Table of Contents

What is Chagas Disease?

Chagas disease is named after the Brazilian physician Carlos Chagas, who discovered the disease in 1909. It is caused by the parasite Trypanosoma cruzi, which is transmitted to animals and people by insect vectors and is found only in the Americas (mainly, in rural areas of Latin America where poverty is widespread). Chagas disease (T. cruzi infection) is also referred to as American trypanosomiasis.American trypanosomiasis, Chagas disease can infect anyone, but is diagnosed most often in children. Left untreated, Chagas disease later can cause serious heart and digestive problems (Buckner, Wilson, White, & Voorhis, 1998).

Distribution

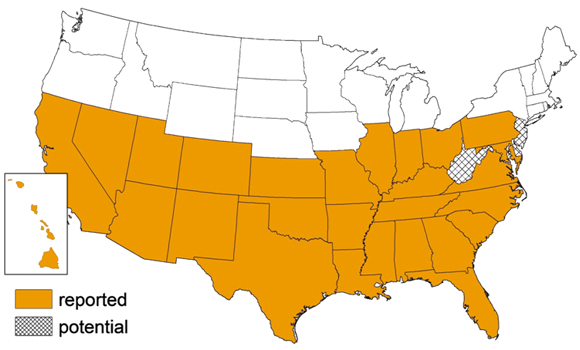

People who have Chagas disease can be found anywhere in the world. However, vectorborne transmission is confined to the Americas, principally rural areas in parts of Mexico, Central America, and South America. In some regions of Latin America, vector-control programs have succeeded in stopping this type of disease spread. Vectorborne transmission does not occur in the Caribbean (for example, in Puerto Rico or Cuba). Rare vectorborne cases of Chagas disease have been noted in the southern United States(Hall & Wilkinson, 2012). Infection can also be acquired through blood transfusion, congenital transmission (from infected mother to child) and organ donation, although these are less frequent.

Figure:The habitat of potential vectors is increasing.KU and NJ are projected to become suitable habitats within the next five years

Transmission

In Latin America, T. cruzi parasites are mainly transmitted by contact with the faeces of infected blood-sucking triatomine bugs. These bugs, vectors that carry the parasites, typically live in the cracks of poorly-constructed homes in rural or suburban areas. Normally they hide during the day and become active at night when they feed on human blood(Buckner, Wilson, White, & Voorhis, 1998). They usually bite an exposed area of skin such as the face, and the bug defecates close to the bite. The parasites enter the body when the person instinctively smears the bug faeces into the bite, the eyes, the mouth, or into any skin break(Hall & Wilkinson, 2012).

T. cruzi can also be transmitted by:

- Consumption of food contaminated with T. cruzi through for example the contact with infected triatomine bug faeces

- Blood transfusions (blood from infected donors)

- Passage from an infected mother to her newborn during pregnancy or childbirth

- Organ transplants using organs from infected donors

- Laboratory accidents

Symptoms

Chagas disease can cause a sudden, brief illness, or it may be a long-lasting condition. Symptoms range from mild to severe, although many people don't experience symptoms until the chronic stage.

Acute phase

The acute phase of Chagas disease, which lasts for weeks or months, is often symptom-free. When signs and symptoms do occur, they are usually mild and may include:

- Swelling at the infection site

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Rashes on the body

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea, diarrhea or vomiting

- Swollen glands

- Enlargement of your liver or spleen

Signs and symptoms that develop during the acute phase usually go away on their own. If left untreated, the infection persists and, in some cases, advances to the chronic phase.

Chronic phase

Signs and symptoms of the chronic phase of Chagas disease may occur 10 to 20 years after initial infection, or they may never occur. In severe cases, however, Chagas disease signs and symptoms may include:

- Irregular heartbeat

- Congestive heart failure

- Sudden cardiac arrest

- Difficulty swallowing due to enlarged esophagus

- Abdominal pain or constipation due to enlarged colon

Diagnosis

T. Cruzi parasite

Trypansoma cruzi parasite in a thin blood smear.

The diagnosis of Chagas disease can be made by observation of the parasite in a blood smear by microscopic examination. A thick and thin blood smear are made and stained for visualization of parasites. However, a blood smear works well only in the acute phase of infection when parasites are seen circulating in blood. Diagnosis of chronic Chagas disease is made after consideration of the patient's clinical findings, as well as by the likelihood of being infected, such as having lived in an endemic country. Diagnosis is generally made by testing with at least two different serologic tests

Pathophysiology

The foremost explanation for Chagas heart disease pathogenesis is the persisting presence of the T. cruzi parasite in the body, which creates altered autoimmune mechanisms. Reports have shown an increased number of antibodies present in Chagas disease patients that act against receptors on cardiomyocytes, interfering with cardiac activity (Higuchi et al., 2003). It has also been shown that T. cruzi infection causes the appearance of lymphocytes that are cytotoxic against myocardial fibers, leading to cardiac inflammation (Higuchi et al., 2003). Another way that the parasite acts on the heart is to induce dilation in the microvasculature of the heart through vasodilator substances, which causes fibrotic lesions in various areas of the heart (Higuchi et al., 2003). The increased lymphocyte and antibody activity combines with increased expression of inflammatory cytokines and adhesion molecules that help antibodies and lymphocytes adhere to target cardiac cells; this in addition to the microvascular changes are what leads to the characteristic and potentially fatal heart lesions found in Chagas disease patients.

Figure: A-shows the enlargement of the Esophagus after the infection, B/C/D- show the enlargement of the cardiac muscle outwards.Persistent parasitemia can lead to autoimmunity, Epitopes found on trypomastigotes share homology with muscle cells.Immune system will mount response to both epitopes regardless if it is “self”. Leading to a production of Antibodies against muscles, including the heart (Cardiomyopathy-80%).

Treatment

Treatment options for Chagas’ disease are limited due to the poor efficacies and toxicities of the available drugs (Buckner, Wilson, White, & Voorhis, 1998). The main drug available for the treatment for Chagas’ disease is benznidazole, whose action eliminates T. cruzi parasites. This compound, however, has limited efficacy and a degree of high toxicity. Benznidazole is active only against the initial acute phase of the disease, although a recent large-scale, multicenter, international trial (BENEFIT project) indicated that treatment against chronic stages is an appropriate course of action, especially for patients with cardiovascular complications (Hall & Wilkinson, 2012).

Antiparasitic Treatment

Antiparasitic treatment is indicated for all cases of acute or reactivated Chagas disease and for chronic Trypanosoma cruzi infection in children up to age 18. Congenital infections are considered acute disease. Treatment is strongly recommended for adults up to 50 years old with chronic infection who do not already have advanced Chagas cardiomyopathy. For adults older than 50 years with chronic T. cruzi infection, the decision to treat with antiparasitic drugs should be individualized, weighing the potential benefits and risks for the patient. Physicians should consider factors such as the patient's age, clinical status, preference, and overall health(Buckner, Wilson, White, & Voorhis, 1998). The two drugs used to treat infection with Trypanosoma cruzi are nifurtimox and benznidazole. Benznidazole and nifurtimox are 100 percent effective in killing the parasite and curing the disease, but only if given soon after infection at the onset of the acute phase.For both drugs, side effects are fairly common, and tend to be more frequent and more severe with increasing age.

Common side effects of benznidazole treatment include:

- allergic dermatitis

- peripheral neuropathy

- anorexia and weight loss

- insomnia

The most common side effects of nifurtimox are:

- anorexia and weight loss

- polyneuropathy

- nausea

- vomiting

- headache

- dizziness or vertigo

Vaccination Challenges + Advantages

It is impossible to develop vaccines based on whole organisms (attenuated or otherwise). These vaccines provoke autoimmune disease due to homology in protiens. This leads to a result in which autoimmunity is achieved without ever having been in contact with a parasite.

An alternative approach for developing and testing new small molecular drug targets and candidates would be to develop and test a therapeutic vaccine, which could be administered as an immunotherapy either to individuals with chronic Chagas disease or those with indeterminate status who may go on to develop cardiomyopathy(Hall & Wilkinson, 2012). The advantages of a therapeutic Chagas disease vaccine compared with benznidazole alone (the current major competing product in clinical use) could include the following:

- Reductions in toxicities, thereby allowing its expanded use in indeterminate and determinate patients

- Higher efficacies at preventing cardiac complications

- Higher rates of seroreversion to T. cruzi antigens not contained in the vaccine

- Potential use in pregnancy to prevent congenital Chagas disease

Other Treatments

Azoles which were developed as antifungal drugs, are widely used clinically to treat mycotic infections. In fungi, azoles inhibit the cytochrome P-450 enzyme lanosterol 14ademethylase, causing the accumulation of 14a-methylsterols and the decreased production of ergosterol. Nitroimidazoles such as the metronidazole family of antibiotics are used to treat a range of microaerophilic/anaerobic bacterial and protozoal infections. (Hall & Wilkinson, 2012) Miconazole and econazole were the first of these inhibitors tested in T. cruzi and showed potent growth inhibition (Buckner, Wilson, White, & Voorhis, 1998). The finding that the azole-resistant parasites were not resistant to benznidazole indicates selectivity in the drug resistance mechanism (Buckner, Wilson, White, & Voorhis, 1998).

Prevention

If you live in a high-risk area for Chagas disease, these steps can help you prevent infection:

- Avoid sleeping in a mud, thatch or adobe house. These types of residences are more likely to harbor triatomine bugs.

- Use insecticide-soaked netting over your bed when sleeping in thatch, mud or adobe houses.

- Use insecticides to remove insects from your residence.

- Use insect repellent on exposed skin.

References

- Buckner, F. S., Wilson, A. J., White, T. C., & Voorhis, W. C. (1998). Induction of Resistance to Azole

- Drugs in Trypanosoma cruzi. Antimicrobial Agents And Chemotherapy, 42(12), 3245–3250.

- Davies, C., Cardozo, R. M., Negrette, O. S., Mora, M. C., Chung, M. C., Basombrio, M. A. (2010).

- Hydroxymethylnitrofurazone Is Active in a Murine Model of Chagas' Disease. Antiomicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (9). 3584-3589. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01451-09.

- Dumonteil E, Nouvellet P, Rosecrans K, Ramirez-Sierra MJ, Gamboa-León R, et al. (2013) Eco-Bio-Social Determinants for House Infestation by Non-domiciliatedTriatoma dimidiata in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7(9): e2466. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002466

- Garcia, S., Ramos, C. O., Senra, J. F., Vilas-Boas, F., Rodrigues, M. M., Campos-de-Carvalho, A. C., . . . Soares, M. B. (2005). Treatment with Benznidazole during the Chronic Phase of Experimental Chagas’ Disease Decreases Cardiac Alterations. Antimicrobial Agents And Chemotherapy, 49(4), 1521–1528.

- Hall, B. S., & Wilkinson, S. R. (2012). Activation of Benznidazole by Trypanosomal Type I Nitroreductases Results in Glyoxal Formation. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 56(1), 115-123.

- Henderson, G. B., Ulrich, P., Fairlamb, A.H., Rosenberg, I., Pereira, M., Sela, M., Cerami, A. (1988). “Subversive” substrates for the enzyme trypanothione disulfide reductase: Alternative approach to chemotherapy of Chagas disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 85(15). 5574-5578.

- Higuchi, M. d., Benvenuti, L. A., Reis, M. M., & Metzger, M. (2003). Pathophysiology Of The Heart In Chagas' Disease: Current Status And New Developments. Cardiovascular Research,60(1), 96-107.

- Hotez PJ, Bottazzi ME, Franco-Paredes C, Ault SK, Periago MR (2008) The Neglected Tropical Diseases of Latin America and the Caribbean: A Review of Disease Burden and Distribution and a Roadmap for Control and Elimination. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2(9): e300. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0000300

- Laranja, F. S., Dias, E., Nobrega, G., Miranda. (1956). A. Chagas' disease: A clinical, epidemiologic, and pathologic study. Circulation. 14. 1035-1060. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.14.6.1035

- Mejia, A. M., Hall, B. S., Taylor, M. C., Gómez-Palacio, A., Wilkinson, S. R., Triana-Chávez, O., & Kelly, J. M. (2012). Benznidazole-Resistance in Trypanosoma cruzi Is a Readily Acquired Trait That Can Arise Independently in a Single Population. Journal of Infectious Diseases, 206(2), 220-228.

- Moncayo, A., Antonio C. S. (2009). Current epidemiological trends for Chagas disease in Latin America and future challenges in epidemiology, surveillance and health policy. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 104. 17-30. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000900005