Table of Contents

Presentation Slides

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Introduction

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a condition that is usually a result of either experiencing or witnessing a horrific situation. However, the term wasn’t coined until much recently, despite having been existing for hundreds of years. Early examples of PTSD include war veterans who experienced severe combat trauma from the Vietnam War. These individuals were not diagnosed with PTSD, but rather as “shell shock” or “soldier’s heart” (Crocq, 2000).

In 1980, the term PTSD was coined by the American Psychiatric Association who added it to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders third edition (DSM-III) (Crocq, 2000). The newest model is the fifth edition (DSM-5) which made changes to how PTSD is diagnosed. The severity of PTSD is dependent upon the degree of the response to the traumatic event that an individual experiences or witnesses, such as feelings of immediate helplessness, or extreme fear (Tan et al., 2011). PTSD has been shown to affect many war veterans, with 30% of Vietnam War veterans experiencing PTSD from combat (Tan et al., 2011). The most common sources of PTSD are a result of torture, war, sexual violence, and natural disasters (Friedman, 2014). PTSD rates in American men and women have been estimated at approximately 3.6% and 9.7% respectively (Friedman, 2014). The cost of PTSD to the United States is at a staggering $45 to $50 billion annually (Tan et al., 2011).

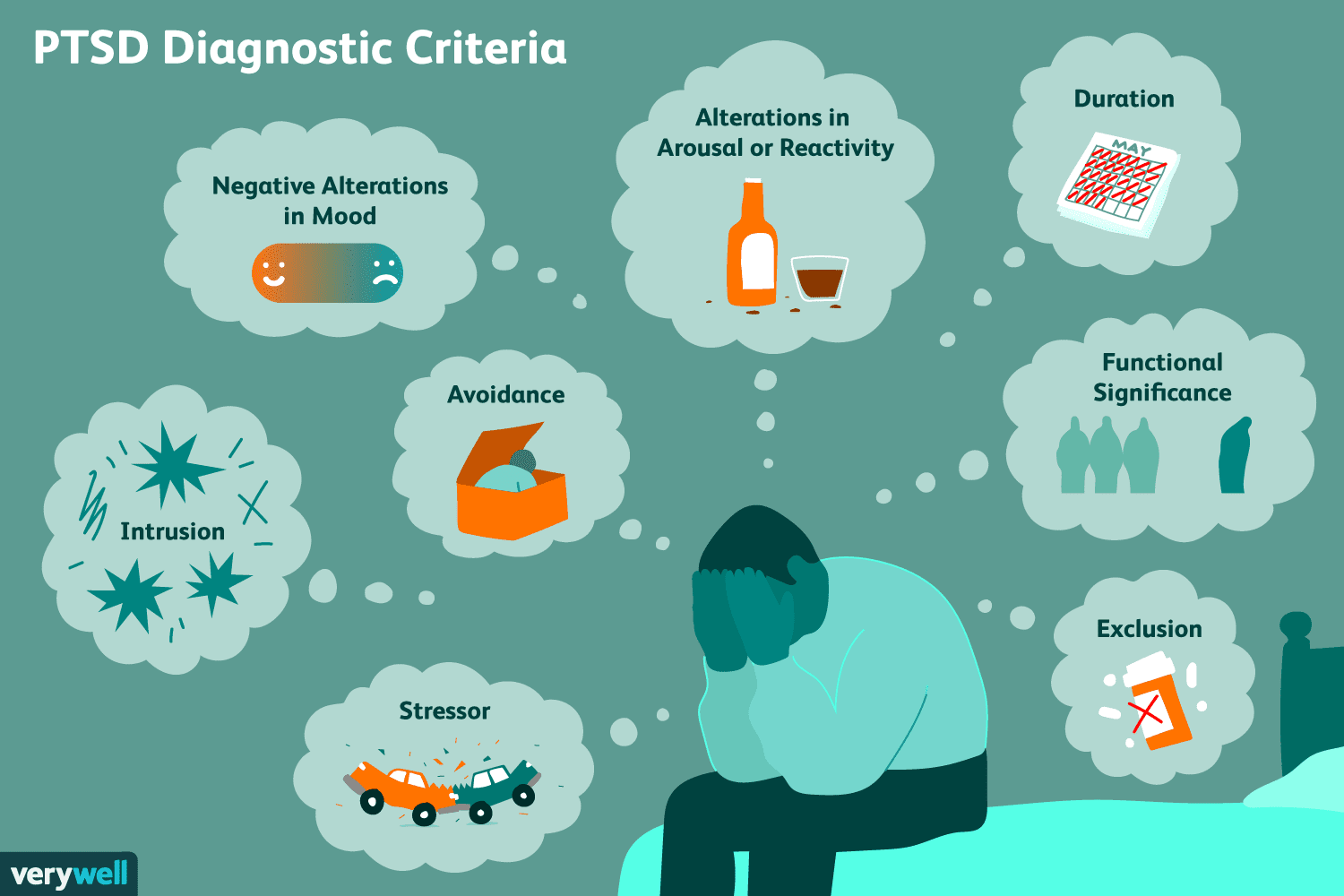

Diagnosis

The diagnostic criteria for PTSD has been modified recently, with the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) in 2013. This criterion involves a set of 20 questions that assesses an individual’s response to a stressful previous experience, also abbreviated as PCL-5 with PCL referring to the PTSD Checklist. This questionnaire asks about how much an individual is bothered by changes in their psychological thinking in the past month, as symptoms of PTSD can occur within a month after the experience. The scale for the responses to the questions is from 0-4, with 5 options being “not at all,” “a little bit,” moderately,” “quite a bit,” or “extremely” (Weathers et al., 2013). The 20 questions from the PCL-5 are asked about the stressful experience in the following condensed manner:

- Repeated memories

- Repeated dreams

- Flashbacks or imagining reliving the event

- Feeling upset upon being reminded

- Strong physical reactions when reminded

- Avoiding any feelings or memories associated

- Avoiding external reminders, such as people or places

- Having difficulty remembering key parts

- Negative thoughts about yourself or others

- Blaming yourself or others

- Strong negative feelings including anger and shame

- Losing interest in enjoyable activities

- Feeling detached from others

- Difficulty maintaining positive feelings

- Irritable or aggressive responses

- Making reckless decisions

- Being overly attentive

- Being easily startled

- Difficulty in concentration

- Difficulty with sleep

The responses for each of these 20 questions are scored from 0-4 as described earlier, and a minimum score range from 31-33 indicates that an individual has potential PTSD, with higher scores indicating a higher chance of having PTSD.

Symptoms

Symptoms usually begin within 3 months of the traumatic incident, but sometimes they begin later. For symptoms to be considered PTSD, they must last more than a month and be severe enough to interfere with functioning in relationships or work. The course of the illness varies from person to person. Some people recover within 6 months, while others have symptoms that last much longer. In some people, the condition becomes chronic. (National Institute of Mental Health [NIMH], n.d.)

The symptoms for PTSD are split into four categories which are re-experiencing symptoms, avoidance symptoms, hyperarousal symptoms, and cognition and mood symptoms. Re-experiencing symptoms are caused by a response to reminders of the traumatic event. These can include thoughts, words, objects, and situations. These can cause flashbacks and bad thoughts, which can lead to racing heart rate and sweating. Re-experiencing symptoms are characterized by intense emotional and physical responses after exposure to a traumatic reminder. Avoidance symptoms are caused by avoiding reminders of the traumatic event. This can involve changing one’s routine to avoid physical reminders and avoid thinking thoughts that remind a person about the traumatic event. For example, after a bad car accident, a person who usually drives may avoid driving or riding in a car.

Hyperarousal symptoms are constant after the traumatic event and involve a feeling stressed and angry. This also includes being easier to startle, being easier to anger, increased irritability, trouble sleeping, and trouble concentrating. Cognition and mood symptoms include ongoing and distorted beliefs about oneself or others, ongoing fear, horror, anger, guilt or shame, much less interest in activities previously enjoyed, and feeling detached from others (NIMH, n.d.; American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

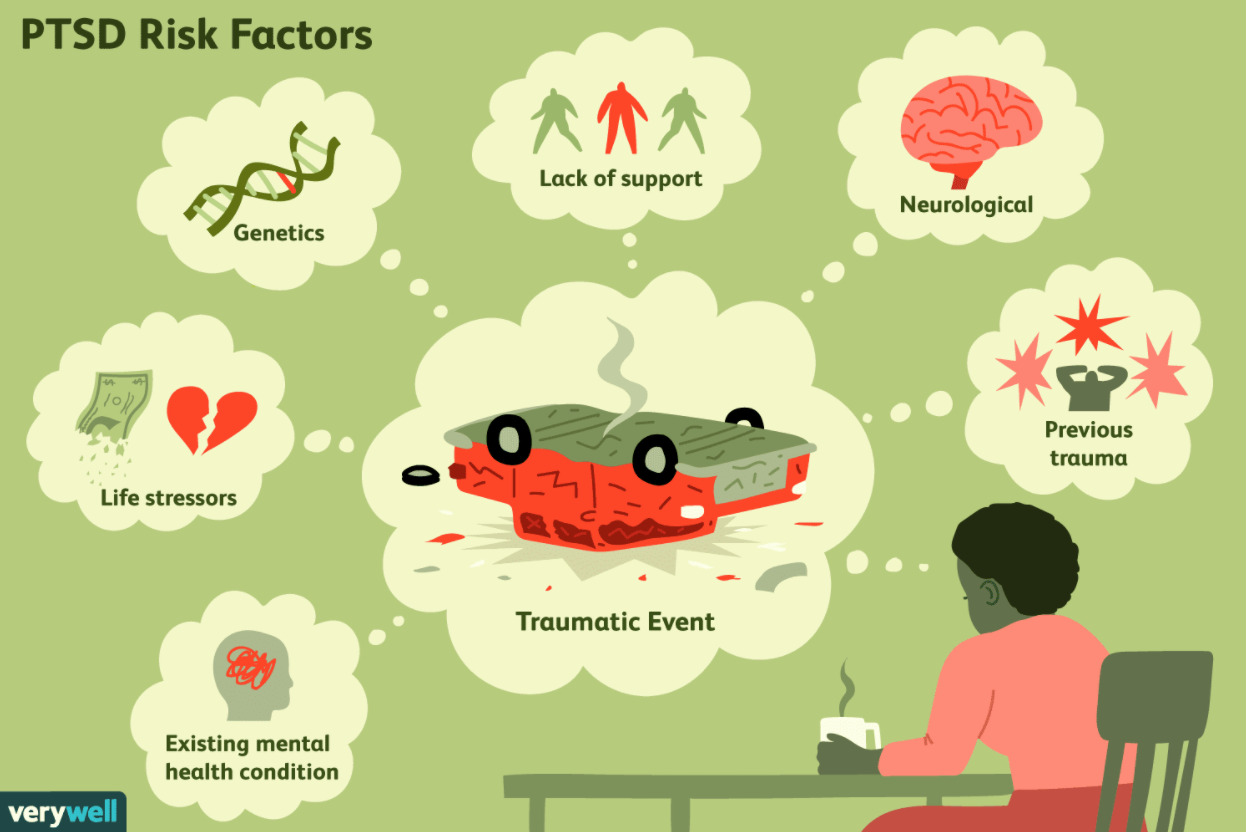

Risk Factors

People of all ages, races, ethnicity can have post-traumatic stress disorder. However, there are some risk factors that heighten an individual’s risk of developing PTSD after experiencing trauma. This can include experiencing intense or long-lasting trauma, or any other trauma that was experienced earlier in life, such as childhood abuse. Because children’s brains are still part of the developing process, childhood traumas are very serious and detrimental after they grow up. The trauma children experience during childhood can have a profound impact on the psychological, physiological, and social well-being. This is especially evident as children and teens have profoundly negative, adverse reactions to trauma. In addition, children exposed to trauma are less likely to seek treatment than adults (National Institute of Mental Health).

Another risk factor is having a job that increases one’s risk of being reminded of the traumatic events (e.g. One has a traumatic experience in the war and now has a job as military personnel and first responders). Another risk factor is when an individual has other mental disorders such as anxiety or depression or has a family background of mental illness. The individual may also have problems with bad coping mechanisms or substance misuse, such as excess drinking or drug use. The individual may also lack a good support system of family and friends. This is critical because PTSD suffers must have a strong, positive support system to overcome their trauma.

Trauma

Traumatic experiences differ from individual to individual. Everyone has their unique story, and how they react or cope with the trauma depends on their genetics, environment, upbringing, support system, and personality. However, most traumatic experiences can be classified into these categories:

- Combat exposure

- Childhood physical abuse

- Sexual violence

- Physical assault

- Being threatened with a weapon

- An accident

Pathophysiology

Genetics

Through family and twin studies, researchers discovered that risk for PTSD is associated with an underlying genetic vulnerability and that more than 30% of the variance associated with PTSD is related to a heritable component (Skelton, et al., 2012). Studies have examined key candidate genes in major genotypes in connection with PTSD, including serotonin, glucocorticoid, and apolipoprotein systems (Broekman, Olff, & Boer, 2007). However, because of the limitation of these studies and the complexity of the disorder, the findings have been inconclusive and provide little explanation in the pathophysiology behind PTSD (Broekman, Olff, & Boer, 2007).

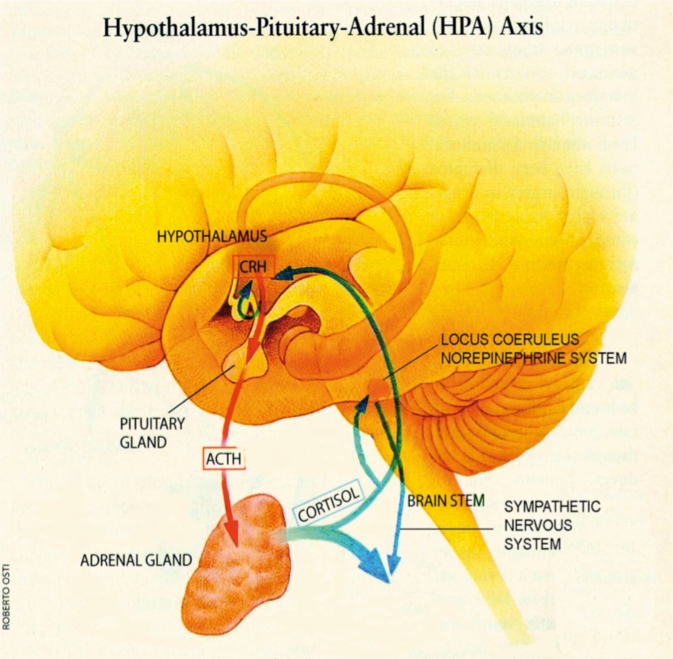

Endocrine Factors

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is the body's major response system for stress. The hypothalamus secretes corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which binds to receptors on pituitary cells. Pituitary cells then produce adrenocorticotropin (ACTH), which is transported to the adrenal gland where Cortisol is released. The release of Cortisol activates sympathetic nervous pathways and generates negative feedback to both the hypothalamus and the anterior pituitary (Sherin & Nemeroff, 2011). This negative feedback system appears to be compromised in patients with PTSD, as a lower level Cortisol is observed (Yehuda, Mcfarlane, & Shalev, 1998). The decreased availability of Cortisol results in abnormal regulation of HPA axis, which may promote abnormal stress reactivity and fear processing (Sherin & Nemeroff, 2011).

Neurochemical Factors

The catecholamine family of neurotransmitters, including dopamine (DA) and norepinephrine (NE), has been a central focus of many studies investigating the pathophysiology of PTSD. While researchers are uncertain if the DA metabolism is altered in PTSD, increased urinary secretion of DA and its metabolite was observed in PTSD patients. Mesolimbic DA has been implicated in fear conditioning (Guarraci, Frohardt, & Kapp, 1999). There is evidence in humans that exposure to stressors induces mesolimbic DA release, which in turn could modulate HPA axis responses (Wand, et al., 2007). The increased DA levels in the mesolimbic system may interfere with the fear conditioning process, which may explain the overgeneralization of fear in PTSD. The genetic variation in the DA system is also associated with moderating risk for PTSD (Segman, et al., 2002). NE, on the other hand, is one of the principal mediators of autonomic stress responses.

In the central system, NE and CRH increase fear conditioning and encoding of emotional memories, enhance arousal and vigilance, and integrate endocrine and autonomic responses to stress by interacting with the pathway that connects the amygdala and hypothalamus (Guarraci, Frohardt, & Kapp, 1999). NE is also released from the sympathetic nervous system during stress, which prepares the body for fight-and-flight response. NE hyperactivity is observed in PTSD. This is evidenced by elevations in heart rate, blood pressure, and other psychophysiological measures in patients with PTSD. The decreased binding of platelet α2 receptor, an inhibitor for NE, further suggests NE hyperactivity (Vermetten, & Bremner, 2002). Taken as a whole, NE appears to account for certain classical aspects of PTSD symptomatology, including hyperarousal, heightened startle, and increased encoding of fear memories.

Brain Circuitry

A hallmark feature of PTSD is reduced hippocampal volume. The hippocampus plays a central role in regulating stress hormones and responses through the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. It is involved with the contextual modulation of behaviour, such as fear learning and suppression of fear in safe contexts (Maren, et al., 2013). Hippocampal volume reduction in PTSD may reflect the prolonged exposure to stress and high levels of glucocorticoids (Fuchs, & Gould, 2000). Small hippocampal volumes were associated with the severity of trauma and memory impairments (Stein, et al., 1997). Recent evidence also suggests that decreased hippocampal volumes may be a pre-existing vulnerability factor for developing PTSD (Pitman, et al., 2002).

The amygdala is another subcortical region that likely plays a key role in the pathophysiology of PTSD. The amygdala is involved in emotional processing and is critical for the acquisition of fear responses. Together with the hippocampus, they interact closely with one another for emotional memory and fear conditioning (Phelps, 2004). Although there is no clear evidence for structural alterations of the amygdala in PTSD, functional imaging studies have revealed hyper-responsiveness in PTSD during various behavioural paradigms (Etkin & Wager, 2007). Given that increased amygdala reactivity has been linked to genetic traits that moderate risk for PTSD, increased amygdala reactivity may represent a biological risk factor for developing PTSD (Hariri, et al., 2002).

Treatment and Prevention

Cognitive Processing Therapy

Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) is a 12-week psychotherapy course of treatment consisting of 60-90 minute weekly sessions. At first, an individual will talk about the traumatic event and how these events have affected their life. Next, the trauma is explored at a much deeper level to help think about what happened and determine ways to live with it (WebMD, n.d.). CPT teaches an individual how to evaluate and change their negative thoughts towards their trauma. By changing their thoughts, they can change how they feel.

Prolonged Exposure Therapy

For those who find themselves avoiding any potential reminders of their traumatic event, Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE) will help confront them. This involves 8-15 sessions that are usually 90 minutes in length. At first, the therapist will teach the individual certain breathing techniques to help ease their anxiety when they think about what happened. Once this has been learned, you will construct a list of things you have been avoiding and learn to face them one by one. Lastly, you will recount the experience, go home, and listen to a recording of yourself. This homework will help to ease symptoms (WebMD, n.d.).

Eye Movement Desensitization

With Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR), an individual may not necessarily have to tell the therapist about their experience, but they will concentrate on it as they are doing another task that they enjoy. This way you can associate positive things with your trauma. This takes place over 3 months of weekly sessions (WebMD, n.d.).

Stress Inoculation Training

Stress Inoculation Training (SIT) can be done alone or in a group and is more focused on how to deal with the stress that has arisen from the event. It incorporates massages and breathing techniques to stop negative thoughts through the relaxation of the body. After 3 months of therapy, you will develop the skills needed to deal with the added stresses of life (WebMD, n.d.).

Prevention

The following have been shown to be protective factors for developing PTSD, such that those who diligently practice them will help reduce long-term suffering:

- Continuous communication with important people in your life

- Discussing trauma with loved ones

- Identify as a survivor as opposed to a victim

- Practice the use of positive language and emotion

- Find positive meaning in the trauma

- Help others in their healing process

- Hold the belief that you can manage your feelings and cope (Kissen & Lozano, n.d.).

Medication

The brains of individuals with PTSD process “threats” differently because of imbalances in neurotransmitters. The “fight or flight” response in these individuals is easily triggered which makes them jumpy and on-edge. Medications help to stop thinking and reacting to what happened and help to have a more positive outlook on life. Several drugs can help the brain deal with fear and anxiety. Medications that affect norepinephrine and serotonin levels include: Fluoxetine, Paroxetine, Sertraline, and Venlafaxine (WebMD, n.d.). These drugs have been FDA approved to treat PTSD; however, not everyone’s PTSD is the same and not everyone responds to medication the same. Some off label medications include: antidepressants, MAOIs, SGAs, beta-blockers, benzodiazepines (WebMD, n.d.).

Case Study: War Veteran in the Iraq War

Tom is a 23-year-old, white male who served in the Iraq war for a year (Barlow, 2014). Prior to serving in the military army, Tom had a precursed exposure to trauma. During his adolescence, Tom has witnessed his best friend kill himself by a gunshot in the head. This has caused him to be more vulnerable and preceptive to violence-related trauma. At 21 years of age, Tom witnessed suicide bombers, and many of his fellow soldiers get injured and killed. Without knowing that he would see his fellow soldiers for the last time, he developed intense grief and fear.

Tom describes his most distressing event as having to kill a pregnant woman with a child. He confessed that if he knew he had to kill a pregnant woman, he would have never joined the army. During his interview, Tom states: “I killed an innocent family. The family of someone who loves. I am a murderer.” From this event, Tom has night terrors (which are a more severe form of nightmares), insomnia, anxiety, and flashbacks (i.e. recurring episodes) of the war. He developed a severe drinking problem, in which case he began drinking to suppress his memories.

In 2015, Tom was diagnosed with PTSD. He received Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) for 6 months. Tom also received help from his local community mental health center, where he discovered a new hobby in working with clay and ceramics. This new hobby has immensely helped in controlling his drinking problem and distracting himself from recurrent flashbacks of his trauma. With therapy, Tom has reduced anxiety, guilt, shame and isolation. He experiences increased self-confidence and self-compassion.

Conclusion

In summary, PTSD is a condition that can affect anyone, regardless of age or gender. It can be diagnosed through a questionnaire which analyzes thinking and behaviour after a traumatic event. Symptoms of PTSD are broad and can differ depending on the severity of the PTSD, but they generally interfere with daily activities. Treatments for PTSD are available and include Cognitive Processing Therapy, Prolonged Exposure Therapy, Eye Movement Desensitization, and Stress Inoculation Therapy. Preventative methods exist and should be practiced not just to avoid PTSD itself, but to maintain a healthier and more positive lifestyle. Even with preventative methods, sometimes PTSD is just inevitable depending on the severity of the event, but being able to know your options is essential when such instances occur.

References

6 Common Treatments for PTSD (Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder). (n.d.). Retrieved March 23, 2020, from https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/what-are-treatments-for-posttraumatic-stress-disorder#2

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.).

Barlow, D. (2014). CPT Case Study Example. Clinical Handbook of Psychological Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Broekman, B., Olff, M., & Boer, F. (2007). The genetic background to PTSD. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 31(3), 348–362. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2006.10.001

Crocq, M. A., & Crocq, L. (2000). From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder: a history of psychotraumatology. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 2(1), 47.

Essig, T. (2015). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Is More Than A Bad Story. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/toddessig/2015/12/02/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd-is-more-than-a-bad-story/#3812731a621d

Etkin, A., & Wager, T. D. (2007). Functional Neuroimaging of Anxiety: A Meta-Analysis of Emotional Processing in PTSD, Social Anxiety Disorder, and Specific Phobia. American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(10), 1476–1488. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030504

Friedman, M. J. (2014). PTSD history and overview. United States Department of Veterans Affairs.[Available online].

Fuchs, E., & Gould, E. (2000). In vivo neurogenesis in the adult brain: regulation and functional implications. European Journal of Neuroscience, 12(7), 2211–2214. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00130.x

Guarraci, F. A., Frohardt, R. J., & Kapp, B. S. (1999). Amygdaloid D1 dopamine receptor involvement in Pavlovian fear conditioning. Brain Research, 827(1-2), 28–40. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01291-3

Hariri, A. R., Mattay V. S., Tessitore, A., Kolachana, B., Fera, F., Goldman, D., Egan, M. F., Weinberger, D. R. (2002). Serotonin Transporter Genetic Variation and the Response of the Human Amygdala. Science, 297(5580), 400–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1071829

How to Prevent Trauma from Becoming PTSD | Anxiety and Depression Association of America, ADAA. (n.d.). Retrieved March 23, 2020, from https://adaa.org/learn-from-us/from-the-experts/blog-posts/consumer/how-prevent-trauma-becoming-ptsd

How Traumatic Events Cause PTSD. (n.d.). Verywell Mind. Retrieved March 22, 2020, from https://www.verywellmind.com/ptsd-causes-and-risk-factors-2797397

Khan Academy. (n.d.). What is post traumatic stress disorder? Retrieved March 24, 2020, from https://www.khanacademy.org/science/health-and-medicine/mental-health/anxiety/a/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-article

Lamplugh, M.W. (2017). The Veteran Firefighter and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. Retrieved from https://community.fireengineering.com/profiles/blog/show?id=1219672%3ABlogPost%3A635541

Lewis, L.L. (2018). When PTSD Accompanies a Concussion. Retrieved from https://www.everydayhealth.com/concussion/get-facts-about-concussion-ptsd/

Maren, S., Phan, K. L., & Liberzon, I. (2013). The contextual brain: implications for fear conditioning, extinction and psychopathology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(6), 417–428. doi: 10.1038/nrn3492

National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Retrieved from https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd/index.shtml

Paré, D., Smith, Y., & Paré, J.-F. (1995). Intra-amygdaloid projections of the basolateral and basomedial nuclei in the cat: Phaseolus vulgaris-leucoagglutinin anterograde tracing at the light and electron microscopic level. Neuroscience, 69(2), 567–583. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00272-k

Phelps, E. A. (2004). Human emotion and memory: interactions of the amygdala and hippocampal complex. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 14(2), 198–202. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.03.015

Pitman, R. K., Sanders, K. M., Zusman, R. M., Healy, A. R., Cheema, F., Lasko, N. B., … Orr, S. P. (2002). Pilot study of secondary prevention of posttraumatic stress disorder with propranolol. Biological Psychiatry, 51(2), 189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01279-3

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)—Symptoms and causes. (n.d.). Mayo Clinic. Retrieved March 22, 2020, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355967

Segman, R., Cooper-Kazaz, R., Macciardi, F. et al. Association between the dopamine transporter gene and posttraumatic stress disorder. Mol Psychiatry, 7, 903–907 (2002). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.mp.4001085

Sherin, J. E., & Nemeroff, C. B. (2011). Post-traumatic stress disorder: the neurobiological impact of psychological trauma. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 13(3), 263–278.

Skelton, K., Ressler, K. J., Norrholm, S. D., Jovanovic, T., & Bradley-Davino, B. (2012). PTSD and gene variants: New pathways and new thinking. Neuropharmacology, 62(2), 628–637. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.02.013

Stein, M. B., Koverola, C., Hanna, C., Torchia, M. G., & Mcclarty, B. (1997). Hippocampal volume in women victimized by childhood sexual abuse. Psychological Medicine, 27(4), 951–959. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005242

Tan, G., Dao, T. K., Farmer, L., Sutherland, R. J., & Gevirtz, R. (2011). Heart rate variability (HRV) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a pilot study. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, 36(1), 27-35.

The Veteran Firefighter and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder – Fire Engineering Training Community. (n.d.). Retrieved March 24, 2020, from https://community.fireengineering.com/m/blogpost?id=1219672%3ABlogPost%3A635541

Tull, M. (2019). Symptoms and Diagnosis of PTSD. Verywell Mind. Retrieved from https://www.verywellmind.com/requirements-for-ptsd-diagnosis-2797637

Tull, M. (2020). What Is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)? Verywell Mind. Retrieved March 25, 2020, from https://www.verywellmind.com/an-overview-of-ptsd-2797638

Vermetten, E., & Bremner, J. D. (2002). Circuits and systems in stress. II. Applications to neurobiology and treatment in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 16(1), 14–38. doi: 10.1002/da.10017

Wand, G. S., Oswald, L. M., Mccaul, M. E., Wong, D. F., Johnson, E., Zhou, Y., … Kumar, A. (2007). Association of Amphetamine-Induced Striatal Dopamine Release and Cortisol Responses to Psychological Stress. Neuropsychopharmacology, 32(11), 2310–2320. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301373

Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The PTSD checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5).

Yehuda, R., Mcfarlane, A., & Shalev, A. (1998). Predicting the development of posttraumatic stress disorder from the acute response to a traumatic event. Biological Psychiatry, 44(12), 1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00276-5