IFN-gamma, are responsible for the inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract that is present in Crohn’s disease patients (Wakefield et al., 1991). Typically, the anti-inflammatory response in the body is controlled by glucocorticoids. When their release is normally stimulated in the body, they will bind to intracellular, cytoplasmic glucocorticoid receptors (Farell & Kelleher, 2003). These receptors will dimerize upon binding and immediately be transported to the nucleus where the regulate the transcription of target genes through block transcription of the promote NF-kappa-B. As mentioned earlier, NF-kappa-B is a potent transcription factors that, when activated, will lead the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-alpha (Beato, Herrlich & Schutz, 1995). Research into other inflammatory disorders, such as asthma and irritable bowel syndrome, have proven that these diseases are caused by glucocorticoid resistance, which leads to an un-regulated inflammatory response, caused by increased cytokines which increase recruitment of white blood cells (Barnes, 1998). Since inflammation is a primary part of the pathophysiology of Crohn’s disease, Prednisone can effectively manage these symptoms by binding to glucocorticoid receptors and promoting their activation. By doing do, Prednisone is able to inhibit inflammatory cytokine production and thus ultimately decrease white blood cell recruitment and inflammation (Barnes, 1998).

Effectiveness

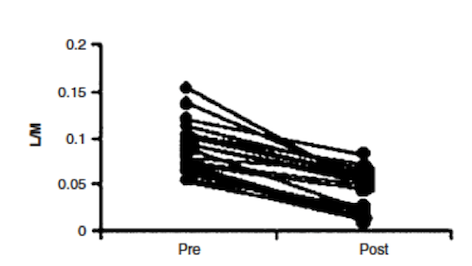

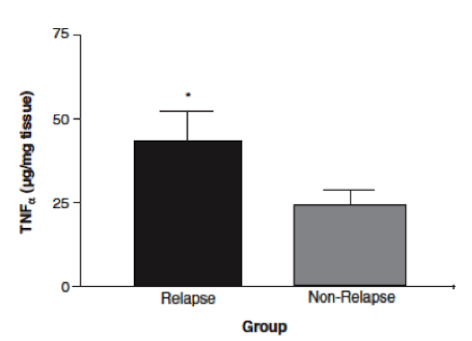

In a study done by Wild et al. (2003), effectiveness of Prednisone in the treatment of Crohn’s disease pathophysiology was illustrated. By measuring intestinal permeability and TNF-alpha levels, they were able to determine that Prednisone was effective in reducing bowel inflammation in Crohn’s disease patients. Typically, in Crohn’s disease, increased intestinal permeability to sugars and macromolecules has been illustrated (Hollander et al., 1986). Intestinal permeability can be measured using urinary clearance of lactulose to mannitol (LM ratio). This is thought to be caused by the un-regulated inflammatory response in Crohn’s disease patients, which leads to decreases in epithelial barrier integrity and thus increased intestinal permeability (Wild et al., 2003). The anti-inflammatory properties of Prednisone were measured by muscle biopsies taken endoscopically (Scheinman et al., 1995). By comparing LM ratios and muscle samples to measure TNF-alpha levels, Wild et al. were able to observe the effects of Prednisone on Crohn’s disease pathophysiology. Results indicated that LM ratios were significantly reduced after treatment with prednisone. Prednisone was seen to reduce the LM ratio by approximately 50%, indicating it was able to induce remission; however, it was no proven to maintain remission after discontinuation of the drug (Wild et al., 2003). Additionally, TNF-alpha levels were measured by comparing levels of those who relapsed immediately and those who did not. In those that did not immediately relapse, there was a reduction in TNF-alpha levels, which is indicative of decreased inflammation (Wild et al., 2003). Overall, Prednisone was seen to aid in the induction of remission of Crohn’s disease patients, illustrated by reduced LM ratios (improved intestinal permeability) and TNF-alpha levels. However, once taken off the drug, Prednisone was not proven to be effective in maintaining remission, which is difficult because individuals cannot be on prednisone for too long due to side effects, which will be discussed in the next section.

Side Effects

Corticosteroids, like Prednisone, are very effective drugs to treat the inflammation that is typically seen in Crohn’s disease patients. However, these anti-inflammatory properties are caused by the suppression of the immune system, which has many side effects on the body (Malchow & Brandes, 1984). Pro-inflammatory cytokines, like TNF-alpha, promote vasodilation and increased white blood cell migration of injury suite within the body (Scheinman et al., 1995). Since Prednisone blocks the transcription of TNF-alpha within the body, it is able to decrease the inflammatory response within the bowels of Crohn’s disease patients that TNF-alpha causes, it also supresses the other effects of the drug. A typical side effects that patients on Prednisone may experience is high blood pressure, which is associated with water retention (1 Malchow & Brandes, 19847). Additionally, decreased cytokine production prevents white blood cell recruitment to sites of injury and infection within the body, thus leading to an increase susceptibility to infections while on Prednisone because of this immunosuppressive effect (Coutinho & Chapman, 2011). Overall, Prednisone is very effective in treating Crohn’s disease pathophysiology when patients take it, but prolonged use is discouraged due to the side effects that accompany this drug.

Medications- Infliximab/ Remicade

What is Prednisone/ Remicade?

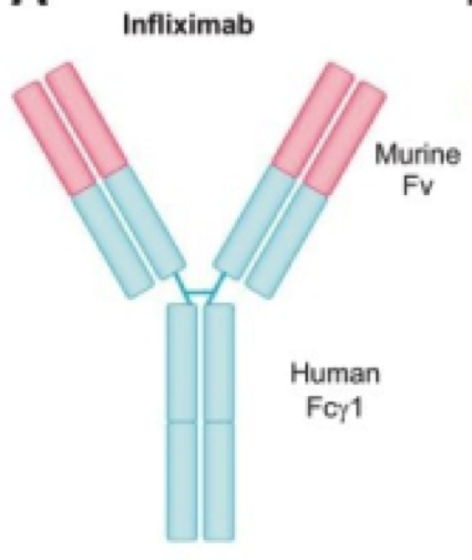

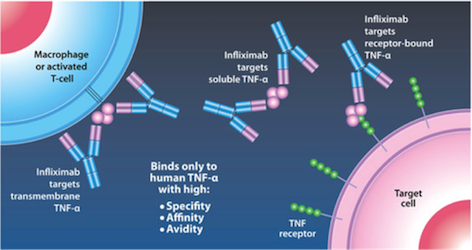

Kirman, Whelan, & Nielsen (2004) identify infliximab (trade name Remicade) is an IgG monoclonal antibody drug that targets TNF-alpha, a tumor necrosis factor. It is effective in ⅔ of Crohn’s Disease patients. The antibody is developed from mice and then replaced with human antibody domains (Kirman, Whelan, & Nielsen, 2004). Not only does infliximab treat Crohn’s Disease, but it also treats ulcerative colitis, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, plaque psoriasis (Janssen Biotech, 2016). Having an excess of TNF-alpha can cause the immune system to attack healthy cells in the GI tract leading to inflammation, and symptoms of Crohn’s Disease (Janssen Biotech, 2016).

Mechanism of Action Infliximab is given by IV infusion 6 times a year after 3 starting doses given at 0,2, and 6 weeks (Janssen Biotech, 2016). This drug can only be administered by healthcare professionals, and can even be delivered with other medications to reduce or eliminate side effects (Janssen Biotech, 2016). Infliximab binds to TNF-alpha expressing cells, as seen in Figure 8 (replace with real figure name), and precents TNF-alpha from binding to its receptor. The results of this drug are apoptosis of T-lymphocytes and monocytes, and down regulation of other inflammatory cytokines such as Th1 (Kirman, Whelan, & Nielsen, 2004). Apoptosis of monocytes is initiated by the CD95/CD95L signaling pathway and mitochondrial release of cytochrome C (Lügering et al., 2001). Cytochrome C release triggers the transcriptional activation of Bax and Bak, pro apoptotic regulators (Van Deventer, 2001).

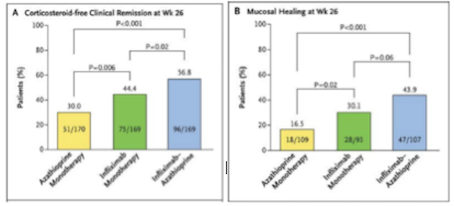

Effectiveness Infliximab is highly effective compared to other methods of treatments due to its high effectiveness and relatively low toxicity. When compared to another method of treatment, azathioprine, a purine analog working as an immunosuppressant, it has significantly better results (Colombel et al., 2010). Infliximab, seen in green on Figure 9 (replace with right number), is not more effective than a combined therapy, seen in blue. However, the combined therapy is much more toxic than the infliximab alone, therefore negates its effectiveness (Colombel et al., 2010). Furthermore, the increase in effectiveness of combined therapy is most likely due to the additive effect of using both drugs (Colombel et al., 2010).

Side Effects

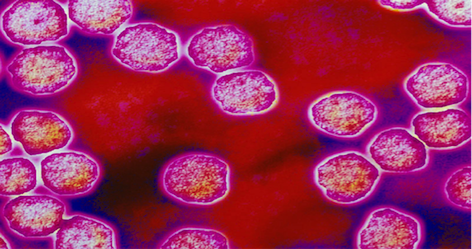

There is a higher risk of infection with mycobacteria, and thus increase risk of contracting tuberculosis (Antoni & Braun, 2002). This higher risk of infection is due to the patient's immunocompromised state when taking the drug, and to avoid serious illness patients need to be informed of their immunocompromised state and educated on necessary precautions by doctors before taking infliximab (Antoni & Braun, 2002). If patients take the signs of infection seriously and report it to their doctors they will receive antibiotics right away and chances of serious infection will be drastically reduced. When patients are traveling anywhere with high rates of tuberculosis they should not receive the treatment at all, however in the USA less than 1% of the population has tuberculosis. This treatment is not administered if the patient is planning on visiting countries with higher incidence of tuberculosis because it could result in them contracting the disease (Antoni & Braun, 2002). Infliximab use has also been loosely correlated with an increased incidence of lymphoma (Antoni & Braun, 2002). There is a rare chance of acute and delayed hypersensitivity reactions dye to development of human chimeric antibodies, but this is only in 10% of patients, with only 2.6% of patients discontinuing treatment due to serious infusion reactions. (Kirman, Whelan, & Nielsen, 2004). Infusion reactions symptoms are headache, dizziness and nausea (Antoni & Braun, 2002).

A positive side effect of Infliximab is that in reducing the TNF-alpha concentrations in the body, patients can see a reduction in the symptoms of other diseases. Things that have improved are rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and ankylosing spondylitis (Van Deventer, 2001).

Current Research

Current research is exploring the role of endogenous microbial communities in Crohn’s disease patients and healthy individuals. Researchers are concerned with dysbiosis, an imbalance in gut microbiota composition, and its association with several diseases, particularly inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s.

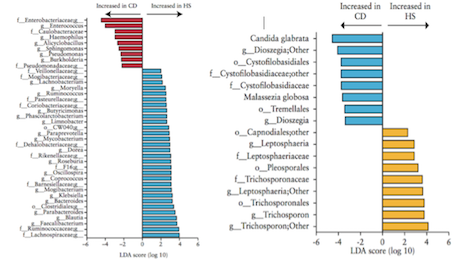

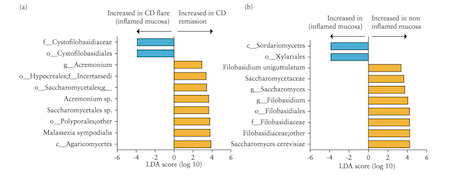

Liguori et al. (2015) A study by Liguori et al. (2015) analyzed bacterial and fungal microbiota biodiversity, and bacterial and fungal compositions present in the colonic mucosa of both Crohn’s patients and healthy subjects. Crohn’s disease was diagnosed in these patients according to classical clinical, endoscopic, and histological parameters (Liguori et al., 2015). Patients were considered healthy if they had no history or clinical symptoms of intestinal disorders or endoscopic or histological signs of irritable bowel disease (Liguori et al., 2015). Colonic mucosa specimens of Crohn’s patients were surgically acquired during oleo-colonic resection. Diseased specimens of the right colon, in both inflamed and non-inflamed mucosa, were collected. Specimens of healthy patients were sampled during colonoscopy using standardized biopsies of the right colon (Liguori et al., 2015). Liguori et al., (2015) observed a decline in biodiversity of Crohn’s disease patients samples compared with healthy subject samples. This result was true in both active and dormant Crohn’s patients, and in inflamed and non-inflamed mucosa. In Crohn’s patients, an increase of Proteobacteria was observed with a decrease of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes (Liguori et al., 2015). The most major differences between Crohn’s and healthy patients were observed in the Proteobacteria and Firmicutes phyla (Liguori et al., 2015). The results also revealed a significant increase of global fungus load in Crohn’s patients when compared with healthy subjects. This was observed in both inflamed and non-inflamed mucosa (Liguori et al., 2015).

Hoarau et al. (2016) Another study conducted by Hoarau et al. (2016) outlines five major findings.

1. Microbiotas of familial samples are distinct from those of nonfamilial samples (Hoarau et al., 2016) Gut samples collected from related individuals indicated greater similarities to each other regardless of their Crohn’s disease status. This provides insight for identifying organisms linked to the disease by comparing the microbiotas within affected and unaffected family members (Hoarau et al., 2016).

2. Abundance of potentially pathogenic bacteria is increased while beneficial bacteria are decreased in CD (Hoarau et al., 2016) An increased abundance of potentially pathogenic bacterial species, such as Escherichia coli and Serratia marcescens, were found in the samples of Crohn’s patients compared to healthy subjects. The team identified the abundance of 11 genera and 15 species that differed significantly in Crohn’s patients (Hoarau et al., 2016).

3. Candida tropicalis abundance is significantly increased in CD patients (Hoarau et al., 2016) Correlations between C. tropicalis abundance and anti-Saccharomyces cerevisiae antibodies (ASCA) levels were investigated because the yeasts of the genus Candida are described as immunogens for Crohn’s Disease biomarkers designated ASCAs. The ASCA level was significantly higher in Crohn’s patients than in the healthy group. C. tropicalis was also the only fungus that was positively associated with ASCA (Hoarau et al., 2016).

4. CD is associated with inter- and intrakingdom correlations (Hoarau et al., 2016) Hoarau et al. (2016) found several significant associations at the genus and species levels in both bacteria and fungi. Moreover, C. tropicalis demonstrated significantly positive associations with 13 bacterial species, including E. coli and S. marcescens (Hoarau et al., 2016).

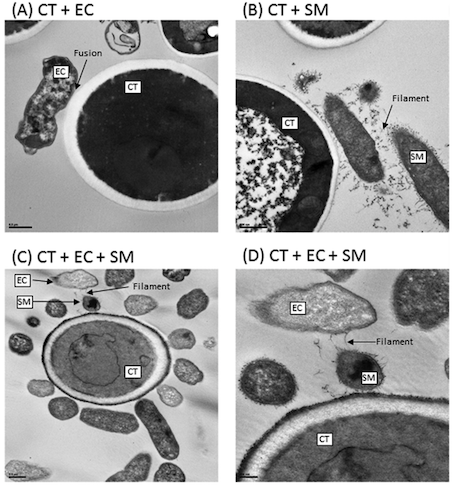

5. Biofilm formation mediates interkingdom interactions in CD (Hoarau et al., 2016) The analysis of a method called scanning electron microscopy (SEM) showed that biofilms formed by C. tropicalis alone comprised yeast forms while the biofilms formed by a combination of C. tropicalis and either E. coli or S. marcescens were enriched in fungal hyphae, a form of growth associated with pathogenic conditions (Hoarau et al., 2016).

Figure 12: Interactions of Transmission electron microscopy analyses of biofilms formed by C. tropicalis alone or in combination with E. coli and/or S. marcescens. (A) C. tropicalis plus E. coli; (B) C. tropicalis plus S. marcescens; (C) C. tropicalis plus E. coli plus S. marcescens (bar, 0.5 m); (D) C. tropicalis plus E. coli plus S. marcescens (bar, 200 nm). Modified from Hoarau et al. (2016).

Conclusion

A lot of research still needs to be done in order to better understand Crohn’s Disease. Genetic factors are linked with Crohn’s disease and increases the risk of diagnosis. The risk is much greater in individuals of similar familial background than those who are unrelated. Measles viral infections are also a confirmed risk factor of Crohn’s disease. Knowledge of risk may result in better preparation before diagnosis and more applicable treatments following diagnosis. Genetically susceptible individuals may engage in necessary measures to avoid triggering the disease symptoms while others may take precautions by receiving appropriate immunizations.

Awareness of certain factors that exacerbate Crohn’s is valuable for disease treatment and management. Avoiding habits which jeopardize optimal health in Crohn’s patients, such as cigarette smoking and use of contraceptives, may lead to fewer flares and discomfort experienced by these individuals. Crohn’s patients may also seek alternative methods to satisfy these habitual needs.

Treatment depends on the severity of each case, but medication is available for a large proportion of patients. Prednisone and infliximab/ remicade are both examples of effective pharmaceuticals prescribed to manage existing cases of Crohn’s. Current research suggest that there may be specific microbiota associated with Crohn’s disease. Recent findings on microbial communities is promising and may be pivotal point in Crohn’s disease history and treatment discovery, development, and approach.

References

Benjamin, E. J., Levy, D., Vaziri, S. M., D'Agostino, R. B., Belanger, A. J., & Wolf, P. A. (1994). Independent risk factors for atrial fibrillation in a population-based cohort: the Framingham Heart Study. Jama, 271(11), 840-844.

Brugts, J. J., de Maat, M. P. M., Danser, A. H. J., Boersma, E., & Simoons, M. L. (2012). Individualised therapy of angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors in stable coronary artery disease: overview of the primary results of the PERindopril GENEtic association (PERGENE) study. Netherlands Heart Journal, 20(1), 24-32. doi:10.1007/s12471-011-0173-6

Cleveland Clinic (2017). Coronary Artery Disease. Retrieved January 15, 2017 from http://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/coronary-artery-disease.

Coronary Artery Disease Risk Factors. (2016). National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Retrieved from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/hd

Eckel, R. H., & Krauss, R. M. (1998). American Heart Association Call to Action: Obesity as a Major Risk Factor for Coronary Heart Disease. Circulation, 97(21), 2099–2100. http://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.97.21.2099

Erbs, S., Linke, A., & Hambrecht, R. (2006). Effects of exercise training on mortality in patients with coronary heart disease. Coronary artery disease, 17(3), 219-225.

Fuster, V., Badimon, L., Badimon, J. J., & Chesebro, J. H. (1992). The pathogenesis of coronary artery disease and the acute coronary syndromes. New England journal of medicine, 326(4), 242-250.

Hennekens, C. H., Dyken, M. L., & Fuster, V. (1997). Aspirin as a Therapeutic Agent in Cardiovascular Disease A Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation, 96(8), 2751-2753.

Jolliffe, J., Rees, K., Taylor, R. R., Thompson, D. R., Oldridge, N., & Ebrahim, S. (2001). Exercise‐based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. The Cochrane Library. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800.

Libby, P., & Theroux, P. (2005). Pathophysiology of coronary artery disease. Circulation, 111(25), 3481-3488.

Lloyd-Jones, D., Adams, R. J., Brown, T. M., Carnethon, M., Dai, S., De Simone, G., … & Go, A. (2010). Heart disease and stroke statistics—2010 update. Circulation, 121(7), e46-e215.

Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med. 2006 Nov;3:e442.

Mayo Clinic Staff (2015). Coronary artery disease. Retrieved January 15, 2016 from http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/coronary-artery-disease/symptoms-causes/dxc-20165314

Murray CJL, Lopez AD. The Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Disease, Injuries and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Boston, Ma: Harvard University Press; 1996.

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.(2016). How is Coronary Heart Disease Treated ?. Retrieved January 13,2017 from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/cad/treatment#HeartHealthyEating

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.(2016). Percutaneous Coronary intervention.Retrieved January,13, 2017 from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/angioplasty

Premier Heart Care TT. (n.d.). Coronary Angioplasty (PCI).Retrieved January 18 2017 from http://www.premierheartcarett.com/coronary-angioplasty-pci/

Sanchis-Gomar, F., Perez-Quilis, C., Leischik, R., & Lucia, A. (2016). Epidemiology of coronary heart disease and acute coronary syndrome. Annals of Translational Medicine, 4(13).

University of Maryland Medical Center. (2017). Heart Bypass surgery-series. Retrieved January 18 2017 from http://umm.edu/health/medical/ency/presentations/heart-bypass-surgery-series

Wong, N. D. (2014). Epidemiological studies of CHD and the evolution of preventive cardiology. Nature reviews. Cardiology, 11(5), 276.

Wing, R. R., & Phelan, S. (2005). Long-term weight loss maintenance. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. http://doi.org/82/1/222S [pii]

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Estimates for 2000-2012: Disease Burden. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index2.html

World Health Organization (n.d.). 50 Facts: Global health situation and trends 1955-2025. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/whr/1998/media_centre/50facts/en/