Table of Contents

PRESENTATION SLIDES

INTRODUCTION

Scabies is caused by the parasitic arthropod Sarcoptes scabiei, also known as the itch mite. The name S. scabiei comes from the Greek word “sarx” (flesh) and “koptein” (to cut) and the Latin word “scabere” (to scratch) (Hengge et al., 2006). S. scabiei are so small that they cannot be seen by the naked eye. While the disease has existed for thousands of years, the organism that causes the disease was first discovered using a light microscope in the 1600s by Italian biologists Giovan Cosimo Bonomo and Diacinto Cestoni (Montesu & Cottoni, 1991).

S. scabiei var. hominis are human specific, and as such, cannot affect or be passed on by animals (Arlian et al., 1984). While scabies can occur in other animals, the mite that causes the condition is a different subspecies from those that affect humans. For instance, the subspecies S. scabiei var. canis affects dogs, and the subspecies S. scabiei var. suis affects pigs (Arlian & Morgan, 2017).

HISTORY

The presence of scabies dates back to as late as 400 B.C. based on archaeological evidence found in the Middle East (Roncalli, 1987). However, the earliest written reference to the disease dates back to 1200 B.C. in the biblical book Leviticus (Roncalli, 1987).

The root cause of the itch was first discovered by G.C. Bonomo and D. Cestoni in 1687, who at the time named the mite Acarus scabiei (Roncalli, 1987). Upon discovering the mite, the researchers used low magnification microscopes to evaluate the identity of this bug-like moving organism. They saw that it appeared to gnaw and eat, and created “streets” on the surface of the skin. Additionally, they observed the organism hatched out of an egg (Roncalli, 1987). What was remarkable about this discovery was that it not only established a reason for what initiates scabies, but was also the first time in the history of medicine that a definitive cause was linked to a human disease (Roncalli, 1987).

EPIDEMIOLOGY

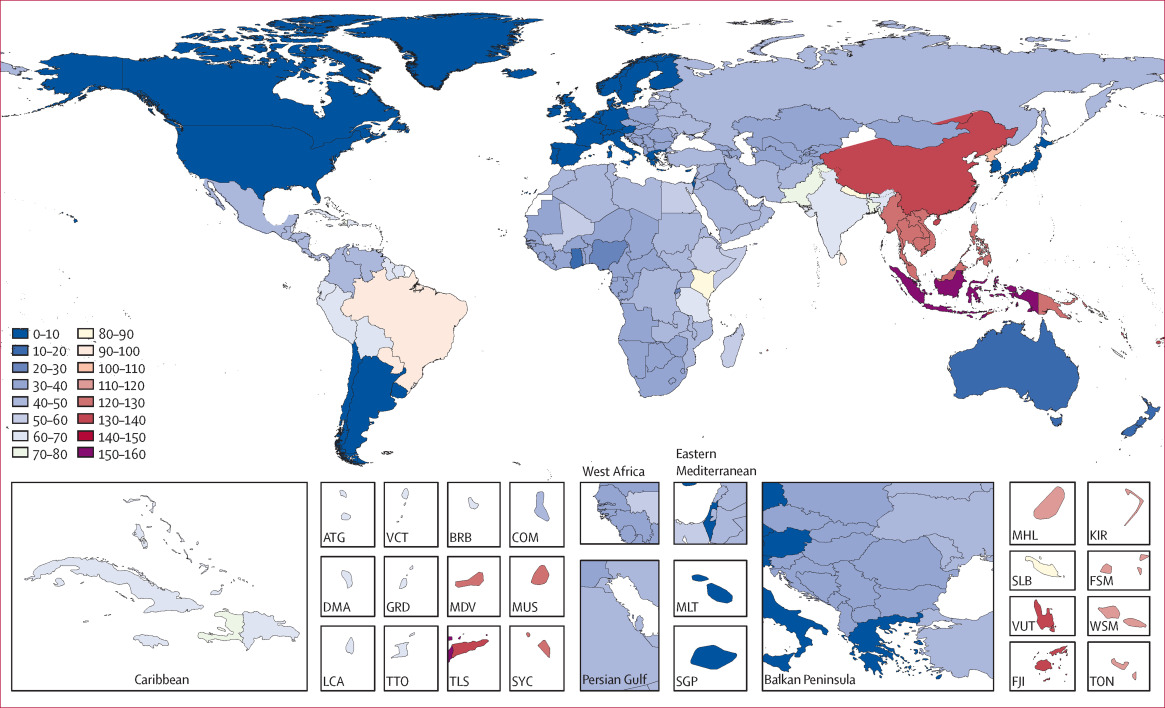

Scabies is commonly found across the world and affects all age groups. However, it is a major health issue in the developing world where treatment is sometimes neglected or difficult to attain. Various statistics on the prevalence of scabies worldwide have been reported.

In developed countries, scabies is often unheard of as it is a disease that affects a minimal percentage of the population. Based on a review of data collected over 9 years from 1997 to 2005 in the United Kingdom, it was estimated that scabies affected only 2.81 per 1000 women and 2.27 per 1000 men (Razon & Weidman-Evans, 2017).

Countries with social disruption and overcrowding have been associated with an increased risk of scabies acquisition. As a result, there is a high prevalence of scabies in developing and third world countries. A recent study performed in North India demonstrated that scabies accounted for 4.4% of the skin diseases present in 1275 household members assessed within a community. In Chile, the reported prevalence of scabies is 1% to 5% of the population (Romani et al, 2015). A study of patients at a Cairo university hospital reported scabies as the most common presenting dermatosis, constituting 9.3% of all cases (Karimkhani et al, 2015). Another study investigating 1337 boys in a Saudi Arabian school found skin diseases in 27% of the children, with scabies identified as a common dermatosis with a higher incidence than other infectious dermatoses in rural schools (Strong & Johnstone, 2011). Furthermore, a Nigerian study found 13.5% of patients in a children’s hospital had scabies. In a survey of 120 children in a welfare home in Malaysia, 46% of 10 to 12-year-olds had scabies (Strong & Johnstone, 2011).

SIGNS & SYMPTOMS

The scabies mite excavates superficial burrows through the epidermis resulting in itching and bumpy red rashes (CDC, 2018). Symptoms are caused by an inflammatory immune response due to the presence of the mites, in addition to their eggs and feces (CDC, 2018). Thus, a virgin infection features a 4 to 6 week incubation period prior to the onset of any symptoms, since it takes time for the immune system to recognize the intrusion (CDC, 2018). Subsequent infections from S. scabiei. significantly reduce the time for the onset of symptoms from weeks to a few days (CDC, 2018). It is important to note however, that an individual can be infectious before experiencing symptoms (CDC, 2018).

Itching & Rashes

Scabies can develop anywhere on the skin but tends to occur most commonly in acral areas and crevices of the body, including the finger webs, hands, wrists, feet, buttocks, and penis (Chouela et al., 2002). The symptoms get worse at elevated temperatures and at night since the mites are more active when the body is sedentary (Hay, 2009). Persistent itching can damage the skin and increase the risk of secondary bacterial infections (CDC, 2018). Rashes are the result of the mites’ burrowing through the skin. The burrows are linear or zigzag in appearance and lead to the presentation of scattered red papules on the skin (CDC, 2018). They are typically not found in non-acral regions of the body such as the skin of the head, however, such areas can be infected by the mite in individuals with a weak immune system such as infants and the elderly (Hay, 2009).

DIAGNOSIS

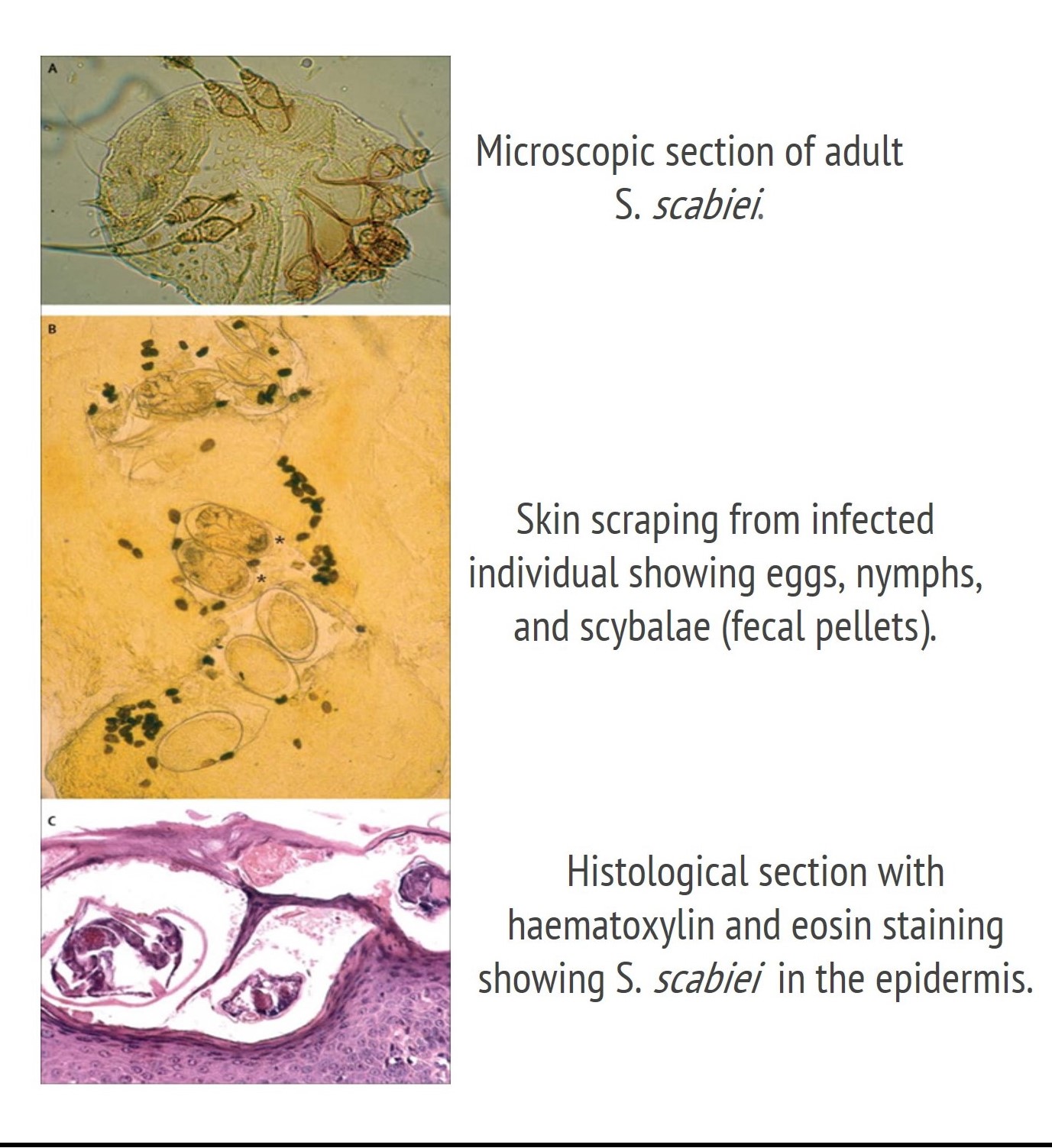

Diagnosis for scabies involves finding the mites, their eggs, or faecal pellets (Andrews et al., 2009). This can be achieved by examining a treated skin sample under a microscope or by using dermatoscopy to inspect the skin (Hay, 2009). Discovery of mites, their eggs, or faecal pellets during an inspection, directly confirms that an individual has scabies. Alternatively, scabies burrows can be found by treating the infected skin area with a tetracycline solution and viewing the skin under a Wood light (Andrews et al., 2009). The light will allow the tetracycline within the burrows to fluoresce a greenish colour. Deciphering the results can be difficult due to the scarcity of burrows and potentially skewed results caused by damaged skin but can still lead to an effective diagnosis of scabies (Andrews et al., 2009).

CAUSES

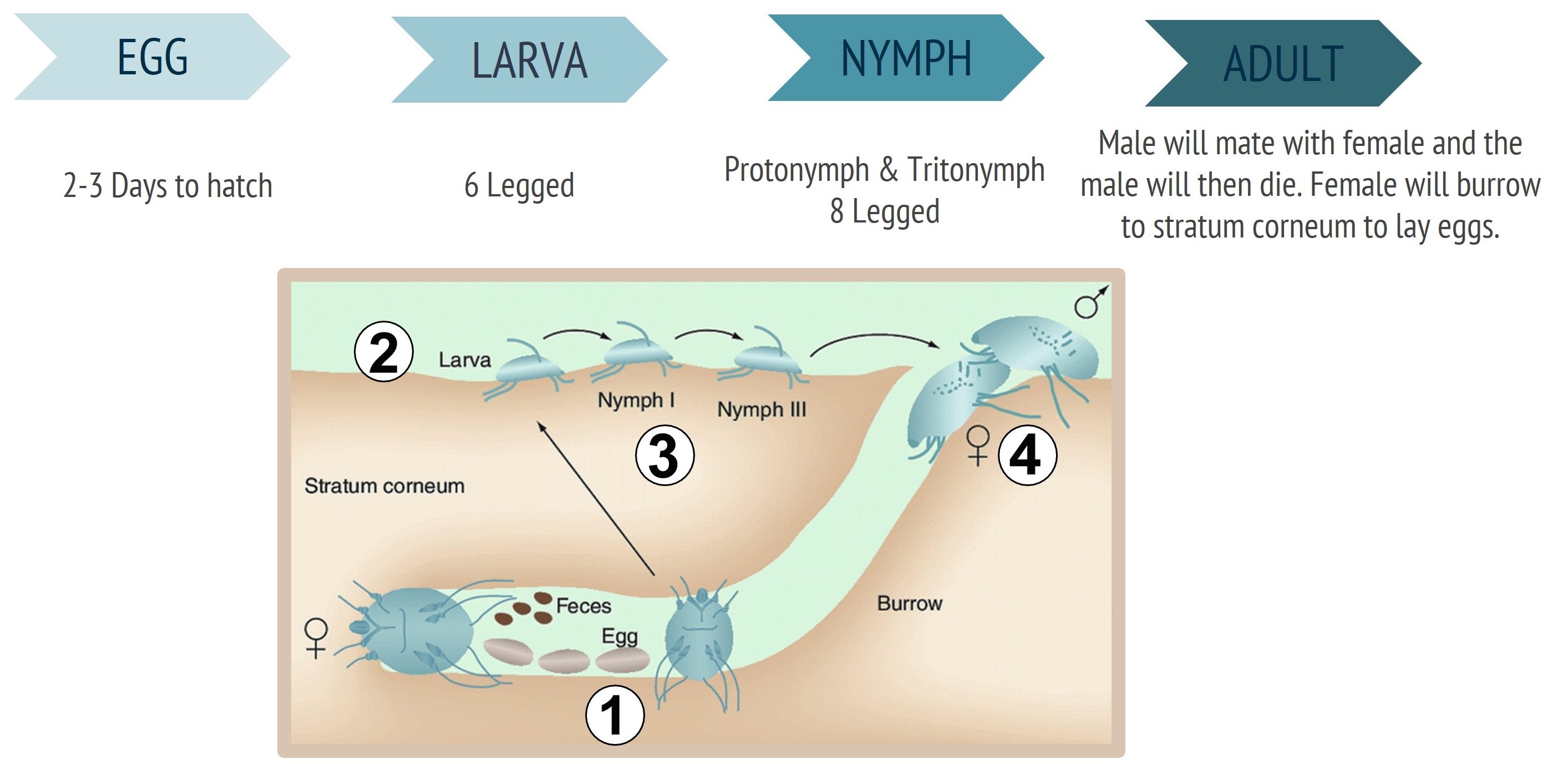

The itchy symptoms and scars are a result of the mites’ feeding and burrowing through the skin. After mating with a male mite, the female will dig through the superficial layer of the skin until it reaches the stratum corneum to lay its eggs (Burgess, 2003). Females produce about 40 to 50 eggs over their life (Arlian & Morgan, 2017). The eggs take about 2 to 3 days to hatch (Burgess, 2003). Depending on the seriousness of the condition, an individual with the disease can have anywhere from ten to millions of mites (e.g., in cases of crusted scabies) feeding on their skin (Johnston & Sladden, 2005).

Life Cycle of the Mite

S. scabiei goes through 4 life cycle stages: egg, larva, nymph (protonymph and tritonymph) and adult (Arlian & Morgan, 2017). After the female lays her eggs in the stratum corneum of the skin, the eggs will take a few days to hatch (Hengge et al., 2006). Afterwards, the nascent six-legged larvae begin feeding on the skin and digging small pockets called moulting pouches (Hengge et al., 2006). After 3 to 4 days, the six-legged larvae transform into eight-legged protonymphs, and then into a tritonymph 2 to 5 days later (Hengge et al., 2006). Finally, they molt into either males or females 4 to 7 days later (Arlian & Morgan, 2017). Once reaching the adult stage, the mites can live on their host for about 1 to 2 months (McClain & Goldenberg, 2009). The adult female mite will then create a burrow to hide within. The male will enter this burrow to mate with the female. After mating the male will die and the female will continue digging down to the stratum corneum, never returning to the surface of the skin again (Burgess, 2003). However, it should be noted that there is considerable variation in reported durations of the mites’ life cycle in humans due to difficulty in observing their development on the skin in vivo and the natural genetic differences and environmental factors between the mites (Arlian & Morgan, 2017).

Figure 4: The 4 life cycles stages of S. scabiei. 1) The female mite creates a burrow through the skin and lays her eggs. 2) Larvae hatch from the eggs, exit the burrows and feed on the surface of the skin. 3) Larvae then develop into nymphs (protonymphs and then tritonymphs). 4) Soon afterwards they molt into male or female adults. Male mites will die after intercourse with a female mite. (Retrieved from: Mumcuoglu, Gilead, & Ingber, 2009)

Method of Transmission

Scabies is quite contagious as typical transmission of the mite from one person to another is accomplished via skin-to-skin contact, including sexual intercourse (Burgess, 2003). Since the mites reside on and within the outer layer of the skin, they can easily crawl to new hosts leading to infestation. They can also be transferred from personal items used by individuals with the disease, such as clothes, furniture, toys, and bedding (Arlian & Morgan, 2017). The mites can survive away from a host’s skin for approximately 24 to 48 hours (McCarthy, 2004).

Crusted Scabies

Crusted scabies, also known as Norwegian scabies, is a severe chronic form of scabies that is characterized by thick crusts of skin that can contain millions of scabies mites and eggs. (Walton et al., 2008) The condition is often found in individuals with a weak immune system (Karthikeyan, 2009). As a result, these individuals are often unable to create an immune response to control the mites’ replication. In addition, it creates a fertile environment with higher hatch rates allowing the scabies infection to spread more efficiently (CDC, 2018). If left untreated, the individual can die from the condition (Karthikeyan, 2009). Individuals infected with this form of scabies can host up to two million mites, significantly increasing the risk of transmission through contact (CDC, 2018). Although the infection features exponentially higher populations of mites, virulence in comparison to typical scabies remains the same (CDC, 2018). Individuals with the condition will have skin disfigurement as a result of crusting, rotting flesh and will be in immense pain (Karthikeyan, 2009). Additionally, the thick crusts of skin protect the mites and obstruct topical skin treatments (CDC, 2018).

In 2005, researchers looked at 78 patients with crusted scabies (Roberts et al., 2005). This was the largest reported case series of crusted scabies. They found that individuals had identifiable immunosuppressive risk factors such as elevated IgE levels and eosinophilia in 96% and 58% of patients, respectively. A major risk factor for crusted scabies is a past history of leprosy, and this was indeed found in 17% of the individuals in this study. Susceptibility to lepromatous leprosy has been shown to relate to a Th2 type of T helper immune response. This group of patients may, therefore, represent natural Th2 type responders rendering them susceptible to both leprosy and crusted scabies.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The itchiness and rashes are the result of an immune response initiated by secretions from the mite. After the mite burrows through the skin, an inflammatory response initiates immune response molecules such as eosinophils, lymphocytes and histiocytes (Heukelbach & Feldmeier, 2006). T-cells are lymphocytes that participate in an immune response. There are 2 types of T-cells that are initiated with either the normal or crusted scabies. In normal scabies (i.e. non-crusted scabies) CD4 + T-cells are the more dominant, while in crusted scabies the CD8 + T-cells are more prominent (Walton et al., 2004). Hypersensitivity reactions are a group of conditions in which the immune system, which normally serves a protective role, has a harmful effect. It takes 2 to 6 weeks before itching occurs in a person not previously exposed to scabies. This latency period is due to a type IV hypersensitivity reaction against the mite and its antigens (Henge et al., 2006). Type IV delayed hypersensitivity is called cell-mediated hypersensitivity and involves the CD4+ T cells (Henge et al., 2006). In the presence of antigens, the CD4+ T cells release mediators such as cytokines, which activate cytotoxic T-cells that can cause accumulation of fluid containing proteins that lead to the formation of papules (Walton et al., 2004). The T cells help with the immune response by secreting cytokines which recruit and activate other lymphocytes. Currently, there are not many studies done in vitro for T-cell response to S. scabiei antigens (Walton et al., 2004). There is also not much research done on the biology of the mite and its relationship with its host due to the absence of animal models (Heukelbach & Feldmeier, 2006). The immune response does not eliminate all mites from the skin surface but does help limit further multiplication of mites (Cabrera et al., 1993).

MANAGEMENT & TREATMENT

Scabies can be prevented by avoiding direct skin-to-skin contact with an infected person or their personal items. If an individual has had prolonged skin-to-skin contact with an infected person, they should seek treatment immediately even if they do not exhibit any signs or symptoms in order to prevent the disease from taking form (CDC, 2018). For control measures, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend laundering the items of an infected person at a temperature of about 60°C (140°F) and drying them in a hot dryer (CDC, 2018). For items that cannot be laundered or dry-cleaned, they should be isolated in a plastic bag for at least 72 hours since the mites are incapable of surviving more than 2 to 3 day away from a hosts’ skin. A person with crusted scabies should be treated quickly, along with anyone they have had close contact with to prevent the disease from taking on a more serious form and to prevent its spread or reemergence. Rooms used by infected individuals should also be thoroughly cleaned and vacuumed. Institutional outbreaks of scabies are challenging to control and treat and require a rapid and aggressive response. Environmental disinfestation measures using pesticide sprays, powders, or fogs is unnecessary and discouraged (CDC, 2018).

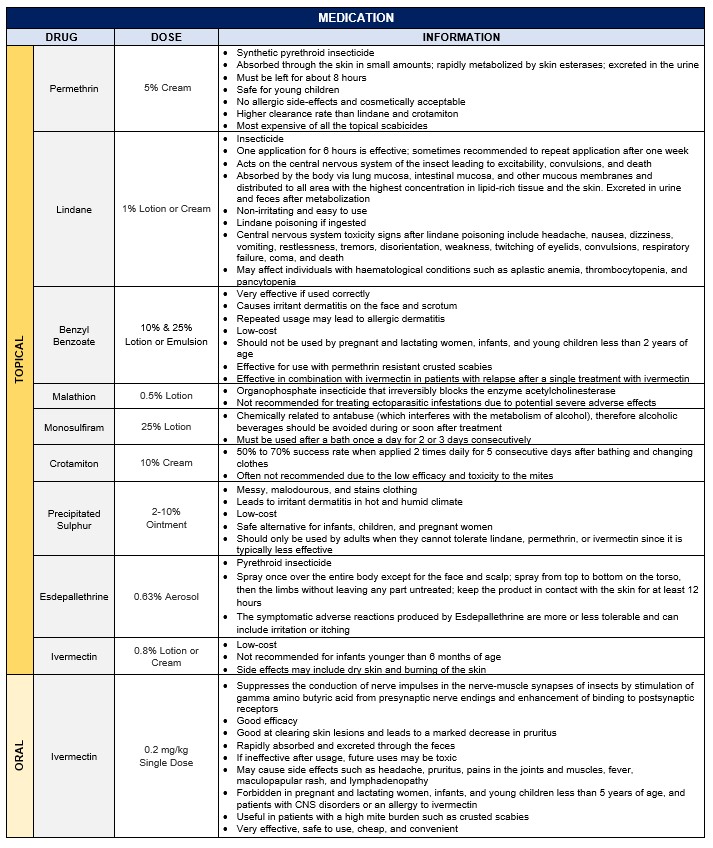

Medications used for treating scabies are called scabicides and are only available with a doctor’s prescription. Currently, no “over-the-counter” products have been tested or approved. The medication is generally applied topically or taken orally (CDC, 2018).

A topical treatment is applied to all skin regions from the neck down, as well as the head of infants or individuals who are bald (CDC, 2018). Before applying the medication, the skin should be clean, dry, and cool. The medicine should be left for the recommended amount of time (8 to 12 hours) for it to be effective and clean clothing should be worn (Karthikeyan, 2005). A second application may be required after 7 to 14 days. The doctor will also sometimes prescribe antihistamines, pramoxine lotions, and/or steroid creams to control the itching and antibiotics for infections (Karthikeyan, 2005). It is important to follow the doctor’s instructions carefully, since treating the skin more often than instructed can worsen the rash and itching. Itching may continue for several weeks after treatment even if all the mites and eggs are killed (Karthikeyan, 2005). Retreatment may be necessary if the symptoms persist for more than 2 to 4 weeks after the first treatment or new burrows or rashes appear (CDC, 2018). Treatment failures are uncommon but may occur due to inadequate application, resistance, or re-infestation. Pregnant and lactating women, infants, and young children less than 2 years of age should be treated for scabies only if the benefits exceed the risks and if instructed by a doctor (Karthikeyan, 2005).

The best drug of choice is Permethrin followed by Lindane and Benzyl Benzoate (Karthikeyan, 2005). Crusted scabies may require several treatments with scabicides and sometimes several different medications used sequentially. Ivermectin is now emerging as an effective oral drug that is safe to use for adults and can also treat crusted scabies (Karthikeyan, 2005). However, Lindane and Benzyl Benzoate still holds popularity in the developing world since Permethrin is expensive.

REFERENCES

Andrews, R. M., McCarthy, J., Carapetis, J. R., & Currie, B. J. (2009). Skin disorders, including pyoderma, scabies, and tinea infections. Pediatric Clinics, 56(6), 1421-1440. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.002

Arlian, L. G., & Morgan, M. S. (2017). A review of Sarcoptes scabiei: past, present and future. Parasites & vectors, 10(1), 297. doi: 10.1186/s13071-017-2234-1

Arlian, L. G., & Vyszenski-Moher, D. L. (1988). Life cycle of Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis. The journal of Parasitology, 427-430. doi: 10.2307/3282050

Arlian, L. G., Morgan, M. S., Vyszenskimoher, D. L., & Stemmer, B. L. (1994). Sarcoptes scabiei: the circulating antibody response and induced immunity to scabies. Experimental parasitology, 78(1), 37-50. doi: 10.1006/expr.1994.1004

Arlian, L. G., Runyan, R. A., Achar, S., & Estes, S. A. (1984). Survival and infectivity of Sarcoptes scabiei var. canis and var. hominis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 11(2), 210-215. doi: 10.1016/S0190-9622(84)70151-4

Bouvresse, S., & Chosidow, O. (2010). Scabies in healthcare settings. Current opinion in infectious diseases, 23(2), 111-118. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328336821b

Burgess, I. F. (2003). Understanding scabies. Parasitology, 74(3), 427-430. Retrieved from https://www.nursingtimes.net/Journals/2012/10/.../030218Understanding-scabies.pdf

Cabrera, R., Agar, A., & Dahl, M. V. (1993, March). The immunology of scabies. In Seminars in dermatology (Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 15-21). doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2009.09.002

Chouela, E., Abeldaño, A., Pellerano, G., & Hernández, M. I. (2002). Diagnosis and treatment of scabies. American journal of clinical dermatology, 3(1), 9-18. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200203010-00002

CDC. (2018, October 31). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention-Scabies. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/index.html

Dahl, M. V. (1983). The immunology of scabies. Annals of allergy, 51(6), 560-566. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6419647

Esdepallethrine. (2016) Drug Information System. Retreived from: http://www.druginfosys.com/drug.aspx?drugcode=2287&type=1

Hay, R. J. (2009). Scabies and pyodermas–diagnosis and treatment. Dermatologic therapy, 22(6), 466-474. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01270.x

Hengge, U. R., Currie, B. J., Jäger, G., Lupi, O., & Schwartz, R. A. (2006). Scabies: a ubiquitous neglected skin disease. The Lancet infectious diseases, 6(12), 769-779. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70654-5

Heukelbach, J., & Feldmeier, H. (2006). Scabies. The Lancet, 367(9524), 1767-1774. doi: doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68772-2

Hicks, M. I., & Elston, D. M. (2009). Scabies. Dermatologic therapy, 22(4), 279-292. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01243.x

Ivermectin Topical: MedlinePlus Drug Information. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a613011.html

Jailman, D. (2018). Scabies Slideshow: Symptoms, Cause, and Treatments. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/skin-problems-and-treatments/ss/slideshow-scabies-overview

Johnston, G., & Sladden, M. (2005). Scabies: diagnosis and treatment. Bmj, 331(7517), 619-622. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7517.619

Karthikeyan, K. (2005). Treatment of scabies: newer perspectives. Postgraduate medical journal, 81(951), 7-11. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.018390

Karthikeyan, K. (2009). Crusted scabies. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprology, 75(4), 340. Retrieved from: http://www.ijdvl.com/text.asp?2009/75/4/340/53128

Karimkhani, C., Colombara, D. V., Drucker, A. M., Norton, S. A., Hay, R., Engelman, D., … & Dellavalle, R. P. (2017). The global burden of scabies: a cross-sectional analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. The Lancet infectious diseases, 17(12), 1247-1254. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30483-8

McCarthy, J. S., Kemp, D. J., Walton, S. F., & Currie, B. J. (2004). Scabies: more than just an irritation. Postgraduate medical journal, 80(945), 382-387. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2003.014563

McClain, D., Dana, A. N., & Goldenberg, G. (2009). Mite infestations. Dermatologic therapy, 22(4), 327-346. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2009.01245.x

Montesu, M. A., & Cottoni, F. (1991). GC Bonomo and D. Cestoni. Discoverers of the parasitic origin of scabies. Retrieved from: https://europepmc.org/abstract/med/1928627

Mumcuoglu, K. Y., Gilead, L., & Ingber, A. (2009). New insights in pediculosis and scabies. Expert Review of Dermatology, 4(3), 285-302. doi: 10.1586/edm.09.18

Prevention, C.-C. for D. C. and. (2010). CDC - Scabies - Disease. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/disease.html

Prevention, C.C. for D. C. and. (2010). CDC - Scabies - Epidemiology & Risk Factors. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/epi.html

Prevention, C.-C. for D. C. and. (2018). CDC - Scabies - Treatment. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/scabies/treatment.html

Razon, F. M., & Weidman-Evans, E. (2017). Insight into scabies. Journal of the American Academy of PAs, 30(2), 1-3. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000511790.29560.a2

Roberts, L. J., Huffam, S. E., Walton, S. F., & Currie, B. J. (2005). Crusted scabies: clinical and immunological findings in seventy-eight patients and a review of the literature. Journal of Infection, 50(5), 375-381. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.08.033

Roncalli, R. A. (1987). The history of scabies in veterinary and human medicine from biblical to modern times. Veterinary Parasitology, 25(2), 193–198. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(87)90104-X

Romani, L., Steer, A. C., Whitfeld, M. J., & Kaldor, J. M. (2015). Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 3099(15), 1–8. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00132-2

Strong, M., & Johnstone, P. (2011). Cochrane review: interventions for treating scabies. Evidence‐Based Child Health: A Cochrane Review Journal, 6(6), 1790-1862. doi: 10.1002/ebch.861

Walton, S. F. (2010). The immunology of susceptibility and resistance to scabies. Parasite immunology, 32(8), 532-540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.2010.01218.x

Walton, S. F., Beroukas, D., Roberts‐Thomson, P., & Currie, B. J. (2008). New insights into disease pathogenesis in crusted (Norwegian) scabies: the skin immune response in crusted scabies. British Journal of Dermatology, 158(6), 1247-1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08541.x