Table of Contents

Plaque Psoriasis

Presentation 3: Plaque Psoriasis Powerpoint File

Introduction

<style justify></style> Psoriasis is a chronic, autoimmune disease of the skin and joints (Langley et al., 2005). Robert Willan, the father of modern dermatology, is credited with the first detailed clinical description of psoriasis, and hence, it is also termed as Willan'slepra (Dogra & Mahajan, 2016). Although there are five main types of of psoriasis, plaque psoriasis is the most common type, accounting for 90% of all cases (Mak et al., 2010).

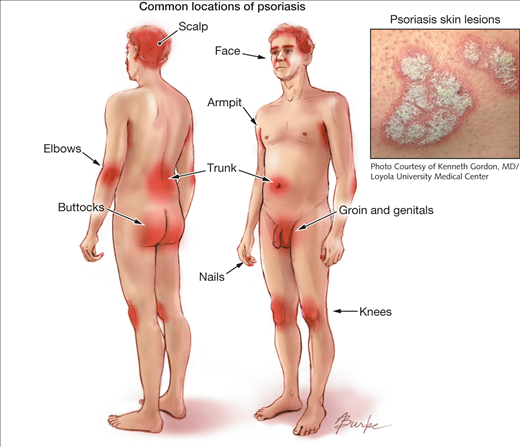

Plaque psoriasis is predominantly characterized by abnormal red, silver and scaly skin patches covering the body (Dogra & Mahajan, 2016). While the pathogenesis is unclear, plaque psoriasis is attributed to a T-cell mediated hyper proliferation of keratinocyte (Gudjonsson et al., 2004). The skin patches typically appear on the scalp, back, trunk, elbows, knees, and genital areas but can also affect any other areas of the body. Distribution and severity of plaques on the body is random, and vary greatly from patient to patient from large coverage of the body in lesions to localized plaques no larger than a dime. The stigmatizing visible markings of this condition can have a significant negative impact on the physical, emotional, and, psychosocial wellbeing of affected patients (Langley et al., 2005).

Figure 1: Plaque psoriasis

Image from: http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1104805 </style>

Psoriasis is found worldwide but the prevalence varies among different ethnic groups (Dogra & Mahajan, 2016). While men and women are afflicted with equal frequency, plaque psoriasis is more common in adults then children. It also has a strong genetic predisposition but environmental factors such as infections can play an important role in the presentation of disease (Langley et al., 2005).

Currently, there is no cure for psoriasis and treatment is largely symptomatic and vary according to the severity of the disease. Earlier treatments have included application of emollients or keratolytic agents to hydrate the skin or shed off the skin (Raut et al., 2013). Later treatments, such as topical agents have been modified to treat the underlying T-cell proliferation. Systemic treatments including methotrexate, cyclosporine, acitretin, as well as light therapy are prominent for severe psoriasis(Raut et al., 2013). A combination of these therapies have provided effective and rapid modalities to suppress the disease and reduce the toxic side effects of treatment.

<br>

Epidemiology

<style justify></style> The worldwide prevalence of psoriasis is estimated to be approximately 2–3% (Dogra & Mahajan, 2016). The disease is known to have higher prevalence in the polar regions of the world attributed to differences in sunlight exposure (Dogra & Mahajan, 2016). While psoriasis is found worldwide, the prevalence varies among different ethnic groups. It appears to be low in certain ethnic groups such as the Japanese, and may be absent in aboriginal Australians and Indians from South America (Langley et al., 2005). It is also reported to occur with similar frequency in both males and females. While psoriasis can onset at any age, the disease is less common in children than adults. The prevalence of psoriasis in adults ranged from 0.91 to 8.5 percent, and the prevalence of the disease in children ranged from 0 to 2.1 percent (Parisi et al., 2013). Plaque psoriasis appears to have a biomedical age of onset, occurring either between the ages of 15 and 20 years and or the ages of 50 and 69 years (Parisi et al., 2013).

<br>

Signs and Symptoms

Figure 2: A typical psoriatic plaque

Image from: http://www.wikipedia.com

Figure 3: A red and scaly scalp lesion

Image from: http://nopsoriasis.net </style>

<style justify> Common Symptoms

Plaque psoriasis is characterized by a few main symptoms. First and foremost are the plaques, or skin lesions, themselves. These lesions are often red or silvery in colour, inflamed, scaly or dry, and generally sore or itchy (WebMD, 2017). Plaques are hyperproliferated skin cells on the epidermal layer, and is attributed to premature maturation of keratinocytes and dermal inflammatory cells. These comprise of dendritic cells, macrophages and T cells (Palfreeman et al., 2013). These skin cells with reproduce very quickly, and build up, eventually shedding in scales and patches. These patches are the most visible and obvious symptom of psoriasis, regardless of the type. Psoriasis sufferers are also afflicted by skin soreness, itchiness, and can even report a sensation of burning in the affected areas. For plaque psoriasis sufferers, approximately 50% may also experience scalp plaques (Healthline, 2017). These are similar in look to the bodily plaques.

The location of plaques will change as the affected lesions begin to heal (Healthline, 2017). Newer patches may appear in different locations during future bouts. The symptoms of plaque psoriasis affect every sufferer differently, and no two people will experience exactly the same symptoms and plaque physiology.

The ‘Plaque’ in Plaque Psoriasis

The characteristic skin lesions of psoriasis take the form of raised plaques with silvery scales that can present on any part of the skin. The lesions usually begin as erythematous papules, and then tend to extend peripherally, eventually coalescing to form plaques (Raychaudhuri et al., 2014). However, in plaque psoriasis, the most common areas of the body that are afflicted are the scalp, back, and the extensor surfaces like knees and elbows (Palfreeman et al., 2013). Distribution of plaques on the body is generally random, and it varies greatly from patient to patient. Some may experience large coverage of the body in lesions, some may experiences plaques no larger than a dime.

New lesions can form at random, but also occur when the skin receives direct cutaneous trauma, and this is known as the Koebner phenomenon. Plaque psoriasis sufferers also experience the Auspitz phenomenon, where pinpoint bleeding occurs following a mild disruption of the superficial layer of the lesion. Plaque psoriasis is a chronic disorder, and reappearance of lesions do not necessarily occur in the same spots every time. Also, unlike inverse psoriasis, plaque psoriasis also does not afflict the genitals or armpits. </style>

<br>

Diagnosis

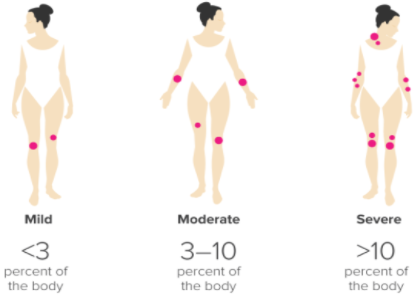

Figure 4: Ranking the severity of psoriasis, via PASI

Image from: http://www.healthline.com </style>

<style justify> Currently, there is no set diagnostic criteria for psoriasis, and so diagnosis is made clinically through pattern recognition and a detailed morphologic evaluation of skin lesions. Based on the morphology of the lesions and locations of plaques, psoriasis has been classified into various clinical phenotypes (Raychaudhuri et al., 2014).

In this way, the simplest and most accurate way to get an accurate diagnosis of psoriasis is simply to go to the dermatologist and have the doctor assess the lesions on the affected skin. More often than not, dermatologists are very well versed in the symptomatic characteristics of psoriasis and can quickly give a visual diagnosis without the need for blood sampling or extensive testing (WebMD, 2017).

A frequent issue with visual diagnosis of psoriasis is that physiologically, this condition is very similar in look to the presentation of eczema. Patches of plaque psoriasis and eczema share the characteristics of redness, scaliness, and inflammation, making them hard to distinguish from one another (WebMD, 2017). However, psoriasis is usually also accompanied by silvery scaling as well as red. This is because psoriasis is a chronic autoimmune condition that results in the overproduction of skin cells and these dead cells build up into silvery-white scales. Eczema is typically not covered in this dead skin, as it inflammation, and not an immune compromised skin disorder. This is one key feature that can distinguish the two. Yet, sometimes psoriasis does not produce this silvery covering and can still be hard to distinguish from eczema.

When cases like this are more difficult, a skin biopsy can also be used to give a more accurate diagnosis (WebMD, 2017). In a skin biopsy, a small sample of affected skin is taken from a patient and observed under the microscope. The dermatologist will look for clubbed epidermal projections or epidermal thickening as characteristics of psoriasis lesions (Raychaudhuri et al., 2014). This technique can be used when a diagnosis is more difficult, like in the comparison to eczema, or in atypical cases (Healthline, 2017).

The clinical phenotypes of psoriasis have been classified based on factors such as age of onset, degree of skin involvement, morphologic pattern and predominant involvement of specific anatomic location of the body (Raychaudhuri et al., 2014).

Dermatologists can also rank the severity of the condition based on the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index, or PASI. This scale allows the doctor to rank the severity of the condition based on how much surface area of the skin is covered in lesions (Healthline, 2017). Less than 3% boyd coverage of plaques is considered ‘mild’, 3-10% is ‘moderate’, and anything over 10% is considered ‘severe’. This is largely at the discretion of the physician. The assessment is made by assigning an ascending score to plaque severity in terms of thickness, redness, and scaling, and the extent of the plaque spread (Healthline, 2017). </style>

<br>

Etiology

<style justify>The etiology of this disease is unclear, as there is no definite cause. This is considered to be a multifactorial disease, which means that it is caused by a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

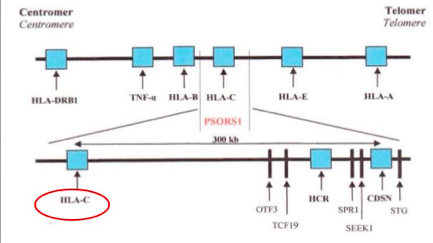

The idea of psoriasis having a genetic basis has been accepted in the medical community for many years now. However, not all the genes that are associated with this disease have yet been identified, through the general region of these genes is known (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007). Specifically, one locus that has been identified in psoriasis is the class 1 region of the major histocompatibility locus antigen cluster (MHC). There have been nine loci identified on different chromosomes that are associated with this disease, and they are named psoriasis susceptibility 1 through 9 (PSOR1 through PSOR9). These genes are located on pathways that lead to inflammation, and mutations of these genes lead to psoriasis (Nestle, Kaplan, & Barker, 2009). The most significant gene locus is PSORS-1, which is located on chromosome 6p2 in the MHC, though the specific gene has not yet been identified. This gene locus contains genes such as the HLA-C variant HLA-Cw6. This locus accounts for 35%-50% of the heritability of this disease (Smith & Barker, 2006). Interestingly, these loci are shared by other autoimmune and inflammatory diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease, type1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and atopic dermatitis, which indicates that these complex inflammatory diseases have a similar root cause (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007). The MHC has a low penetrance of only about 10%; this suggests that other factors should also be considered in the etiology of this disease (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007). Another set of genes that have the ability to affect the immune system are those that are involved with keratinocyte differentiation. Specifically, variants in the SLC9A3R1/NAT9 region and loss of the RUNX binding site are factors that could affect regulation of the immune synapse (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007). Another gene pool to be considered is alleles that encode IL-12, IL-19/20, and IRF2, as these also play a role in the pathophysiology of psoriasis (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007).

Figure 5: The genetic linkage of plaque psoriasis

Image from: https://www.slideshare.net/Gurpgork/psoriasis-35245580

There are also environmental factors at play which contribute to this disease. These include prolonged psychological stress and trauma and infections in the body (Smith & Barker, 2006). Another environmental trigger is changes in the climate (Smith & Barker, 2006). Certain medications and drugs may also induce psoriasis. Specifically, drug-induced psoriasis may occur with the use of medications such as beta blockers, lithium, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (Jain, 2012) and TNF inhibitors (Guerra & Gisbert, 2013).

</style>

<br>

Pathophysiology

<style justify>

In people who have this condition, skin cells proliferate much faster than normal (Raychaudhuri, Maverakis & Raychaudhuri, 2014). Specifically, skin cells are replaced 3-5 days in those who have the condition, as opposed to the regular cycle of 28-30 days (Parrish, 2012). In those that have psoriasis, their immunological functioning is an amplification of the immune activity that takes place in regular skin cells.

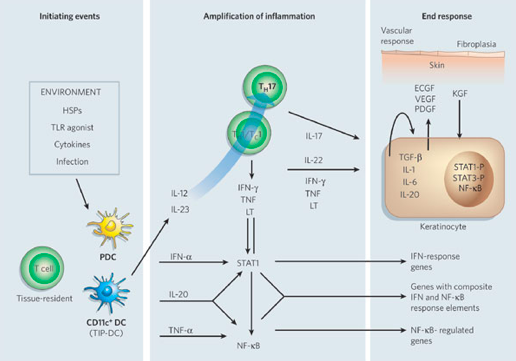

The dendritic cell is an antigen-presenting cell, and it is activated by the presence of a foreign substance in the cell. The nature of this autoimmune diseases causes the body to recognize its own cells as foreign. Upon detecting an antigen, the dendritic cell travels to the lymph node and presents the antigen to the naive T-cell using co-stimulatory signals. Dendritic cells function to bridge the innate immune system and adaptive immune system, and are increased in psoriatic lesions (Ouyang, 2010). Activated dendritic cells contribute cytokines including IFN-, IL-20, IL-12 and IL-23, which in turn activates the naïve T-cell (Lowes, Bowcock & Krueger, 2007). The T-cells migrate from the dermis to the epidermis. Following extravasation into the skin, T-cell-derived proinflammatory cytokines are synthesized and secreted; such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin-1β, interleukin-6, interleukin-36 and interleukin-22 (Nestle, Kaplan, & Barker, 2009). When these cytokines bind to their receptors, intracellular protein cascades are activated, which ultimately leads to keratinocyte hyperproliferation and the formation of psoriatic plaque (Nestle, Kaplan, & Barker, 2009). Specifically, IL-36γ is believed to be the biomarker that is unique in the development of psoriasis as opposed to other inflammatory skin diseases. Phosphorylation of specific cell surface biomarker activates another family of signalling proteins: STAT proteins. The STAT proteins, once activated, dimerize and translocate to the cell nucleus where they regulate the genes that are responsible for the differentiation and migration of immune cells that are involved in psoriasis. There occurs a downstream activation of numerous IFN-responsive genes through signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) (Lew, Bowcock & Krueger, 2004). The key cytokines that can activate STAT or NF-B transcription factors (which are involved in amplifying inflammation) include TNFs, lymphotoxin (LT), IL-1, IL-17, IL-20, IL-22 and IFNs. Interleukin-22 works to induce keratinocytes to secrete neutrophil-attracting cytokines (Lew, Bowcock & Krueger, 2004). In response to these chemical messages from T-cells, keratinocytes also secrete proinflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α. These cytokines signal the activation of downstream inflammatory cells, which arrive to the site and stimulate additional inflammation (Nestle, Kaplan, & Barker, 2009). The hyper activation of the keratinocytes is maintained through molecules such as TGF-, IL-1, IL-6 and IL-20, which may act as keratinocyte autocrine and paracrine growth factors (Lew, Bowcock & Krueger, 2004). This creates an ongoing process of cell activation and immune responses, ultimately resulting in an accumulation of epidermal and immune cells, which leads to a thickened and inflamed epidermis.

Figure 6: Cytokine networks in psoriasis

Image from: http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v445/n7130/abs/nature05663.html </style>

<br>

Prognosis

<style justify>

Psoriasis is, unfortunately, an incurable disease. Treatment and management options mainly exist to enhance the patient’s sense of well-being and independence (Menter et al., 2008). Although most sufferers of psoriasis do not experience any more than mild skin lesions, which are easily treatable with the use of topical therapies, some patients have a more severe form of the disease which can have a significantly negative impact on their quality of life (Menter et al., 2008). Depending on the location and severity of outbreaks, caring for, and performing basic functions, like sleeping and self-care, can become highly difficult. Plaques on certain locations, like the face and scalp, can also be particularly embarrassing for the patient and may cause individuals to isolate themselves from social activities (Menter et al., 2008). Individuals with this disease may also feel particularly self-conscious about their appearance, which could lead to a lower self-esteem and may cause depression. Some of the younger patients may also experience bullying, as a result of their condition; these factors lead to a high rate of suicide contemplation (Menter et al., 2008). However, these concerns can be mitigated if the patients seek help earlier on. Various traditional and alternative therapeutic practices exist to reduce the appearance or onset of plaques on the skin, that may allow the patient to develop a healthy self-image (Menter et al., 2008). Most of these treatment and management strategies exist only to make the patient more comfortable, physically and psychologically. </style>

<br>

Treatment and Management

<style justify>

TREATMENT

Treatment options are chosen that are appropriate to the severity of the condition. Mild, localized psoriasis is treated with topical therapy while more extensive, severe disease will require systemic, expensive, and potentially hazardous treatment.

Topical agents

There are several topical treatment agents available for short-term relief of this disease. The most common ones are available both over-the-counter (OTC) and by prescription, depending on the degree of severity (Mason et al., 2009). The first line of effective treatments includes topical steroid cream and dithranol. Alternatively, coal tars and keratolytic treatments, such as salicylic acid, can be employed by patients (Mason et al., 2009). These are available OTC and can be found in a variety of forms such as, shampoos (best for scalp psoriasis), creams, lotions, and ointments (Mason et al., 2009). In some cases, physicians prescribe vitamin D analogs, which act on vitamin D receptors on the skin to reduce the appearance of plaques (Wolters, 2005). Although coal tars, keratolytics, and vitamin D analogues are sometimes effective, some research suggests that they may be no better than placebos in the treatment of localized lesions (Mason et al., 2009).

Topical Corticosteroids

As mentioned in pathophysiology, psoriasis is an autoinflammatory disease, actively involving keratinocytes and leukocytes in the immunopathology of the disease (Uva et al., 2012). Topical corticosteroids mainly interact with the glucocorticoid receptor and initiate a series of signal transduction pathways both intracellularly and extracellularly (Uva et al., 2012). Glucocorticoids possess numerous functions such as anti-inflammatory, antimitotic, apoptotic, vasoconstrictive and immunomodulatory functions (Uva et al., 2012). These properties are closely associated with their efficacy in the skin disease treatment. The main function in the treatment of psoriasis is to reduce inflammation and modulate the activity of immune responders. This is mainly done by altering transcription of respective genes involved in anti-inflammatory, inflammatory, and immunomodulatory activity (Uva et al., 2012).

Dithranol

Corticosteroids are effective when they are employed for short-term flares, but with worsening, chronic flares, dithranol is deemed more effective. Dithranol works to slow the growth of abnormal skin cells, which is why it is better for chronic and prolonged relief (Kemeny et al., 1990). The drug inhibits keratinocyte hyperproliferation, granulocyte function, and, in addition, may exert an immunosuppressive effect (Kemeny et al., 1990).

This is supported by the results of a systemic analysis conducted by Lowe et al., which compared psoriasis improvement rates in patients treated with either dithranol or a corticosteroid. The researchers concluded that corticosteroids are most effective when used for short-term flares, and dithralin was best used for chronic treatment of the disease (Lowe et al., 1984).

Systemic Agents

Systemic agents are prescription drugs that affect the entire body. Most patients prescribed these agents will have moderate to severe psoriasis and/or psoriatic arthritis. Systemic medications are also used by those who are not responsive to or are unable to use topical medications or ultraviolet (UV) light treatment (Feldman, 2013).

These drugs are taken by mouth in liquid or pill form or given by injection into the skin or muscle or through intravenous (IV) infusion (Feldman, 2013).

Methotrexate

This drug is in a class of medications known as antimetabolites and is typically only used in moderate to severe cases of psoriasis (Feldman, 2013). Its mechanism of action involves immunosuppression, in which T-cells are deactivated in order to decrease the autoimmune response to epidermal cells (Felman, 2013). It is usually taken orally, either in pill or liquid form, but can be taken via IV (Mayo Clinic, 2015). There are risks surrounding long-term use of methotrexate, including severe liver damage or the decreased production of white and red blood cells or blood platelets (Mayo Clinic, 2015).

Cyclosporine

This drug is used for adults with severe psoriasis and otherwise normal immune systems. It suppresses the activity of T-cells within the immune system, which slows the growth of skin cells (Feldman, 2013). Cyclosporine is typically taken orally in 3 to 5 mg/kg per day with symptom relief within 4 weeks (Feldman, 2013). Since this drug is suppressing your immune system, this increases the patient’s chances of infection or related health problems. There are risks with taking the medication in high doses or for long-term use and these include, high blood pressure or kidney ailments (Mayo Clinic, 2015).

Soriatane (acitretin)

This drug is an oral retinoid, which is a synthetic form of vitamin A and usually prescribed to those with severe cases of psoriasis (Feldman, 2013). Retinoids help control the multiplication of cells, including the speed with which skin cells grow and shed, which increases in psoriasis (Mayo Clinic, 2015). The dose ranges of acitretin can be anywhere from 25 mg every other day to 50 mg daily (Feldman, 2013). Acitretin can also be prescribed in combination with UVA or PUVA therapy; shown to increase response rates (Feldman, 2013). The use of this medication may put one at risk of lip inflammation or hair loss. Those who are or may become pregnant should also be wary of this medication as it has been shown to elicit birth defects in pregnant women (Mayo Clinic, 2015).

MANAGEMENT

Moisturizers and emollients

Emollients, moisturizers, and keratolytic agents are types of topical agents for the treatment of psoriasis. These can be used instead of, or in conjunction with classic pharmaceutical treatments to help reduce the appearance of plaques. Moisturizers are highly beneficial in normalizing the hyperproliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis of pathological keratinocytes (Fluhr et al., 2008). They also exert anti-inflammatory effects through lipids found in the moisturizer itself. Hydration of the dry surface layer of these plaques allows for repair of the barrier and improved barrier function, along with making the epidermis more resistant to external stressors (Fluhr et al., 2008). Keratolytic agents, such as salicylic acid, are beneficial when used in the initial phase of plaque formation, because it allows loosening and shedding of dead skin layers (Fluhr et al., 2008). Moisturizers and emollients, which are lipid-rich, are best used in the intermediate and chronic phase of the disease, since they allow hydration of dry skin layers and increase the water binding ability of the skin (Fluhr et al., 2008). These can also be combined with the use of bath oils, which is also another strategy patients can employ (Fluhr et al., 2008).

Balneotherapy

This type of therapy is used to treat disease by bathing in mineral springs or mineralized, treated, warm water. Some spas offer this type of treatment and it has shown to be particularly beneficial in the treatment of psoriasis. The emergence of this type of treatment dates back to the 1800s and was initially scoffed at by the scientific community but recent scientific evidence is emerging to support this type of treatment (Peroni et al., 2008). Although balneotherapy is practiced with a variety of mineral springs and muds, that are considerably different in hydrogeological origin, temperature, and chemical composition, the most common type used for the treatment of psoriasis is employed by bathing in the Dead Sea (Peroni et al., 2008). Since this is not readily available anywhere outside of Jordan, Israel, and Palestine, many spas utilize treatment methods that closely mimic the composition of the Dead Sea waters. A more effective, albeit costly, form of this type of therapy combines phototherapy and balneotherapy (photobalneotherapy) (Peroni et al., 2008). In a study conducted by Peroni et al., researchers evaluated the safety and efficacy of balneotherapy compared with photobalneotherapy in the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis. The results demonstrate that even 1 week of balneotherapy and photobalneotherapy was sufficient to obtain statistically significant improvements in the PASI score (Peroni et al., 2008). Two weeks of this type of therapy induced an even greater effect in the reduction of psoriatic plaques, but in this case, photobalneotherapy was marginally more effective than balneotherapy alone (Peroni et al., 2008). Although these treatments provide a safe and effective way to reduce the appearance of plaques, they demonstrate only short-term effects (Peroni et al., 2008). When researchers followed up with these participants a few weeks after the cessation of treatment, they found that the plaques were slowly forming again, however, the treatment seemed to reduce the severity and size of plaque formation (Peroni et al., 2008). In this case, photobalneotherapy provided a more protective effect than balneotherapy alone (Peroni et al., 2008). Therefore, balneotherapy appears to be an interesting adjuvant or alternative therapy for patients with chronic plaque psoriasis, and can thus be offered to patients willing to discontinue momentarily pharmacologic therapy (Peroni et al., 2008).

Mechanism: Balneotherapy with sulphurous medicinal waters is known as an effective treatment in psoriasis, but there is no exact explanation for its mode of action (Boros et al., 2013). However, studies speculate that it may be linked to an increase in serum levels of anti-inflammatory neuropeptides (Boros et al., 2013).

Phototherapy

Dermatological practices of phototherapy subject patients to ultraviolet radiation in order to treat certain skin diseases. In Ancient Egyptian and Indian times, sunlight, and a plant-based extract known as psoralens, were used to treat some of the more common skin conditions, like vitiligo (Matz, 2010). Now, this type of combination is known as Psoralens and UVA therapy (PUVA) (Matz, 2010). In the past 30 years, phototherapy has cracked its way into modern medicine. Although there were some skepticisms from physicians and researchers, this type of therapy is best used in conjunction with other pharmacological or complementary and alternative treatments (Matz, 2010).

Ultraviolet light has three categories: UVA, UVB, and UVC. Although phototherapy is most often used to treat psoriasis vulgaris, some forms of phototherapy, such as PUVA and UVB therapy, are effective in almost all forms of the disease (Matz, 2010). UVB therapy, which provides high doses of UVB rays, is more widely accepted because it does not require oral medication and can be used in more severe cases, or cases of pregnancy and lactation (Matz, 2010). Patients that are younger or have comorbidities with other skin diseases should avoid subjection to UV radiation, to avoid risk of malignant skin cancers (Matz, 2010).

Diet

Diet has been suggested to play a role in the aetiology and pathogenesis of psoriasis. Fasting periods, low energy diets and vegetarian diets improved psoriasis symptoms in some studies (Wolters, 2005). Most commonly, diets rich in n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids from fish oil showed beneficial effects. All these diets modify the polyunsaturated fatty acid metabolism so that inflammatory processes are suppressed (Wolters, 2005).

</style>

<br>

Future Studies

<style justify>

Some studies demonstrate that patients who suffer from chronic psoriasis also have more insulin resistant profiles than healthy adults (Ucak et al., 2006). They are also more likely to develop insulin resistance (Ucak et al., 2006). The mechanism of this particular phenomenon is mostly unknown, however, future studies are being conducted to test the underlying mechanisms of action.

</style>

<br>

References

Boros, M., Kemény, Á., Sebők, B., Bagoly, T., Perkecz, A., Petőházi, Z., … & Helyes, Z. (2013). Sulphurous medicinal waters increase somatostatin release: it is a possible mechanism of anti-inflammatory effect of balneotherapy in psoriasis. European Journal of Integrative Medicine, 5(2), 109-118.

Burke, A. (2017). Plaque Psoriasis. Retrieved from http://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/1104805

Dogra, S., & Mahajan, R. (2016). Psoriasis: Epidemiology, clinical features, co-morbidities, and clinical scoring. Indian Dermatology Online Journal, 7(6), 471.

Feldman, S. R., Pearce, D. J., Dellavalle, R. P., & Duffin, K. C. (2013). Treatment of psoriasis. UpToDate. http://www.uptodate.com (accessed April, 2017).

Fluhr, J. W., Cavallotti, C., & Berardesca, E. (2008). Emollients, moisturizers, and keratolytic agents in psoriasis. Clinics in dermatology, 26(4), 380-386.

Gudjonsson, J. E., Johnston, A., Sigmundsdottir, H., & Valdimarsson, H. (2004). Immunopathogenic mechanisms in psoriasis. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 135(1), 1-8.

Guerra, I., & Gisbert, J. P. (2013). Onset of psoriasis in patients with inflammatory bowel disease treated with anti-TNF agents. Expert review of gastroenterology & hepatology, 7(1), 41-48.

Jain, S. (2012). Dermatology: illustrated study guide and comprehensive board review. Springer Science & Business Media.

Kemeny, L., Ruzicka, T., & Braun-Falco, O. (1990). Dithranol: a review of the mechanism of action in the treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Skin Pharmacology and Physiology, 3(1), 1-20.

Langley, R. G., Krueger, G. G., & Griffiths, C. E. M. (2005). Psoriasis: epidemiology, clinical features, and quality of life. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 64(suppl 2), ii18-ii23.

Lew, W., Bowcock, A. M., & Krueger, J. G. (2004). Psoriasis vulgaris: cutaneous lymphoid tissue supports T-cell activation and ‘Type 1’inflammatory gene expression. Trends in immunology, 25(6), 295-305.

Lowe, N. J., Ashton, R. E., Koudsi, H., Verschoore, M., & Schaefer, H. (1984). Anthralin for psoriasis: Short-contact anthralin therapy compared with topical steroid and conventional anthralin. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 10(1), 69-72.

Lowes, M. A., Bowcock, A. M., & Krueger, J. G. (2007). Pathogenesis and therapy of psoriasis. Nature, 445(7130), 866-873.

Mak, R. K. H., Hundhausen, C., & Nestle, F. O. (2009). Progress in understanding the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Actas dermo-sifiliograficas, 100, 2-13.

Mason, A. R., Mason, J., Cork, M., Dooley, G., & Edwards, G. (2009). Topical treatments for chronic plaque psoriasis. The Cochrane Library.

Matz, H. (2010). Phototherapy for psoriasis: what to choose and how to use: facts and controversies. Clinics in dermatology, 28(1), 73-80.

Menter, A., Gottlieb, A., Feldman, S. R., Van Voorhees, A. S., Leonardi, C. L., Gordon, K. B., … & Beutner, K. R. (2008). Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 58(5), 826-850.

Nestle, F., Kaplan, D., & Barker, J. (2009). Psoriasis. New England Journal Of Medicine, 361(5), 496-509. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/nejmra0804595

Ouyang, W. (2010). Distinct roles of IL-22 in human psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease. Cytokine & growth factor reviews, 21(6), 435-441.

Palfreeman, A. C., McNamee, K. E., & McCann, F. E. (2013). New developments in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: a focus on apremilast. Drug Des Devel Ther, 7, 201-210.

Parisi, R., Symmons, D. P., Griffiths, C. E., & Ashcroft, D. M. (2013). Global epidemiology of psoriasis: a systematic review of incidence and prevalence. Journal of Investigative Dermatology, 133(2), 377-385.

Parrish, L. (2012). Psoriasis: symptoms, treatments and its impact on quality of life. British journal of community nursing, 17(11), 524-528.

Peroni, A., Gisondi, P., Zanoni, M., & Girolomoni, G. (2008). Balneotherapy for chronic plaque psoriasis at Comano spa in Trentino, Italy. Dermatologic therapy, 21(s1), S31-S38.

“Plaque Psoriasis Pictures”. Healthline. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

“Psoriasis Symptoms and Triggers”. WebMD. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

Psoriasis: Treatment and Drugs. (2015). Mayo Clinic. http://www.mayoclinic.org (accessed April, 2017).

Raychaudhuri, S. K., Maverakis, E., & Raychaudhuri, S. P. (2014). Diagnosis and classification of psoriasis. Autoimmunity reviews, 13(4), 490-495.

Raut, A. S., Prabhu, R. H., & Patravale, V. B. (2013). Psoriasis clinical implications and treatment: a review. Critical Reviews™ in Therapeutic Drug Carrier Systems, 30(3).

Smith, C. H., & Barker, J. N. W. N. (2006). Psoriasis and its management. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 333(7564), 380.

Ucak, S., Ekmekci, T. R., Basat, O., Koslu, A., & Altuntas, Y. (2006). Comparison of various insulin sensivity indices in psoriatic patients and their relationship with type of psoriasis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology, 20(5), 517-522.

Uva, L., Miguel, D., Pinheiro, C., Antunes, J., Cruz, D., Ferreira, J., & Filipe, P. (2012). Mechanisms of action of topical corticosteroids in psoriasis. International journal of endocrinology, 2012.

Wolters, M. (2005). Diet and psoriasis: experimental data and clinical evidence. British Journal of Dermatology, 153(4), 706-714.

<br>